Illustration on the front page:

Stutterheim, W. F., Pictoral history of civilization in Java. Translated by Mrs. A. c. de Winter-Keen, The Java-Institute and G. Kolff & Co., Weltevreden, 1926

At five o’clock in the afternoon, on the 27th of May (in 1921), De Melchior Treub of the Dutch K.P.M. Company left the pier of Singapore gently.

Many passengers on the deck were bidding farewell to the people on the quay. There was a young woman who seemed to be missing someone and putting her handkerchief to her eyes. With nobody to send me off, I was a little lonely surrounded by all those people but I felt, in a way, that it was easy to be unbothered by anyone.

The boat sailed along the coast of Singapore where palm-tree woods continued down to the shore. After passing the strait between the Batam and Bintan Islands, she proceeded on the tropical sea as if she were sliding on an oil-covered surface. It was quite comfortable for passengers that the white-painted 3,000-ton vessel built as a purely passenger-boat, had a wide lounge on the deck and well-furnished cabins, and every part of the ship was kept tidy by the cleanliness-loving Dutch crew. What made us wonder and indeed interested us were the jongos, or servant boys. All of these crew members were Javanese who tied a folded batik tidily around their heads like a cap and wore a sarong, and went bare-footed according to their own customs. It was strange to see them sitting cross-legged either on the deck or in the corridors whenever they had no work.

The majority of the passengers were Dutch. A considerable number of half-castes on board seemed to me as a shadowy part of the colonial area. Japanese passengers besides the three of us were Mr. Irie whom we met on the Kaga-Maru[1], and Mr. Tani, of the Asahi Newspaper, who had happened to be on De Melchior Treub.

The skyline of clouds towering on the distant horizon was coloured by the evening sun as if they were burning. The sea of the south is calm and lonesome, whereas the sea in the north is wild and bleak.

In the tropical zone, there is neither dawn nor dusk. The darkness of the night continues onto daylight and changes within a matter of fifteen minutes. As soon as the sun sets under the wave, the darkness arrives from the east and stars sparkle there, while the other half of the sky is still light.

I shall be a man on the Southern Hemisphere tonight, by crossing the equator. It is a bit lonesome to be separated thousands of miles away from the north. Standing on the deck, I am thinking of the people there by looking above at the bright Southern-Cross.

28th of May. Having crossed the equator during the night, the first day in the Southern Hemisphere opened quietly. The sea of the tropical zone was calm and a line of white wake was extending endlessly from the stern of the sliding boat. In this distant sea of the south, where the sun was seen in the north, I felt as if the line of wake was a narrow string which ties the relationship between the north and the south.

When I climbed up to the deck after breakfast, the boat was taking a course with Bangka Island on her port-side. On the north tip of the island, stood a lonely white light-house, casting a contrast to the marine-blue sea. This was the famous Strait of Bangka, and Sumatra was seen low on the horizon in the starboard side, over the distant hazy waves. Despite the breeze blowing over the sea, the heat at midday on the equator was intolerably intense, so that everybody was lying on a rattan bench and gasping for breath without wiping away the oozing sweat.

The chief-steward of the boat was an extremely active Dutchman who was working busily all day long, as if he had not a single-minute to rest. When the restaurant opened, he conducted slothful jongos to their posts and walked through the tables so that the guests would suffer no inconvenience. As soon as meals finished, he came up to the lounge to speak to guests in order to take care of their luggage, and give advice for money-changing and to do everything with a fine command of English, French, Dutch and Malay. If there were one moment he would stop, it would be the occasion when the boat was stranded. When he slept, he would be dreaming a dream of work.

An interesting thing I found on this boat was that the fish dishes were served last at dinner, in the Dutch manner. It made me feel as if I were following the menu in reverse order. Another thing was the Dutch-wife on the bed, a three-foot-long, pillow-shaped object used like a Chinese bamboo-lady to keep one’s stomach warm. It will not look attractive at all that one is holding it firmly to prevent a stomach-ache while sleeping.

On the 29th of May, the boat lay slowly alongside the pier at Tandjoeng Priok. Unlike in Singapore, there were no Chinese couriers nor black klings[2] and the only people there were languid-looking Javanese wearing colourful batik and white-dressed Dutch men and women.

It was heartening that Mr. Matsumoto, the Consul, Mr. Tahara, of Mitsui & Co., and Mr. Tsukuda, of Java Nippō[3] came to meet me. Since I had a return ticket, I was not charged the 25-roepiah immigration tax and passed customs without hindrance. So, we took a car immediately to Weltevreden.

Batavia, as it is called today, is the collective name of four independent cities, Tandjoeng Priok, Batavia, Weltevreden and Meester-Cornelis[4]. The old Batavia, formerly called Djakatra, is the home-land of the potato which I was fed every day and evening on the boat.

The name of ‘Djakatra’ is familiar to Japanese, reminding us of Jagatara-Bumi. When Christianity was banned once at the time of the Kan-ei Era in the 17th century, there was a girl called Oharu among the Christians who were expelled from Nagasaki. It was a letter she sent, by courtesy of a Dutch kabitan[5], to her relative in Japan to request the seeds of Japanese plants to console her homesickness[6]. I thought of the girl who had ended her life in this foreign land three hundred years ago.

The car ran like an arrow along the side of canals for a distance of six miles from Tandjoeng Priok to Weltevreden. There were goats loitering around the roadsides and white swans floating on the canal. Although it was not very broad, Batavia is a city of shining green-shades, designed by the Dutch who have a special talent for civil engineering, where smart white-painted houses are placed to match the environment. The canals were extended into the city-area, where Javanese men and women were having their mandi (m. bath or bathing) and washing clothes in the turbid water. I could not understand their sense in washing and cleaning things in such dirty water.

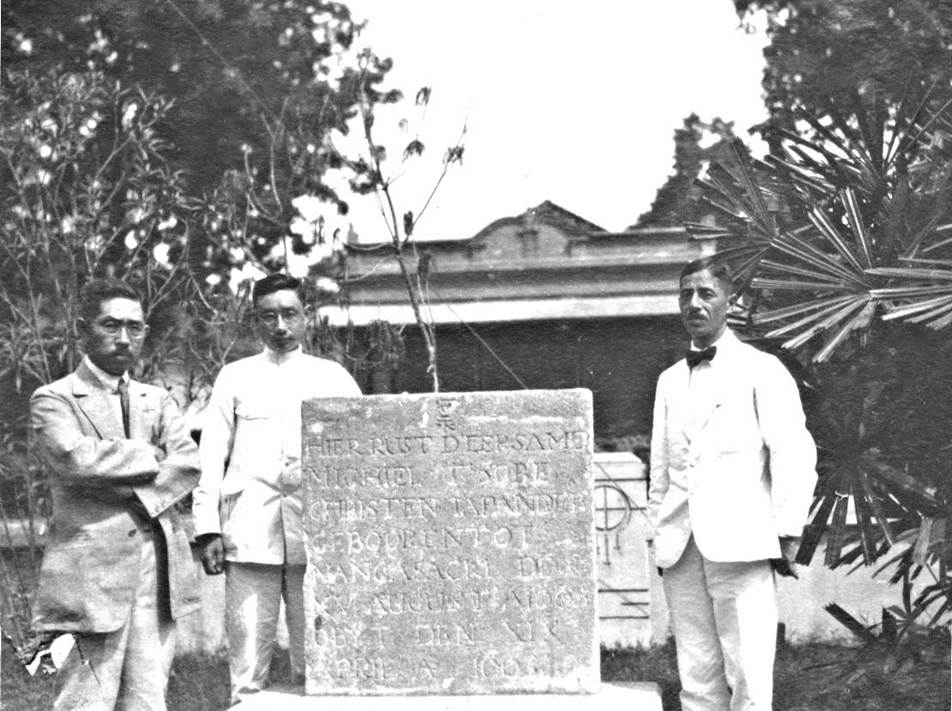

I was served a Japanese meal in the Consulate. There was a grave in front of the Consulate. According to the inscription, it was the tomb of a Japanese man, named “Michiel T. Sobe, born in Nagasaki in the 10th year of Keichō Era (1605) and died here in the 3rd year of Kanbun Era (1663)[7]”. Judging from his age, he was supposed to be one of those who led a resentful life in this land deported from Nagasaki with Oharu, the sender of Jagatara-bumi.

The tomb stone of Michiel Tf Sobe in the Japanese Consul

(Appended from the author’s private album)

I decided to go to Buitenzorg at once, putting off the sightseeing of Batavia, as I was scheduled to return here later. Guided by Mr. Tahara, of Mitsui & Co., the car ran the distance of 30 miles straight from Weltevreden, passing through Meester-Cornelis.

The car flew like an arrow on the surface of the road which was as smooth as a whetstone. The land around there was either sugar-cane fields or paddy rice-fields. The scenery was similar to the countryside in Japan, but to us who tended to think that harvesting was once a year in autumn, it felt strange that girls in colourful batik dresses were planting the seedlings of rice in one field and other people were collecting ripened, hanging ears of the same plant in another. It was however common in this

country of ever-lasting summer.

There were a number of buffaloes in the paddy fields which were looking at the speeding cars. Farmhouses surrounded by hedges, cocks and hens clucking at the traffic and children looking at us with wondering eyes in villages did not give me an impression of being in a foreign country, although the plants were quite different to ours.

The car covered the thirty miles in one hour and entered the city area of Buitenzorg. It was another town of tree-shades in which smart white Dutch houses stood surrounded by flower gardens. The town offered the fresh and quiet atmosphere of a southern country.

The town, which was formerly a mere countryside village called Bogor, was renamed Buitenzorg, or ‘care-free village’, in 1745[8], when the Governor-General van Imhoff built an Official Residence away from humid and unhealthy Batavia[9]. What has made the place more famous over time is the Great Botanical Garden, measuring more than 65 hectares, designed by Dr. Reinwardt[10],[11] and established in 1817. Ever since Dr. Melchior Treub[12] was appointed the director in 1880, the botanical garden was made by his efforts into the world’s best research centre for tropical botanical studies with fully equipped laboratories[13].

It was a great satisfaction to me, a person engaged in a part of botanical science, to be able to be in this special place where botanists of the world

sincerely wish to visit at least once, just as pilgrims desire to go to holy lands.

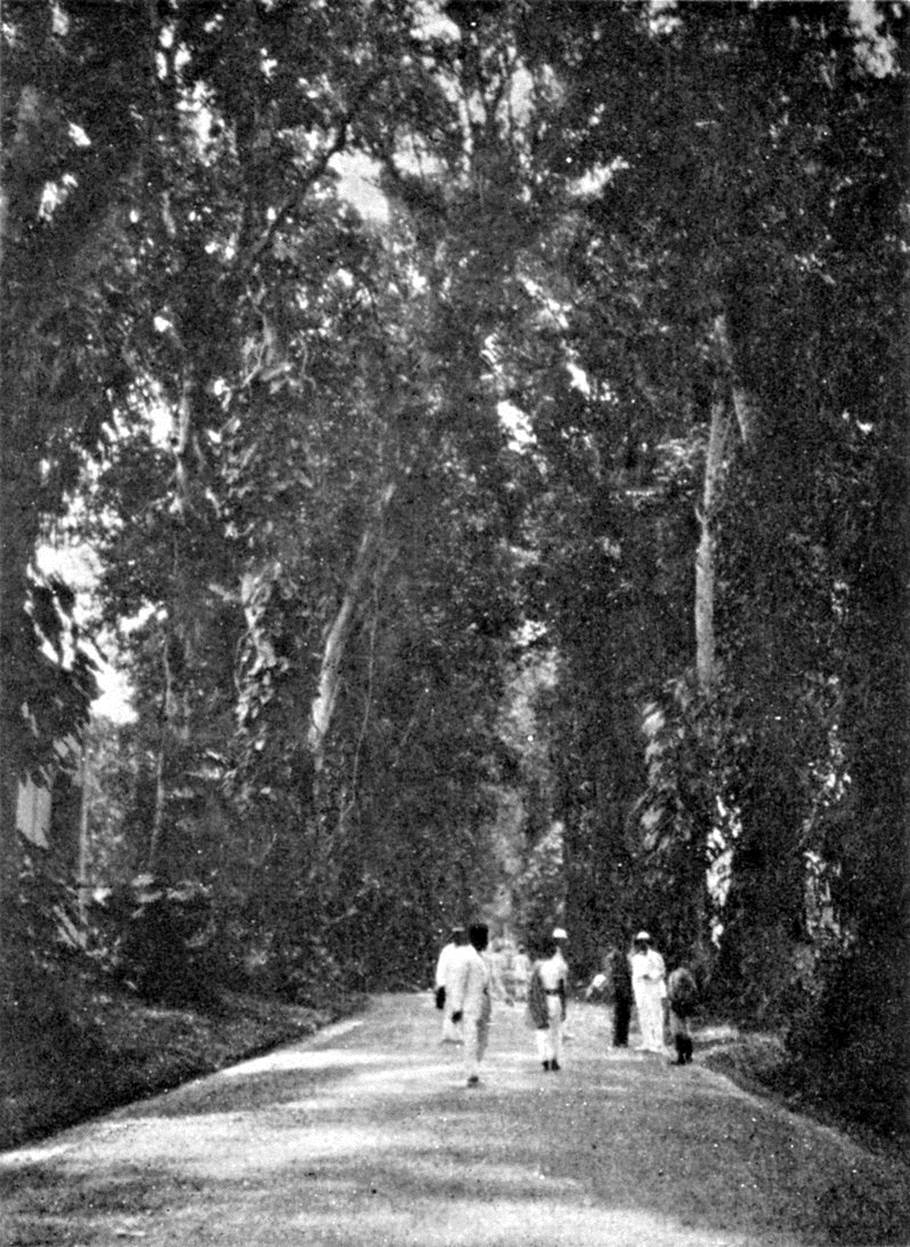

As soon as I put my luggage in the Hotel Bellevue which had been reserved as the night’s accommodation, I went to the Botanical Garden. During this botanical pilgrimage, what was surprising at first on entering the gate was the row of canary-trees stretching for several hundred metres into the distance. On the huge trees of 70 or 80 to 100 feet tall that cast a dark shade in the daytime, were vines of the plant of Arisaema serratum family, climbing up helically with leaves as big as those of taros[14].

The entrance of Buitenzorg Botanical Garden

A bare-footed, shabby child came to me to sell jewel beetles. With my poor Malay, I asked,

“Berapa harga ini? (How much is it?)”

“Sepoeloeh roepiah ini. (It is ten guldens[15].)”,

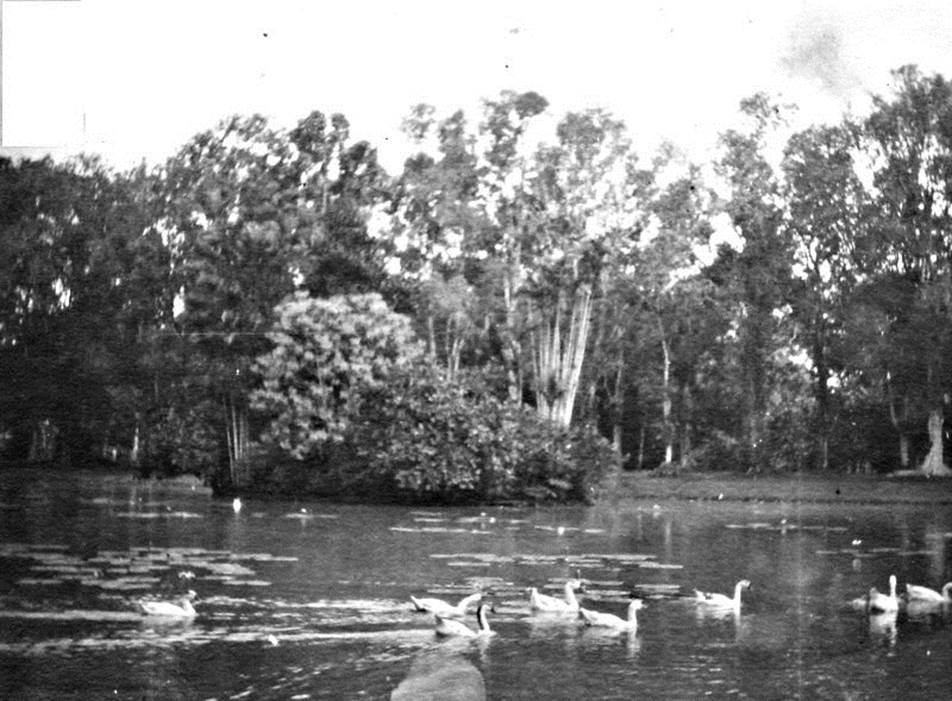

he replied. I was daunted by the extravagant price but they were so beautiful that I eventually bought three pieces after haggling for one gulden for all. When I walked along the avenue, a lake appeared between the trees. There was nobody around there. It was quiet and surrounded by the dark, thick vegetation of the woods. I felt as if I were at a lake-side hidden deep in a mountain rather than in a botanical garden. On the surface of the water, big leaves of giant water-lilies, measuring six feet in diameter and having a turned-up edge similar to that of a tray were floating on the surface of the water, and white swans were sliding peacefully, drawing ripples behind them. There was an island in the middle of the lake on which lipstick-palms[16] grew, and the flaming red of the sheaths of the leaves was impressive in contrast with the dark colour of the surroundings. A little further from the lake, standing in the middle of a vast green turf was of the Governor-General’s residence, a spotless white, magnificent marble-built mansion, having the forest of the botanical garden in the back. In front of the mansion, there was an umbrella-shaped tree, the name of which I did not recognise[17]. The tree, stretching its branches to cover the sky completely and casting a shadow of a width of more than ten thousand square metres was so big that it reminded me of a mythical tree in a legend. I read once that, in the era of Emperor Nintoku, there was a huge camphor tree on the west side of theTonoki River, the shadow of which reached Awaji Island under the morning sun and exceeded Mt. Takayasu in Kawachi in the afternoon[18]. There were deer under the tree in the mansion’s garden but no people.

Swans in the lake in Buitenzorg Botanical Garden

(Appended from the author’s private album)

A big tree in the Palace’s garden

(Appended from the author’s private album)

Walking around there, I thought it would be more appropriate to describe it as a deep forest rather than a botanical garden, but for the plates with scientific names carefully put up at the sides of all the trees. I do not know how many pages would be spent if I continued to write

about trees in the botanical garden according to my academic interest. I would only say that I eagerly walked around to observe the rare and fantastic plants with my curious eyes.

There was a stream in the Garden. Several Javanese were bathing and many others were angling on the upper side. Those scenes ensured my feeling that it was not like a botanical garden.

We were very tired and came back to the hotel.

Hotel Bellevue was in a simple building with a moss-stained red-tiled roof and white walls that suited the tropical countryside[19].

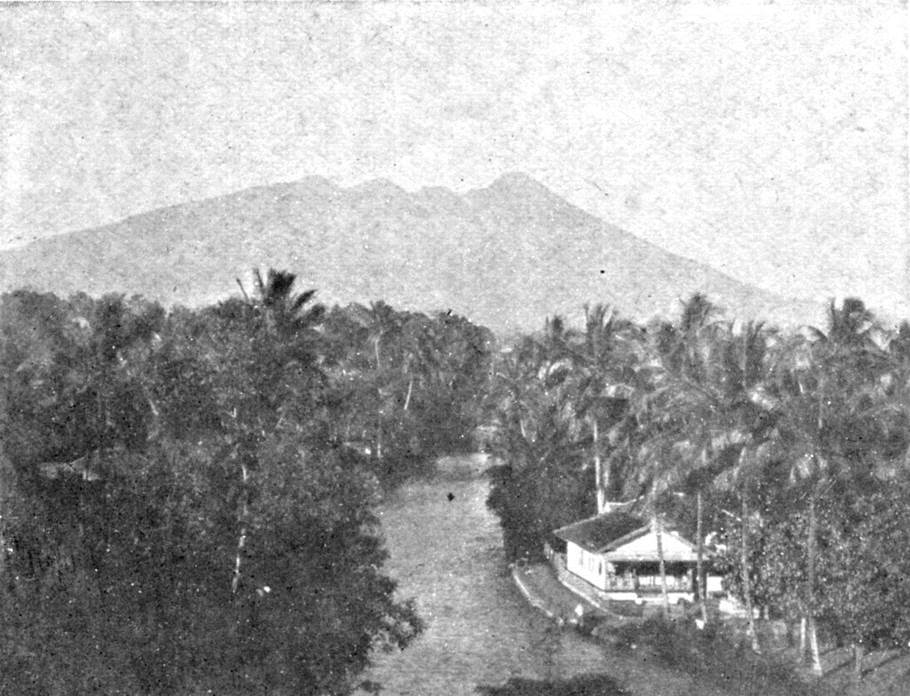

From the veranda, Goenoeng Salak, a volcano similar to Mt. Fuji in shape but with a less steep slope, was to be seen dominating the scene right in front. There was the River Sadane[20] below which, originating on the mountain, meandered into the palm-forest and ran through the village. Among the palm trees, there were the houses of natives with palm-leaf roofs and bamboo-woven walls. Villagers were washing sarongs and taking their bath in the turbid, fast-running water.

Goenoeng Salak from Hotel Bellevue

Hotel Bellevue, Buitenzorg

(Appended from the author’s private album

In the tropics where the transition between day and night is sharp, night reigns soon after the sun sets and the cool evening breeze removes the daytime heat. When I had a glass of ice-cold lemonade, I thought the taste was superior to any other good drink in the world.

I feel a little lonely when resting my tired body on the rattan chair and looking at the darkening scenery. It has been already one month since I have missed ‘the mountains and rivers of my home country’ and lost contact with intimate people. Although one month is not necessarily a

long period, it makes me feel especially lonely that I have no means to hear from my family and friends and I do not know when I can contact them again.

For an absolutely lonely traveller wandering beyond the southern sea, it seems that the fact that he has crossed over the equator is the cause of the feeling of being so isolated from the north, rather than the actual distance of several thousand miles over the ocean that separates him from his home.

What had made me most upset in hotels in Java was that one cannot speak to jongos without a command of Malay, although it is certainly acceptable that they are Javanese people with batik caps and sarongs, and bare-footed. Everything was basically arranged by Mr. Yoshii. When necessary, however, I would communicate with a few words of the local language that I had acquired urgently, as well as by gestures, without understanding what they say at all. It is a little lonely to be placed in a one-sided conversation when one has a mouth with which to speak and eyes with which to see.

It seems strange that the hotels are not equipped with electric fans anywhere despite being in the tropics. They say that those are the kind of things which country people use in colder countries. Since it is no use to agitate the air artificially and try to make it cooler in these districts, people do not wipe off but let their oozing sweat dry naturally, and wait until the cool evening breeze comes to let them forget the daytime heat, instead of turning a noisy fan. Life is quite simple.

A Dutch-wife is provided on the bed everywhere but only a thin cloth is provided, or often not, as material to cover one’s body. I do not know how it is for the Javanese and the Dutch but it is so cold rather than cool, for us Japanese, particularly in early morning, that I am surviving by holding the Dutch-wife to my front and back alternatively. ‘Even Shakyamuni did not know’ and he failed to advise that one would be shivering in the tropics. Then, why would a hotel manager know? For a while yet, the Japanese has to be trembling in the cold air.

Another story about the cold is that no hot-water bath is provided in hotels. There is a big cistern in the bathroom and one pours water onto one’s body like a water imp or a seal. It is not a problem in the daytime but people shrink at the coldness of the water, unless they are accustomed to cold-bathing from their childhood and their skin is numb, like myself.

When I came back to the hotel from outside in an evening, I found a Javanese man was sitting in the corner of the corridor with a big sword on his waist. He was there as if ‘A hero spends leisurely time days and months’[21]. Since he did not look fierce nor wild, I passed by him and returned to my room. Later, I was told he was a djaga (m. night-watchman). Twice, I became anxious as to whether the hotel was so dangerous that a night-watch needed a sword.

There are many interesting things to relate but I shall stop here, otherwise it will go on endlessly.

From the Research Centre to Bandoeng

The 30th of May. Early in the morning, I went to visit the museum holding zoological specimens[22] and the laboratories for botanical research annexed to the Botanical Garden under the guidance of Mr. Iwai who owned a shop in Buitenzorg and Mr. Tsukuda who arrived here late last night. In the museum, there were a number of marvellous specimens of elephants, buffaloes, tigers, rhinoceroses and other big game. Rather than appreciating the nice collection, I thought how wonderful it would be if they were alive and I could meet them in the jungle[23].

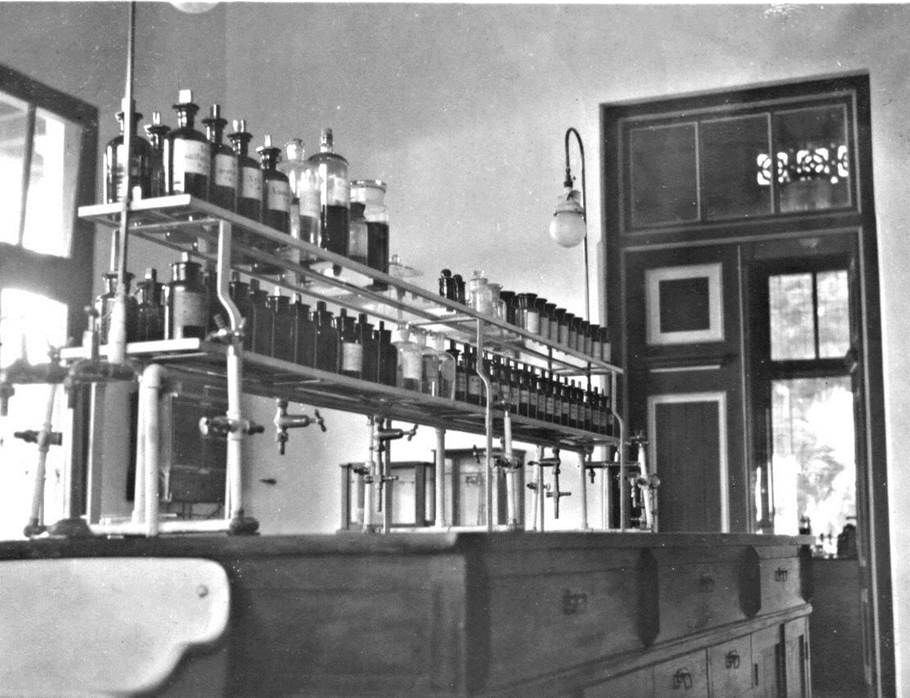

The laboratory built in commemoration of Dr. Treub[24] was most well equipped and open to visiting researchers from overseas. There were many microscopes and abundant chemicals, books and materials which were put at anyone’s disposal. A young fellow from abroad, called Dr. Boschma[25], showed me around. He took out a number of frogs from a box which he was studying. They were not special frogs but he said he employed them for his study on the response of nerves against stimulus. The facilities were extremely good and I wished I could have stayed there for a while and be engaged in my work free from any disturbance.

A bust of Melhior Treub in the laboratory

(Appended from the author’s private album)

A laboratory in The Treub Laboratorium

(Appended from the author’s private album)

After seeing Buitenzorg, the four of us returned to Batavia and took an express train for Bandoeng at two o’clock.

We arrived at Bandoeng shortly after sunset. I felt more or less depressed while taken in a rather dirty horse-carriage and driven along a dark street, until the vehicle entered a bright street and arrived at an unexpectedly good hotel. The hotel was the Hotel Preanger named after the surrounding district. It was a well-equipped, fine hotel, far better than Hotel Bellevue.

Bandoeng is a Europeanised, brilliant and beautiful city managed by the cleanliness-loving Dutch people. It is not a large city but it is a strategically important place, surrounded by fortresses[26], where the military

headquarter of the East-Indies is located. Since Bandoeng lies at a height of 2,300 feet, the air is unbelievably cool for the tropics. I felt as if it were autumn when I took a bath.

I have nothing much else to write about Bandoeng where I stayed just for a short time.

The 31st of May. At the suggestion of the hotel manager, we started early in the morning by car to visit the town of Garoet. It was quite pleasant to drive on a whetstone-like road in the fresh, fragrant, transparent morning air of the tropics. For the 63km to Garoet, the car flew like an arrow.

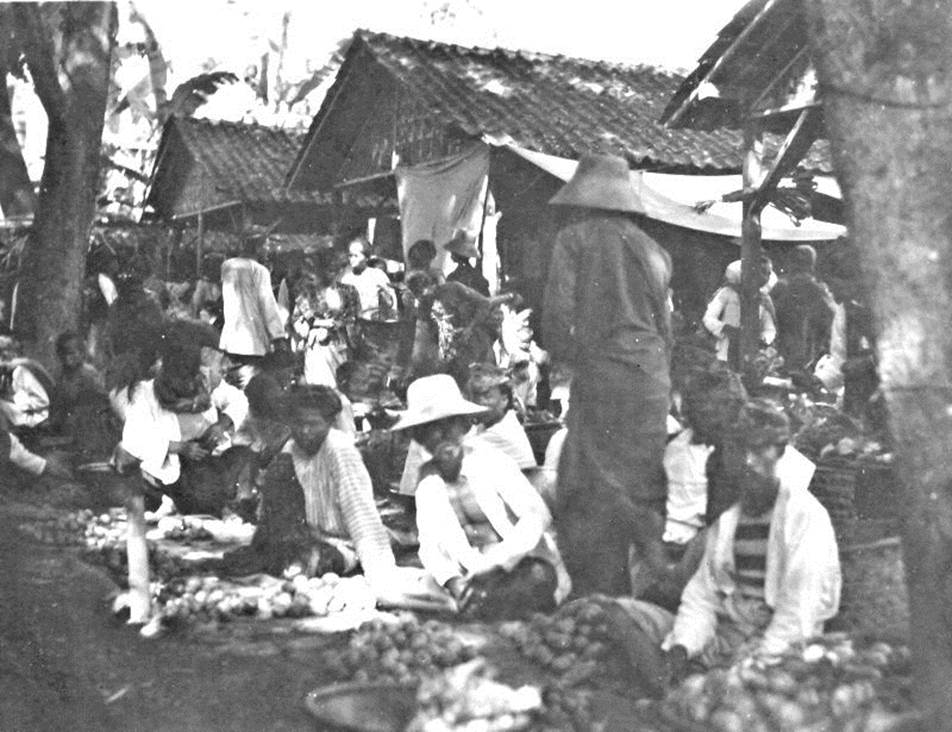

The car entered a small town called Leles. It was a purely native village, with no smell of the Dutch, in which small, humble houses were aligned in a row. As it was in the morning, a market was open in a square in the town centre and many people were gathering. We stopped our car to look around. It was full of people. Some retailers were selling cheap batik and other simple daily-goods in shabby huts, but many others were sitting side-by-side on the ground under the shade of trees to sell various foods placed in deep or flat baskets. Among the vegetables, fruits, dried fish and other items, I was attracted by something which looked like candies. There were snacks similar to karinto[27], marbles coloured in red and white, blue-and-red sugar candies and others which were too strange to describe. I thought the unsophisticated colours and shapes matched the ever-lasting summer country well.

A market in Leles

(Appended from the author’s private album)

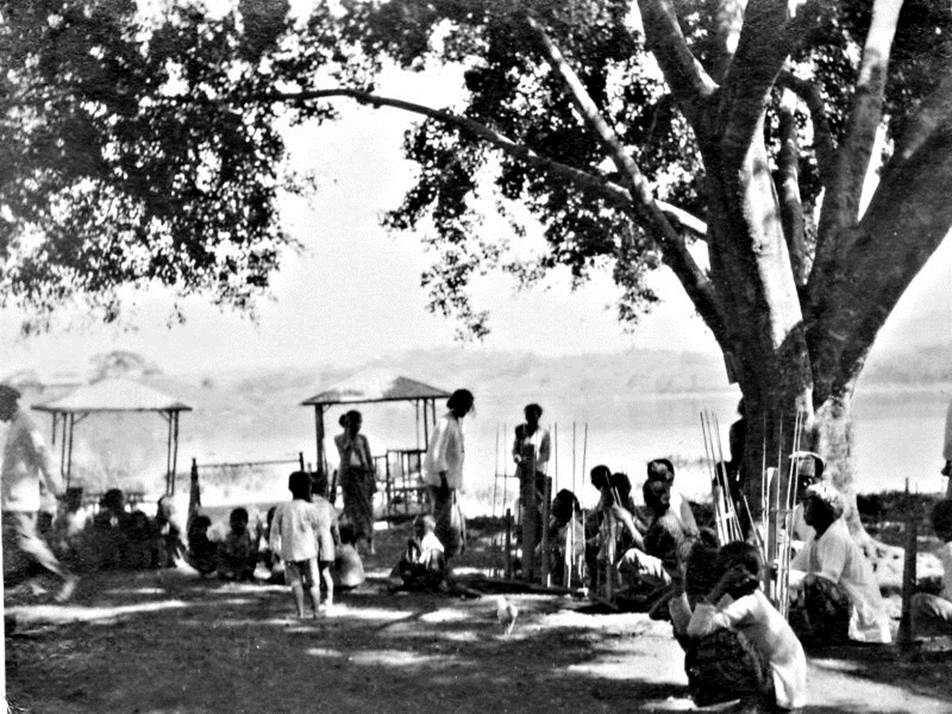

Driving a little further from Leles, we came out at the edge of a lake called Bagendit. Perhaps it was better called a bog, as reeds and other plants grew on the shore. Bagendit meant ‘a short sword’ and the name originates from its shape. There were seven or eight cozy houses, similar to insect cages[28], with thatched roofs and bamboo-woven walls.

Hearing the noise of the car, villagers with bamboo-made instruments, called angkloeng, came out and sat under the shade of trees at the lakeside. The instruments were made of bamboo tubes cut to an appropriate length by leaving a node so as to rattle when they collided. The tone was fixed and seven pieces formed a set. When they shook their instruments, holding one each in their hands, an organised melody was orchestrated. It was a primitive but deeply exotic music.

Lake Bagendit

(Appended from the author’s private album)

While we were absorbed in the angkloeng, village girls holding marsh-mallow flowers or cardinal-red roses came and stooped on their knees in front of us. When we received them by giving some pieces of copper coins, they smiled and said, “Terima kasih (thank you).”

They said those girls could also entertain visitors with angkloeng on a little boat, but we returned to the car as we had no more time. When the car began to move, the girls threw more flowers into the car and the elders celebrated our departure, saying, “Selamat djalan! (Have a safe journey!)” In spite of their kindness, the flowers drooped in the hot wind before we drove a mile.

We entered the town of Garoet, well known as a hot-spring resort, at around noon. It was a half-Europeanised, well-ordered town, having a calm and neat atmosphere. Surrounded by mountains and with clear water, it was a nice place like Hakone[29]. The driver knew the place well and brought the car to Hotel Villa Dolls. Since it was a little too early for lunch, we wetted our dry throats with tea. Then, strange music was heard approaching us from a distance.

A group of four men appeared in the front garden of the hotel. Two of them were carrying a big bamboo pole of six inches in diameter on their shoulders, from which a pair of four-foot long, ladle-like things hung on the front and the rear sides. The hanging objects were shallot-shaped, head-sized balls wrapped in bamboo-sheaths or palm-leaves. The third man carried something like a tuning-key and the fourth had an instrument like a fire-blower pipe, five-inches in diameter and three-feet long,

equipped with a mouthpiece. When we gave them a little money, the tuning-key-man and the fire-blower-man sat on the grass and played music, and the two pole-men swung the balls to generate fricative sounds of bamboo and string. That was all. It was too funny to be interesting but it was a strange show. We learnt it was called a torankong.

Listening to torankong music

After driving around Garoet, we came back after midday at half past two and took lunch. During the hottest hours of the day, I had a nap with a Dutch-wife until past four o’clock.

Bandoeng is a town of the night. When the sun sets and cool wind blows, evening-stalls open. The scene of putting up lamps and selling humble things were no different from Japan.

We found a booth located between houses and went inside to see what was there. There was an open stage and two bands with Javanese instruments were sitting on the ground. When they started to play their drums, lutes and gongs, Soendanese girls with white powder on their dark faces and wearing batik sarongs appeared walking with a mincing gait and lit the lamps. Soenda is the name of this district and it is famous for its ‘production’ of beautiful girls. Those girls were dancers. When the music started, the guests competitively payed money to dance a dance with dancers, which was not so interesting for us.

There were other miscellaneous entertainments such as an ad-lib play, a magic show and films. There were many stalls which sold peculiar items too.

1st of June. At half past four in the morning, while it was not like the dawn in the north, a jongos came to wake me up. I was still very sleepy. It is surprising that trains start so extraordinarily early in the morning. Hotels here are used to it however and breakfast was ready at five o’clock.

On the Javanese railway, most express trains depart at six in the morning, when it is still cool and comfortable. They do not operate at night. One reason why they start so early in the morning and stop in the night is that people go to work early in the morning, wishing to have a nap in the afternoon and to relax during the night. It is only my guess but it seems right. The second reason, they say, is that the authorities employ Javanese for low wages, as the Dutch are too expensive, but they cannot trust Javanese workers who tend to dose off while driving trains in the evening.

Also, for economical reasons, they burn wood that is abundantly available in the tropics, instead of expensive coal[30]. This is troublesome. That the ash should change white shirts into grey is not surprising but one must also be aware of the sparks of fire that often come into the passenger carriages and burn holes in one’s clothes. So, one cannot dose off comfortably, without the fear of being burnt. In any case, trains in Java are not convenient vehicles.

The diner carriage was not much different. A mandor (m. chief waiter) came to get orders for lunch at around ten o’clock and offered two menu items, beefsteak and nasi goreng (m. fried rice). When we ordered the former, he gave each of us a ticket, similar to a train ticket, on which was printed ‘Biefstuk’.

When we went to the diner at noon and produced the tickets, they served a plate of beefsteak, a bowl of green-peas and a bowl of potatoes, and that was all. The size of the beefsteak was so extravagantly large that even an elephant would surely say, after eating it, “My stomach is full and it is enough for me”. I was much impressed by the vitality of the Dutch who ate such a volume of food, while saying they had not much appetite in the tropics. At two o’clock in the heat of midday when our white shirts turned almost grey, the train arrived at Jogja where the Sultan’s palace stood. Within 20 minutes, we started by car from Hotel Grande by car to visit Boroboedoer, the famous Buddhist monument.

The car ran like an arrow between the green lines of trees. Beyond the vast sugar-cane field on the right, Goenoeng Merapi was showing its elegant profile that, covered by deep-green vegetation, did not look a ‘firing volcano’. A pale string of smoke rising up into the deep-blue clear sky indicated it was a volcano.

The driver pointed ahead to indicate the appearance of Boroboedoer. The Buddhist monument looked like a small mountain between the trees.

After we got out of the car and walked a while, we came to a flat place where the crown-shaped monument stood high in front of us. There was the Hotel Boroboedoer, a humble hotel for visitors. After a short rest, we went to see the cathedral by asking a hotel man to be our guide. At the entrance, there was a Japanese who was taking pictures accompanied by a Javanese assistant. We came close and introduced with each other. He was Mr. Hidenosuke Miura from an art college[31] who was there alone to study the monument, staying in the lonely hotel. He was taking pictures of the monument earnestly by placing a camera under the ‘gold-melting’ brilliant sun. “I came here on a three-month schedule but the study cannot be done in such a period. I will stay at least two-months more.”, he said. Mr. Miura offered himself to guide us and explain about the monument in detail, sparing his precious time.

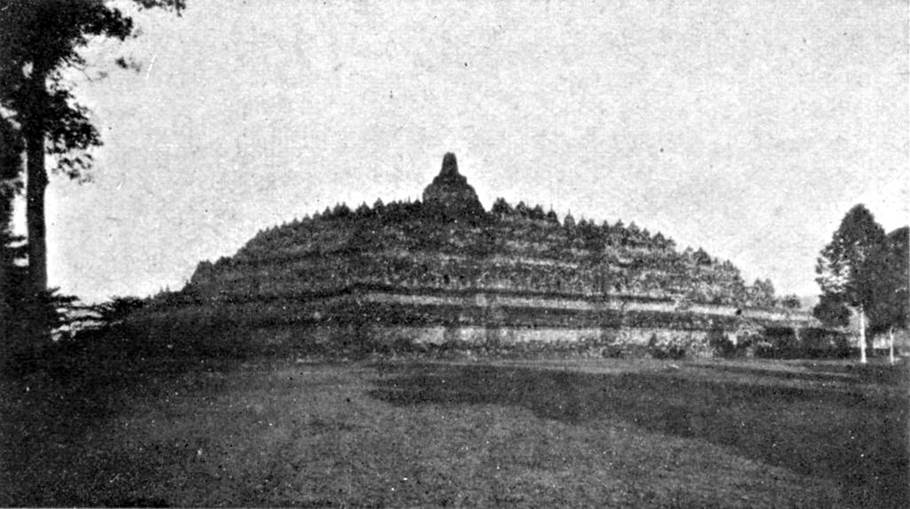

A distant view of Boroboedoer Buddhist monument

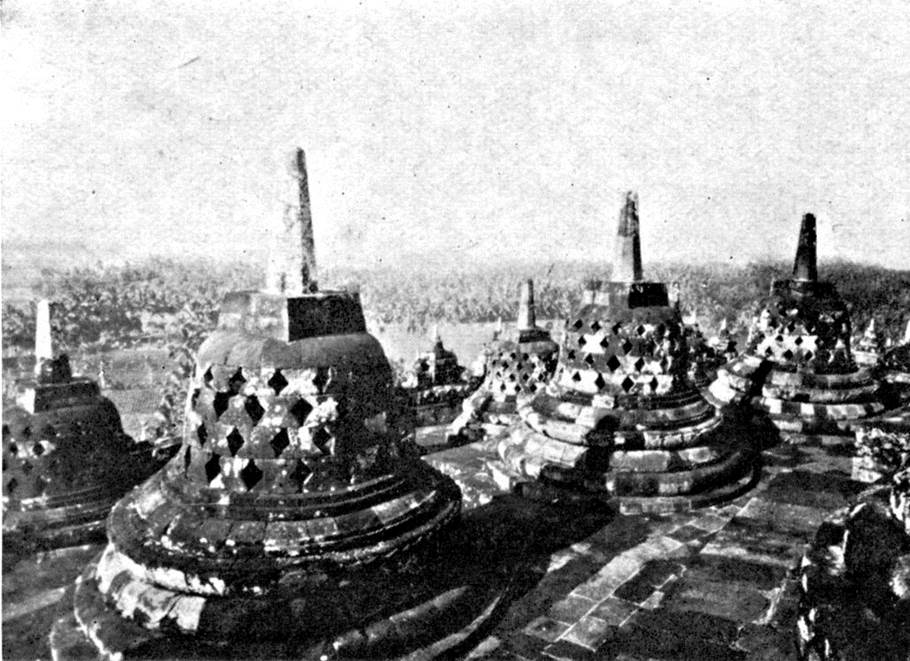

Stupas on the Boroboedoer monument

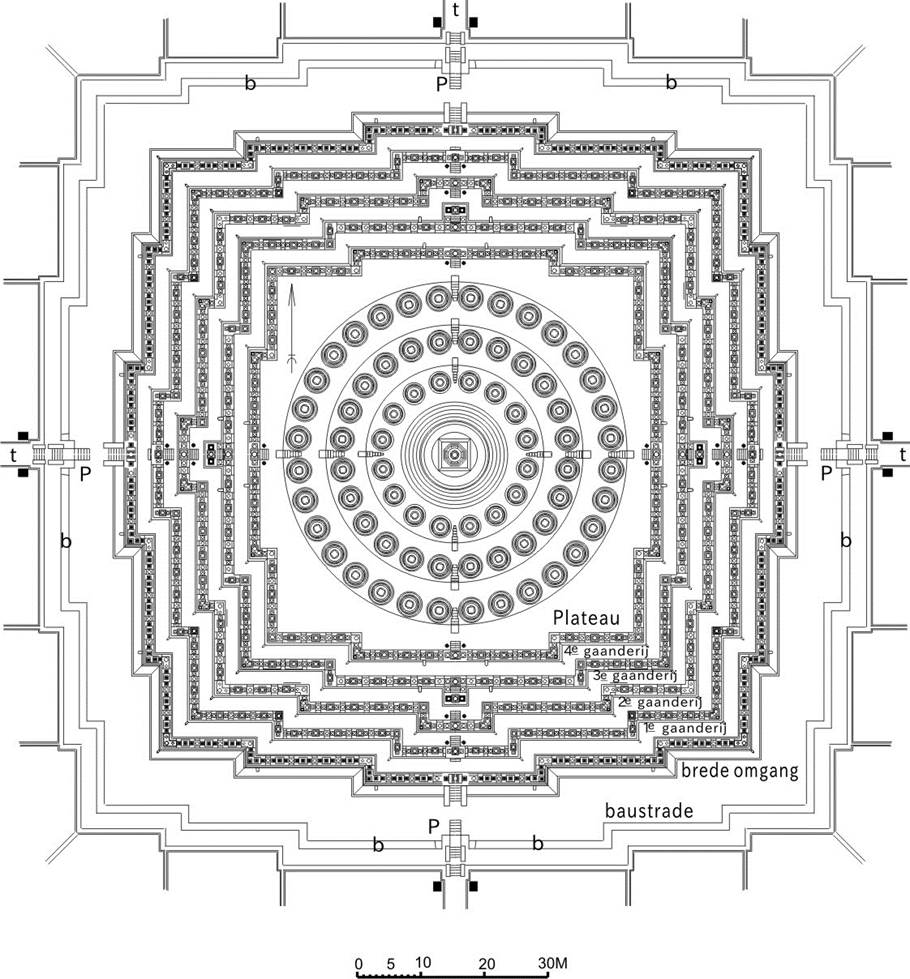

Plan of Boroboedoer

Reproduced from: Stutterheim, W. F., Pictoral history of civilization in Java. Translated by Mrs. A. c. de Winter-Keen, The Java-Institute and G. Kolff & Co., Weltevreden, 1926

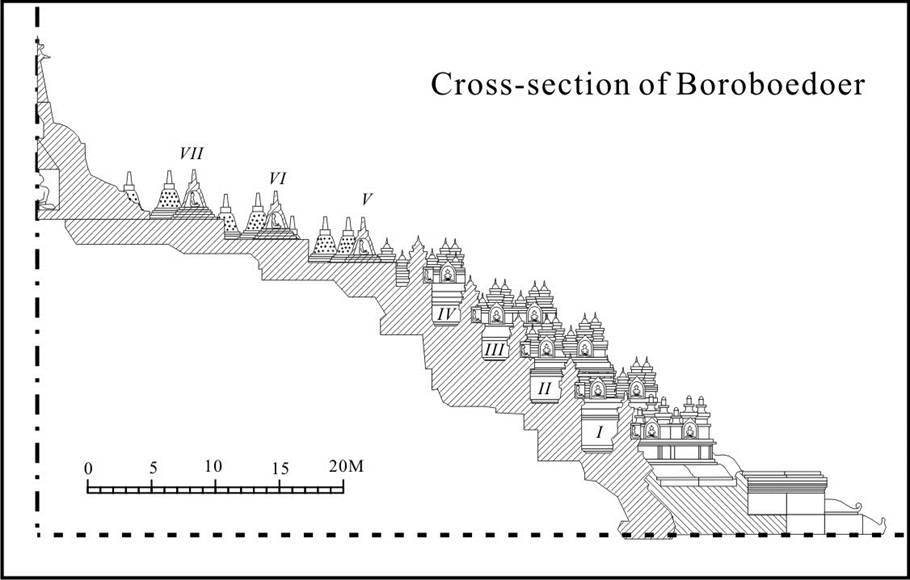

Reproduced from: With, Karl, Java - Brahmanische, Buddhistische und Eigenleige Architektur und Plastik auf Java, Filkwang Verlagg. M. B. H. Haben 1.W. 1920

This miraculous cathedral, the Buddhist memorial of Boroboedoer, was built of rough-surface blocks of igneous stone on a 600 foot square foundation of some 100 feet in height. From a distance, it looked like a great crown. When I got close to see it, I was completely amazed by the beauty and elegance of the reliefs carved on the rough stone surface.

The history of this splendid and wonderful monument is scarcely known, and that not a single document exists is an open question. It is assumed that it was built in the ninth century when Buddhism was at its most prosperous in Java[32]. The cathedral of Boroboedoer had been covered under the soil for a long time, before it was excavated, and why it was buried is not clear either. One source believes that, when Islam entered and prevailed at a great speed in Java in the late thirteenth century and Buddhism was overwhelmed and nearly extinguished, a small number of remaining Buddhists covered it with soil, lest the holy monument with Buddha’s bones inside should be trampled by the Moslems. Another thinks that it was covered with volcanic ash when Goenoeng Merapi erupted[33].

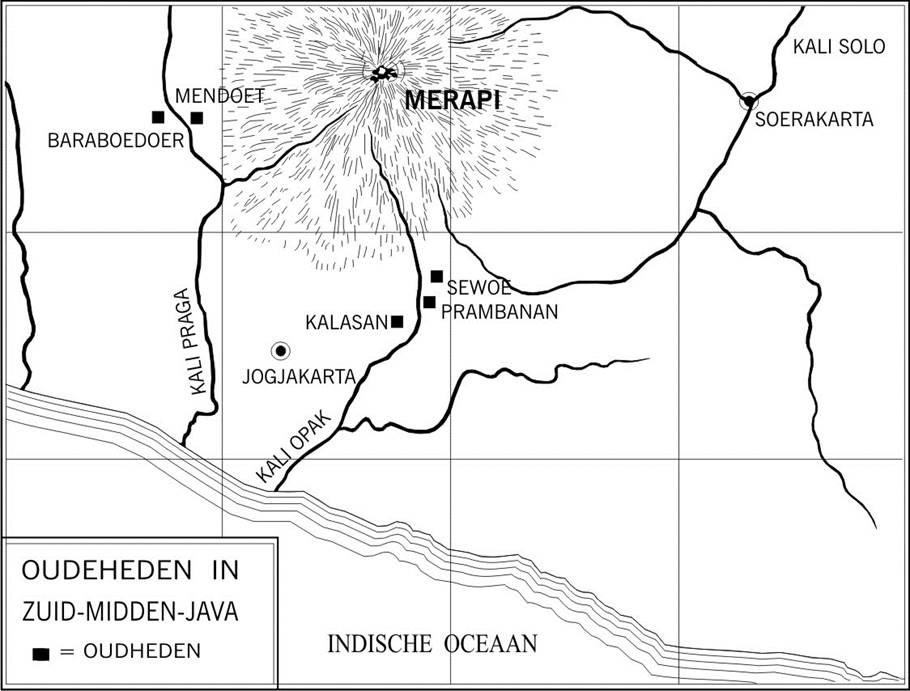

Map of south-central Java

Reproduced from: Stutterheim, W. F., Pictoral history of civilization in Java. Translated by Mrs. A. c. de Winter-Keen, The Java-Institute and G. Kolff & Co., Weltevreden, 1926

Whatever the reason, this Buddhist monument was able to show us one-thousand year old art in such a perfect and fresh condition without being corroded by ‘winds and rains’, having been preserved under the soil[34]. The monument which had remained under ground and been unknown to people was discovered by chance in 1814. The Governor-General, Sir Stamford Raffles[35], when Java was under British control, recognized its immense value and immediately ordered it to be evacuated. The Dutch government which took over Java again[36] also recognised its value and spent enormous funds and labours for its excavation and restoration[37]. Photographs taken at the time of the excavation showed that the monument had been seriously destroyed to such an extent that its original shape was not recognised. It was quite stunning that how they were able to study the shapes of blocks one by one and fit them together again to rebuild it. The Buddhist monument even looked more precious, when I thought over the time and effort that had been spent for the restoration.

I have used the word ‘cathedral’ but ‘pagoda’ may be a better word[38], because it is not a building as such but a stone construction laid out in such a way as to cover a mound[39]. There are eight stages surrounded by stone corridors, the bottom five and the top three of them being square and circular, respectively. The corridors of the square part have walls on both sides upon which the whole life of Gautama is displayed in fine reliefs. At intervals, there are Buddha statues placed on pedestals. The fine carvings are still sharp and do not look more than a thousand years old, since fortunately they had been buried in the soil for a long time. These fantastic carvings with delicate and dynamic lines guide the viewers into a land of fantasy. Mr. Miura said, “It is interesting, isn’t it? The life of Javanese people depicted here of more than one thousand years ago is not so much different from the life of today’s Javanese.” Truly, the ‘years and months’ of one thousand years may be but a time of a short sleep in this paradise of fantasy of ever-lasting summer.

There are 432 Buddha statues altogether. On the top three, circular stages, there are no walls with carved reliefs but only many Buddha statues each housed in the middle of a bell-shaped stupa, made by laying stone-blocks in the form of an open basket structure, 32 pieces on the sixth, 24 on the seventh and 16 on the eighth stage, whereas open pedestals are used on the lower stages[40]. On the top stage, or on the summit of Boroboedoer, there is a tower, the top of which is broken for some reason. They say that a big unfinished statue was found on a pedestal in the centre of this tower, and that there was a secret corridor that led from the edge of the tower to a cellar which would have been used for secret meetings. The unfinished statue is remains as a mystery.

When I had a look from the side of the tower, the red sun was about to set behind the mountains that stood in the distance beyond palm fields. It was a gorgeous sunset at an ancient Buddhist monument. What a quiet and tranquil scene it was! The glory of the sunset made the lonely traveller’s loneliness even deeper.

In one of the basket-type stupa, there was an offering of flowers. Unlike in Japan, they place only the petals of red and white aromatic flowers[41]. They said if one could touch the statue by putting one’s hand inside through the hole in the basketwork, one’s wish would come true. How many pilgrims from foreign lands would have tried to touch the statue when making their wishes? Some of them would have returned home disappointed without success. I was able to do it by inserting my arm up to my shoulder and I was delighted, while knowing it was a mere superstition. I don’t think my wish will be realised easily, because it is a very difficult one.

I felt sad to leave the ancient Buddha monument but made farewells to the pagoda and Mr. Miura, as it would soon be dark and there was not even moon-light to help me. I returned to Jogja under the glowing stars in the clear night sky.

In this country of fantasy of ever-lasting summer, another place that leads travellers from foreign countries like us into a dream, is Jogja, the capital of the Sultan. Aloof from the ceaseless progress in other worlds, the dream capital alone stays unchanged from the past, retaining the feudalistic system and keeping the classic, elegant air.

On the roadsides, there were rows of big, tall banyan trees with heavy green leaves, which would need ten people to encircle, covering the people in the street. Among the native people walking in the street, those who especially attracted us were the warriors serving the Sultan. They wrapped a batik cloth on their heads around their bunched hair, wore a jacket with loose sleeves and a batik sarong, put a keris in their waistband, and were walking in the street in a dignified manner in their bare feet, looking down on other people. Even when a shower came and others rushed along holding the hem of their sarongs, the warriors walked calmly without changing their step. It is undeniable, however, that the wind of civilisation blows, as cars are now pouring dust over those warriors. There was a car which had a gold-painted pajoeng[42] standing vertically at its side. They said it was a car of the Sultan. Such a pajoeng was the symbol of the royal family and the status of each member could be recognised from the colour of the parasol, the higher the position, the larger the gold part. It seemed to be the extreme of anachronism that a brilliant gold pajoeng was placed on the modern cars.

Several thousand warriors paid by the sultan have their houses around the Keraton[43]. Their houses stand on the sides of roads with many trees, surrounded by clay walls, similar to the warrior area in old Japanese cities. The payment they receive is in cash, not in rice as in old Japan, and it ranges between 90 cents to Dfl. 9,000 depending on their rank. They present themselves faithfully at the palace in shifts of one to two weeks.

Jogja is also a batik town. There are many shops in the streets displaying beautiful batiks to attract people. Mr. Sawabe, the owner of Fuji Yōkō Store in this town made his fortune by the batik business. In his factory, many Javanese women were drawing the patterns of batik in wax. I thought there is little work in the world that needs such labour. They said some batiks need two months just to draw patterns in pencil before the wax is put on and dyed, and the total process to complete a piece requires two to six months, or often one year. There is no doubt as to their high price. Nowadays, there are printed ones. Since it is not so easy for ordinary people to distinguish whether a batik is hand-painted or printed, they are often cheated.

Ten miles away in the suburbs of Jogja, there is a small town called Prambanan where the famous remains of a Hindu temple complex can be found. Guided by Mr. Sawabe, we travelled by car, scattering the dust during a ten minute drive to enter the town.

After getting out of the car, we walked for a while, panting in the midday heat, to the remains of the temples, where many fragments of igneous stones were scattered randomly. When I had a close look, there were some traces of carvings on each piece, and some pieces retaining the carvings in more or less perfect condition were laid at the side of the field. In the middle of the field, there were a couple of pagodas which were heavily damaged but retaining the image of their original forms[44].

These vast remains used to form a Hindu temple complex, alternatively called Tjandi Lala Djonggrang[45]. Although it was a construction of carved igneous stones and the scale was similar to Boroboedoer, it was much different in structure, originally comprised of eight big pagodas standing in the centre and 157 small ones in the surroundings. It had been buried in the soil like Boroboedoer until it was discovered accidentally by a Dutch official in 1790[46] and its restoration was begun in 1885[47]. It was miserably broken and, among the eight pagodas, which were placed three each on the east and the west sides and one each in the south and the north sides, only the three on the west and one on the east side remained in such bad condition that even assuming of to guess the original shapes was quite difficult. Even the best one in the middle of the west side, on

which the restorers had worked for 30 years since the start of restoration, was not in good shape.

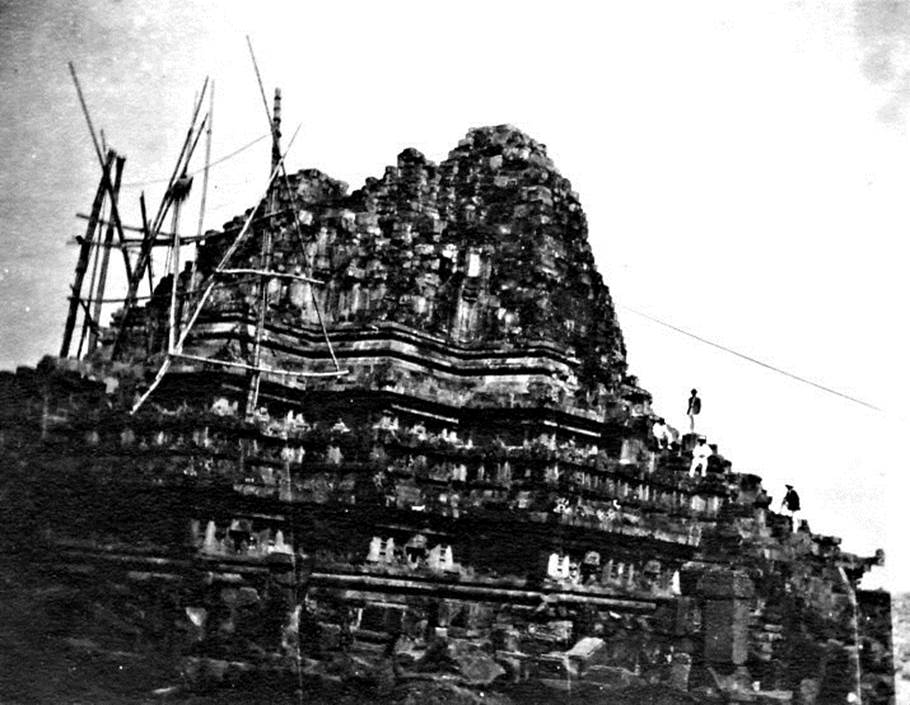

A destructed temple of Prambanan

(Appended from the author’s private album)

The history of this temple complex is not known either but it is supposed also to have been built around the ninth century at the same time as Boroboedoer[48]. The brilliant merciless sun beams scorched the stones, heating my shoes so as to almost stick onto its surface, dazzled my eyes and burnt my face, as if I were receiving a ‘roasting-in-a-pan punishment’. A traveller who could not expect to visit here again however had to stand the punishment to take this opportunity to see the sights.

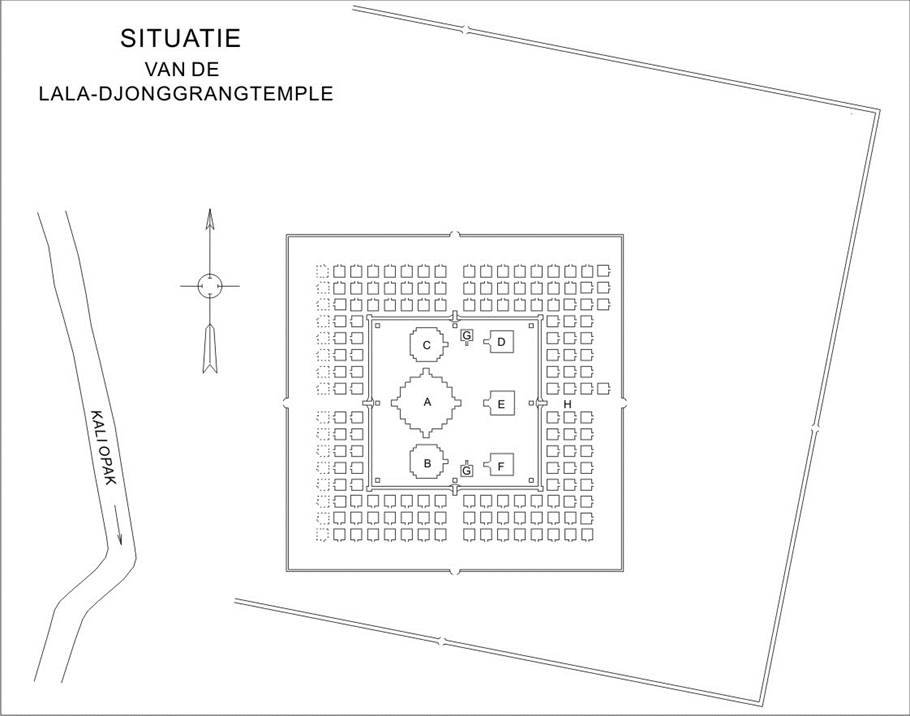

A: Shiva-temple, B: Brahma-temple, C: Vishnu-temple, D-F: Temple dedicated to the mounts, G: Temples of unknown destination, H: Four rows of small temples

Reproduced form: Stutterheim, W. F., Pictoral history of civilization in Java. Translated by Mrs. A. c. de Winter-Keen, The Java-Institute and G. Kolff & Co., Weltevreden, 1926

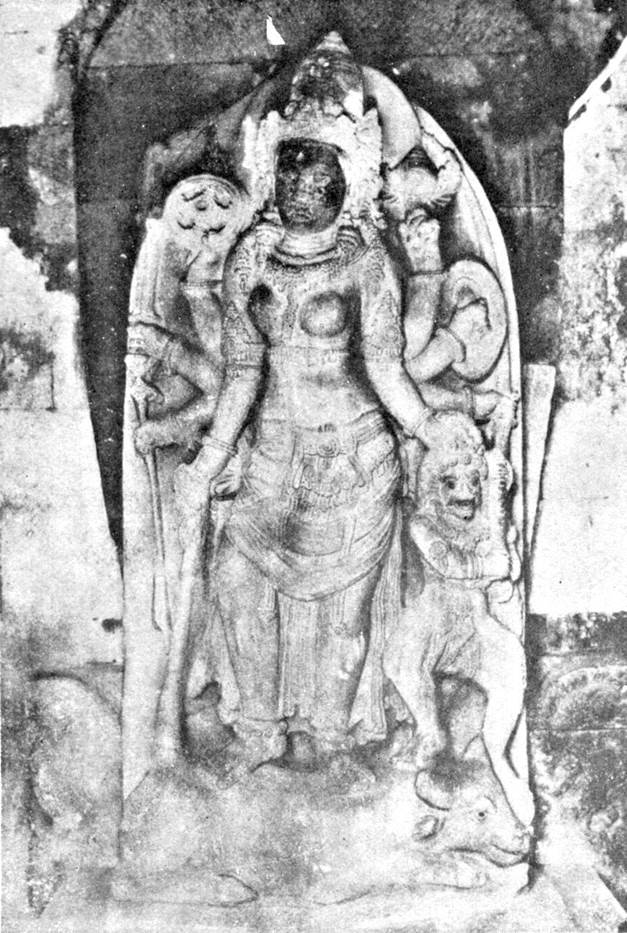

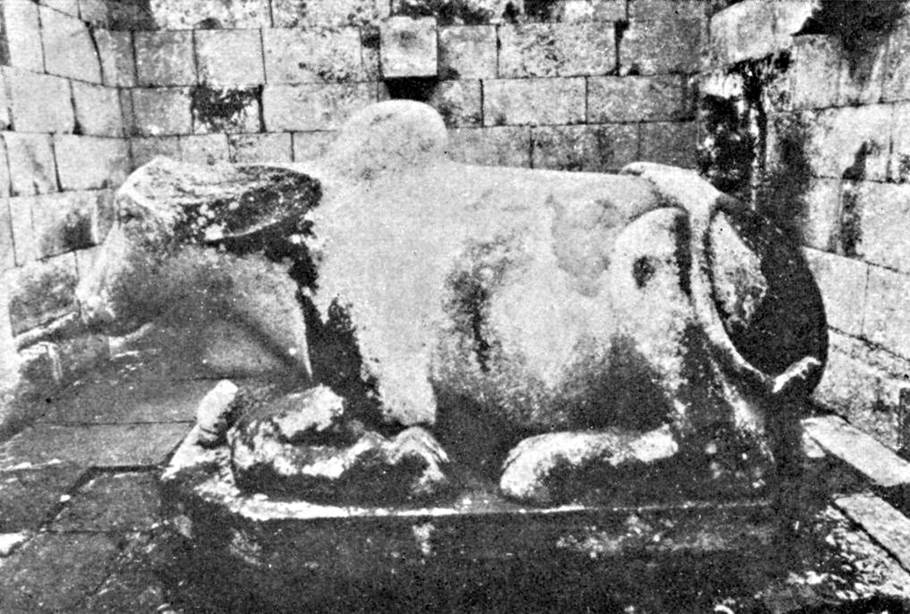

Pagodas are built on square foundations by laying pieces of igneous stone furnishing four pedestals on the four sides to face outward. In the biggest one in the middle, there was a statue of Shiva, the God of Destruction on the southern side, on a 20ft square pedestal. The four-armed god was posing on an ox with a snake around his waist. In the next chamber, there was Ganesha, the son of Shiva. He was an elephant with a big head, putting his preeminent nose in a bowl held by his left hand, looking charming for a child of the Destroyer. In the third chamber was Shiva transformed into the shape of Mahaguru. In the last chamber was Durga, the wife of Shiva, also riding a bull. She had eight arms, holding the hair of Asura, the Satan, in one of her hands and various weapons in others. Perhaps, this statue is one of the masterpieces. Her pose is not such that will lead a viewer into a pious feeling, but is rather erotic. Although it was carved from a cold stone, she looked quite soft, as if warm blood streamed underneath her skin. I thought that the sculptor would have wished to express his carving, not as a goddess, but as a human. Perhaps Javanese people, having their own optimistic thoughts conceived through their easy style life in the tropics, might consider a god, or a goddess, as a close existence to people, rather than putting him, or her, a aside in a remote place. In any case, it was quite wondrous to imagine the vitality and efforts of an ancient artist who had made such a marvellous work with a chisel, whether he was motivated by his religion or by his dedication to art.

The statue of Lala Djonggrang

The name of Tjandi Lala Djonggrang comes from this masterpiece. The related legend also suggests that the statue’s aim was for people to appreciate the beauty of a human rather than that of a goddess.

When I got out of this pagoda and looked around, the neighbouring pagodas housing Vishnu, the Preserver of the world, and Brahma were more seriously ruined. As a whole, the condition of Prambanan was much worse than Boroboedoer. Although many parts are lost, perhaps due to theft[49], the reliefs carved on the rough stone are fabulous, and the dynamic and delicate touch deserved the same or even higher praise than Boroboedoer.

The relief of three girls, or nymphs, is the best of the masterpieces and their amorous poses are quite attractive. Some carvings present considerably erotic poses which, if in Japan, the nervous Metropolitan

Police or Ministry of Education, or both together, would take measures to prohibit their exhibition. The Dutch authorities, having respect and understanding of the arts and trusting that people are not so stupid as to have their public morals corrupted by seeing them, keep the carvings open to the public under the bright sun and let people take pictures or sketch them as they wish. On the pedestal of a broken pagoda, a statue of a bull of almost real life size lies. It is a lovers’ spot, for the religious Javanese believe that a wish of a couple will be realised if they come to pray here. I have thought over the unknown masters, or the grand artists of unknown time who left those splendid works of art, at these pagodas, that are comparable or even better than famous works in Europe. It is rather mysterious to try to imagine how it was done. In this country of fantasy, Java, I would think it was a miracle done within one night, as the legend said.

The carvings of Kala’s head and three nymphs

(Appended from the author’s private album)

The statue of bull which makes lover’s wish come true

It was once upon a time, long, long ago. In Prambanan, there was a king called Ratoe[50] Boko who had a beautiful Princess, Lala Djonggrang and a Prince, Raden Goerobo. The prince was not the king’s real son but had been adopted, by the mercy of the king, as the prince’s father had been killed by the king of Penging. When he grew up and wished to take revenge, he knew the king of Penging had a daughter. He proposed to her and, at the same time, asked Ratoe Boko’s help. Since the king of Penging immediately noticed it to be a plot, he planned to assault Prambanan and recruited strong men who could defeat Ratoe Boko. Two men whoappeared were Bondowoso and Bambang Kandilalas, sons of an ascetic, Dhamarmoyo who lived at the foot of Goenoeng Soembing. The

brotherswere told that they would receive either the king’s daughter or half of the country for a reward, and the war started. Ratoe Boko was not an ordinary king. Since he had an enormous nose-wind that could blow off anyone who came close, the two enemies were miserably defeated in two battles. In a fury, the mountain ascetic taught a formidably strong magic spell to his sons that, if placed, would give them the power of one-thousand elephants, not just ‘the power of one-thousand-men’. They collected men and challenged their rival again. It became a fierce battle as Boko’s nose-wind was not longer useful. The war cries shook the sky and the ground and a huge amount of blood spilled drained to form a lake, the present Danau Boinjan. The fierce battle continued. At last, Boko was pushed into the lake by the elephant power of Bondowoso, uttering a loud groan that reached all over the country. Even today, natives who live in the lake-side say they often hear its weak echo. Hearing the sound, Goerobo came rushing in carrying a magic tablet but he was shot by Bambang’s arrow.

The victorious brothers, Bambang and Bondowoso received the rewards as promised. Bambang married the princess and Bondowoso became the king of Prambanan. One day, Bondowoso saw the beautiful princess of his rival and proposed to Lala Djonggrang. She was not agreeable to marrying her enemy. She was afraid of Bondowoso’s anger and set an impossible condition, saying, “If you love me truly, please build and show me six stone temples and one thousand statues of Ratoe Boko in one night. Then, I shall obey you.” Bondowoso decided to try it with the help of his father, the king of Penging and Bambang. Dhamarmoyo placed a spell to call gnomes to give a hand.

They worked hard all through the night. When Lala Djonggrang came to see the progress, before daybreak, the temples were nearly finished. She went to the site where the gnomes worked and burnt a special incense which quickly made them powerless[51]. When the morning come, there were 999 statues, lacking but one. Bondowoso became furious and made a curse that the girls in Prambanan could not marry at a young age. They say local girls do not marry early, even today. He was also disappointed and called Lala Djonggrang. When she asked about the work, Bondowoso told her desperately, “No, one was not completed. You shall be the statue, instead!” The Princess turned into a statue, called Lala Djonggrang, which still maintains her beauty.

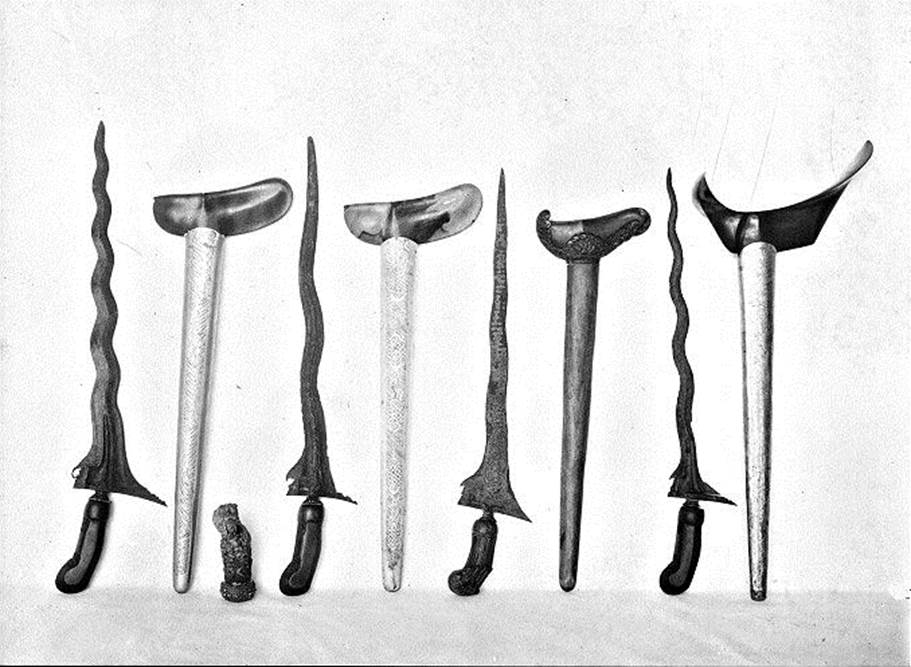

After our return to Jogja, Mr. Sawabe asked me to visit a pawnshop with him. While I was looking at his face wondering why, he said it was to buy a keris. We entered a rather uncomfortable shop in a crowded natives quarter. The master brought many keris from the back. The sword blades were about one foot long and did not have the appearance of ‘clear autumn water’ as of Japanese swords, but they had a number of narrow stripes from the hilt to the tip generated when the iron was forged by folding over many times. The shapes were various and the blades were either straight or bent in a horrible wave-shape. They were not to cut an object in half by a single blow, but to pierce straight from the front. They said those keris were forfeited articles. It seemed outrageous that warriors should put their swords in a pawn store and leave them unredeemed, but perhaps they could not manage to keep their living with a salary of only ninety cents, even if they wished to be humble. They said the shape of keris was also different between Jogja and Solo. The master also showed other kinds, a sword like a kitchen-knife or a hatchet used in the Keraton, a spearhead, and so on. There were also many sarongs which had stable colours developed by repeated washing. Perhaps they might bear some sentiment of their former owners, as sarongs are items of important property for the Javanese people. It was interesting that each forfeited article bore a label with the pawned price. When one buys, the master

calculates the price by adding the interest by abacus. In this way, they do not make undue profit[52].

Javanese keris

(Appended from the author’s private album)

In the west of the Keraton, there is a water-castle which is now a dreadful ruin. Although unknown weeds grow and bats and frogs live

there now, it used to be an extremely luxurious palace of pleasure in Java. It was constructed in 1758 by a Portuguese engineer[54] by the order of the King of Mataram, Sultan Hamengkoe Boeono who spent a most lavish life, but it has deteriorated to such an awful, miserable ruin. The castle was designed in such a way that the castle itself would float on flooded water for defensive purposes if the near-by river were dammed in an emergency. From its history, however, it was a palace rather than a castle, called the Taman Sari (flower garden) where Sultan Boeono had a southern -style, extremely degenerate pleasurable time surrounded by three thousand court ladies.

When I entered the stone-arch gate, which reminded me of a prison-gate, surrounded by three-metre high stone-laid walls, I was struck by the damp atmosphere. The front building was made of bricks. When we passed several rooms along a narrow, low-ceilinged corridor, there was the Sultan’s bedroom. It was a small room with an extremely low ceiling. Since the sun-light was shut out, the air was moist and cool. Black moss and fern grew on the ceiling and the walls which used to be gorgeously painted, erasing the past images completely. There was a stone bed in the middle. In the corner of the room, there was a tunnel, which a man could pass through by bending over, an escape to the Keraton. The Sultan must have been cautious even when he was enjoying his private moments. The building was seriously decayed and covered by ivy. At the place for the Sultan to pray, there was a stone-made dome situated over a pool where he washed himself. When I walked along a moss-grown slippery lane, there was a hall which was supposed to have been the keep. The inside of the underground corridor was dark and damp, and surprised bats took off as we walked through. After passing through the long, dark dreadful corridor which could be a scene of a mystery novel[55], we came out to the back of the hall. There were two pools in which beautiful women swam in the past, but now frogs were playing around the water-lilies. It was surrounded by walls to shut it off from the outside. The rectangular pools, each measuring about 100 square-metres, were floored with stones and there was a stone bower in the middle, from which the Sultan looked down at the swimming women. A beautiful one chosen out of many was taken to another pool to swim with the Sultan.

A scene inside the wate-castle

(Appended from the author’s private album)

The ruin of the dream of Sultan Boeono of Mataram, who had led an extravagant, luxurious life and enjoyed the extremes of corrupt and extravagant pleasure, in this ever-lasting summer country, surrounded by three thousand beautiful women! Today, it is nothing but a terrible ruin where weeds and palms grow, having been exposed to wind and rain for two hundred years. It does not show any trace of its past glory. While he was absorbed in dissipation and pleasure, the Kingdom of Mataram had been stolen[56]. On visiting Taman Sari, I remembered the phrase, “The country is shattered, and mountains and rivers remain.[57]”

When we came back to the gate after seeing Taman Sari, a young man came up and spoke to Mr. Sawabe. The latter turned to us and told, (He is saying a parade is going on in the outer garden of the Keraton.( It was not far from there. The outer garden was a square covered with white sand and there was a pair of waringin-trees in the middle, extending their branches in the form of a pajoeng used as the symbol of the nobles. Javanese people call them ‘pajoeng trees’ and believe the kingdom of the Sultan will be peaceful and secure as long as these holy trees grow[58]. When we arrived, the procession was in progress. I prefer the word ‘procession’ to ‘parade’ because it was far too out of date to be called a military parade. They said it was a rehearsal of the parade which would be held in August, on the Javanese New Year’s Day[59]. Although their dress for the exercise was not formal, they wore a uniform and put keris at their waists, and they were, of course, bare-footed. The retainers[60] receiving stipend from the Sultan ranged from teenage boys to white-haired old men. The procession was headed by a dignified standard-bearer and followed by officers with unsheathed swords, a band with flutes, trumpets and gongs, three rows of about ten spear-men in each, two pompous men with a spear at their sides, and about one dozen musketmen. The musketmen were quite appalling as the guns they carried preciously were old-fashioned muzzle-loaders found elsewhere only in museums. The above team formed one unit. Several such units, altogether more than one hundred men, calmly advanced in a composed fashion and in a long queue in harmony with droll marching music. It looked as if, right after one hundred years, the puppet-show of Watōnai[61] was being played by real men. I had never thought that such an interesting performance persisted up until the present, twenty years after the turn to the twentieth century and after the end of the Great European War[62]. Perhaps, the word ‘anachronism’ is unnecessary in Java.

There were many spectators gathering, including some people who were apparently the members of royal family from the Keraton. They were bare-footed also and even young teenagers had a servant with a golden pajoeng. A noble to whom I was introduced by Mr. Sawabe was an elegant young man of over twenty, though his rank did not seem high from his pajoeng. I only spoke a few words to him with the interpretation of Mr. Sawabe, because he did not speak English. I have thought there are many handsome young men with ‘elegant eyes and eyebrows’ among Javanese nobles, whereas those in our country are amazing[63]. Unfortunately, on the other hand, I have never seen a girl who “let one admire three times and forever”[64] as “casting dressed beauties of six palaces into shadow”[65], even among Sundanese beauties.

The man who proudly conducted the parade under the attention of thousands of eyes was a young, energetic officer of just over twenty. At his command, the units aligned themselves parallel to the waringin trees at their backs. It seemed that training for shooting was about to start. At the first command, the gunmen pulled out their rods and pushed them down the barrels for loading. Secondly, no sooner had they put their guns to their waist than the band hit their drums, while the spear-men held their spears horizontally. Mr. Sawabe said they imitated the sound of shooting with the drums. While we watched amazed, they repeated the ceremony three times, before the signal to finish was given. That was the end of the parade and the warriors retired as composedly as they had entered. Among the spectators were children of warrior families. One was carrying his father’s spear snobbishly on his shoulder, whereas another was walking ahead proudly with a gun borrowed from his brother or cousin. When I was told about the time around the Restoration[66], I was not able to believe that such sort of fantasy had existed in reality. Having been shown this today, fantastic Java became even more fantastic in my mind.

Wayang is an indigenous shadow-picture in Java played by projecting the shadow of flat thin puppets, called wayang koelit, onto a screen. The puppets are painted in gorgeous colours, made sophisticatedly from cutouts of buffalo skin, so that the joints of their neck, arms, and legs can move freely. Their shapes are quite grotesque in such a form that a sharp nose is predominant over skeleton-like thin arms and legs and the bee-like constricted body, while a swollen belly protrude ahead of the nose in another. When evening comes, temporary stages are set up in the corner of towns. Projecting the shadows on the screen, the puppeteer delivers the lines by himself, while a band plays music. Most of the dramas are classics based on old Javanese legends[67]. The projected shadow changes more fantastic by the casting of the lights. Wayang is a marvellous play which matches the night atmosphere of the country of an ever-lasting summer.

3rd of June. Before daybreak, we left Jogja for Semarang with a dreamy memory of the capital. In the boring train, I had slept for almost the whole three hours and a half until it arrived at Semarang. I drove around the city thanks to the favours of Mr. Tokumasu, the director of Mitsui’s local branch, but I did not see anything in particular. It was a commercial city and, coming from Jogja, I felt I was back in twentieth-century civilisation.

What surprised me was an old-fashioned type of transportation, i.e., a locomotive towing several carriages similar to grasshopper cages and moving around the city like a giant centipede. The living area was also clean in this city, with European-style houses placed under green-shades, as if they were in a picture. At one o’clock, we left Semarang once again on board De Melchior Treub bound for Batavia.

4th of June. The boat was already at the wharf of Tandjoeng Priok at seven, when the shades of my cabin door were lifted by the active chief-steward. Mr. Tahara came to pick us up. We had to be in a hurry because shopping and sightseeing had to be finished in the morning, before all spots of interest closed at noon on Saturday.

Amsterdam Poort in the old town of Batavia

(Appended from the author’s private album)

One of the attractions in Batavia is the museum[68] which holds native curios of the East-Indies in such a huge number that I wondered at how they have collected them. It was pity, however, that we were only just able to have a brief look round due to the lack of time. There were two more things to see. One was an old-fashioned cannon[69], four metres long, left in the grass field outside the old fortress of Batavia[70]. One may say that old cannons can be seen in the Yūshūkan[71] and, in fact, there are even older specimens there. This cannon was special as it had an enormous fist, five times normal size, cast together with the barrel at the rear. Although it is a kind of item that, if in Japan, would be placed in a special room and hidden from public eyes, the Dutch do not mind and leave it there openly exposed. Then, people are not surprised. A fist might symbolise a woman but, they said the cannon was a man, named Kiai Setomo. He had a fiancée in Bantam[72] and there was a belief that the day when the two cannons were to get married in future would be the biggest celebration day for Java, i.e., the day of independence when she can beat and expel the foreign powers. Many Javanese men and women donate five-inch tall lanterns made of red and blue papers together with cakes and keep burning incense incessantly, in another belief that they would be given a child if they visit here for pilgrimage, leaving aside the matter of independence for the time being.

Kiai Setomo, an old cannon in old Batavia

(Appended from the author’s private album)

The other attraction was a skull on the wall of a palm-oil factory. It is awful to see a skull in public today, but it is accepted in Java where they do not care about the regression of one or two hundred years. It is also strange to see it on a wall of a factory but it is more surprising that it has been there for two centuries.

It is the skull of Pieter Erberveld[73], a half-caste who had plotted to overthrow the Dutch in Java, but was arrested and executed in 1722, together with his 46 comrades. Underneath was the inscription[74]:

In consequence of the detested memory of Pieter Elberveld, who was punished for treason, no one shall be permitted to build in wood, or stone, or to plant anything whatsoever, in these ground, from this time forth for evermore.

Batavia,

14 April 1722

A long-time pilloried skull, indeed! This was the place where Erberveld had lived. During the two-hundred years since then, the house was demolished and a palm-oil factory was built in its place but the wall was left as it was, together with the skull, pierced by a spear-head sticking out three to four inches. It appeared to be made of cement but Javanese people believe it was truly real. It is frightening to think, if one betrays the Dutch, that one’s head should be made into a stone-like skull like this.

We finished our journey in Java with good memories of the dreamy country and returned to the Northern Hemisphere.

[1] A vessel which the author took from Japan to Singapore, starting from Moji on 5 May 1921. She was one of the first 8,000 ton steamers launched in 1906 and served on NYK’s European line. She was sunk by torpedoes near Iwo-jima in July 1943.

[2] A disparaging term for Tamil-Indian settlers in Malaya and Singapore. Kling (m. keling, j. kirin) is derived from Kalinga, an old name for a strip of coast as well as a kingdom located along the Bay of Bengal.

[3] A Japanese newspaper published at that time in Java.

[4] Tandjoeng Priok, Batavia, Weltevreden and Meester-Cornelis roughly correspond to present Tanjung Priok, Kota, Central Jakarta and Jatinegara, respectively.

[5] Chief of a foreign trading house. See, Footnote 61 of Part One.

[6] For Oharu and the letter, see Footnote 60, 62 of Part One.

[7] The tombstone (which was half the usual size) originally existed in a footpath near Kalibesar West. It was taken to the Anglican Church at Prapatan, and then moved to the yard of the Japanese Consulate at Kebon Sirih No. 28 ten years before the author first visited there in 1921. Despite extensive studies made in the past, the identity of Sobe(i) was quite mysterious (Haan Frederik de, Oud Batavia - Gedenboek uitgegeven Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen naar aanleiding van het driehonderdjarrig bestaan der stad 1919 (Eerste Deel), G. Kolff & Co., Batavia 1922). According to the records discovered by Iwao in the Landsarchief te Batavia in 1925-39, a rich man named Michiel ‘Diaz’ Sobe prepared a will on 29 March 1661 at the house of Simon Simonsen (Oharu’s husband) giving one third each of his property to Simonsen and two other persons. Documents of business contracts and testimonies signed by the same person also existed (Iwao, Seiichi, The Japanese Immigrants in Island South East Asia under the Dutch in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Iwanami-Shoten, Tokyo 1987). It is interesting that for the Japanese text Tokugawa chose the specific Chinese character, 惣, for the “so” of Sobe(i), the same character that appeared in the signature in the old documents, among many phonetic alternatives. (Did he learn it from Prof. Iwao and apply it when the travelogue was republished in the book in 1931?) The stone disappeared after the declaration of the independence of Indonesia. A rubbing of the inscription exists in the National Museum of Japanese History, Sakura, Chiba, Japan.

[8] The area is considered as the home of the Hindu Kingdom of Padjadjaran, which was defeated by Islamic Bantam and extinguished in 1579. The ruin of the old palace is believed to be buried underneath the present palace (Buitenzorg Scientific Centre, Buitenzorg Scientific Centre, Archipel Drukkerij en T Boekhuis, Buitenzorg 1948). An early settlement has been found in the area of Batutulis, a little far from the city centre, overlooking the Cisadane river. “Bogor” is said to originate from the name of an extinct species of pine.

[9] More precisely, Buitenzorg was originally developed as an estate of Baron Gustaf Willem van Imhof from 1745. The present mansion was built in 1856 and became the Governor-General’s official residence in 1870, when Pieter Mijer was in position.

[10] A distinguished scholar, Caspar Georg Carl Reinwardt (1773‑ 1854) was born in Prussia and received his education in Amsterdam. He was appointed the professor of chemistry, herbarium and natural history at the University of Harderwijk. After the reinstatement of Dutch authority in Java, he was ordered by King Willem I to advise the Governor-General there in 1816 and founded the Botanical Garden. In 1822 Reinwardt returned to the Netherlands and became the professor of chemistry, botany, geology and mineralogy at the University of Leiden (http://www.xs4all.nl/~rwa/gbbcr.htm).

[11] Starting with 47ha, the area of the garden was expanded under the directorship of Dr. Melhior Treub to 60ha in1892, and later to its present size, 87ha in 1927.

[12] Born in 1851, he received his education at Leiden University. He was the director of the Botanical Garden from 1880 to 1909. He passed away in 1910 with malaria.

[13] Before this, Alfred Russel Wallace had written in 1861, “The gardens are no doubt wonderfully rich in tropical and especially in Malayan plants, but there is a great absence of skilful laying out; there are not enough men to keep the place thoroughly in order, . . .” (Wallace, Alfred R., The Malay Archipelago (1869), Oxford University Press, Singapore 1985)

[14] Japanese name: Satoimo, Latin: Colocasia esculenta. A starch-rich root-vegetable, popular in Asia, with big heart-shaped leaves.

[15] The currency unit, roepiah (presently spelled as rupiah) was a term used as the equivalence for the gulden.

[16] Cyrtostachys lakka or Cyrtostachys renda. Japanese name; shōjō-yashi, local name; palem merah.

[17] Very likely Samanea Saman (Jacq.) Merrill (local name; kihujan, English name; rain tree, monkey pod, cow tamarind), according to Dr. Dedy Darnaedi, the current director of the Botanical Garden, and his staff, Dra. Ms. Yuzammi, MSc.

[18] From Kojiki (Records of Old Affairs), the first known history book in Japan, compiled in three volumes in 712 A.D., covering the period from the mythical age to the era of the 33rd Emperor, Suiko (628 A.D.). Nintoku was the 16th Emperor who reigned in early 5th C. The name Tonoki is supposed to be that of a river that existed in present-day Takaishi City, to the south of Osaka. Awaji Island and Mt. Takayasu (488m, in Kawachi district) lie some 40km west and at 25km east by north-east of Tonoki, respectively. It is hard to imagine today that shadows could reach such a distance, but it could be possible at that time when the air was unpolluted and absolutely transparent.

[19] A prominent hotel at that time located to the south-west corner of the Botanical Garden, now the site of the Ramayana Theatre (now closed).

[20] Tjisadane (Cisadane). Tji- (Ci-) means ‘water’ in Sundanese. There are a number of names of rivers and places with this same prefix in West Java, such as Tjipanas, Tjiandjoer, etc.

[21] A phrase possibly from an unidentified Chinese classic.

[22] The Zoological Museum.

[23] The author was a prominent hunter and after Java was going to Malaya to hunt for wild game.

[24] Treub started a “visitor’s laboratory” in 1884. The new building opened in 1914 still exists under the name of Treub Laboratorium.

[25] Dr. H. Boschma from the Netherlands. He participated in the 1929 Congress.

[26] Unlike other principal cities in Java, Bandoeng was constructed strategically by Governor-General Herman Willem Daendels in 1810 (officially on 25 October) in a mountain basin when the Regent’s office was moved from Dayeuhkolot (lit. old town in Sundanese), 10km to the south. The population at the time of the author(s visit is assumed to have been about 200,000, whereas it is over two million today. The administration of the Preanger District was moved from Tjiandjoer (Cianjur) in 1864.

[27] A Japanese sweet-snack covered with brown sugar.

[28] The author was comparing the material, not the size. To enjoy the chirp of some kinds of cricket in Japan, some are reared in small cages which are made completely of bamboo.

[29] See, Footnote 121 of Part One

[30] Java has no coal mines. Coal was discovered at Oembilin (Ombilin), West Sumatra in the mid-19th C and production started in 1891. Although the author complained about the fuel, in fact, the railway system in Java itself at that time was the most developed in Asia, rivalled only by Japan and the Korean peninsula (under Japanese rule). Ichizo Kobayashi, Minister of Commerce and Industry, who visited Java for trade talks in 1940 wrote, “The total railway length in Java is 5,400 km, and the average 5,006 m/100 sq. metre is comparable with the 5,008 m/100 sq. metre in Japan. The speed, which covers the distance of 830 km between Batavia and Soerabaja in 12 hours, and the comfortableness and the facilities of the carriages are much superior to those of ours of Tokaido-Line (Kobayashi, Ichizo, I saw the Dutch Indies like this, Tonanshoin, Tokyo 1941)”

[31] The college was the Tokyo Fine Art School (integrated in 1949 into the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music). Miura published the results of his study in: Miura H. (ed.), Genealogy of Javanese Masks, Darumaya-Shoten, Tokyo 1923; Miura H., Javanese Buddhist Remains - Boroboedoer, Boroboedoer Publishing Society, Tokyo 1925.

[32] From the inscription of Karang Tengah (stone monument) studied afterwords, it is believed that Boroboedoer was built during the time of Mahayana-Buddhism Kingdom of Sjailendra, possibly by King Samaratungga in 824 A.D.(?) Boroboedoer may be a shortened version of the name Bhumisanmbharabhudhara, which means a sacred building for worshipping ancestors. The Sjailendra Kingdom was united with the Hindu Kingdom of Sanjaya when Samaratungga’s daughter, Princess Pramodawardhani (Sri Kahulunan) married Prince Rakai Pikatan of the latter sometime in the 9th C. (Casparis, J. G. de, Prasasti Indonesia I, Inscripsi uit de Cailendra-tjid, Djawatan Purbakala R. I., Djakarta 1950; Casparis, J. G. de, Candi, Fungsi dan Pengertiannya, Desertasi Universitas Indonesia, Djakarta 1974. Reviewed by courtesy of Dra. Ekowati Sundari).

[33] According to Prof. Tanakadate who visited Dr. R. W. Bemmelen at the Merapi Observatory in 1942, the latter had established through his geological studies that the area was covered by the mad flow which followed the eruption of 1006 A.D. (Tanakadate, H. The seizure of southern Cultural Institutions, Jidai-Sha, Tokyo 1944). The theory was published in: Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Nederlands Geologisch Mijnbouwkundig Genootschap, Geologische Serie, 20‑36, 1956. As to the move of the court from Matram to East Java by King Mpu Sindok around 928 A.D., the author assumed that the reason was the silting up of the natural harbour, Bergota, at River Garang, located to the north of the kingdom.

[34] The corrosion of these stone arts, viz. by recent acidic rain, is a serious issue. The translator was surprised when he saw in Marquis Tokugawa(s private album that the carvings photographed 80 years ago were astonishingly sharper than they are today. One may also notice the difference, when pictures in old books, e.g., Miura, H., Javanese Buddhist Remains - Boroboedoer, Boroboedoer Publishing Society, Tokyo 1925, and With, Karl, Java - Brahmanische, Buddhistische und Eigenleige Architektur und Plastik auf Java, Filkwang Verlag. M. B. H. Haben 1. W. 1920, are compared with those of today.

[35] More precisely, Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles (1871-1826) who joined Lord Minto on an expedition to Java and acted there as a Lieutenant‑Governor of Java from 1811-15. He was knighted in 1817.

[36] More precisely, Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles (1871-1826) who joined Lord Minto on an expedition to Java and acted there as a Lieutenant‑Governor of Java from 1811-15. He was knighted in 1817.

[37] The first major restoration was carried out in 1907-11 led by Thadeus van Erp. Boroboedoer was restored again in 1970s with modern technology.

[38] The local word is tjandi (candi). The word which is generally used today for religious architecture of pre-Islamic time was originally derived from Chandika, the alias of Hindu Goddess Durga, and meant a grave of kings and nobles and a hall to house a Buddha and Hindu statue (Ishii, Yoneo (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Indonesia, Dōhō-sha Publ. Tokyo 1991).

[39] Stamford Raffles wrote, “The whole structure has the appearance of one solid building, and is about a hundred feet high, independently of the central spire of about twenty feet, which has fallen in. The interior consists of almost entirely of the hill itself. . . .” (Thomas Stamford Raffles, The History of Java Vol. (2), London 1817, quoted in Rush, James R., Java, A Travellers’ Anthology, Oxford University Press, 1996)

[40] According to Dr. Stutterheim, the total number of Buddha statues is 504. The number ― which can be resolved into 8x9x7 or 23x32x7 ― is significant; numerological mysticism has always been cherished subject in Mahayana. (Stutterheim W. F., Studies in Indonesian Archaeology, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, 1956).

[41] It is common to offer flowers with stalks and leaves in Japan

[42] m. parasol, umbrella.

[43] Royal palace, especially of sultans.

[44] These temples represent, as every other Hindu temple does, the heavenly mountain Meru, the residence of the highest Mountain-God, Shiva.

[45] The spelling of the title, “Lala” or “Lolo”, adopted from ancient inscriptions was generally found in old literature, viz. of the Dutch period, whereas the legendary “Rara” is commonly used today as the title of Djonggrang (Jonggrang), even though it does not mean a princess. In the peerage system of Java, viz. Jogjakarta, the title changes in accordance with the generations as follows:

Male; 1. Pangeran (Prince), 2-4. Raden Mas, 5-7. Raden,

Female; 1. Putri (princess), 2-4. Raden Ajoe, 5-7. Rara.

[46] 1790 would be the year when van Boeckholtz discovered the remain of Keraton Boko, 3 km south to Prambanan. C. A. Lons reported on the Prambanan ruin in 1733, probably for the first time. (Subarno, Guide to the Prambanan Temple, Yogya Adv. 1991). Later, Major Hermanus Christiaan Cornelius, who came to Java in 1791, surveyed the Prambanan complex between 1805 and 1807, and made fine drafts and reports which exist to date (Haks, Leo and Maris, Guus, Lexicon of Foreign Artists Who Visualized Indonesia [1600-1950], Archipelago Press, Singapore 2000). He also helped Stanford Raffles uncover the buried and overgrown Boroboedoer.

[47] Conducted by Ir. J. W. Yzerman. The restoration was interrupted during and after the World War II. The Shiva Temple in the middle was first completed in 1953, and others in following years (Subarno, Guide to the Prambanan Temple, Yogya Adv. 1991).

[48] From the inscription on Siwagraha stone monument (856 A.D.), Tjandi Lala Djonggrang is considered to have been built by Rakai Pikatan of Sanjaya Kingdom (Kempers, A. J., Soekmono, Candi-Candi di Sekitar Prambanan, Seri Peninggalan Purbakala III, Penerbit GANACO N. V., Bandung-Jakarta 1974. Reviewed by courtesy of Dra. Ekowati Sundari).

[49] It is said that the blocks were carried off to pave roads and build sugar mills, bridges and railroads, before it was prohibited.

[50] ’Ratoe’ usually means a ‘queen’, but also be used for a king.

[51] There are different versions for this story, viz. how Lala Djonggrang hindered with Dhamarmoyo and gnomes( work (e.g., Subarno, Guide to the Prambanan Temple, Yogya Adv. 1991).

[52] Pawnshops all over the country were monopolised by the government between 1903 and 1917 to protect natives from private business (Torchiana, H. A. van Coenen, Tropical Holland, An Essay on the Birth, Growth and Development of Popular Government in an Oriental Possession, University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1921). The pawnshops still operate today.

[53] Lit. beautiful garden. Local elderly people say that the castle was still surrounded by flower gardens several decades ago.

[54] Perhaps, the author had got wrong information. The architect is said to be Kjahi Toemenggoeng Mangoen di Poera. The ornamental motives are Javanese ones, but the architect has also applied his knowledge of European architecture (Stutterheim, W. F., Pictoral history of civilization in Java. Translated by Mrs. A. c. de Winter‑Keen, The Java-Institute and G. Kolff & Co., Weltevreden, 1926).

[55] The author might have been familiar with Arthur Conan Doyle’s “Sherlock Holmes” and Maurice Leblanc’s “Arsene Lupin”.

[56] In actual fact, the palace was damaged by an earthquake which hit the area in 1865. Dr. Stutterheim wrote in 1926 that restoration of the building would be of no use on account of its inferior masonry (Stutterheim, Stutterheim, W. F., Pictoral history of civilization in Java. Translated by Mrs. A. c. de Winter‑Keen, The Java-Institute and G. Kolff & Co., Weltevreden, 1926).

[57] The first line of a Chinese poem entitled (A Spring View( by Do Fu (712-770), of the Tang Dynasty. The second line follows:

“The castle is in the spring, and grasses and trees are dense”.

[58] One of the trees on the left-hand side (as seen from the palace) died just before Sultan Hamengkoe Boeono IX passed away in 1988, and was replaced with a young tree.

[59] It changes on the lunar calendar. The Javanese calendar was originally based on the solar system but the Islamic, lunar system, having ca. 354 days a year, was first introduced on the first day of the first month in 1555 (8 July 1663).

[60] The author used a word ‘Hatamoto’ which means those who were the direct vassals of the Shogun in the Tokugawa Era Japan (1600-1868).

[61] The hero in a historical drama, “Kokusenya-gassen (Coxinga(s battle)”, written for joururi (a Japanese traditional puppet-show) by Monzaemon Chikamatsu and first played in 1715, in which Watōnai, alias Tei-Seikō (c. Ch’ eng‑koeng), born of a Chinese father and a Japanese mother, fought against Qing to revive the Ming dynasty, being given the surname of the Ming Emperor and called by an honourable title, Kokusenya (Coxinga). Having been unsuccessful in that attempt, he retreated to Taiwan with his followers, defeating the Dutch at Fort Provintia and Fort Zeelandia in 1621-1622. It is probable that the words ‘one hundred years’ in the Japanese text was a misprint of ‘three hundred years’.

[62] Later called the First World War (1914-18).

[63] An irony. The author may be commenting about himself.

[64] A literatory phrase which often appears in Japanese classic literatures but its origin is unknown to the translator.

[65] A line to praise the beauty of Lady Yang Kuei‑fei in a long poem, “Song of Everlasting Sorrow”, written by Po Chu‑i (772‑846) about the fate of Tang Emperor Hsuan Tsung (685‑762).

[66] Meiji Restoration (1868) when the Shogunate Regime ended and the modernisation of Japan started.