(5) Statues of wild

boars, tigers, mice and foxes at temples and shrines in Japan

In temples and shrine sin Japan, we often see statues of wild boars, tigers,

mice and foxes which are placed like Shishi-komainu guardian statues.

Wild boar statues

The kind of shrines where wild boar statues are found are the ones which deify

Wake-no-Kiyomaro (or Kiyomaro of Wake,

和氣淸麻呂, 733-799), the most famous one being Goou-jinja Shrine (護王神社),

located in front of the Hamaguri-Gomon (Gate) of the Imperial Palace,

Kyoto.

Front view of Goou-jinja Shrine. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 10 October 2018.

The origin of Goou-jinja is said to have been a shrine for Gohouzenshin (護法善神, heavenly gods who protect Buddha and Buddhists) which was built after the death of Wake-no-Kiyomaro to enshrine his soul in the precinct of Jingoji Temple (神護寺) which had been founded in 781 AD by Kiyomaro himself at Mt. Takao in north-west Kyoto.[1] In 1851 in the late Edo Period, Kiyomaro was granted the Fist Senior Rank (正1位) and the title of Goou-Daimyojin (護王大明神) by Emperor Koumei (孝明天皇) who praised his historical deeds. In 1866 (the 7th year of Meiji) the Gohouzenshin Shrine was renamed as Goou-jinja Shrine, being ranked as Imperial Shrine of Special Status. In 1886 (the 19th year of Meiji), by the order of Emperor Meiji, new shrine was constructed at the present site and the deity was moved there from Mt. Takao. Princess Wake-no-Hiromushi (和氣廣虫), elder sister of Kiyomaro, was also deified.[2] The legends of “Plot of Usa Hachiman Shrine Oracle” in which Kiyomaro and wild boars were related were written in Nihonkouki, Shoku-Nihonki, etc.[3]

It was in the Heian Period

when Wake-no-Kiyomaro and his sister, Mushimaro, came from Bizen Province (a

part of the present-day Okayama Prefecture) to serve for Empress Kouken (孝謙天皇,

reigned from 749-758). The Empress had once abdicated the throne but ascended

the throne again as Empress Shotoku (稱徳天皇)

in 764

(until 770) after the suppression of Abe-no-Nakamaro’s revolt. In 769, a

Buddhist Monk, named Doukyo (道鏡),

who had risen to power and became the Highest Monk under the favour of the

Empress, received a divine revelation, via the priest of Dazaifu Shrine, which

said that “If Doukyo is made ascend the throne, then peace will reign in the

country.” He was certainly delighted. The Empress invited Kiyomaro and told, “In

a dream, a messenger from the Hachiman Shrine emerged and said, ‘The god demands

Mushimaro to be sent to Usa to receive his will.’ Since she is not strong enough

to travel the distance, you shall go there instead of Mushimaro.” When Kiyomaro

prayed at Usa in front of the shrine, a 30 feet tall figure that shone like a

full moon suddenly appeared and told, “Ever since the creation of this nation,

the sovereign and subject has strictly distinguished. No subject became

sovereign. The imperial line must be continuous. Doukyo is irrational,

arrogantly wants the sacred imperial treasures. An outlaw must be eliminated.”

When Kiyomaro reported this to the Empress, Doukyo in anger made Kiyomaro and

Hiromushi exiled to Oosumi and Bingo Provinces, respectively. Next year when

Empress Shotoku passed away and the throne was succeeded by Emperor Kounin (光仁天皇,

reigned 770-781),

Doukyo who lost the support was exiled to Shimotsuke Province. Kiyomaro and

Hiromushi were called back to the capital to serve for the government again.

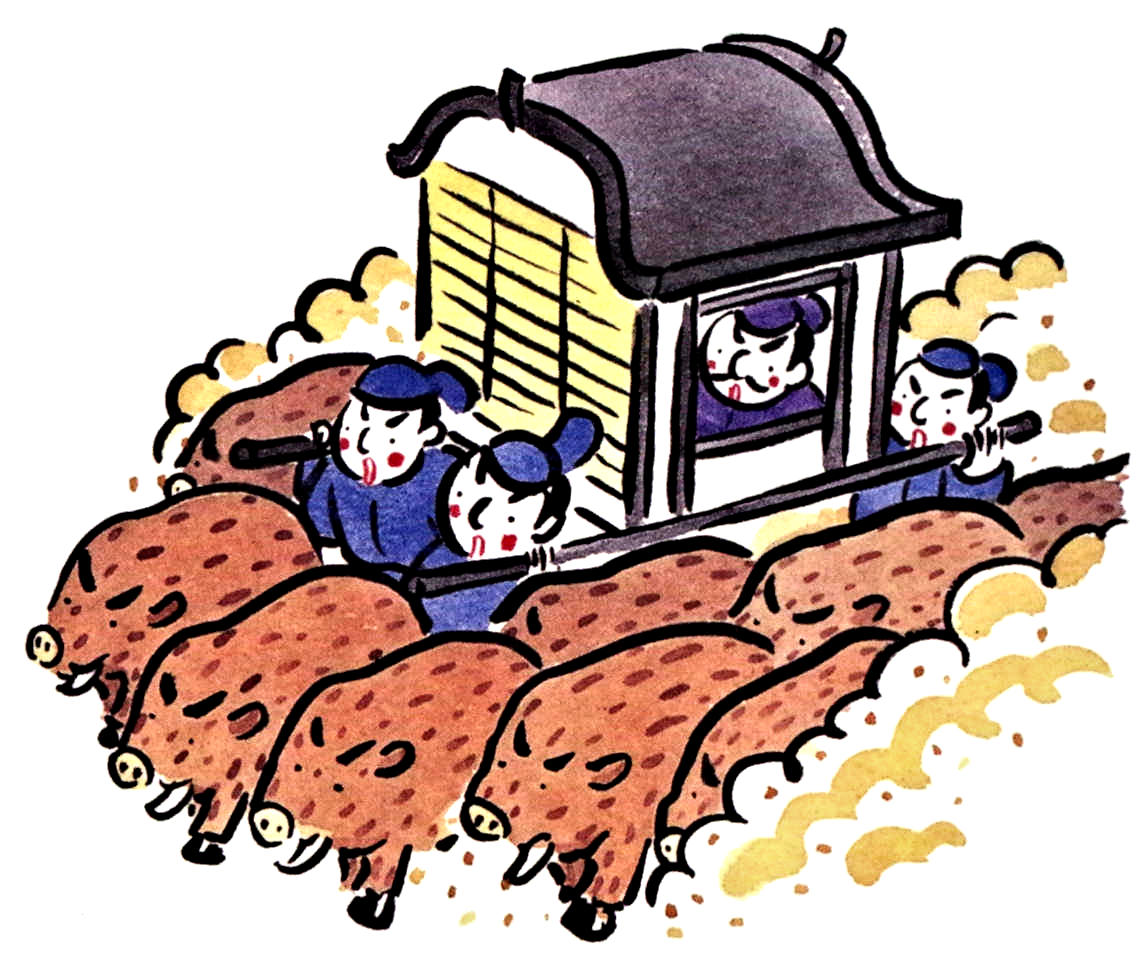

Wild boars appeared during Kiyomaro’s travel to Oosumi Province. It was briefly

written in Nihonkouki

but in detail in the

Legends of the loyal Wake-no-Kiyomaro (和氣淸麻呂忠義傳,

Wake-no-kiyomaro chugi den).[4]

“Doukyo cut the legs of Kiyomaro who was leaving from the capital. He tried to

assassinate him at Mt. Ikoma in vain as a sudden thunderstorm obstructed the

view and imperial soldiers came. On his way to Oosumi, Kiyomaro planned to drop

at Usa Shrine to thank for the god’s will: It was when he came to Wakata

Village, Usa District, Buzen Province, that some 300 wild boars emerged to

protect him and escorted his palanquin about ten ri (ca. 40 km), before they

disappeared into the forest. As soon as Kiyomaro prayed to the god, his wounds

were healed and he was able to return on

horseback.”

In the Legends of loyal Wake-no-Kiyomaro,

it was also written that the Empress Shotoku’s despatch of the young

Wake-no-Kiyomaro of thirty-five years old as an envoy to Usa Hachiman Shrine

would have been recommended by Kibi-no-Makibi (吉備眞備), a senior advisor, who served the Empress ever since she was

Princess Abe.

Wild boars protecting Wake-no-Kiyomaro’s palanquin (from a panel in Goou-jinja

Shrine)

What was the true figure of the wild boars? The conjecture that

they would have been the soldiers of a local lord who was loyal to the imperial

court[5]

was interesting to read.

In Goou-jinja Shrine, pairs of Shishi-komainu-like wild boar statues exist in

front of the main gate and the warship hall, the inauguration date of which

being the 23rd year of Meiji (1890) and the 18th year of Heisei (2006),

respectively. There were several more single statues in the shrine’s yard.

Wild boar statues in front of the main gate (left) and the hall of Goou-jinja

Shrine. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 6 November 2018.

Wild boar statues in Goou-jinja Shrine. From the left: Side of the main gate,

hand-wash basin at the hall, hand-wash basin at the rear of the hall, front of

the holy tree. Photographed by M. I. 6 November 2018.

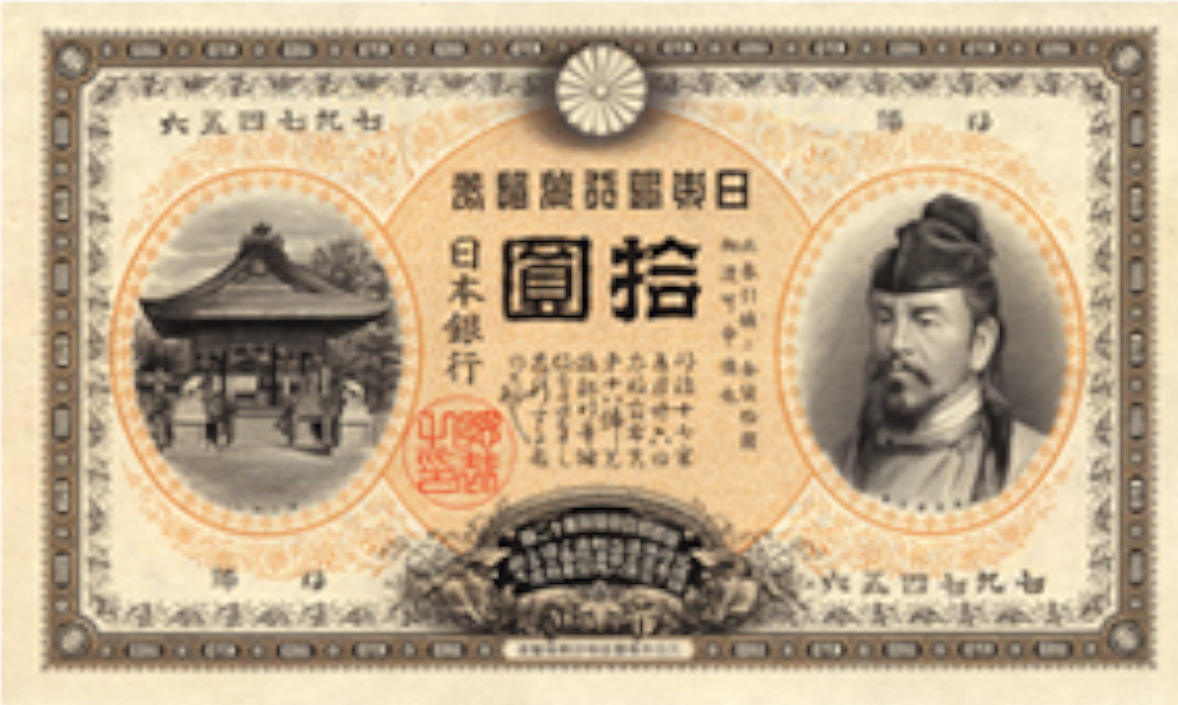

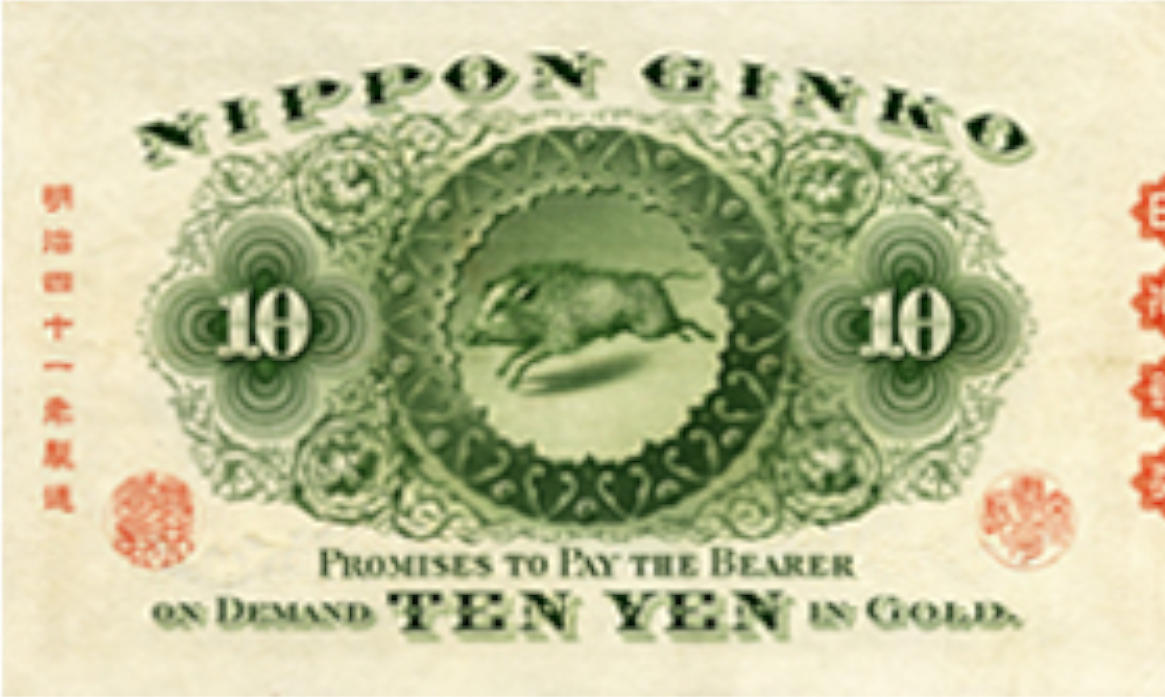

For reference, the hall of Goou-jinja Shrine and the portrait of

Wake-no-Kiyomaro were depicted on the Ten Yen Convertible Note issued by the

Bank of Japan in 1899 and circulated until 1939. The note was nicknamed Ura

Inoshishi (lit. Rear wild boar) because on the rear side was a picture of a wild

boar. The present writer remembers he saw an expired note in his childhood at

his uncle’s house.

Ten Yen Convertible Note issued by the Bank of Japan. https://www.npb.go.jp/ja/museum/tenji/gallery/ura-inosisi.html

Wake Shrines which worship Wake-no-Kiyomaro exists also in Wake Town, Okayama

Prefecture, and in Shukukubota, Makizono Town, Kirishima City, Kagoshima

Prefecture. The former is considered to have been founded long time ago as the

shrine of Wake family by Otohikoou

(弟彦王, a great-grandson of Nuteshiwake-no-mikoto (鐸石別命,

a son of Emperor Suinin, 4th century) who is said to have settled in this

district. This shrine which enshrines Otohikoou and his descendants, including

Kiyomaro and Hiromushi was ranked as the Prefectural Shrine in 1919. The

present hall was built in Meiji Era. The wild boar statues are rather new, built

in the Heisei Era, according to Internet articles.

The site of the shrine in Kirishima City was identified in 1853 by Lord

Nariakira Shimadzu of Kagoshima Clan as the place where Kiyomaro was exiled. The

foundation of the shrine was petitioned in 1939 and the construction commenced

in 1943 but completed after the War in 1946. In photographs in the Internet,

wild boar statues seem to exist not only in front of the hall but also on the

approach, although the details are not certain for the present author.

Left: Wake Shrine at Wake Town, Okayama Prefecture.

Right: Wake Shrine at Kirishima City, Kagoshima Prefecture.

http://kirishimakankou.com/guide/2013/06/post-62.html.

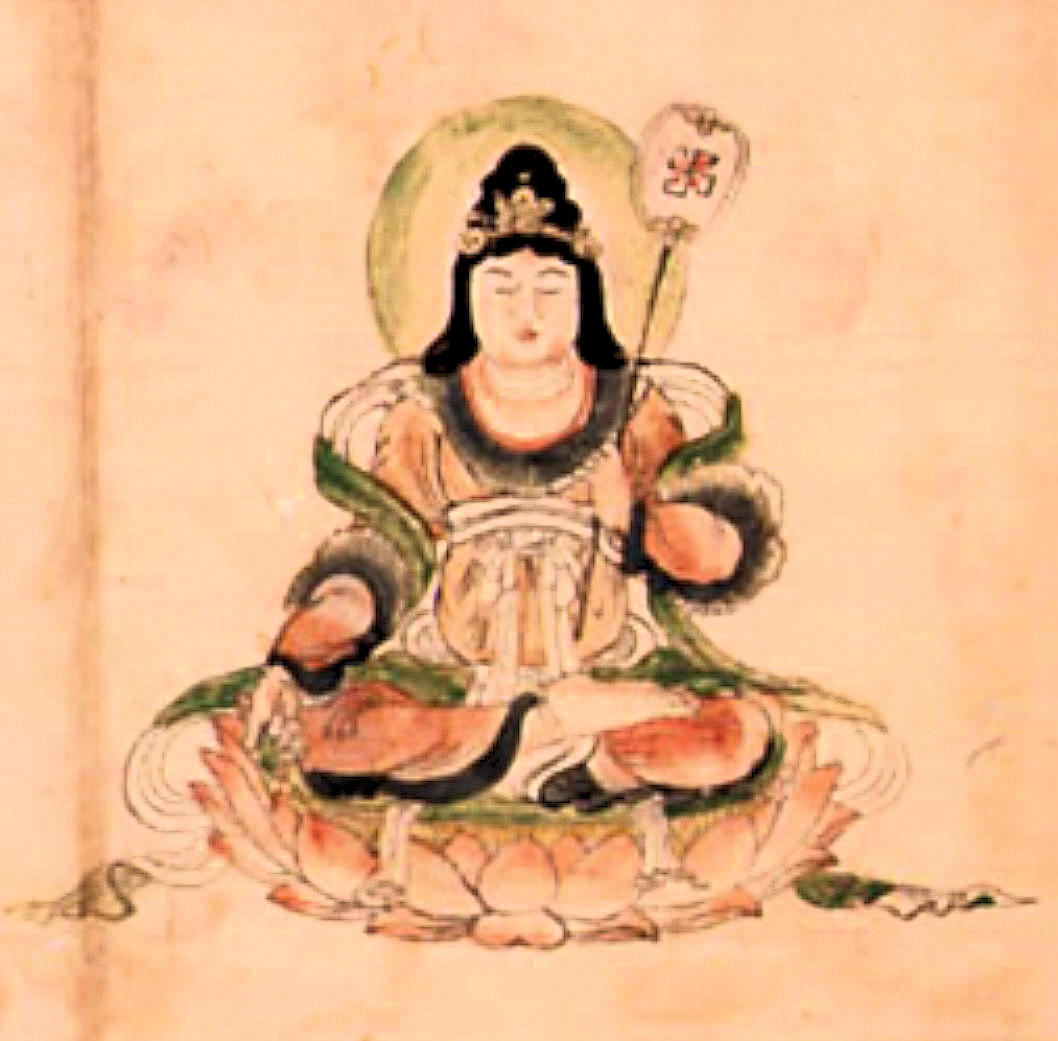

Wild boar statues in temples relates to Marishiten, a god of ancient Indian

origin, Marīcī,

which is the deified form of heat haze. According to the

Buddhabhashita

Marici Bodhisattva Sutra (佛説摩利支天經)[6],

“He has a supernatural divine power, he always goes with the sun, the sun and

moon cannot see him but he can see the sun. Man can neither see him, notice him,

grasp him, seize him nor hurt him.” Since Marici is such an insubstantial entity

that can never be injured or arrested, he was worshiped by warriors. The sutra

also told the details for making figure of Marishiten as follows. “The figure

should be similar to that of a nymph. Her height should be half a sun (ca. 3 cm)

or one sun but less than two suns. She stands or sits on a lotus flower. Her

crown, necklace and other accessories are elegant and must be neat. She has a

fan in her hand which is similar to that of a nymph in front of Vimalakirti. Her

right hand forms the Varada-mudra (wish-granting mudra). If you make such a

figure and put it on your head or back or in your clothes, then due to the

supernatural divine power you shall never meet a disaster and, in the place of

your enemy, you shall win...”.[6a] Thus, it is

said such warlords as Masashige Kusunoki and Toshiie Maeda put a small

Marishiten figure in their helmet before they went to the front.

The relation of Marishiten and wild boar is written in the Great Marici

Bodhisattva Sutra (大摩里支菩薩經). In this case, “Marici has three faces and six arms. Three

faces express angriness, Bodhisattva and a female child. Six hands hold such

weapons as a bow, arrows, needles, wire, hooks, traps and truncheon, whereas the

nymph-like figure has only one fan in one of the two hands. He rides on the back

of a wild boar.”[7a]

Among paintings and sculptures are some variation, ones with eight-arms, ones on

a group of seven wild boars, etc.

Left and Middle: Nymph-like and Three-face-five-arm Marishiten pictures. Duplicated from the homepage of Kouyasan holy treasure house, http://www.reihokan.or.jp/syuzohin/hotoke/ten/marishi.html.

Right: Marishiten painted on the basis of Hokusai Katsushika Manga

(illustrations), Duplicated from:

https://www.ensenji.or.jp/blog/2478/.

Statues of wild boar found in front of the gate or in the precinct have no

Marishiten on their back. This is considered not unreasonable as Marici is

originally invisible.

Among sub-temples of Kenninji Temple (Rinzai Sect of Zen Buddhism) is Zenkyoan

Temple, dedicated to Marishiten, which was founded in 1333 by Rev.

Daikansei-Sessho (大鑑淸拙正澄) from Fujian, China. The principal image has three faces and 6

arms and sits on a group of seven wild boars. Beside various common arms he has

a wheel-like object behind his head, which must be a sudarshan chakra, i.e., a

kind of discus weapon with 108 edges.

Four pairs of wild boar statues are placed in front of the hall, at the side of

the approach from the main gate (south gate), in front of the west gate and at

the side of the approach from the west gate. In addition, single wild boar

statues were also found at the west approach and at the hand-wash basin. The

design of the wild boar is various, some of the looked ferocious and some

others, charming.

The main gate (Left) and the west gate (right) of

Zenkyoan Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 6 November 2018.

Left: The main hall of Zenkyoan Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 6 November

2018.

Right: The three-face-six-arm Marishiten statue of Zenkyoan

Temple. Duplicated from the homepage of the temple,

http://zenkyoan.jp/about_marishiten/#c02.

Wild boar statues in front of the main hall (Left) and at the south approach of

Zenkyoan Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 6 November 2018.

Wild boar statues in front of the main hall (Left) and at the south approach of

Zenkyoan Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 6 November 2018.

Wild boar statues by the side of west approach (left) and at the hand-wash basin

of Zenkyoan Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 6 November 2018.

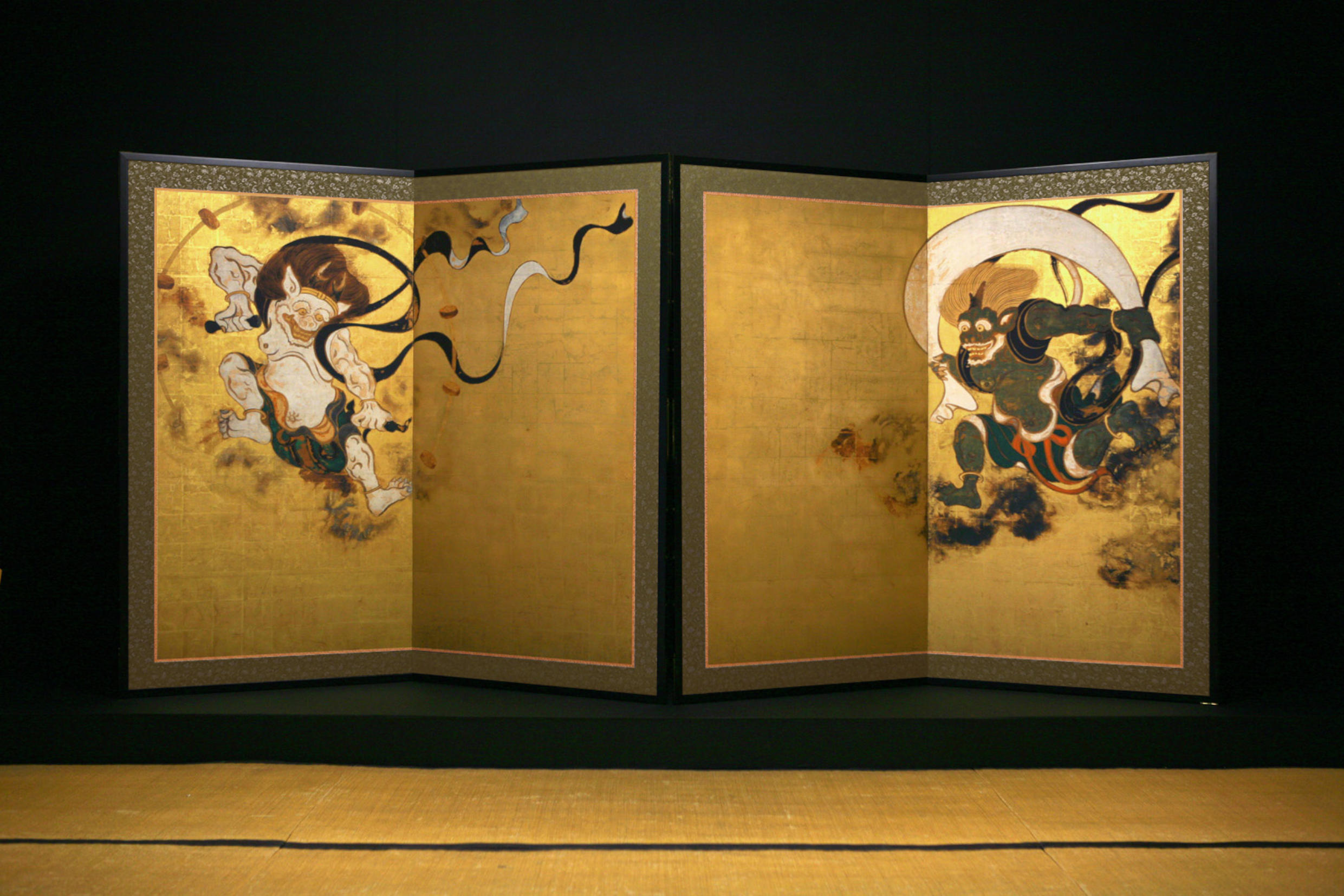

At Kenninji Temple, the present writer went to see the original “Wind and

Thunder Gods” painted by Soutatsu Tawaraya

The wind gad and thunder god painted by Soutatsu Tawaraya at Kenninji Temple.

Duplicated from: https://www.kenninji.jp/gallery/.

Another example of wild boar statue is found at Choushoin Sub-temple of Nanzenji

Temple in a northwest district of Kyoto.

Front view of Choushoin Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 10 October 2018.

Wild boar statues in front of the hall of Choushoin Temple. Photographed by M.

Iguchi, 10 October 2018.

Marishiten was adopted by the Nichiren Sect of Buddhism as a Gohouzenshin (護法善神,

heavenly gods who protect Buddha and Buddhists).[8]

The present writer has leant that a Marishiten statue which is said to be the

work of Prince Shotoku (聖徳太子) is held in Myosenzan-Tokudaiji Temple (妙宣山徳大寺), Ueno, Tokyo, and that a pair of wild boar statues stand in

front of the hall of Eishozan Honpouji Temple (叡昌山本法寺),

Nishijin, Kyoto, but has not visited those places.

Tiger statues

Tiger statues are seen in temples dedicated to Bishamonten (毘沙門天, Skt: Vaisravana), one of the Four Devas who protects the Buddhist world at four sides together with Jikokuten (持国天, Dhritarashtra), Koumokuten (廣目天, Virupaksa) and Zouchoten (増長天, Virudhaka). The fact that Bishamonten has a relation with tiger is only in Japan.

According to the legend of Shigisan Chogosonsiji Temple (信貴山眞言宗朝護孫子寺,

Shingon Sect)[9],

it was in 582 AD during the reign of Emperor Bitatsu (敏達天皇) “When Prince Shotoku

came to this temple in Yamato Province to beat Moriya Monobe, an Emperor's enemy

(anti-Buddhist), and prayed, Bishamonten appeared in the air and gave a secret

strategy. Incidentally it was the time of tiger, the day of tiger and the year

of tiger. After defeating the enemy (in the 2nd year of Emperor Youmei, 587 AD),

Prince Shotoku carved a statue of Bishamonten himself, built a temple and named

it Shin-gi-san, i.e., a holy mountain to be believed and respected.” Later,

Prince Shotoku founded the seven main temples, including the Houryuji Temple

(法隆寺), to establish the regime with Buddhism as the national religion. In the

early 9th century, the disease of Emperor Daigo was magically healed when Rev.

Myoren prayed. Thus, the temple was granted a holy name, Chogosonshiji Temple.

The image of Bishamonten which Prince Shotoku saw at Mt. Shigi (Shigisan) would

have been a Brockengespenst (Brocken spectre), although this interpretation may

spoil the sanctitude of the story.

In Singisan, tiger statues of various designs were found on the approach to the

Golden Hall of Chogosonsi Temple, four items as far as the present writer

witnessed, but they all were not the paired guardian tiger statues.

DSC_0620_smrt_40%25.jpg)

A view of Shigisan Chogosonshiji Temple from the Great Gate (Photographed by M. Iguchi, November 2021).

DSC_0617_smrt_40%25.jpg)

DSC_0592_40%25.jpg)

Left: A Big papier‐mâché tiger in the rear side of The Great Gate; Right: The

statue of a tigress with cubs that appeared next on the way to the Main Temple

(Photographed by M. Iguchi, November 2021).

DSC_0575_smrt_40%25.jpg)

DSC_0577_smrt_cut_cl80_35%25.jpg)

Left: A tiger statue in a cage just before the Seifukuin Temple (成福院); Right:

Statues of tiger family in a cage in front of the Seifukuin Temple (成福院) (both

photographed by M. Iguchi, November 2021). .

On the Tiger Day of 4th January in 770 AD, when

Gantei (鑑禎), a senior disciple of Rev. Ganjin (鑑真), climbed up to Mt. Kurama on

the back of a white horse, led by a dream, a witch appeared but he was safe by

praying to Vaisravana. A humble hut he built and dedicated to Vaisravana is said

to have been the origin of this temple.” In front of the temple’s Golden Hall

was a pair of guardian tiger sttues.

kuramasan_combined_2_cut_smrt_cut.jpg)

DSC_0686_cut_50%25_cut_cut.jpg)

DSC_0687_cut_50%25_cut_cut.jpg)

In addition to temples of Shingon Sect, tiger guardian statues are found also in Rinzai and Nichiren Sects temples as examples are shown below..

・Tamonin

Bishamondo Temple (多聞院毘沙門堂,

Shingon Sect), Tokorozawa

Front view of Tamonin Bishamondo Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 16 October

2018.

Located at 1501 Nakatomin, Tokorozawa, Saitama Prefecture, built by Lord

Yoshiyashu Yanagisawa of Kawagoe Clan. According to the temple’s legend,

Bishamonten statue of this temple had been carried by Shingen Takeda, a warlord,

in his helmet for war.

Tiger statues in front of the hall of Tamonin Bishamondo Temple. Photographed by

M. Iguchi, 16 October 2018.

Inscribed as: Dedicated by Kawagoeya Shinzo, Edo Gofukubashi-gai, September

1866.

・Ryousokuin Bishamondo Temple (毘沙門天堂, Rinzai Sect), Sub-temple of Kenninji Temple, Kyoto

Front of the hall of Ryousokuin Bishamondo Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 9

October 2018.

Tiger statues in front of the hall of Ryousokuin Bishamondo Temple. Photographed

by M. Iguchi, 9 October 2018.

Dedicated by Isuke Takeuchi of Matsubara Karasuma and Shu Sasaki of Gionkouji,

carved by Heishiro Tsuji.

・Tamonsan Tengenji Temple (多聞山天現寺, Rinzaishu-Tokudaiji Sect), Tokyo

Riving quarter (front) and the hall (back) of Tamonsan Tengenji Temple.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, 15 October 2018.

Left: Tiger statues in front of the hall of Tamonsan Tengenji Temple.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, 15 October 2018. The statues were carved by Toubei

Tachiuri of Kyobashi and dedicated by the group of believers of Tomisawa-cho.

Right: Tiger statues in front of the living quarter of Tamonsan Tengenji Temple.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, 15 Octber 2018. The statues were carved by Choubei

and dedicated by Sagamiya and Kuroki.

・Chingosan Senkokoji Temple (鎭護山善國寺, Nichiren Sect) at Kagurazaka, Tokyo

Front and tiger statues of Chingosan Senkokoji Temple. Photographed by M.

Iguchi, 13 October 2018.

The temple was originally founded at Bakurou-cho by Rev. Nissei, the 12th Chief

Priest of Ikegami-Honmonji Temple, requested by Ieyasu Tokugawa. After fires, it

was moved to Kouji-machi and finally at he present site in 1793. The statues

were carved and dedicated by Shirouyemon Hirata and Choyemon Yanagisawa.

・Shoruzan

Seidenji Temple (松流山正傳寺,

Nichiren Sect)

Front and tiger statues of Shoruzan Seidenji Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi,

15 Octber 2018.

Located at 1-12-2 Shiba, Minato, Tokyo. Originated from a hermitage of Emperor

Goyousei (1586-1611). The principal image, Bishamonten, is said to have been the

work of Rev. Dengyo (alias Saicho, 767-822). The tiger statues were dedicated in

1931.

All tiger statues shown above were dated. Among them, the figure of those which

were worked and/or dedicated before late Edo Period (the end of the 18th

century) did not look like real tigers. Live tiger were

imported into Japan already in Adzuchi Period in the 3rd year of Genki Era

(1572).[9a] In the Edo Period,

tigers were popular, as they were shown to public in show-booths and painted by

Jakuchu Ito (1716-1800),

Rosetsu Nagasawa (1754-1799),

et al., but the sculptors of such tiger statues as

above are supposed to have not seen them.

The present writer has learnt that fine tiger statues can be seen in Kuramasan

Kuramaji Temple in Kyoto and wish to visit theme sometime.

Mouse statues

Mouse statues placed at shrines which worship Ookuninushinomikoto (or

Lord Ookuninushi,

大國主命)

relate to a legend, written in Kojiki (古事記),

which is briefly as follows.

“Ashiharashikowo-no-mikoto (or Lord Ashiharashikowo,

葦原色許男命),

who later became Ookuninushi-no-mikoto, arrived at Nenokatasu Country (根堅州国)

where Susanowo-no-mikoto (or Lord Susanowo,

須佐之男命)

resided, and met Suseri-hime-no-mikoto (Lady-Princess Suseri,

須勢理毘賣命),

daughter of Susanowo. They immediately fell in love with each other and had an

intercourse. Susanowo who did not like to approve Ashiharashikowo to be his

daughter’s partner put him into various trials. Ashiharashikowo was given a

snake hut and a bee hive hut but he escaped danger by waving a scarf, which had

been given by the princess, as she told. He won a swimming race. Finally he

was invited to an archery competition and, in the grass field, surrounded by

fire which was intentionally set by Susanowo but, guided by a flock of mice,

fled for safe into a hole under the ground. After then, Susanowo gave an orders

to Ashiharashikowo and Suseri to get rid of lice from his hair but the couple

deceived him and, while he fell into asleep, rowed the boat far out to the sea.”[10]

Thus, mice became the divine messenger (or kindred) of Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto.

For reference, the above episode was written

in The aged Susanowo-no-Mikoto,[11]

a novel by Ryunosuke Akutagawa.

Daikokusha Shrine (大國社),

a sub-shrine of Ootoyo Shrine (大豊神社)

at the Higashiyama hillside in Kyoto is known as a shrine which worships

Ookuninushi-no-mikoto (大國主命).

The mouse statues of the present writer’s target found in front of the shrine

looked old significantly old ones but they were really not, the year of

dedication being inscribed as 1969. The round vessel and scroll held by the

left- and right-hand side statues are said to represent sake (the medicine for

perennial youth and long life) and the archive of knowledge, respectively,

according to an Internet article

The front and the mouse statues of Daikokusha Shrine, in the precinct of Ootoyo

Shrine, Kyoto. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 9 October 2018.

Built 5 May 1969, designed by the Priest Tsuneyoshi Kobayashi and donated by

believers to commemorate the renewal of roof.

Sugiyama Shrine at Tobe in Yokohama is another shrine in which

Ookuninushi-no-mikoto is enshrined. According to the shrine’s legend,[13]

the foundation dates back to 652 AD in Asuka Period when a part of the deity of

Izumotaisha Shrine (出雲大社)

was ceded: Although the shrine had been revered as the regional shrine, all

buildings and treasures were burnt away by the Great Kanto Earthquake (1923)

and, after an absence, the shrine was rebuilt in 1966. Both the left- and

right-hand side mouse statues found in front of the shrine held a magic mallet

in their right hands. Since the inscription on their basement was read as,

“1350th Year Anniversary” and “Members of Ceremonial Project Committee”, the

year of dedication is known as 2002. In front of the worship hall were a pair of

Chinse-type guardian statues. In the precinct, a sculpture of

Ookuninushi-no-mikoto, holding a magic mallet in his right-hand, carrying a big

bag on his left shoulder and sitting on three bales of rice, dedicated by Mr. Toshio

Kurosawa, an actor, was found. The present writer remember that he was told in his

childhood that the three bales of rice of Ookuninushi-no-mikoto (or Daikokuten)

represents the amount of rice for a person for one year, although the source is

unknown.

The front and the mouse states of Tobe Sugiyama Shrine, Yokohama. Photographed

by M. Iguchi, 2 February 2019.

Statues of Shishi-komainu lions and a Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto at Tobe Sugiyama

Shrine, Yokohama. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 2 February 2019.

Ookuninushi Shrine in Naniwa-ku, Osaka, is said to be famous as a shrine to

worship Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto.

Left: Ookuninushi Shrine. Middle and Right: Mouse statues. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 29 September 2019.

Mouse statues do exist also in

a Buddhist temple, Shojusan Fukusouji Temple (Nichiren Sect) in Horinouchi, Suginami, Tokyo,

which enshrines Daikokuten (大黑天). Why mice in a Buddhist

temple?

The reason is simple. A theory[14]

has it that, because the Chinese characters for

Ookuni (大國)

can be alternatively read as Daikoku,

Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto was syncretised to Daikokuten in the course of history.

Thus, mice which were the divine messengers of Ookuninushi-no-Mikoto would have

been automatically adopted to Daikokuten.

Daikokuten, who was derived from Mahakala, the Hindu

God of Darkness, or an incarnation of Siva, was introduced in the 7th century

into Tan Dynasty China by I-Tsing and transcribed as “大黑”.[15]

In Japan, it is said that Rev.

Saicho (最澄) had worshipped Mahakala for the first time in the 8th

century as written in the Legend of

Three-faced Daikokuten of Hieizan.[16]

The story is briefly as follows. “During the

construction of Konpon-Central Hall at Mt. Hiei (in the 7th year of

Enryaku, 788 ZD), a hermit appeared in front of him. Asked who he was, he

recited the phrases of Hokke Sutra (Lotus Sutra).

When Saicho begged supports for his disciple monks, the hermit said, “I shall

give you food for three thousand persons every day. I shall bestow happiness,

prosperity and longevity on those people who revere me.” Saicho who thought the

hermit must be the Three-faced Daikokuten purified himself, carved a

Three-face-six-arm Daikokuten statue, in the “one cut-three bows” manner, and

dedicated the statue in the hall.”

According to Historical Document of Tokyo

City,[17]

Shojusan Fukusouji Temple was founded by Nichiren Priest, Nichiju

(日重)

in 1589 at Shitaya and later moved to Keiseigakubo (Koishikawa-Hakusan-mae)

[Revised Edo Bulletin];

The founder’s statue is the work of Rev. Nisshin (日親) [Hokke sacred sites]; The gate is wood-made, the crest of Igeta

(shape of the character,

井)

is on the door, the hall faces north; in front of the hall are statues of mouse

(one pair) mounting on the bale of rice, behind the hall is a small pond

[New Illustrated Tokyo Sights]: etc. The temple was moved to the present site in

the 12th year of Showa (1937).

In the present Fukusouji Temple, the pair of mouse statues existed not right in

front of the hall but on the left-hand side of the entrance, presumably because

the hall is not in the right front of the gate. The sculpturing was detailed as

the body hair was lined on the stone surface but no whiskers were added. On the

sides of the basements were inscribed the list of donators, i.e., 16 from Osaka,

3 from Kyoto, 1 from Senshu-Sakai and 8 from Edo, “The coordinators: Izumiya

Kichiemon and Kugiya Jubei of Osaka”, “The petitioner: Imadzuya Heiemon of

Edobashi (Osaka)”, and the date, 3rd year of Kaei (1850), suggesting that this

temple was supported also by merchants of Osaka-Kyoto area.

Such statues of mouse mounting on the bales of rice, instead of Daikokuten, do

not seem to exist in other temples in Japan, as far as the present writer has

surveyed, and considered to be very important.

The gate (left) and the hall (right) of Shojusan Fukusouji

Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 13 February 2019.

Left: Front of the hall of Shojusan Fukusouji Temple. Mouse

statues, a flagpole and a rain-water receiver are seen. Right: Mouse statues and

a flagpole (close-up). Photographed by M. Iguchi, 13 February 2019.

Details of mouse statues in Shojusan Fukusouji Temple. Left statue (front, rear), Right statue (front, rear). Photographed by M. Iguchi, 13 February 2019.

Mangan-Daikikuten of Shoshusan Fukusouji Temple (not open for public).

Duplicated from: http://www.city.suginami.tokyo.jp/_res/projects/default_project/_page_/001/031/586/75.pdf

Fox statues

Fox statues can be seen in Inari Shrines, everywhere in Japan, the number of which being estimated as many as over thirty-thousand, but the principal deity of Inari Shrine is Inari-shin (稲荷神, lit. the god of rice) and foxes are assumed to have been made the deity messengers (or kindred) in the Heian Period, due to the fact that the shape and colour of fox’s tail resemble the ear of rice plant and also the fact that foxes catch mice which eat away rice.[19]

The head shrine of Inari Shrines is the Fushimi Inari Grand Shrine (伏見稲荷大社),

located in

Fukakusa, Fushimi, Kyoto, on the hill of Mt. Inari at the south end of

Higashiyama Thirty-six Peaks. According to the shrine’s legend, the Inari-shin

came to settle at Mt. Inari in 711 AD. Although it was a weekday morning when I

visited there, anywhere from the approach to the precinct was full of people and

reminded me of the climax scene of the novel by Ougai Mori,

The vengeance at Gojiingahara,[20]

in which Bunkichi visited Tamatsukuri-Fukuu Inari Shrine to enquire an oracle.

In fact, the present writer needed to be patient to wait for the momentary

dispersion of people to press my camera shutter.

Left: Ootorii (The grand gate) of Fushimi Inari Grand Shrine, Kyoto. Right: A

part of the Senbon Torii (One thousand Gate) of Fushimi Inari, viewed from the

upper side. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 10 October 2018.

Pairs of fox statues at The grand gate (left) and at the starting point to

Mt. Inari by the Worshipping Hall (right). Photographed by M. Iguchi, 10 October

2018.

The four foxes in the above pictures, from the left to the right, hold in their mouth a scroll, an orb, an ear of rice plant and a key, in their mouth, which symbolise the knowledge, the spirit of the god, the good harvest and the key of granary, respectively.[21]

The Otome Inari Shrine (乙女稲荷神社), a sub-shrine of Nedzu Shrine (enshrined deity:

Susanowo-no-Mikoto), Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo is another place the present writer has

visited. The two statue foxes in this shrine showed open and closed mouths, the

typical mouth-forms of Shishi-komainu guardian lion statues.

The approach to the Nedzu Shrine, Tokyo. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 13 October

2018.

The front and the fox statues of Otome-Inari Shrine, in the precinct of Nedzu

Shrine, Tokyo. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 13 October 2018.

Ox statues

Kitano Shrine, located at Koishikawa in Tokyo (1-chome, Bunkyo-ku), is related to an ox, as it is known as Ushi-Tenjin (lit. Ox-Heavenly deity), and in the precinct is a pair of ox statues which guards the main hall. According to the guide board in the precincts, the history is essentially as follows.

“In the spring of 1184, the 3rd Year of Juei Era, when General Lord Yoritomo of Genji was waiting for the calm of the sea on the estuary near-by during his campaign to the north-east Japan, Godly Michizane Sugawara on the back of a divine ox appeared in his dream and told him he would have two fortunes. When he awoke, beside him was a rock which resembled the ox. In fact a son, Yori-ie was born in autumn and the archenemy Heike was defeated next year to restore peace. Then, Lord Yoritomo built this Tenjin Shrine for Godly Sugawara and contributed a land, the 1st Year of Genryaku Era.”

Certainly the shrine deifies Michizane Sugawara, as written in the guide board. The phrase, “the estuary near-by”, may be questionable for some readers. Although this place is now far away from the sea, the coastline of before land reclamations and river works were implemented after the Edo Period was complicated.

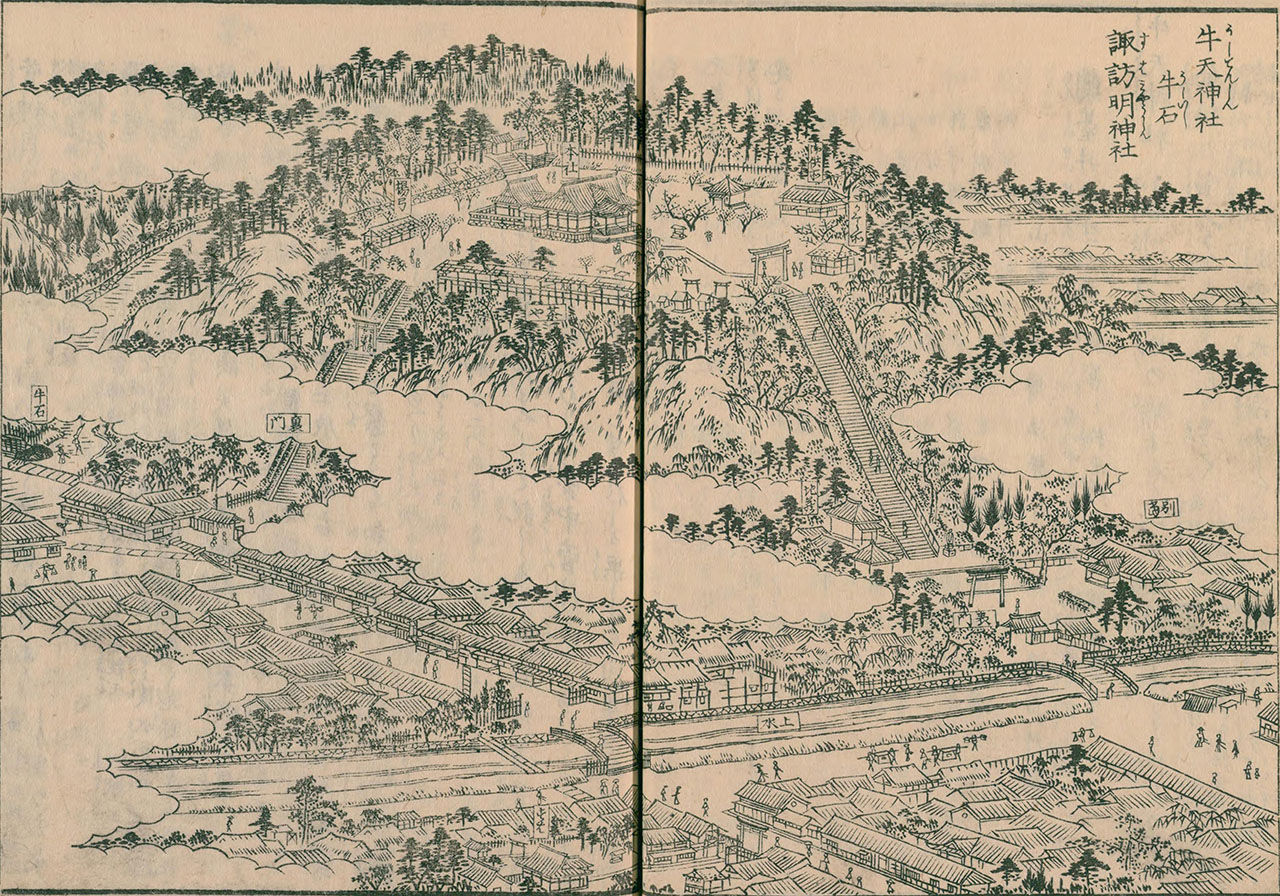

Edo Bay in the Doukan Period. Motoki Kuroda, "Illustrated Doukan", Ebisukosho Publishing 2009 (Redrawn by the present writer.)

Doukan Oota (1432 - 1486) was a powerful vassal of the Uesugi Family in the Muromachi Period (1336 - 1576). He built Edo Castle in 1457.

According to “The History of Koishikawa Ward (1935)”[1], this area was a busy town as described in “Illustrated Famous Places in Edo” and nightlife spot as included in Kunisada Utagawa’s “One hundred Beauties in Edo (1857).

Illustration of Ushi-Tenjin Shrine, in: Nagaaki Saito (ed.), Settan Hasegawa (illust.) “Illustrated Famous Places in Edo” Vol. 4, Part 4/4, Suharaya Ihachizou Press 1834-1836. Duplicated from: https://jinjamemo.com/archives/ushitenjinkitanojinja.html

Left: Kunisada Utagawa: “One hundred Beauties in Edo: Koishikawa Ushi-Tenjin (1857). Held by Tokyo Metropolitan Library. Duplicated from: https://ja.ukiyo-e.org/image/metro/025-C001-035. Right: Cut of the same, enlarged.

The approach seen in the right-hand side in the “Illustrated Famous Places in Edo” had been demolished and now we ascend the stone steps above “Rear Gate” found on the left-had side. Cleaning hands at the hand-wash basin found by the left-had side in the front and entering the gate guarded by shishi-komainu statues, we meet a pair of ox-statues. In the left corner lies the ox-shaped rock which Yoritomo saw in his dream. Since the stone was drawn in the Illustrated Famous Places in Edo” on the left side of the “Rear Gate”, it must have been hoisted above the hill in a later time.

Kitano Shrine – Ushi-Tenjin, front view of the main hall. Photographed by the present writer, 2020.07.27.

Kitano Shrine – Ushi-Tenjin, the pair of ox statues in front of the main hall. Photographed by the present writer, 2020.07.27.

Kitano Shrine – Ushi-Tenjin, the ox-shaped rock which is said to have been seen by Yoritomo in his dream. 2 Photographed by the present writer, 2020.07.27.

In the middle of the precincts was a large sacred tree of Mokkoku (Cleyera) and on the edge of the southern cliff was a Poem monument of Utako Nakajima, a famous female poet in the early Meiji Period who opened a private school, “Haginoya”, to teach poem and calligraphy. For reference, Ichiyo Higuchi was her pupil.

Left: The sacred tree of Mokkoku (Cleyera) in Kitano Shrine – Ushi-Tenjin. Right: The Poem monument of Utako Nakajima, a female poet in the early Meiji Period. Both photographed by the present writer, 2020.07.27.

In the precinct were two sub-shrines, Oota Shrine and Takagi Shrine, which enshrines the god of the performing arts and the god of five grains but they are not described about in this article.

[1] Takawosan Jingoji Temple Homepage: http://www.jingoji.or.jp/

[2] 神まうで (Kami-maude=Visiting Shrines), Ministry of Railways 1933, p.89-90.

[3]

Yoshyuki Ogino,

註釈日本歴史

(Interpretation of Japan’s history), Tokyo Hakubunkan, 1919; Nobuo Kuroita, Tei

Morita,

日本後紀

(Nihon

Kouki), Shueisha, 2003; Mutsuo Hayashi,

完訳注釈続日本紀:第5巻 (Perfect

translation: Shoku-Nihonki: Vol.5), Gendai-shisosha, 1988; etc.

[4] Hikoichi Naito (ed.), 和氣清麻呂忠義傳 (Legends of loyal Wake-no-Kiyomaro), Naito Hiroichi Publ., 1887.

[5]

Shoichi Watanebe,

日本史百人一首 (Nihonshi

Hyakunin-isshu), Fusousha 2008

[6]

Kengyo Tsukamoto (ed.),

国訳密教:

経軌.

第1 (Translation of Esoteric Buddhist Sutras No.1), Kokuyaku Mikkyo Kankoukai

1920-23

[7] Zenkyoan Homepage: http://zenkyoan.jp/about_marishiten/

[8] Marishiten Tokudaiji Homepage: http://www5b.biglobe.ne.jp/~marisitn/marisiten.htm

[9] According to the homepage of Shinkisan Chougosonshi (http://www.sigisan.or.jp/), the year was 582 AD during the reign of Emperr Bitatshu.

[9a] In the column of the 3rd year of Genki Era (1572) in Chikuun Uchihashi (Ed.), Nagasaki Nenreki Roumen Kan (lit. Double-sided mirror of Nagasaki chronicle) 1828, it was recorded, "A Chinese ship arrived at the port of Usuki, Bungo District. The ship brought 4 tigers, 1 big elephant, peacocks, owls, musk and various other items."

[10] Yoshinori Yamaguchi, Takamitsu Jinnoji(trans), 新編日本古典文学全集 (1) 古事記 (New Ed. Japan Classic Literature (1)Kojiki), Shogakkan 1997.

[11]

Ryunosuke Akutagwa,

老ひたる素戔嗚尊

(Aged

Susanowo-no-Mikoto), published in 1920.

[12] http://www9.plala.or.jp/sinsi/07sinsi/fukuda/nezumi/nezumi-2.html

[13]

Sugiyama Shrine Brochure.

[14]

Noboru Miyata (ed.),

神仏信仰事典シリーズ: 七福神信仰事典

(Encyclopaedia

of Gods and Buddha), Ebisukousho Publ., 1998.

[15]

Sadahiko Tanido,

七福神と聖天さん―民間信仰の歴史 (Shichifukujin

and Seiten), Taigen Publ., 2005.

[16] Hieizan

Enryakuji Homepage:

https://www.hieizan.or.jp/wp-content/themes/enryakuji/pdf/daikoku_engi.pdf

[17]

Tokyo City Office (ed.),

東京市史稿:宗教篇第三

(Tokyo City History Archive), 1940.

[18] http://www.city.suginami.tokyo.jp/kyouiku/bunkazai/sitei/1032395.html

[19]

Yo Nakamura,

イチから知りたい日本の神さま[2]稲荷大神 (Shichifukujin),

Ebisukousho Publ., 2009.

[20]

Ougai Mori,

護持院原の敵討

(Gojiingahara

no katakiuchi). First published 1913.

[21]

//////