3. Dvarapalas or Deva King Statues

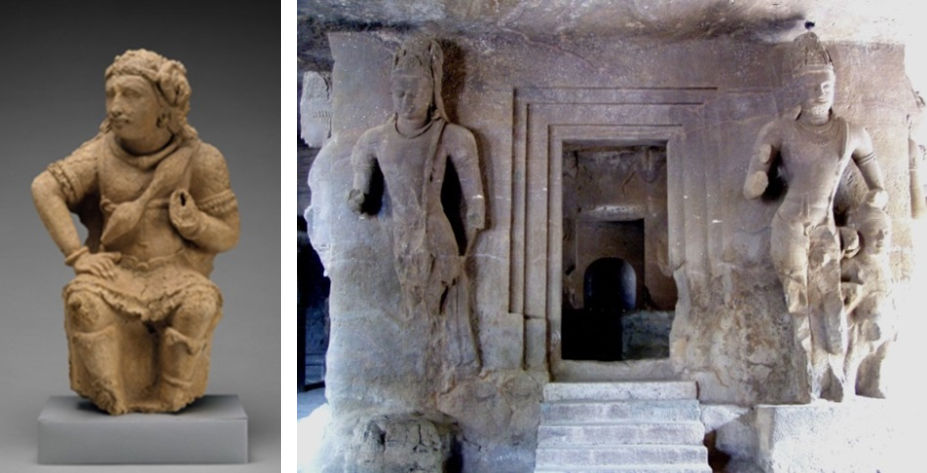

In Chapter 5 of my Java Essay[1], “Mataram where Gods and Buddha Reside”, I wrote about the common view that “the origin of Deva King Statues dated back to Gandhara” but archaeological finds named Dvarapala (or Dwarapala) were rather rare. One example found in the Internet was a sitting statue held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, named “Door Guardian (Dvarapala), ca. 4th century, Gandhara” which looked dissimilar to the muscular Hercules of Greek sculptures, having a bow instead of a truncheon, a Deva King’s common weapon. Another example is a picture, entitled “One of the many lingam shrines in Elephanta caves complex”, at the site in Elephanta Island, off Mumbai [5-8th century], in which the body form was also different from that of Greek Hercules.

Nevertheless these facts would not necessarily deny the conjecture that Deva King Statues designed after Hercules would have existed in Gandhara. Fragments of Gandharan relief in which the Greek divine hero Hercules was assumed as Vajradhara (a protector of Buddha) are seen in the British Museum and elsewhere and statues Hercules with the gate guarding were found in Ephesus, a Hellenic city in the west end of Asia Minor, the present-day Turkey.

Left: Door Guardian (Dvarapala), 4th century, Culture: Pakistan (ancient region of Gandhara), Stucco. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/38498.

Right: One of the many lingam shrines in Elephanta caves complex

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elephant_Lingam_shrine_1.JPG. [5-8th c. A linga, symbol of Shiva is seen in the hall.]

Left: Heracles depiction of Vajrapani as the protector of the Buddha, 2nd century Gandhara. British Museum.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greco-Buddhist_art#mediaviewer/File:Buddha-Vajrapani-Herakles.JPG.

Gandhara,

Right: Hercules and the nemean lion, 1st century. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Met,_gandhara,_hercules_and_the_nemean_lion,_1st_century.JPG.

To my knowledge, the oldest exiting dvarapala statues in Java are a pair of pieces in the front of the gate of Candi Sewu which was constructed in 780s AD during the era of the 4th King Indra of Sailendra Kingdom in Prambanan Plain. No dvarapala are found, whether they were absent from the beginning or extinct in later times, not only in the Candi Kalasan built in 778 AD in the era of Indra’s father, the 3rd King Wisnu, but also in three candis in Kedu Basin, i.e., Candi Mendut, finished in 782 AD by King Indra, Candi Borobudur completed in 824 AD by his son, the 5th King Samaratungga, and the Candi Pawon erected in 820th by his granddaughter, Pramodawarhani.

In any case, one may suppose that the convention to place dvarapala statues in front of the temples in India was introduced some time in Java, for instance, by a visitor or invitee to Borobudur or some other temples.

Dvarapala statues at the front gate of Candi Sewu, built in 782 AD (704 Saka) Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2007.

Dvarapala statues of Candi Plaosan. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2006.

The dvarapala statues in Candi Sewu are fat Rakshasa statues similar to those in Candi Plaosan (included in Java Essay) and that they represented Vajrapani is almost certain from their weapons, a truncheon to beat intruders and a rope or naga (snail) to tie them up, both the common possessions of the deity, although the dvarapala’s body form is different from those of muscular wrestlers in Horyuji Temple and Todaiji Temple in Japan.

As written above, no Dvarapala statues exist in Kedu Basin to my knowledge but recently (June 2019), when I visited the National Museum of Indonesia, Jakarta, I found in the collection a pair of Dvarapala labelled as "Dvarapala, The guard of temple gate, Origin: Kedu, Central Java, Century: 8th - 9th, No. Inv. 210", collected sometime in the past, presumably in the early 19th century when archaeological survey started. The curving remains sharper probably because, having been placed under the roof, they did not suffer the erosion by acidic rain that is nowadays a serious issue.

A pair of Dvarapala statues "from Kedu in the 8th - 9th Century" in the collection of National Museum of Indonesia, Jakarta. Photographed with permission by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (New).

Let us briefly review the history of Buddhism in Java that was described in some detail in my book, Java Essay.

It was from the early 8th to the mid 9th century during the era of the Sailendra Kingdom that Buddhism, viz., Mahayana Buddhism, most prospered in Central Java. Sanjaya Kingdom, or Mataram Kingdom, founded by Sanjaya Harisdharuma who moved from West Java, coexisted with the Sailendra Kingdom. The former worshipped Hinduism but supposedly admitted Buddhism to some extent, as the Buddhist Candi Kalasan is said to have been constructed by Panangkarang, Sanjaya’s son, who married Princess Tarapramatama of the Sailendras. Rakai Pikatan who was to become the next king of Sanjaya married to Princess Pramodawardhani, daughter of King Samaratungga of the Sailendra Kingdom, in the heyday of the latter kingdom. I would imagine that Pramodawardhani had an excellent talent and strong faith to Buddha inheriting from her father. Historians consider that the two kingdoms were essentially unified by their marriage. The younger brother of Pramodawardhani, Balaputradewa who wished the continuation of Sailendra Kingdom in Java challenged his elder brother-in-low, Rakai Pikatan, but eventually moved, whether defeated or reconciled[2], to Sriwijaya, his mother’s home country and had the title of the King of Sailendra.

A country recorded in the Old Book or Tang, as 訶陵國 (pronounced as Kalinga or Ho-ling country in the West) is no doubt the Keling Kingdom written in old West Java manuscripts, Pustaka rajya rajya i bhumi Nusantara and Carita Parahiyangan, according my consideration (See, the separate section, I-2 of this web page). The country developed by Kartikeyasingha (648-674) worshipped Saura (a fact of Hinduism) at least during the era of Queen Sima (悉莫 in Chinese) who inherited the kingdom from her husband. Although she rejected the marriage proposal of Jayanasa, the king of Buddhist Sriwijaya Kingdom in Sumatra, and the latter gave up the wish to take her and her country as the surrounding countries took side with Sima, but the Keling became under the influence of Sriwijaya in later years and Buddhism was practiced to some extent when Sanjaya unified Java in early 8th century..

In the early 13th century in East Java, Ken Arok, a prominent hero from sudra, the lowest Hindu caste, founded the Singasari Kingdom by assassinating Tunggal Ametung, a tyrannical regional governor under the control of Kediri Kingdom, and married to Ken Dedes, the daughter of a Buddhist priest, Mpu Purva, whom Tunggal Ametung had kidnapped and made his wife. According to a phrase in Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s novel[3], Arok aimed at a society in which believers of different religions were harmonised. Then, Buddhism was also accepted, and in front of Candi Singosari complex, the main candi of which has remained to date, were placed a pair of very large dvarapala statues.

Huge dvarapala statues at Candi Singosari, built in 1268 AD (1190 Saka). Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2010.

The national ideology of Indonesia, “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” (Unity in Diversity) is generally said to have originated from a clause, “Buddha and Siwa are one in their deepest essence” found in the tale of Sutasoma written in the Majapahit period, but one may consider that the syncretisation of Hinduism and Buddhism had commenced in Ken Arok’s time, or earlier with the marriage of Rakai Pikatan and Pramodawardhani of Sanjaya and Sailendra Kingdoms.

Why Buddhists such as the father of Ken Dedes, Mpu Purva, existed in East Java far away from Mataram casts a question. I would imagine that those Buddhists of the Sailendra kingdom or those from the Keling kingdom under the control of Sriwijaya had migrated and lived there for many generations. In the suburb of the present-day Malang remains a Buddhist stupa, Candi Sumbrawan, which is assumed to have been erected in the 14-15th century in the Majapahit period.

In the Majapahit period the syncretisation of Hinduism, Buddhism and Tantrism was matured. In Panataran Temple Complex located to the north of the present-day Blitar, Buddhist and Tantric sculptures as well as Hindu ones were adorned on the walls of buildings and a set of fine dvarapala statues were placed at the main gate and more sets, in the interior of the vast precincts.

Dvarapala statues at the front gate of Candi Panataran. Photographed by M. Iguchi, May 2009.

A view of the Candi Panataran Complex. The tower seen in the middle is the Dated Temple, and the front gate is located behind it in the distance. The building in the right-hand side is the Naga Temple. Several pairs of dvarapala statues are seen spot-like along the approach. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

In front of the remaining three-storeyed basement of the main temple, there was a pair of statues which were dissimilar to fat Rakshasas dvarapala. They were better-proportioned, hanging down hair and being accompanied by a short figure that looked like a female. The only one description about these statues I have so far found is in a legend of photograph in the Internet[4], “This is one of four tantric dvarapalas that guard the staircases of the main temple. Each guardian stands on a skull platform, holding a club in one hand and carrying a snake over his shoulder. The smaller figure on the other side of the guardian is his consort.”

Dvarapala statues in front of the main temple of Candi Panataran. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

In front of the Dated Temple (Candi Angka Tahun), located in the central area of the precinct, was another pair of slender divine statues which, at a close look, appeared to be a male and a female deities with four arms, although their faces were not clear for erosion. Although no literature was found, the male statue might represent Vaisravana, one of the Buddha’s guardian, and the female one, Srimahadevi, his consort or sister. These statues having no weapon and pressing their palms may not be classified in the category of dvarapala that protect Buddha with physical strength.

Statues of male and female deities in front of Dated Temple in Candi Panataran Complex.

Top: Full portraits. Photographed by M. Iguchi, May 2009.

Bottom: Busts. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

From the collection of Penataran Museum (mentioned in the First Section), I present several photographs of dvarapala statues. The features of all statues were quite different from the traditional ones which represented fat Rakshasa. The dvarapala in the front garden held a unique truncheon with parallel stripes and his cap had corners. This statue looks more or less similar to the pieces held in Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, labelled as “Door guardian ( one of a pair), approx. 1300-1400, Andesite, East Java, Majapahit.”

In any case, dvarapala statues of individualistic design are considered to have been produced according to the image of artists, regardless to the traditional model.

A phrase in the legend to the statues of San Francisco Asian Art Museum, “These figures would have flanked the entranceway of a Hindu temple in the kingdom of Majapahit (approx. 1300-1500) centred in East Java” is probably not precise and “a Hindu temple” ought to be read as “a Hindu temple with Buddhist elements”. No dvarapala was seen in pure Hindu candis in Java which I looked around, because, if I am not mistaken, Vajradhara embodied in dvarapala was a deity of Buddhism origin, while many deities of Buddhism were inherited from Hinduism.

Dvarapala statues in Penataran Museum. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Left: A dvarapala statue in the front garden of Penataran Museum. This is the original piece as seen from the serial number, although the history is unknown. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Right: A pair of dvarapala statues in Asian Art Museum, San Francisco. http://searchcollection.asianart.org/view/objects/asitem/id/26073.

In Candi Sukuh constructed on the west slope of Mt. Lawu in 1437 in the declining period of Majapahit Kingdom under the pressure of Islam, as a temple guardian, there was a dvarapala statue among various sculptures placed in the precinct, in addition to a Kala’s head hung at the lintel of the front gate. The type of dvarapala was dissimilar to the traditional ones designed after fat Raksasa statues, as seen in Panataran and elsewhere, having an enormous head that was as large as its body and showing a large mouth with upper and lower teeth. The details were unclear due to the erosion but, judging from the vajra held in the right hand, I thought the statue meant the Vajradhara.

Left: A view of the precinct of Candi Sukuh. Right: A dvarapala statue.

Both photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006.

At another slope of Mt. Lawu about 500 metres above Candi Sukuh is Candi Cetho built in 1450-70 in the last days of Majapahit. This candi was not a masonry structure. The main temple located above a long approach with staircases was made of wood and ashrams and monk’s quarters on both sides of the approach were also wooden constructions. Along the approach there were a number of human figures that were sitting and apparently mediating or praying to the gods but, without vajra and lope, they were definitively not dvalaparas who protect a temple with muscular powers.

A local gentleman told me that in the region were Hindu inhabitants who were the descendants of people who escaped from Islam many centuries ago. Since flowers and incenses were offered to holy statues, I thought this candi was not an abandoned temple, although it had no splendour of the old days. Below the ascending approach was a stone made split gate which was similar to those popular in Bali, constructed in a recent decade. A figure found in front of it did not look like a dvarapala either.

Left: A flat plot in the approach of Candi Cetho where a huge step-stone designed after a tortoise and several human figures are seen.

Right: An example of human figures.

Both photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006.

A split gate below the approach of Candi Cetho (left) and the magnified view of the human figure (right).

Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006.

A piece of photograph of dvarapala statues at Pura Puseh, Bali, taken some years ago has been found in an album. The year of this temple’s foundation, 944 Saka (1022 AD) was in the era of Warmadewa Kingdom, when Prince Airlangga from the Balinese royal family arose in Java to rebuild a kingdom in Java. The model of the dvarapala was not Rakshasa adopted in Java but demon queen Rangda, an eternal archenemy of Barong, a benevolent beast in Balinese Mythology, and this model seemed to be common in Bali. These statues are supposed to be a work in a later year but the detail is unknown to me.

Dvarapala statues at Pura Puseh Temple, Batuan Village, Bali. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2005.

With the founding of the New Mataram Kingdom in the 16th century, Old Javanese Culture that flourished before the Islamisation was revaluated and the statue of Dvarapala revived. Dvarapala statues placed at the entrance of Hadiningrat Palace of Surakarta (Solo), constructed in the late 19th - early 20th Century, and the Donopratopo Gate of Yogyakarta’s new palace, constructed in the early 20th Century, were of classic-type which depicted fat Raksasa. The statues at Yogyakarta looked to be made of metal.

Front view of Hadiningrat Palace, Solo. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (New).

Dvarapala statues at the entrance of Hadiningrat Palace, Solo. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (New).

The front view of the Donopratopo Gate of Yogyakarta Palace. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (New).

Dvarapala statues at the Donopratopo Gate of Yogyakarta Palace. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (Replaced).

Dvarapala statues are found in front of public buildings and old hotels elsewhere in Indonesia. The dvarapala at the entrance of Hotel Inna Garuda, Yogyakarta, wore fine moustaches and those in Hotel Tugu, Blitar, had sharp animal ears and fangs in their mouth. Thus, the design of dvarapala made for ornaments is diverse.

Dvarapala statues at Hotel Inna Garuda, an old Hotel in Yogyakarta. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Dvarapala statues at Hotel Tegu, in Blitar. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

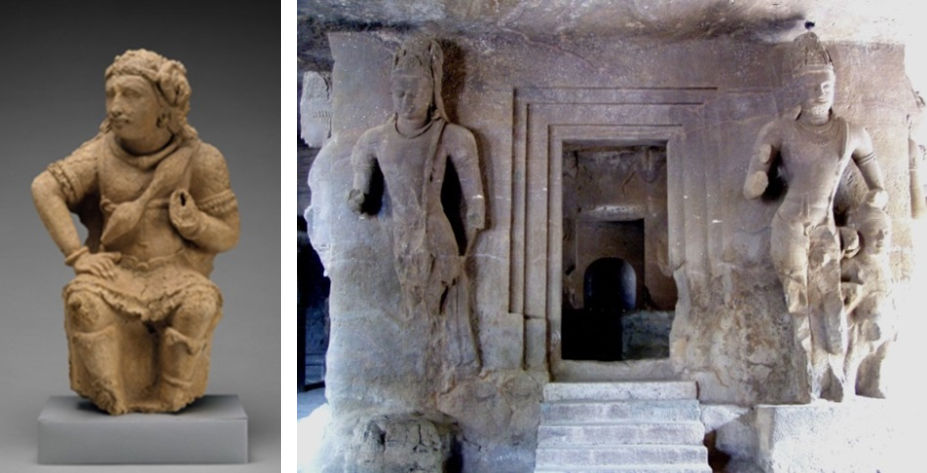

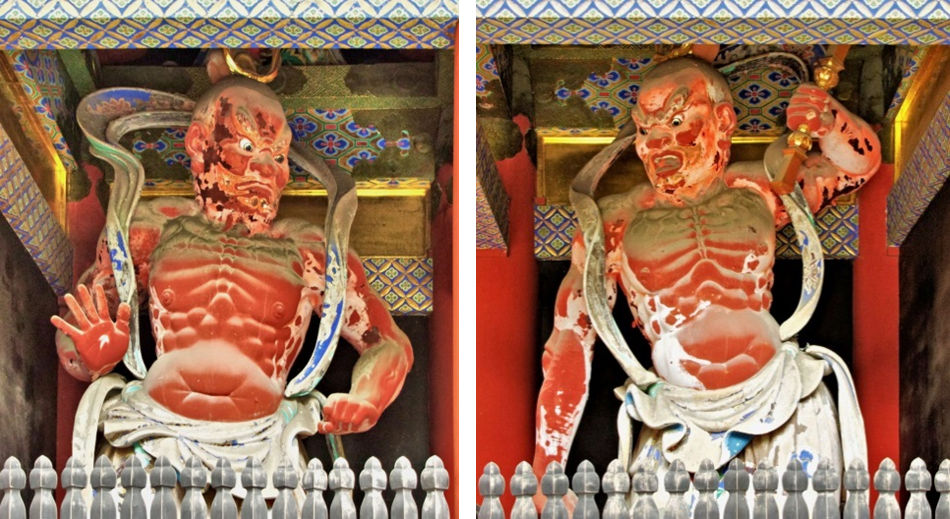

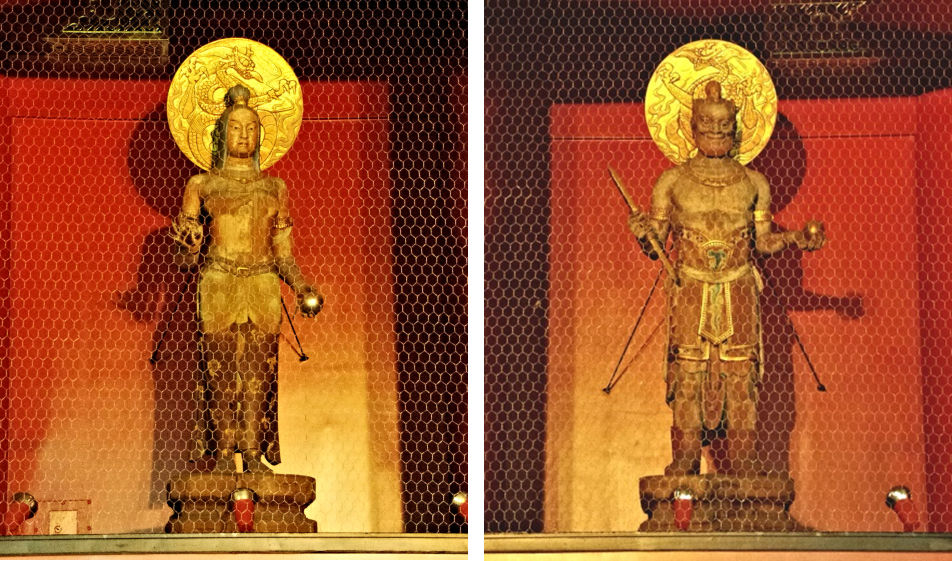

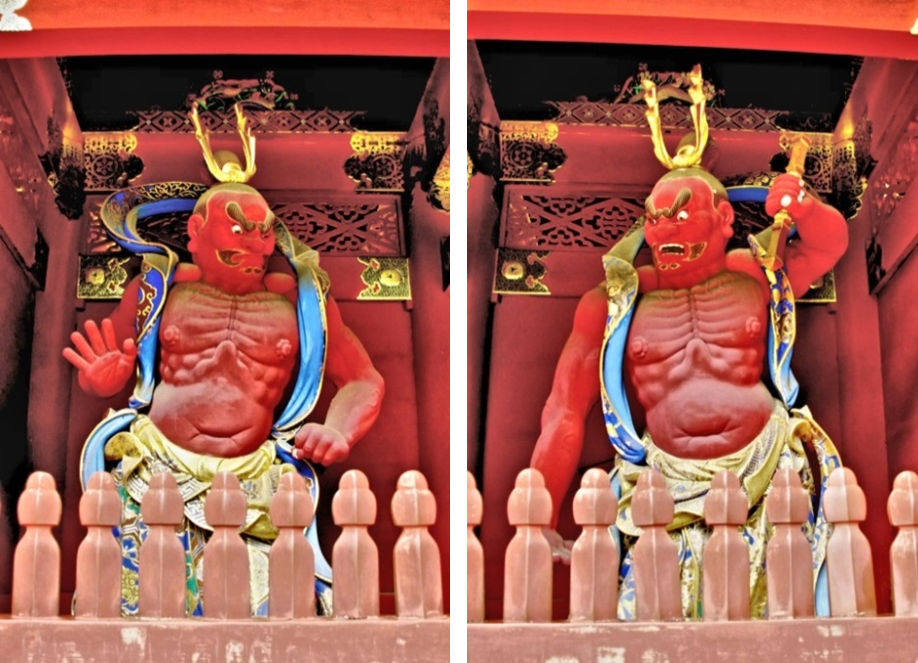

(5) Niou statues, or Deva-King statues, in Japan

Let me show photographs of Niou statues in Japan depicting muscular wrestlers.

Niou statues at Horyuji Temple (worked in 711 AD, Clay), Nara, Japan. Photographed by M. Iguchi, November 2014.

Niou statues at The South Gate of Todaiji Temple (worked in 1203 AD, wood), Nara, Japan. Photographed by M. Iguchi, October 2014.

Left: Closed-mouth, by Joukaku, Tankei and 12 assistants.

Right: Open-mouth, by the master sculptor, Unkei, with Kaikei and 13 assistants.

Niou statues at Sugimoto Temple in Kamakura.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2014.

The statues are believed to be a work of Unkei. [5]

Niou statues at the main gate of Kashiwawozan-Daizenji Temple, Katsunuma, Yamanashi Prefecture. Photographed by M. Iguchi, October 2015.

Niou statues at Yomei-mon (gate), Toshogu, Nikko. A work of Hougen Kouon in 1638 AD. Photographed by M. Iguchi, August 2014.

Niou statues at the Niou Gate of Higashi-Kouyasan Iouji Temple, Kanuma, Tochigi Prefecture. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2016.

Wood, old colour, 13th c. Kamakura Period. Judging from the style, the statues are supposed to be the work of Keiha (Unkei’s school) [6]. The gate itself was rebuilt in 1992.

Niou Statues at Houzo-mon (Houzo Gate), Sousenji-Temple, Tokyo, sculptured by Kyusaku Muraoka in 1964.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2015.

In Sousenji Temple in Tokyo, there stands a front gate, commonly called Kaminari-mon (lit. Thunder Gate), at the entrance to the approach. As the proper name, Fu-jin Rai-jin Mon, means the Gate of Wind God and Thunder God, statues of the two deities are found in the left- and right-hand sides, respectively. Wind God and Thunder God are known in Hindu mythology as Vayu and Indra. An episode that Indra tried to shoot Garuda down with his thunderbolt in vain is found in the Garuda Myth included in [IV. Legends and Tales]. Whilst the linkage of these gods to Buddhism is said to have occurred earlier in Kushan, a pair of sculptures in Sanjusangendo Hall (lit. Hall with thirty-three spaces (between 34 pillars) and a picture on folding screen by Sotatsu Tawaraya, both in Kyoto, are well known in Japan, besides the dvarapalas in Sousenji Temple.

At the rear side of the gate there are male and female statues of Dragon Gods (Heaven Dragon God and Gold Dragon God) who preside over water, hence fight against fire. Besides these gatekeepers, statues of Virudhaka (増長天) and Dhritarashtra (持国天) are housed in Nitenmon (lit. Two deities gate) located to the east of Sensoji Temple.

Guardian statues of Fu-rai-shin-mon (Lit. Gate of Wind God and Thunder God), commonly called Kaminari-mon (lit. Thunder Gate), Sousenji-Temple, Tokyo.

Top-left (Front-left = Southwest): Thunder God .

Top-right (Front-right = Southeast): Wind God .

Bottom-left (Rear-left = Northeast): Gold Dragon God.

Bottom-right (Rear-right = Northwest): Heaven Dragon God.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2015.

The Wind God and Thunder God statues was originally sculptured in the late 17th century in Yedo-Period[7] [6] but both statues were burnt in 1864, leaving the head parts. The body parts were resculptured in 1874. They were repaired and repainted in 1960.

The statues of the Gold Dragon and Heaven Dragon statues were sculptured by Denchu Hioragushi adnYasuo Sugawara, respectively, and donated in 1978.

Virudhaka (増長天) and Dhritarashtra (持国天) in Nitenmon (lit. Two deities gate) of Sensoji Temple. Works of ca. 1649. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2016.

Statues of Wind God and Thunder God were found also in the rear side of Chuzenji Temple in Nikko that housed a pair of Niou in the front side.

Daiyu-in Temple that enshrines Iemitsu, the 3rd Shogun of Tokugawa, in Rinnouji Temple in Nikko had three gates, Niou-mon, Niten-mon and Yasha-mon. The statues of Jikokuten (Skt. Dhrtarastra) and Koumokuten (Skt. Virupaksha) in Niten-mon were absent when I visited there recently as the gate was under repair. In Yasha-mon were four Yaksha deities, Hidara, Umarokya, Abatsumara and Kendara.

Thus, in modern time Japan statues of various deities emerged as gate guardians of temple.

Statues of Wind God and Thunder God were found also in the rear side of Chuzenji Temple in Nikko that housed a pair of Niou in the front side.

Statues of Guardians in the main front gate of Chuzenji Temple, Nikko,

Top: A pair of Deva Kings at the front side.

Bottom: Fu-jin (Wind God), left) and Rai-jin (Thunder God, right) at the rear side.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, July 2015.

The buildings of the temple were rebuilt after destructed by a large landslip in 1902.

A pair of statues of Nious (Deva Kings) at the Niou-mon of Daiyu-in of Rinnouji Temple (constructed in 1653), Nikko,

Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2015.

Statues of Jikokuten (Skt Dhritarashtra, left) and Komokuten Virupaksha (Skt. Virupaksha, right) at the Niten-mon of Daiyu-in of Rinnouji Temple (constructed in 1653), Nikko. Since the gate is under renovation, pictures in the following website have been duplicated.

http://blogs.yahoo.co.jp/kassy1946/51585011.html

Daiyu-in Temple that enshrines Iemitsu, the 3rd Shogun of Tokugawa, in Rinnouji Temple in Nikko had three gates, Niou-mon, Niten-mon and Yasha-mon. The statues of Jikokuten (Skt. Dhrtarastra) and Koumokuten (Skt. Virupaksha) in Niten-mon were absent when I visited there recently as the gate was under repair. In Yasha-mon were four Yaksha deities, Hidara, Umarokya, Abatsumara and Kendara.

Bidara, Front-left (North).` Abatsumara,Front_right (East).

Umarokya, Rear-Left (West). Kendara, Rear-right (South).

Four Yaksha statues at the Yakusha-mon of Daiyu-in of Rinnouji Temple, Nikko, Photographed by M. Iguchi, July 2015.

Thus, in modern time Japan statues of various deities emerged as gate guardians of temple.

[1] 井口 正俊「ジャワ探究―南の国の歴史と文化」, 丸善プラネット 2013; Masatoshi Iguchi, Java Essay: The History and Culture of a Southern Country, Troubador Publishing 2014.

[2] According to Naskah Pangeran Wangsakerta, Balataputridewa was expelled by Kayuwangi, the son of his sister, Pramodawardhani, and her husband, Rakai Pikatan. Edi S. Ekadjati (Edit), Polemik Naskah Pangeran Wangsakerta, Pustaka Jaya 2005.

[3] Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Arok Dedes, Hasta Mitra, 1999/Trans. by Max Lane, Arok of Java, Horizon Books 2007. (A story of Ken Arok and Ken Dedes.)

[4] http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Candi_Panataran_Guardian _Java_1303.jpg

[5] 「美術手帖 第869号: 全国社寺・仏像ガイド」, 美術出版社 2005 (Art Handbook No. 869: A New Guide to Statues in Shrines and Temples in All Japan, Bijutsu-Shuppansha, Tokyo 2015).

[6] Private letter from the Cultural Assets Department, Kanuma City. June 2016.

[7] “Minbu [a sculptor] said that the Wind God and Thunder God in the Fu-rai-shin-mon of Asakusa were the works of his father” in: 網野宥俊,『浅草寺史談抄』, 金龍山淺草寺 1962 (Yushun Hosono, Brief History of Sosenji-Temple, Kinryuzan-Sosenji 1962)