The idea to entrust the king of beast, lion, with the guarding of shrine occurred in ancient times as a sculpture of lion to protect Ishtar, Assyrian goddess of love and war affairs, is held in British Museum and six lion statues to guard Apollo remains in the Lion Terrace in Delos Island in the Aegean sea. The adoption of lion statue in Buddhist temples is allegedly originated in Gandhara, as the imitation of Hercules for dvarapala was, as some photographs are found on the Internet.

Left: Guardian lion (one of the pair) from the entrance to the Temple of Ishtar adjoining the palace of King Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883-859 BC) of Assyria. A collection of British Museum. Photographed by M. Iguchi, April 2017. (Added in March 2019)

Right: Lion statues at Butkara Stupa, Swat, Gandhara. The stupa was presumably erected in the era of King Asoka (ca. 268-232 BC).

http://tabi70.pro.tok2.com/tabi/paki/paki10.htm. (No contact of the image owner available.)

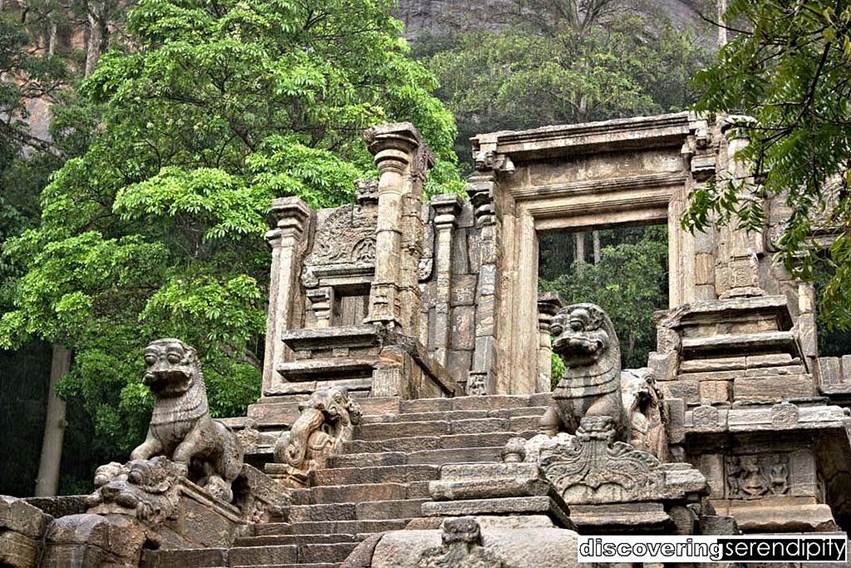

Lion statues as the gatekeeper of temples spread around India. In Sri Lanka in particular, they are placed in Abhayagiri Dagoba in Anuradhapura, the old capital lasted until the invasion of Chola in the 11th century, and Kiri Vihara in Polonnaruwa, the new capital of Sinhala dynasty revived in the late 12th century. Also, pictures of lion statues set at the Yapahuwa in a pair, like Shishi-komainu statues in Japan, are found in the Internet. For reference, Sri Lanka is strongly connected to lion, as the Sinhalese who share the majority of population of the country etymologically means “lion people” and a lion is depicted in the flag of the present-day Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.

Lion statues from Mathura, Kushan.

Left and Middle: 1st c., Mathura National Museum.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Half_Engaged_Lion_Standing_with_His_Mouth_Open_-_Circa_1st_Century_CE_-_ACCN_0-2_-_Government_Museum_-_Mathura_2013-02-24_6646.JPG; http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lion_-_Kushan_Period_-_ACCN_00-04_-_Government_Museum_-_Mathura_2013-02-24_5884.JPG.

Right: 2nd c., Cleveland Museum.

http://ignca.nic.in/asp/showbig.asp?projid=ac25.

Left: A lion relief in Anuradhapura, the old capital of Sri Lanka.

http://www.flickriver.com/photos/chintaka/tags/anuradhapura/

Right: A lion statue at the entrance of Polonnaruwa Audience Hall, Sri Lanka, 11-13th c.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Polonaruwa,_lion_Audience_Hall%28js%29.jpg

A pair of lion statues at Yapahuwa Castle, Sri Lanka, 13th c.

http://legacy-site.lasith.lk/historical/pre-colonial-era/yapahuwa-rock-fortress/. (No contact of the image owner available.)

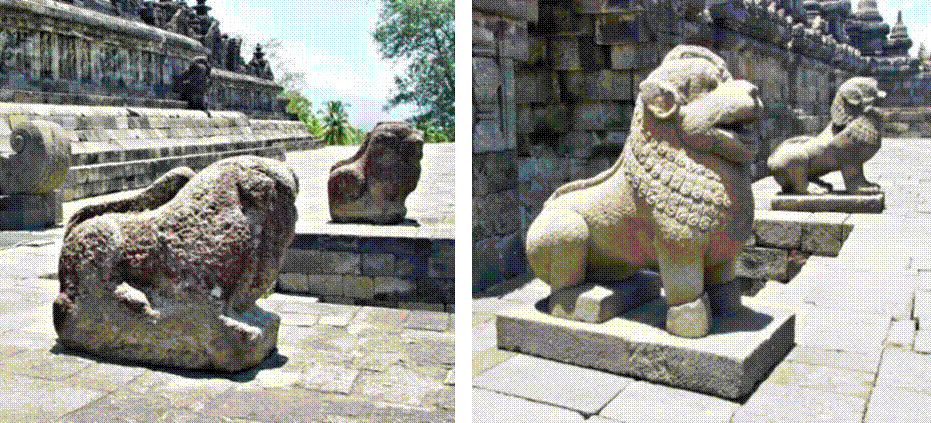

Although a number of Buddhist temples remain in Java, Lion statues exist only in Candi Borobudur, as far as I have seen. There, lion statues are placed not only at the foot of staircases from the ground but also in the upper, square and circular layers.

The lion statues placed on the ground in the east side on the extension of the main approach had a charming countenance rather than an intimidating air. Their eyes are round, as those of “Jungle Emperor Leo” in the cartoon book of Osamu Tezuka, their cheeks were plump and their manes stood upright like those of donkeys.

A lion statue at the ground at the east side staircase, Borobudur. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

The lion statues in the south side looked to have a faces which are more similar to that of the real animal, although they are significantly eroded, but their main also resemble those of donkeys. The statues in the west side were more or less similar to those in the south side but they were not threatening, hanging their head down. The lion statues on upper layers were almost similar to those on the ground of south side, although they were different in details. One may regard the south-side lion statues are the representative type in Borobudur.

A pair of lion statues at the south side staircase, Borobudur. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Left: A pair of lion statues at the west side staircase, Borobudur. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Right: Lion statues by the staircase on the First Layer, Borobudur. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Lion statues on the Top Layer, Borobudur. Left and Right, photographed by M. Iguchi, in February 2015 and February 2007, respectively.

After visiting Candi Borobudur several times, I realised that the feature of lion statue in this temple looked similar to those in Sri Lanka. Indeed, Rev. Gunadharma, the legendary architect of Borobudur, is said to have come from Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka, encountered Princess Pramodawardhani of the Sailendras and been asked to design Candi Borobudur from her father, King Samaratungga[1]. It would not be unreasonable to imagine that he drew pictures of Sri Lanka’s traditional lion statue and showed them to the artists in Java.

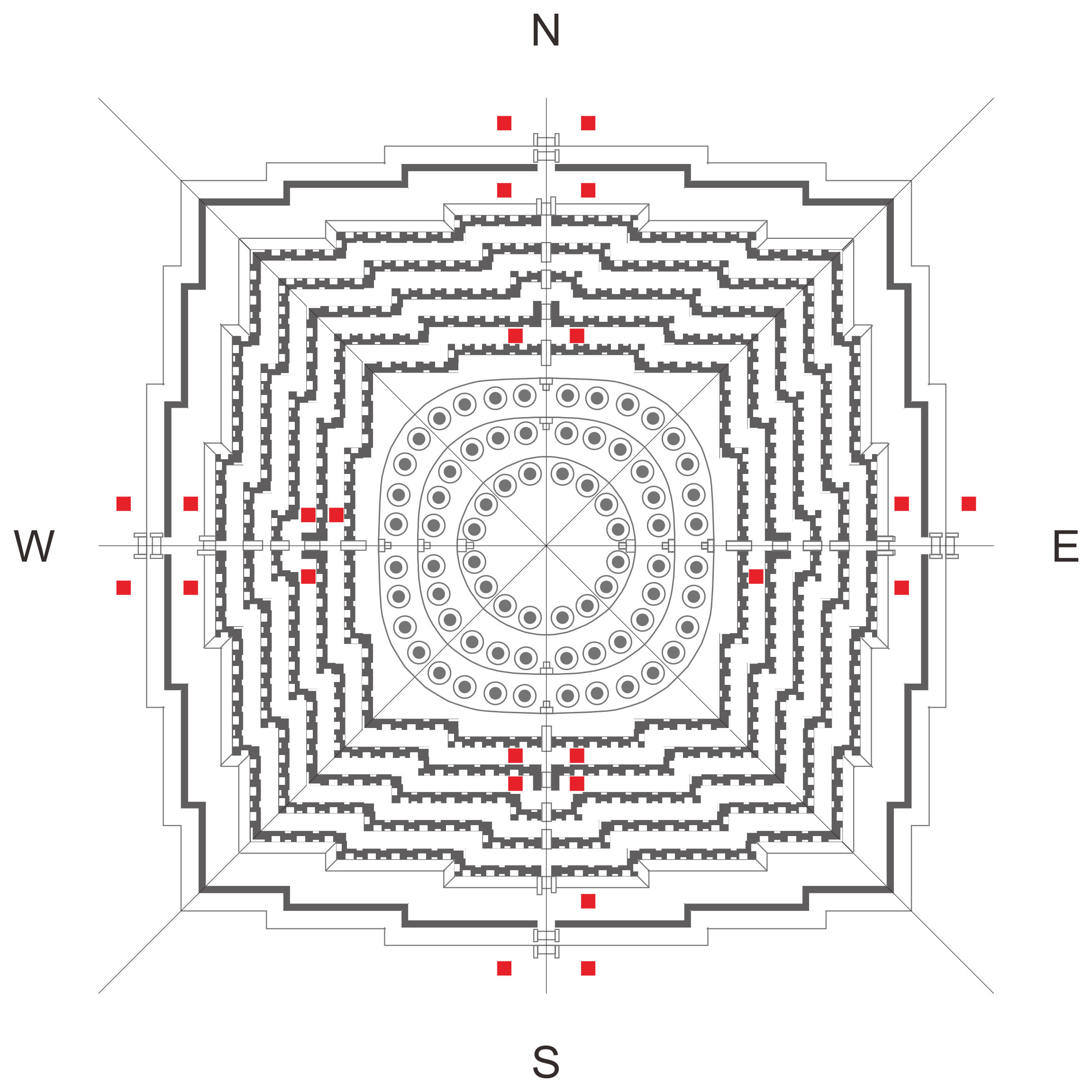

The fact that the design of lion statues at Borobudur is irregular implies that they were not produced simultaneously. Having realized also that the placement of the statues at the side of stairs of four sectors were not the same, a survey was conducted during the recent visit (June 2019), helped by a friend of mine who accompanied me, as the result is show below. Although the possibility that some which had originally been installed became extinct in later times is undeniable, it could also be possible that the placement was sporadic from the beginning.

The placement of lion statues (Red marks) at Candi Borobudur. Surveyed June 2019.

Then, why lion statues do not exist in other temples in Java? The reason may due to the fact that Javanese people were unfamiliar with lions, as the inhabitation area spread from Africa up to Balkan Peninsula westward and up to Caucasus northward but up to India eastward in Asia.

It was not the kind of thing placed as the gatekeeper of a temple, but a sculpture of lion similar to that of Borobudur or Sri Lanka was found in the so-called “Prambanan Motif” adorned on the walls of basement of Candi Siva and Candi Nandi in the Candi Loro Jonggrang Complex, constructed by Rakai Pikatan of Sanjaya Kingdom in 856 AD. I would just imagine that the lion sculpture was sculpted by the same artist group who had participated in the construction of Borobudur about 30 years ago, although the meaning of the whole motif had not been well interpreted.

One of the Prambanan Motifs with a lion in the middle. The animals under the tree on the left- and right-hand side are various. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

As an appendix, modern gold-plated lion statues depicting the real lions, which I saw recently (June 2019) at Mangkbumi Palace in Surakarta (Solo) are shown below.

Gold-plated true-to-life lion statues at the Mangkbumi Palace in Surakarta (Solo). Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (New).

The oldest lion statues in Japan are the pair of pieces in the Great South Gate of Todaiji Temple, the one on the west side and the other on the east side measuring 1.8 and 1.6 metres tall, respectively, both placed on the 1.4 metres tall pedestals. According to the history, these stone statues were sculpted by four artists visited from South Sung with the stone imported from Ningbo[2]. The figure of the lions depicted the ingenuous Chinese lions wearing a bit of smile, standing on the pedestal with exotic inscriptions, unlike many guardian dogs produced later until the modern time. At that time, monks and merchants travelled back and for the between Japan and China as evidences remain in Nara, although there were no official relationship and hence no exchange of ambassadors.

Statues of Chinese Lions at Todaiji Temple, Nara. Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2014.

The so called Shishi-komainu (lit. lion and dog), consisting of an open-mouth lion and a closed mouth dog emerged in the Heian Period (794-1185/1192 AD), and became more popular in later years, being adopted not only in temples but also shrines. Stone-made lion gatekeepers were rather rare in early days as wood was more popular as the material.

Wooden lion statues at Daihou Shrine, Ritto, Shiga Prefecture. Held at Kyoto National Museum.

http://www.kyohaku.go.jp/jp/syuzou/meihin/choukoku/item09.html

Shishi-komainu (lion-dog) statues in Toji Temple, Kyoto.

http://www.kyohaku.go.jp/jp/dictio/choukoku/komainu.html.

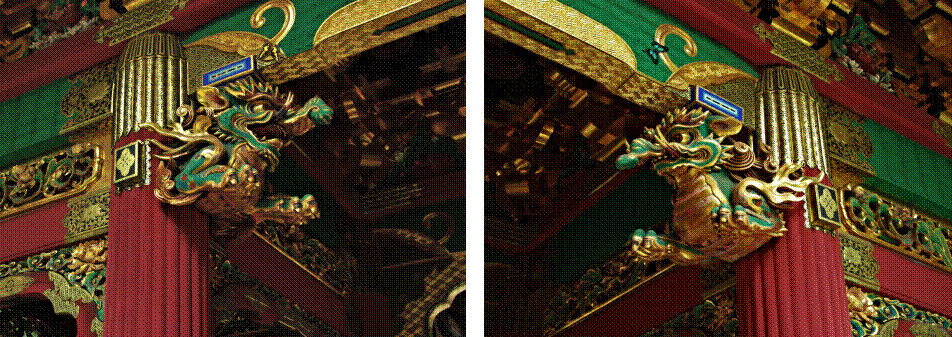

Shishi-komainu (lion-dog) statues at the rear side of Youmei Gate, Toshogu Shrine, Nikko. They were sculpted (probably) by Kouon Hougen based on the colour picture drawn by Yosen Kanou[3] in Kwanei Era (1624-25 AD). Photographed by M. Iguchi, August 2014.

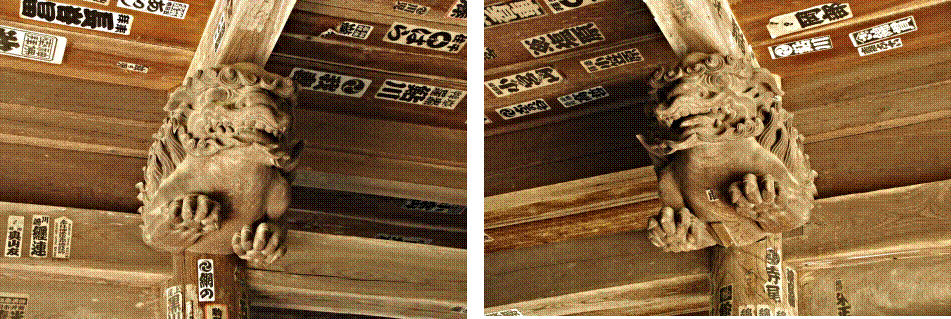

Shishi-komainu (lion-dog) statues at the rear-side of Nioumon Gate of Higashi-Kouyasan Iouji Temple, Kanuma, Tochigi Prefecture. Made of copper in 1992 by Mr. Kenjiro Sato[4].

Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2016.

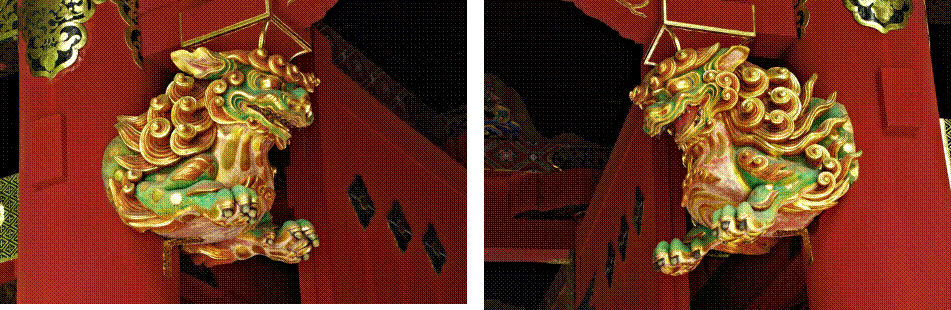

When I visited Daiyu-in Temple, the mausoleum of the 3rd Shogun Iyemitsu Tokugawa, in Nikko, I saw the carvings of Chinese Lions, sitting with their forefeet folded, at the Nioumon Gate and the Yashamon Gate. They were coloured in gold, read and green like the gates themselves.

Chinese lions at Nitenmon Gate.

Chinese lions at Yashamon Gate

Carvings of Chinese lions at the gates of Daiyuin Temple, Nikko.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, July 2015

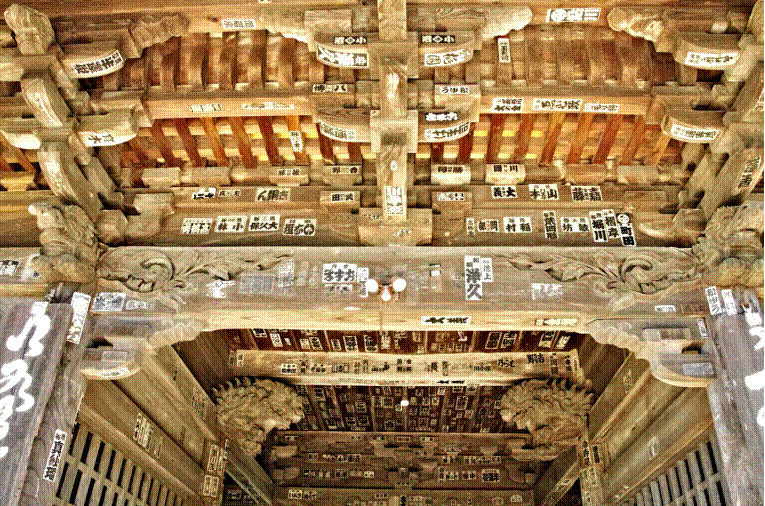

Similar carvings were found also at the front gate of Kashiwawosan-Daizenji Temple in Yamanashi Prefecture. Whilst the figure of the Chinese lions under the ceiling of the central space were normal, the lions at the left- and right-side ends of the front beam and those under the eaves at the four corners of the building had a long nose like that of an elephant. I looked at pictures taken at the Daiyuin-Temple at Nikko and realised that those lions at Yashamon Gate also had a long nose.

The front gate of Daizenji Temple was first donated in the 17th year of Genroku Era (1746 AD) by the Doi Family, a former vassal of the Takeda Family who were pardoned by Iyeyashu Tokugawa after the defeat of the Takeda and made the lord of Tsuchiura Castle in Hitachi (the present-day Ibaraki Prefecture). Although the present gate is new rebuilt in the 17th year of Kwansei Era (1798) after a fire, not only the architecture of the gate but also the attached ornaments apparently inherits the original design of the early Edo Period. Then, it is not surprising that the present lion carvings resemble those in the Daiyuin Temple in Nikko.

A view of the upper part of the main gate. Pairs of lions are seen under the ceiling of the central spase and at the left- and right-ends of the front beam.

Chinese lions under the ceiling of the central space.

Left: Chinese lion at the left-end of front beam. The one at the right-hand side looked the same.

Right: The Chinese lions at one of the four corners under the eave. Those at three other corners looked the same. Wood carved Chinese lions at the main gate of Kashiwawosan-Daizenji Temple, Katsunuma, Yamanashi Prefecture.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, October 2015.

According to literature[5], beam-end decorations imagining Chinese lions, called shishi-bana emerged after the Kamakura Period and the sculptures with a long nose was named baku-bana (lit. tapir beam-end). In an comprehensive Internet article[6], it is explained that the baku in this case is not real tapir but an imaginary and composite creature that have the trunk and tusks of an elephant, the eyes of a rhinoceros, the tail of a cow and the paws of a tiger from Chinese mythology in which the animal was thought to prevent or devour nightmares.

In Hindu mythology, a lion with an elephant’s nose called Gajasingha (lit. elephant-tiger) is popular as adopted, for example, in the royal emblem of Cambodia on the left-hand side along with a normal lion drawn on the other side. I suppose that the Chinese baku must have been derived from the Indian Gajasingha.

Although the source of the myth is unknown to me, Gajasingha seems to symbolise the strength of lion and the endurance or softness of elephant[7], [8].

The function of shishi-bana and baku-bana attached to the beams of temples must be to watch intruders, just as Shishi-komainu statues.

I have remembered one of the four lion sculptures with a long nose, being placed underneath the eaves of the first roof of the Golden Hall of Horyuji Temple, Kyoto, viz. at the northeast corner, that was not mentioned in “The Atlas” section”. Since the body looked like a Chinese lion, it would be supposed to have its origin in the mythical baku of China.

A sculpture of lion with a long nose underneath the eaves at the northeast corner of first floor roof of the Golden Hall of Horyuji Temple, Nara.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2015.

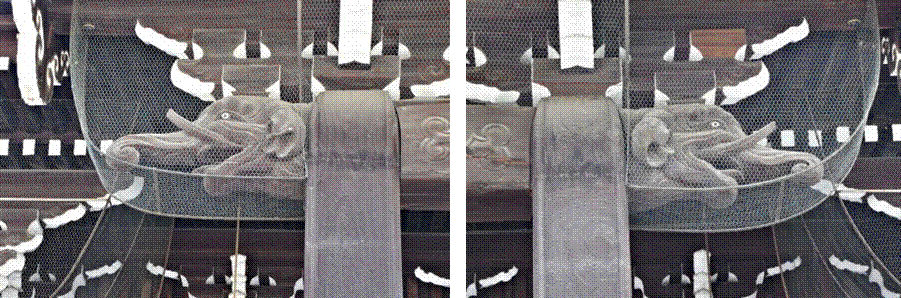

With respect to wrestler-type sculptures by a Master Sculptor, Jingoro Hidari, placed underneath the eave of the Founder’s Hall of Shoshazan Kaizando in Himeji, Hyogo Prefecture, mentions were given in “2. The Atlas that supports buildings”. In the same Hall, sculptures of Shishi-bana allegedly carved by the same sculptor were also found at the both ends of the front beam. The feature of lions, viz. face, body shape and curled hair, observed in photographs taken with a telescopic lens, I remembered the sculptures at the Nitenmon Gate of Taiyuin in Rinnouji Temple, Nikko. In Nikko, A sculpture of “Sleeping cat” placed above the entrance of Toshogu Shrine is famous as a work of Jingoro Hidari. Since he was a master carver who participated in the construction of the shrine[9], I supposed the Shishi-bana and other sculptures were also worked by Jingoro Hidari or members of his school.

Southeast beam-end. Northeast beam-end.

Shishi-bana at the Founder’s Hall of Shoshazan Kaizando, Himeji.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2016.

Shishi-bana and Baku-bana were found in many other temples and shrines. Two examples are shown below.

Shishi-bana at the Worship Hall of Haguroyama Shrine, Kamikawachi, Utsunomiya. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2016.

Shishi-bana and Baku-bana at the Golden Hall of Higashi-Kouyasan Iouji Temple, Kanuma, Tochigi Prefecture. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2016.

At the ends of the entrance beam of the Founder’s Hall (Goei-do) and the Amitabha Hall (Amida-do) of Nishi-Honganji Temple in Shimogyo, Kyoto, rebuilt in the 13th Year of Kwan-ei (1636 AD) and the 10th Year of Houreki (1760), respectively, I saw a pair of ornaments which may be called Zou-bana (lit. Elephant’s nose) and Baku-bana) which, unlike those at the gates of Taiyuan Temple in Nikko and Kashiwawosan Daizenji Temple in Yamanashi Prefecture, depicted only the head part of animals. Whilst the sculpture at the Amitabha Hall might be the expression of an imaginary baku, the one at the Founder’s Hall looked very similar to the head of real elephant. Since an elephant which was brought from Annam to Japan in 1727 is recorded to have passed Kyoto before sent to Edo (the present-day Tokyo), I suppose the sculptor had witnessed the real animal.

Left. Right

Baku-bana at the beam of entrance of Amitabha Hall (Amida-do), Nishi-Honganji Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2016.

Left. Right

Shishi-bana at the beam of entrance of Founder’s Hall (Goei-do), Nishi-Honganji Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2016.

[1] According to a tradition, “She [Pramodawardhani] lead the mission to finish Borobudur temple, and also lead the mission to find Gunadharma, architect of Borobudur” http://transbonja.deviantart.com/art/Queen-Pramodawardhani-55410856. The present writer regret that he must have read more detailed article about this tradition but cannot remember.

[2] 奈良県民だより 平成22年8月号. (Nara Prefecture Letter, August 2010).

[3] 日光東照宮社務所 『日光東照宮百話』,日光東照宮社務所,1925 (Nikko-Toshogu Office, “One hundred tales for Nikko-Toshogu, Nikko-Toshogu Office 1925).

[4] The statues were sculptured by Mr. Kenjiro Sato, a local sculptor, and dedicated by Mr. Fumio Fukushima, the chief believer of the Temple. (Private letter fro m The Cultural Assets Section, Kanuma City.)

[5] 近藤 豊,『古建築の細部意匠』,大河出版 1972 (Yutaka Kondo, Detailed design of ancient architecture, Taiga Shuppan 1972).

[6] Mark Schumacher, “A to Z Photo Dictionary of Japanese Buddhist Statues”. http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/buddhism.shtml

Folk-lore (India). Vol. 18-19 p.357 1977 (Google eBooks)

[7] Arts of Asia, Vol. 38, Arts of Asia Publications, 2008 (Google eBooks)

[8] Folk-lore (India). Vol. 18-19 p.357 1977 (Google eBooks)

[9] 左光挙著,『名工左甚五郎の一生 』,新人物往来社 1971 (Koukyo Hidari, The life of Jingoro Hidari, The Master Sculptor, Shin-Jinbutsuouraisha 1971).