Guardians of Temples and Shrines

In candis (ancient temples) within Java built between the mid-seventh and the fifteenth centuries, a grim face of monster is watching intruders from above the doorway.

This face of a monster known as “Kala’s head” in Java, must have originated from Kirutimuka (Skt) found in temples in India. “Kala's head” is a literal translation of “Kepala Kala” of the local language, but let us occasionally call it Kala’s face, because it is generally a thin sculpture in which only the front part of the head or face is carved.

What is the meaning of Kirtimukha which is defined in dictionaries and books as the Face of Glory? A legend is found in a Hindu book called Skanda Purna written in the 12-13th century India[1], [2].

“There was a very powerful king of the Daityas named Jalandara who had conquered all three worlds. At that time, Lord Siva, the supreme god or the controller of the creation, maintenance and destruction of all things, was away from the abode of heaven and intended to wed Parvati, his original wife who was reborn as the daughter of the king of the Himalayas. She was a glamourous beauty. Incensed with pride, Jalandara sent a monster, Rahu, as a messenger to Siva and contemptuously commanded the latter to give up his claims for Parvati’s hand, as Jalandara had misunderstood Siva as a beggar and thought he himself would deserve the lovely princess. When the messenger, Rahu, delivered the message to Siva, the great god became angry and shot out a terrible form from between his eye-brows. Although the terrible form with burning eyes and bristling hairs had an emaciated body which resembled that of Narasimha, the man-lion incarnation of Vishnu, he covetously ran up to eat Rahu, whereupon the latter prayed to Lord Siva to save him. Siva dissuaded the form from eating up Rahu, but the form complained to Siva of intense hunger and begged him for food. By Siva’s order to appease his hunger by eating his own flesh, the hungry form ate up not only his hand and arms, foot and legs but also his abdomen, chest and neck, leaving only his face intact.

Pleased with this, Lord Siva addressed the terrible face which had saved his honour that thenceforth it would be known as ‘Kirtimukha’. Further, he ordained that the ‘Kirtimukha’ should always remain at the doorways of Siva temples, and that whosoever failed to worship the ‘Kirtimukha’ would never acquire Siva’s grace. Thus, the ‘Kirtimukha’ has had a permanent place on the doorways of Siva temples.”

Thus, Kirtimukha is understood to be a head of a monster that is still alive, even though it has lost the part below its neck.

Besides the legend of Kirtimukha, the reason why Rahu had lost his body was told in another myth. Although the story was diverse in details according to sources[3], [4], [5], the substance would be roughly as follows.

“A long time ago in the days of the beginning of the world, gods and monsters worked together to churn the cosmic Milky Ocean in order to extract Amrita, the elixir that could bestow immortal life on all living things, from the bottom of the sea. When the pod of Amrita emerged, a scramble occurred. A beauty named Mohani came to arbitrate between them and when a proposal to distribute portions of Amrita at first to the gods was agreed, a monster named Rahu disguised himself as a god and joined the row of gods. Although he successfully sipped Amrita, his deceit was discovered by the Sun god and the Moon god. Mohani was an avatar of Vishnu. Then, Rahu was beheaded by a throw of sudarshana chakra, a Vishnu’s disc-like weapon with 108 edges. Although Rahu’s head and neck have had eternal life, his detached body to which the elixir had not reach became wilted. Rahu became the enemy of the Sun and Moon. Rahu only with his head transformed himself into a star to chase the moon and went up to the lunar orbit. Lunar eclipse occurred when Rahu put the moon into his mouth but moon could easily come out every time, as Rahu had no body (Hereinafter omitted).”

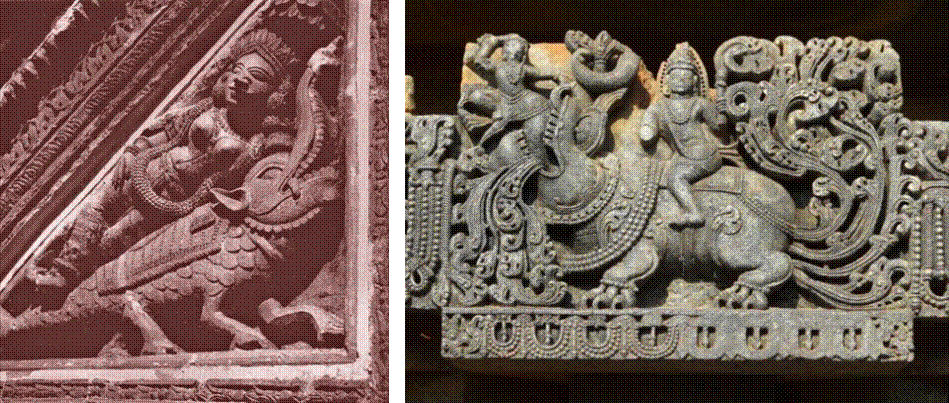

In the sculptures of Kirtimukha placed in the front of temples in India, both hands remains, each grasping a Naga, i.e., a serpent or a dragon.

Examples of Kirtimukha in India.

Left: A temple name unknown), Kathmandu. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kirtimukha#/media/File:Kirtimukha.Nepal1.JPG

Right: Patan Durbar Square, Kathmandu, wooden.

http://www.mountainsoftravelphotos.com/index.html

A strange monster depicted underneath the Naga in each side, Makara, is an aquatic animal that is said to be served as the vehicle of Ganga ma, the goddess of water, or Varuna, the god of sea, or to represent the insignia of Kamadeva, the god of love.

Although Makara was a word which meant a crocodile and yielded the Sanskrit word Mugger[6], the figures drawn were various, being similar to a fish with a trunk of elephant, a crocodile with a trunk of elephant, an elephant with a tail of peacock, and so on. In a paper[7] of a famous scholar of Javan archaeology, Dr. Stutterheim, it was postulated that the sign of “Goat-Fish [goat with a fish’s tail]” for the Zodiac Capricorn would have been grafted, giving rise to various images. Contrarily, it is written in many books that Makara did represent Capricorn in the Hindu zodiac.

Let us see the pictures of Makara in India and the continental Southeast Asia found on the Internet.

Left: A relief of Ganga Ma, Charbangla Temple, Bengal, East India (18th C.). http://www.harekrsna.com/sun/features/12-06/features501.htm

Right: A relief of Varuna, Hoysula Temple, Southwest India (1120-1160 AD). https://in.lifestyle.yahoo.com/photos/halebeedu-the-crown-jewel-of-hoysala-temples-slideshow/halebeedu-photo-1336120096.html.

Left: A relief of Makara. Sambor Prei Kuk Temple, Cambodia, Kampong Thom City (7th c.). http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mus%C3%A9e_Guimet_897_04.jpg. [Kampong Thom was the capital of the former Chenla kingdom.]

The woman in the first photograph must be the goddess Ganga Ma. She looks erotic in this particular example, despite that she is usually drawn in holy figures.

Benzaiten, a Goddess of Buddhism in Japan, is

considered to have originated from Ganga Ma, the Goddess of Water, found in the old

Indian holly book "Rigveda".

Both the men in the second and the third pieces at the Hoysula Temple and the Sambor Prei Kuk Temple, respectively, are obviously the god Varuna, although the figures carved are quite different.

For reference, the horse depicted in the relief of the Sambor Prei Kuk Temple is supposed to be the sacred horse Uchchaihshravas and, if so, the person who mounted the horse must be the god Indra.

Makara is often discharging a strange creature from, or swallowing it into her mouth. The creatures in the second and the third reliefs look human-like and lion-like, respectively, whereas the creature in fourth one is undoubtedly a Naga (serpent).

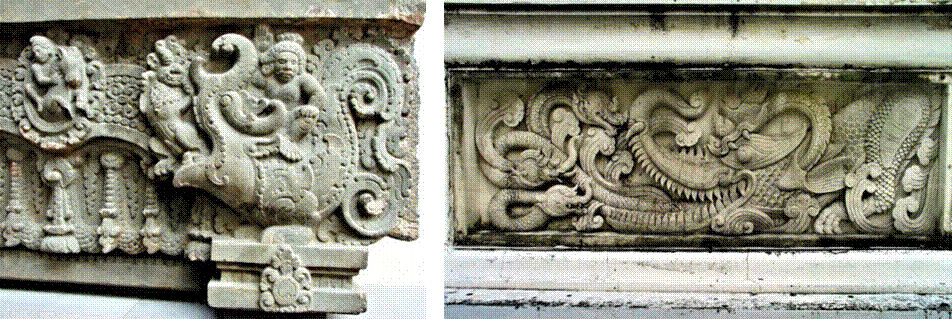

Although both Kala and Makara originated in Hinduism in India, it was adopted in Java not only in Hindu temples constructed by the Sanjayas in the 8th-9th century in Prambanan and other places, but also in Buddhist temples contemporarily built by the Sailendras, including Candi Kalasan to the east of the present-day Yogyakarta, Candi Sewu and Candi Plaosan at Prambanan Plain, the three temples at the Kedu Basin represented by Candi Borobudur and others.

As to be mentioned in the later part of this section, the Kala’s face was replaced with the one depicting a face of lion and the lion’s face in the 9th century at Loro Jonggrang Temple Complex, and the new motif was inherited, after the move of the royal capital to the East Java, in the Hindu or Hindu-Buddhist syncretic temples constructed in the 13-15th century during the Singasari and Majapahit eras.

The feature of Kirtimukha might remind one of the Gorgoneion which was once popular in Europe, especially in the Mediterranean areas, and the function to protect sacred places from evils were common, but the origins were different, the latter having been derived from the female monster Gorgon in the Greek mythology.

Left: A terracotta antefix Gorgoneion from Sicilia, ca. 490 BC, British Museum. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?partid=1&assetid=365199&objectid=463285.

Right: An Athenian black-figure pottery kylix with a Gorgoneion picture. 6-5th century BC. Held by Ashmolean Museum, UK. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Athenian_black-figure_pottery_cup,_6-5th_century_BC,_an_outdoor_symposium_(drinking_party)_beneath_a_vine_arbour,_around_a_Gorgons_head,_Ashmolean_Museum_(8400674085).jpg.

Bowl with a gorgon's head surrounded by a frieze of deer, lions, sphinxes and a siren Early Corinthian, about 610-590 BC. A collection of British Museum. Photographed by M. Iguchi, April 2017. (Added in March 2019)

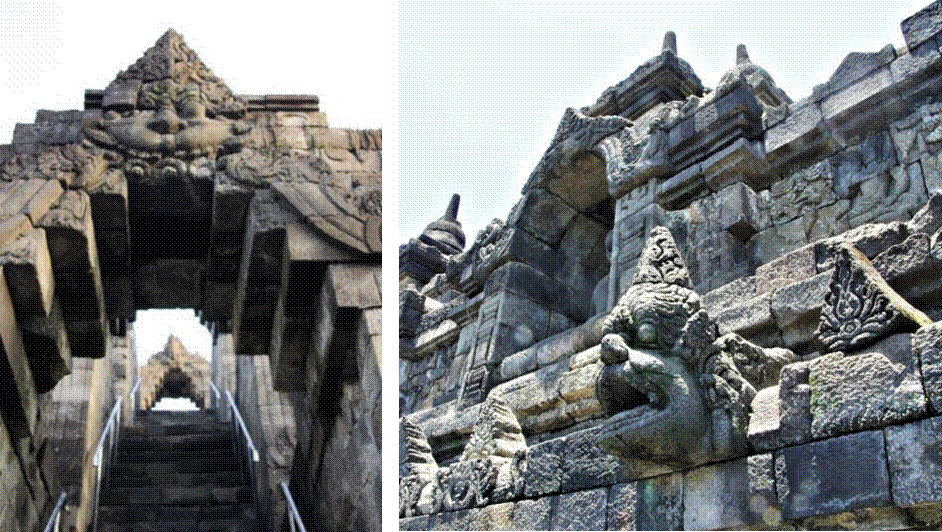

In Java, the Kala’s head on the lintel of the hall entrance temple or placed on top of the arch is, in many cases, linked to Makaras placed at the bottom of both left and side pillars, forming the so-called "Kalamakara motif". The famous example is the one on the arches, at Candi Borobudur, which have been placed on each terrace at the flight of stairs provided at the centre of four sides, leading from the ground to the summit. Since the progress of weathering is serious, let us borrow sharp photographs taken 100 years ago.

Left: Kalamakaras on the arches of Borobudur.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Candi_of_Indonesia#/media/File:COLLECTIE_TROPENMUSEUM_Poort_op_de_Borobudur_TMnr_10015959.jpg).The same photograph was adopted in the book of Stutterheim (below).

Right: Makara at the bottom part of Kalamakara (Judging from the incidental angle of light, this must be the one from another arch). Reproduced from: W. F. Stutterheim, Pictorial history of civilization in Java, Translated by Mrs. A. C. de Winter-Keen, The Java Institute and G. Kolff & Co., Weltevreden, 1926.

A photograph of the arches at Borobudur taken during the recent visit (June 2019) is added below.

Tripple arch gates at the stairs form the 1st, 2nd and 3rd terraces of Candi Borobudur (East side). Photographed by M. Iguchi, July 2019 (A composite of two separate photographs) (New).

In this arch, a pair of patterned bands that are rolled up from the tail of the Makaras, placed at the bottom of the pillars on both sides, are extended to the Kala’s head at the summit. The Kala’s face has no lower jaw exposing the row of teeth is similar to that of India but no bulge of cheek. The hair is bristled upward forming a triangular shape, unlike in the examples in India which had a little hair on both sides of his head. Since the inside of the wide-open mouth of Makara is not well observed in this photograph taken from the side, let us see it later in a different picture.

In Borobudur, a number of niches are located above the inner wall of corridors. Whether or not classified in the category of “Kalamakara motif”, the Kala’s head set on top of the verge of cusped gable of niches is also connected through bands to the Makaras placed at the end of the eaves.

In many temples in Java, Makaras are placed at the bottom of staircases, which lead from the ground to the hall, and the tails Makara extends obliquely upward to form the stringers. In Borobudur, there were some places where bold heads of Kala were found at the upper ends of the stringers.

Left: One of the niches placed above the inner wall of corridors of Candi Borobudur.

Right: A staircase with Kalamakara-like stringers at Candi Borobudur from the ground.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

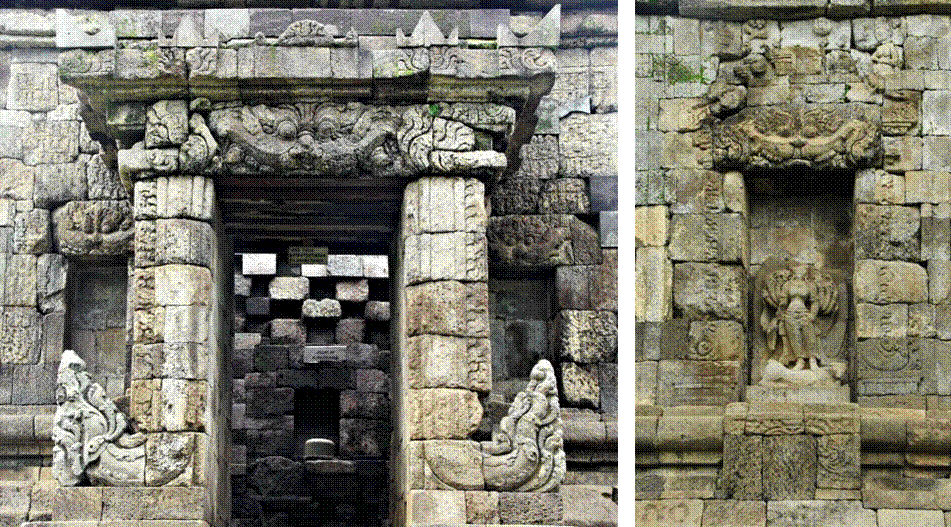

Temples with arch-type Kalamakara as Borobudur are rare in Java but other examples are found in the interior niches of Candi Plaosan, as will be described below. In general, the type of Kalamakara in which pillars with bands extending upward from Makaras and support the lintel with a Kala’s head is more common. Below are two examples from two candi built in Central Java in the 8-9 century.

Left: The front of Candi Plaosan (782 AD, Buddhist). Photographed by M. Iguchi, July 2006.

Right: The front of Candi Siva, the main temple of Loro Jonggrang Temple Complex in Prambanan Plain (generally called Prambanan Temple). Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

The pattern on the bands rolled up from the tail of Makara and linked to the Kala’s head in the Kalamakara does not seem to have been discussed much but I would like to agree with the theory[8] that it represented a Naga. In fact, the reliefs of temples in India with Kala’s head, Naga and Makara (seen above) suggest some relationship between the three entities, and the Makara in the relief Wat Suthat Temple, Thailand (also seen above), had a Naga in its mouth. Also, I remember an ornament on the fence of the outer corridor of the main hall in the Yogyakarta Palace, in which a Kala’s head is places in the centre and two serpentine Nagas were set on the left- and right-hand side with their tails directed to the centre.

The fence of the outer corridor of the main hall, Keraton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat, Yogyakarta.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2007.

(4) Overview of Kala’s face and Makara in Java

Candi Arjuna and Candi Gatotkaca among temples or temple complexes existing in three areas in Dieng Plateau are considered to be the oldest candis in Java, having been built in 650-730 AD as estimated by Dr. Soekmono[9], an authority of Javan archaeology. Whilst these candis in Dieng are somehow said to have been constructed by the Sanjaya Kingdom, the year when Sanjaya Harisdharma moved from the West Java to the Central Java was commonly considered to have been 732 AD, leading that the construction of Candi Arjuna and Candi Gatotkaca would have been earlier than the founding of Sanjaya Kingdom, if the theory of Dr. Soekmono was adopted.

According to “The genealogy of ancient Javanese royal families proposed” by the present writer(See, the different section), Since the kingdom existed in the 7th to the early 8th century in Java was the Keling Kingdom[10] which was reigned by King Kartikeyasingha (648-674)and inherited after his death by Queen Sima (674-695). Thus, it may be hypothesised that those who constructed candis in the Dieng Plateau, at least those of early times) were the people of Keling Kingdom.

After then until the 15th century, numerous candis were built in Central and East Java and several tens of them exist today in reconstructed forms. In West Java, there are a few relics of temples unearthed until today, such as Candi Bojongmenje (built around the 7th century in the era of Kendan Kingdom?[11]) and Candi Cangkuang (8th century), both mentioned in “Java Essay”, as well as Candi Batujaya Complex (constructed in the 5th-6th century in the Tarumanagara Era[12]), but they all were buried underneath the soil and destroyed to such an extent that no building shapes remained before they were excavated.

Let us see the Kala’s heads and Makaras ornamented in several candis in the Central and East Java.

Candi Arjuna (Dieng Plateau), Hindu, 650-730 AD

The first picture is a classic photograph of Kala’s face which was included in a Dr. Sutterheim’s book[13]. The Kala’s face has no bulge of cheek, unlike the ones in India, and the row of teeth is seen.

A Kala’s face of a candi in Dieng. Held by the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam. No. 60016337.

http://collectie.tropenmuseum.nl/Default.aspx?ccid=19395.

In the image of the front design of Candi Arjuna referred to on the Internet, it is seen that the Kala’s head on the lintel and the Makara at the bottom are linked to form a Kalamakara. The hairs of Kala forms triangle above the head. The features of Kala’s head at Dieng look more or less similar to those of Borobudur, being the prototype of the latter.

Although it is not clear in the photograph, convex objects seen at the top of the stringer of the staircase are probably Kala’s heads as seen in Borobudur. If so, the lintel with a Kala’s head and a Makara at Candi Arjuna, too, is supposed to be the original one.

Left: The front of Candi Arjuna, Duplicated from: http://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berkas:Candi_Arjuna_close_up.jpg.

Right-top: Kala’s head at the front entrance of Candi Arjuna; Right-bottom: The same at the front niche.

Partially duplicated from: https://lettersfromangelaa.wordpress.com/2013/11/15/111013-dear-van-banjarnegara/.

Candi Kalasan (Kalasan Village), Buddhist, <778 AD

A Buddhist temple, Candi Kalasan located in the east suburb of the present day Yogyakarta, must be no other than Candi Tara written in Kalasan Stone Inscription (778 AD) as “Teachers of the king of Sailendra asked King Panangkaran [of Sanjaya] to erect Candi Tara, i.e., the building of a statue of Dewi Tara, the temple, and monasteries.” Although the present precinct is not so wide, it is supposed to have formed a large temple complex with auditoria, libraries, quarters, kitchens, etc. In fact, the two-storeyed Candi Sari located about 500 metres away to the north is considered to have been an annexed monastery.[14]

Total view of Candi Kalasan. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

An interesting object is a relief on a large lintel above the Kala’s head of the west-side entrance in which an outer view of a building which is supposed to have been of this candi at the time of its inauguration is sculptured.

The lintel at the west-side entrance of Candi Kalasan. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

The Kala’s face at this candi has a round jaw, unlike the ones at Hindu temples in Dieng, while the feature of hairs bristling upward to form a triangle is the same to that of the latter. It is also noted that the Kala’s head in the Kalamakara of the entrance has arms, squaring the elbows and bending the wrists inward.

The Kala’s heads on the lintel of the front entrance of Candi Kalasan (Left) and on the upper part of the wall (right). Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

The Makara at the bottom of the staircase has an open mouth, and rod-like object with a snake-skin pattern (unidentified to the present writer) hanging down from the upper part and reaching to the head of a lion-like animal. The nose of Makara is bent above the head and its tip is rounded.

Left: Makara at the bottom of the staircase at Candi Kalasan. The stringer which should have been extended from the tail of Makara is lost.

Right: A Makara placed alone on the ground. This is supposed to be a part of the staircase of some other building.Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Numerous stone blocks of Kala’s heads, Makaras and other parts probably collected from other extinct buildings were seen behind the main hall, enabling me to have a close look. The Kala’s heads and Makaras among them looked similar with those of the main hall.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Top: A part of the collection of the stone blocks at Candi Kalasan.

Bottom:Example of Kala’s head in the collection of the stone blocks at Candi Kalasan. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

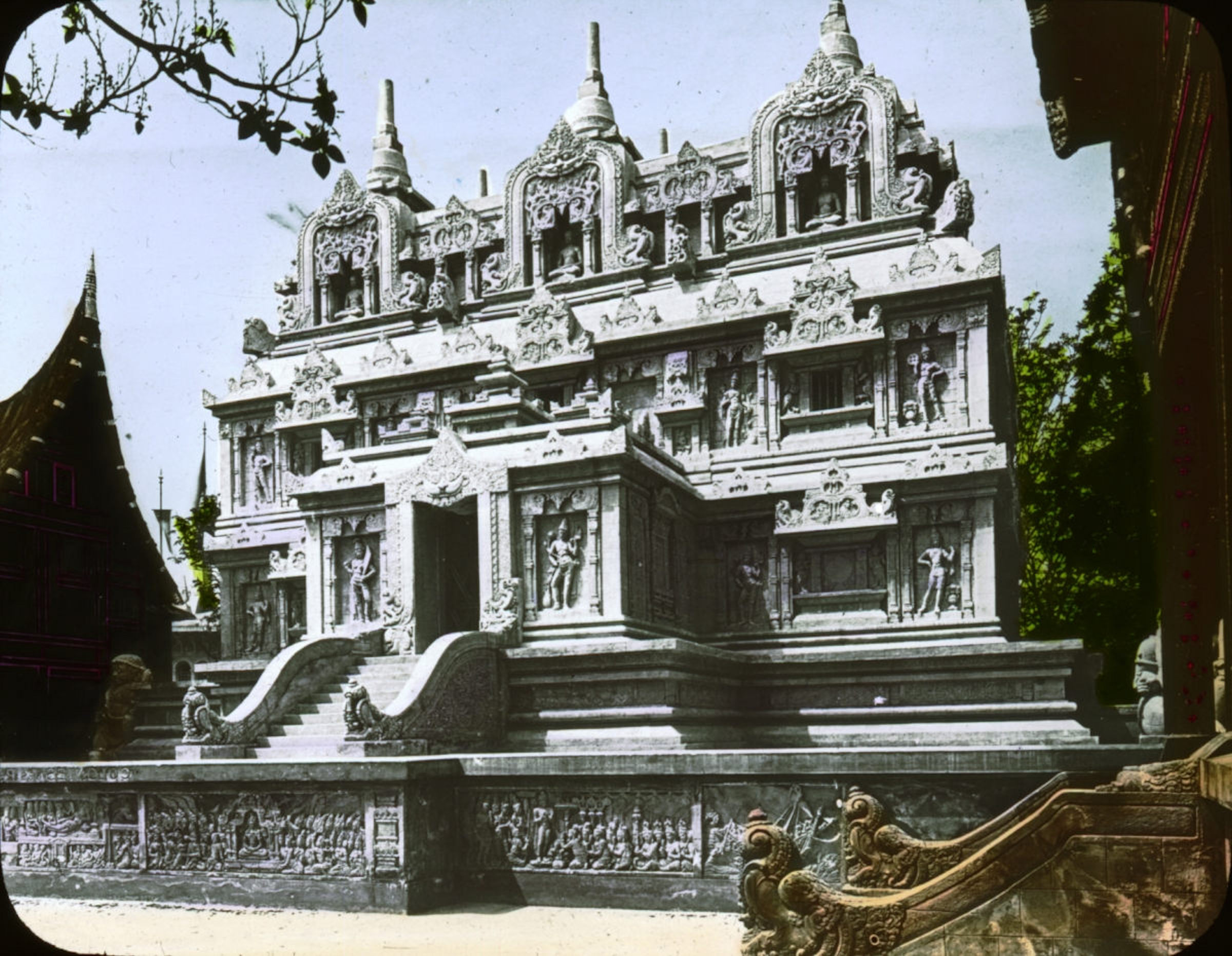

Candi Sari (Kalasan Village), Buddhist, <778 AD

This candi, located 800 m away to the north-east of Candi Kalasan, is considered to have been a monastery of the latter. The outer walls of the two-storeyed building are decorated with numerous sculptures of Goddess. Whilst the Kalamakara at the front entrance is the type consisting of two vertical pillars and a lintel, the niches inside the building are framed with an arch-type Kalamakara which looks similar to the arch gate of Candi Borobudur. Since the inauguration of Candi Sari was forty-odd years earlier than that of Borobudur, the arch gate of the latter might have been designed after the Kalamakara of this candi's nitches.

A reprica of Candi Sari was constructed at Paris on the occasion of Exposition Universelle 1900 as one of the three pavilions of the Dutch East Indies section. Such a luxurious spending can hardly be imagined today. This shows how the East Indies government was proud of historical remains in Java at that time (Added October 2019).

Total view of Candi Sari. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (New).

A replica of Candi Sari constructed at Paris on the occasion of Exposition Universelle 1900 as one of the three pavilions of Dutch East Indies section (Wikipedia). The building on the left-hand side must be modelled after a Rumah gadang (Big house), a specific spired roof house of Minankabau, West Sumatra, in which kinsmen members lived.

Left: Kalamakara at the front entrance of Candi Sari. Right: Arch-type Kalamakara at a niche inside Candi Sari. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (New).

Candi Sewu (Prambanan Plain), Buddhist, ca. 782 AD

Candi Sewu is regarded to be a temple mentioned in Kelurak Stone Inscription as “King Indra gave an order to construct a sacred Buddhist temple to house the statue of Manjusri who held the wisdom of Buddha, dharma [law] and sangha [priests]” This candi had been heavily ruined, as the Kala’s head at the restored main hall lacks its upper part. The condition of side halls were similar. The Kala’s heads in this candi had a sculpted face, deeper than former ones and in the lintel of a side hall two monks who looked like hermits with pressed palms were carved on the left- and right-hand side of the Kala’s face. The Kala’s faces in this candi showed teeth but had no jaw.

Left: Front view (north side) of Candi Sewu Temple Complex. Right: Kalamakara at the entrance of Candi Sewu Main Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (Replaced).

Kala’s head of one of the side hall of Candi Sewu. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

The Makaras at the entrance of the main hall as well as those below the staircases remained in relatively good condition. The Makaras in this candi were more or less similar to those in Candi Kalasan but the creature in the mouth was not lion-like, squaring elbows and sitting cross-legged.

In this candi, I saw Makaras, in which a hole was bored in their mouth, above the outer edges of upper layers. I learnt that this type of Makaras which were also seen in some other candis were not simple ornaments but functioned as gargoyles.

A pair of Makara at the bottom of stringers at Candi Sewu. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Left: A Makara of Kalamakara at the entrance of the main hall, Candi Sewu.

Right: A Makara on the outer edge of the upper layer, Candi Sewu.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Candi Mendut (Kedu Basin), Buddhist, ca.782 AD

Candi Mendut is a candi built by the Sailendras in Kedu Basin, prior to Candi Borobudur, being estimate to have been inaugurated (in ca. 782 AD) around the same period as of Candi Sewu. A magnificent candi with an 8-metre square and 40 metre tall main hole, standing on a 13.7 metre basement, houses a large Shakyamuni Triad and the walls in the left, right and rear sides are decorated with extraordinarily large reliefs of goddess Tara. No Kalamakara is seen in the entrance, presumably having been lost before restoration.

The Makaras at the bottom of the staircase is similar to those of Candi Sewu. On the wall of basement are provided Makaras for gargoyle, the design of which looked being similar to those at the staircase.

A view of north-west front of Candi Mendut. Photographed by M. Iguchi, May 2009.

Makara on the wall of the basement of Candi Mendut. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012.

A pair of Makaras at the bottom of stringers of Candi Mendut. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012.

Candi Borobudur (Kedu Basin), Buddhist, 824 AD

Candi Borobudur, the most superb temple in Java constructed in 824 AD at the heyday of Sailendra Kingdom by King Samaratungga, is gorgeously decorated. Besides Kala’s head on the arch, niches above the inner wall of corridor and the stringer of staircase from the ground, mentioned above, bald Kala’s heads were found at the foot of staircases between layers.

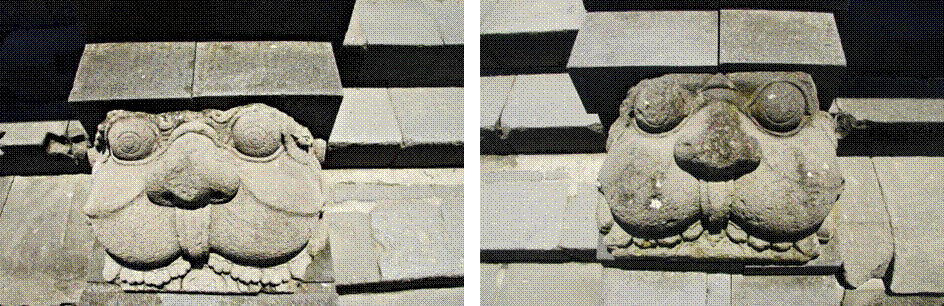

More remarkable ones were three dimensional sculptures of Kala’s head, placed as gargoyles at the upper edges of the basement, which clearly showed the details features of the face and profile unseen in the two-dimensional Kala’s faces. Such a steric Kala’s head was not found in other candis that I had ever visited.

The hairs of Kala on the arch looked shorter, or the height of the triangular outline lower, than those of Kalasan.

Total view of Borobudur shrouded in the morning mist. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2007.

Bald Kala’s head at the foot of staircase between layers. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Left: Kala’s face on the arch of Candi Borobudur. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2007.

Right: Steric sculpture of Kala’s head placed at the upper edge of the Candi Borobudur’s basement. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012.

In Borobudur, sculptures of Makara were found not only at staircases but also independently at the corners of the basement. The features of Makaras in Borobudur were similar to those in Kalasan.

Left: A Makara at the bottom of stringer of staircase from the ground in Borobudur.

Right: A Makara set at the corner of the basement in Borobudur. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012.

Candi Pawon (Kedu Basin), Buddhist, Early 9th Century

This small but elegant candi located between Candi Borobudur and Candi Mendut is believed to have been built by Princess Pramodawardhani, daughter of King Samaratungga (reigned 812-833 AD), to enshrine King Indra (c. 782-812 AD). Above the lintel of the entrance is found a Kalamakara which is similar to that of Borobudur, viz. above the niches on the corridors (Added October 2019).

Front view of Candi Pawon. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (New).

Kalamakara above the lintel of the entrance of Candi Pawon. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (New).

Candi Plaosan (Prambanan Plain), Buddhist, 820s AD

Candi Plaosan, a Buddhist temple constructed in 820s contemporarily with Borobudur by Sri Kahulunan (Roya title of Princess Pramodawardhani) of the Sailendras, consists of two, two-storeyed buildings, Lor and Kidul. The Kala’s head in this temple is significantly different from the traditional one, not only as the height of the triangular outline of hairs is much lower but also as the mouth is clearly sculpted and the tongue is extruded. Just for reference, Candi Plaosan was aimed at the abode of goddess Tara[15] so that the walls of the buildings are covered all over by reliefs of the goddess.

The feature of the Makaras in Plaosan is similar to those of Borobudur.

The niches inside Candi Plaosan Kidul were decorated with the arch-type Kalamakara (This line added in October 2019)

Total view of Candi Plaosan-Lor. Photographed by M. Iguchi, May 2008.

A Kala’s head of Candi Plaosan-Lor. Photographed by M. Iguchi, May 2008.

Makaras at the bottom of the stringer of Candi Plaosan-Kidul. A candi seen in the distance is Candi Plaosan-Lor. Photographed by M. Iguchi, May 2008.

At Candi Plaosan Kidul, not only the front entrance but also the nitches inside the building was decorated with Kalamakara, but the niches were empty, as same as those of many other candi around the area. The reson was because in 1885 an association to collect relics in Central Java for arcaeological study was formed and many of them were gathered at Yogyakarta[15a] Having been informed that Biddhist statues which had existed at Chandi Plaosan were stored an the Resident's Residence (Now called Gedong Agung) within the city of Yogyakarta, I visited there but the premise was not open for public. The photographs below have been dulicated from the web pages of The New York Public Library.

Left: Kalamakara at the front entrance of Candi Plaosan Kiduli. Right: Arch-type Kalamakara at a niche inside Candi Plaosan Kidul. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (New).

Statues of Tara and Manjusri from Candi Plaosan in the Resident’s House (Now

Gedung Agung). Whichever Plaosan-Lor or Plaosan-Kidul is unknown. Duplicated

from The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/

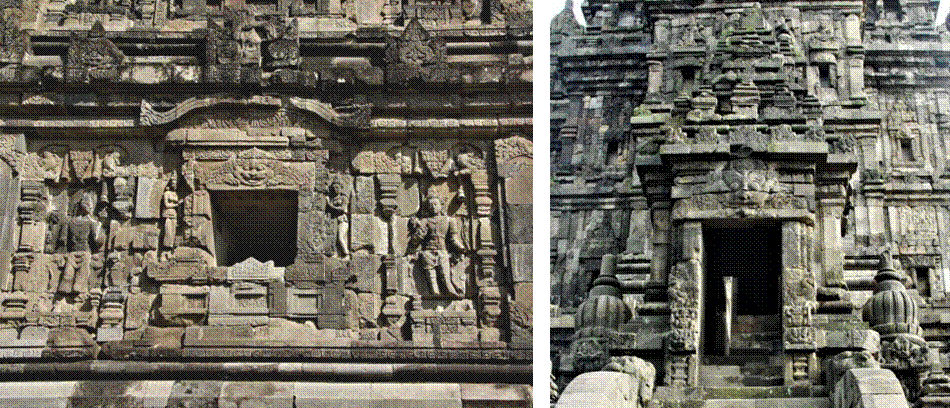

Candi Loro Jonggrang (Prambanan Plain), Hindu, 856 AD

Candi Lolo Jonggrang (generally called Prambanan Temple) constructed one kilometre south of Candi Sewu by the Sanjayas in 856 AD during the reign of Prince Pikatan who married to Princess Pramodawardhani of the Sanjayas is a large temple complex, occupying an area of 390 metre square. The main temple, Candi Siva standing in the depth of the inner precinct of 225 meter square is as large as 34 metre wide and 47 metre tall: the whole wall is adorned with fine reliefs and numerous steric sculptures of various designs are placed on the basement and every layer up to the summit. Seven candis of middle and small sizes which surround the main candi shows similar gorgeous appearance.

As to the reason how the Sanjayas, who before then built only moderate- and small-size candis was able to construct such a magnificent temple complex, I would consider that they owed much to the wealth of Pramodawardhani which she had inherited from the rich Sailendras.

Left: Total view of Candi Loro Jonggrang Temple Complex at Prambanan. Right: Kalamakara at the entrance of Candi Loro Jonggrang. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2019 (New).

The Kala’s face in Candi Loro Jonggrang is quite different from the traditional ones, in Candi Kalasan and Candi Borobudur, which had imitated the Kirtimukha of India, and said to have represented the face of lion. In fact, triangular ears are seen above the face. How did the change come about? I would speculate that the designer or the artist, who were shown pictures of lion by visitors from India, invited for the inauguration of Candi Borobudur or the construction of this candi, thought the king of beasts was more suitable for the guardians of temples than the ‘imaginary’ monster’.

This Kala’s face with this feature was common for Kala’s heads of niches for ApsaraTrios and Lokapala (guardians for eight directions) also in other cadis around the main candi.

Left: Kala’s head on the lintel of front entrance, Candi Siva.

Right: Kala’s head on the lintel of front entrance, Candi Nandi. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Left: A niche for Apsara Trios, Candi Siva. . Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012.

Right: Niches for Lokapala, Candi Siva. . Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

This type of face may be better called Lion’s face, rather than Kala’s face, but let us continually use the latter for the sake of convenience.

The Makaras at the bottom the stringer were of typical design, having a wide open mouth in which a rod-like object hang from the upper part and reached the head of lion on the inside jaw. Makaras of different designs, at least two kinds, which must have functioned as drains, were seen on the upper part of the main candi.

Makaras at the bottom the stringer, Candi Siva. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Makaras for drains on the upper layers of Candi Siva. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

The time of Candi Loro Jonggrang’s construction was highest point in the history of candis in Central Java and only small scale candis were built afterwards. Let us next see Candi Barong which remains in relatively good conditions.

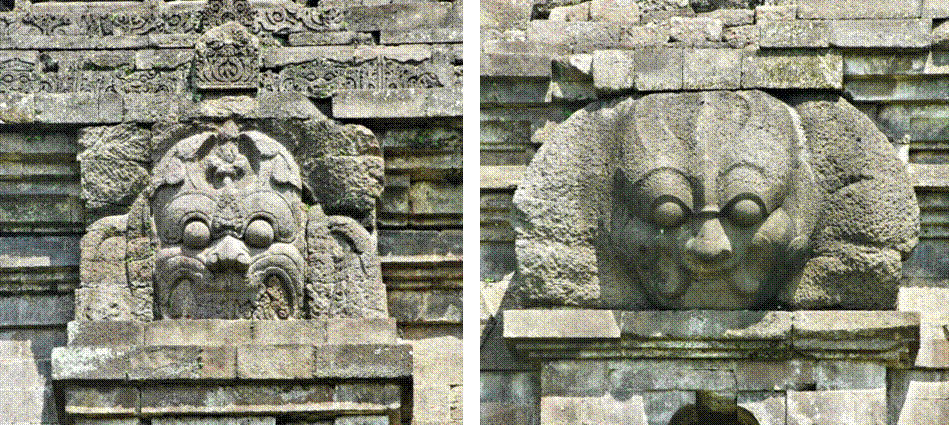

Candi Barong (Prambanan Plain), Hindu, Late 9th c.

Candi Barong is a Hindu temple which is supposed to have been built in the late 9th century in a southern area of Prambanan Plain. The Kala’s head at the alcove on the side wall of the main temple (photographed) looked to have inherited the lion’s face of Candi Loro Jonggrang but had a large mouth in which the row of teeth and fangs were exposed. The one at the front entrance was similar. This candi had a front gate and the Kala’s head on its lintel was more similar to that of Candi Loro Jonggrang.

Makaras of Kalamakara at the entrance and the alcove of the main hall as well as the front gate were simple works, as their front faces were just flat with no carvings.

Total view of Candi Barong. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

The upper part (Left) and the lower part (Right) of Kalamakara on the side wall of the main temple of Candi Barong. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

The upper part (Left) and the lower part (Right) of Kalamakara on the front gate of Candi Barong. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

With regard to the human figure below the Kalamakara on the main temple’s side wall, that looks to be supporting the ceiling, let me mention in the next section, “Atlas”.

The history of ancient kingdoms in Central Java ended in 929 AD when Mpu Sindok moved the capital to East Java. The Isyana Kingdom which he created left no vestiges. Kediri Kingdom founded by King Airlangga does not seem to have been active in the construction of religious facilities, notwithstanding its economic prosperity, although the kingdom greatly promoted art and literature, as we see their works today. In fact, not much relics remains today, except the ruin of the terracotta-made Candi Gunung Gangsi and Candi Belahan, substantially a bathing place, both located, in the suburb of Pasuruan. (The latter is known as the site where a famous sculpture of Airlannga mounting Garuda was discovered.) The construction of candis revived in Singasari Kingdom founded by Ken Arok in 1222 around the present-day Malang.

Candi Badhut built in 760 AD in Malang, 200 years earlier than the Mpu Sindok’s move to the east, by Kanjuruhan Kingdom is an exception. With regard to the royal lineage in the 8th-9th century Java, while the two-dynasty theory which assumed the coexistence of the Sanjaya and the Sailendra kingdom, proposed by Dr. de Casparis, is nowadays widely accepted and the single-dynasty theory in which the two families were integrated receives little support, the view that the third dynasty, Kanjuruhan did exist around that time[16] is noteworthy and important.

Chand Badhut (Malang), Hindu, 760 AD

Small in size though, Candi Badhut has an elegant appearance with a Kalamakara, at its entrance that resembles the typical ones seen in those in early candis in Central Java. The feature of the Kala’s face is also similar, although it lacks the top part. Since Gajayana (alias Limwa), the founder of Kanjuruhan Kingdom and the constructor of this candi, was a great-grandson of king Kartikeyasingha and Queen Sima (See, “The genealogy of ancient Javanese royal families proposed” by the present writer in the different section), it would not be unreasonable to assume that he had imitated the design of Candi Arjuna and other candis constructed in Dieng Plateau during the era of his great-grandparents.

Total view of Candi Badhut. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Kalamakaras at the front entrance (Left) and the alcove on the side wall (right) of Candi Badhut. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Candi Kidal (East of Malang), Hindu, 1248 AD

The front design of Candi Kidal, the oldest candi in the Singasari era, built in 1248 as the mausoleum of the second king, Anusapati, was significantly changed 250 years after the end of the Sanjaya era in Central Java. Although a Kala’s head was placed on the lintel of the front entrance, it was not a part of Kalamakara, as no Makaras were set at the bottom of pillars.

Although the Kala’s face was a lion’s face with ears as first adopted in Candi Loro Jonggrang, the eyes were bulging, cheekbones were convex and four fangs were distinguished.

There were two Makaras at the foot of the staircase but no creature was found in the mouth.

Total view (Left) and Kala’s head (right) of Candi Kidal. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Makara at the foot of staircase at Candi Kidal. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015

For reference, Anusapati was a posthumous son of Tunggal Ametung, the former husband of Ken Dedes before she became the consort of Ken Arok. Anusapati assassinated Ken Arok and became the king (1227-1248).

Candi Jago (East of Malang), Hindu-Buddhist-Tantric, 1280 AD

Candi Jago was originally constructed in 1268 -1280 AD as the mausoleum of the 4th king, Wisnuwardhana, but considered to be modified in 1343 in the form of tantrism. This candi was miserably ruined to such an extent that the restoration above the 3rd layer was impossible. Reliefs which covers the whole walls are marvellous but they are serious weathered.

Three Kala’s head placed on the ground of the precinct with some other stone sculptures is as big as the height and width measures 50-60 centimetres, suggesting the largeness of the original building. The features of the Kala’s head were more or less similar to those of Candi Kidal. No Makara was found in this candi.

Total view of Candi Jago. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Kala’s heads placed on the ground of Candi Jago. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Candi Singosari (North suburb of Malang), Hindu-Buddhist-Tantric syncretic. 1229 AD

The construction of Candi Singosari is considered to have been commenced during the time of the 4th king, Kertanegara but stopped by the death of the king in 1292, by the rebellion of Jayakatwang, as the carving of Kala’s head in the second layer is complete but the one in the first layer is undone. The walls and staircases are in the state of stone work with no decoration or sculpture.

At the periphery of the candi building were some collections of stone statues but no Makara was there. The Kala’s face was significantly modified and a large moustache that bent downward was added.

Candi Singosari originally formed a large temple complex with other structures related to Buddhism and Tantrism. They included Candi Putri from which the famous statue of Prajnaparamita, presumably modelled after Ken Dedes, was found but only the main temple remains today. According to the caretaker, the site of Candi Putri is of use for an ‘Islamic’ mosque.

Total view of Candi Singosari. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Kala’s heads at the first layer (left),and second layer (right) of Candi Singosari. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Collection various stone sculptures placed in the precinct of Candi Singosari. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

In 1293 AD, the centre of kingdom of East Java was moved to the present-day Trowulan in the middle basin of Brantas River when Raden Wijaya founded Majapahit Kingdom. At that time, people had high ceramic technologies and applied beautiful bricks of precise sizes for many buildings in the city as well as the lining of a huge reservoir.

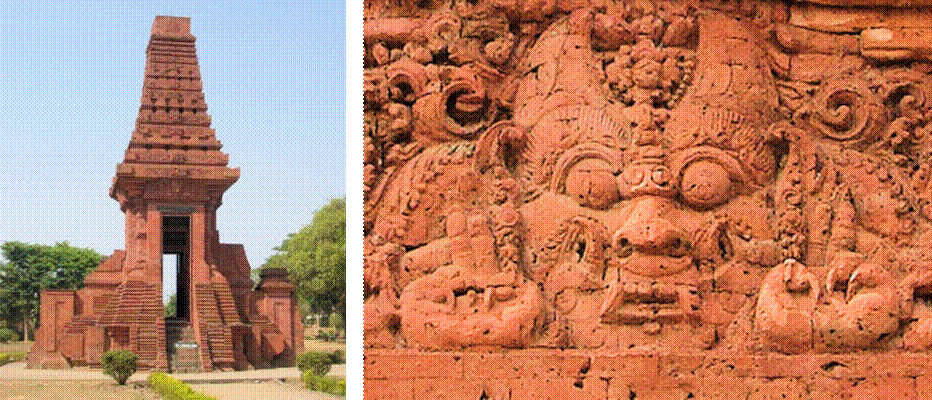

Candi Bajang Ratu (Majapahit), 14th c.

The only Kala’s head that I saw in Trowulan was at Candi Bajang Ratu which was actually not a temple as its alternative name, Gapura Bajang Ratu, meant Bajang Ratu Gate. The Kala’s face was a loin’s face similar to those of Singasari period.

In the old city area, there were to more distinguished structures, Candi Brahu and Candi Tikus. The former is supposed to have been a charnel house or repository of ashes for royal families whilst the latter was obviously a bathing pool. Thus, there was no temple in the city. It could be possible that important religious ritual were conducted at Panataran, 70 kilometres to the south.

Candi Bajang Ratu, a brick-made gate in Trowulan, the former capital of Majapahit (left) and the Kala’s head on the gate (right). . Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006.

Candi Brahu (left) and Candi Tikus (right) in Trowulan, the former capital of Majapahit. Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006.

Panataran Temple Complex (Panataran, North of Blitar), Hindu-Buddhist-Tantric, 14th c.

Candi Panataran, constructed during the era of the 3rd Queen Tribhuwana Tunggadewi (Mother of Hayam Wuruk, 1328-1351) in the developing period of Majapahit has a number of buildings in a vast area of 1.5 hectare, having had a status of candi negara (the state temple), but today the main temple retains only the three-storeyed basement. Since the syncretism of Hinduism, Buddhism as well as Tantrism was matured, many statues of dvarapala (guardians modelled after Rakshasa in Java) which was intrinsic to Buddhism were placed in the precinct..

As far as I had looked around, Kala’s head was found only above the entrance of Candi Angka Tahun which, although called Dated Temple in English, literally means a temple with the (sign of) year, as a plate with carving of letter to indicate 1291 Saka (1369 AD) is put above the lintel of the entrance. .

The Kala’s face was a lion’s face as of Candi Kidal and Candi Singosari of Singasari Period. No Makara was found underneath the pillars of entrance or at the foot of the staircase of this candi or elsewhere in the wide precinct.

Kala’s head above the entrance of Dated Temple at Panataran. A panel to show the year 1291 Saka is seen on the frame of the entrance. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Candi Sukuh (West slope of Mt. Lawu), Hindu, 1437 AD)

Around the turn of the century from the 14th to the 15th, Majapahit Kingdom became weakened due to the internal strife for the succession of the throne, allowing Moslems not only to control the port towns on the Java Sea but also to propagate their religion in inland areas. Candi Sukuh was located in a remote place of 900 metres from the sea-level in western hillside of Mt. Lawu probably because Hindus were cornered by Moslems.

This Candi is known for various sculptures, namely erotic ones, but the most characteristic feature is the shape of the main temple which looks like Mayan Pyramid[17]. In front of the approach was a solid stone gate and underneath the lintel of which was a Kala’s head. The head was actually a lion’s head that was similar to those seen in candis around Malang and Panataran and had a unique crown on it.

Left: Gate of Candi Sukuh. Duplicated from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gate_with_Kala,_Candi_Sukuh_1223.jpg .

Right: Kala’s head on the gate. . Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006.

Let us summarise the points.

(i) The history of temples in Java commenced in the mid-7th or early-8th century when a number of candis were built in Dieng Plateau.

(ii) As a guardian of temple’s entrance, Kirtimukha modelled after a monster derived from Hindu myth in India was adopted. Kirtimukha was called Kepala Kala (Kala’s head).

(iii) Kala’s head was adopted not only in Hindu temples but also Buddhist temples built in 9th-10th century by the Sailendras.

(iv) Kala’s face was replaced by lion’s face in the mid-9th century in Candi Loro Jonggrang constructed by the Sanjayas, and the lion’s face was inherited candis in East Java built after the 13the century..

(v) Kala’s head combined with Makara, a mythological sea monster, and Naga, both introduced simultaneously from India) and a unique motif called Kalamakara was created in Java to decorate the entrance of candis. In East Java, Makara was removed from Kalamakara.

(vi) Makara was also placed at the bottom of the stringers of staircases and, as gargoyles, at the upper parts of candis.

(vii) Makara almost disappeared in East Java. The only place at which Makara was seen was the foot of staircase of Candi Kidal built in the early Singosari period, but no such creatures as lion existed in the Makara’s mouth.

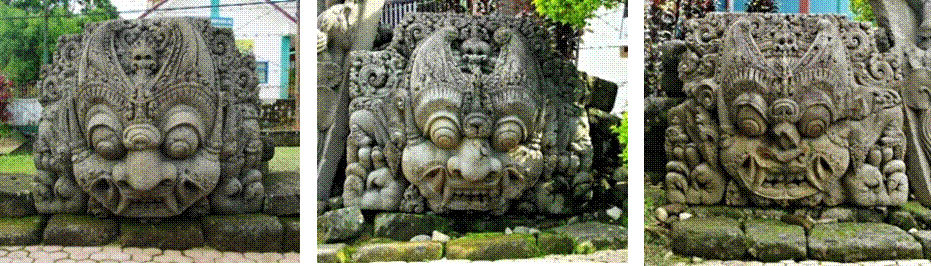

(5) Sculptures in the collection of Penataran Museum

Around the present-day city of Blitar are sites of many old candis of small candis, including Candi Sawentar mentioned in Java Essay, besides the gigantic Candi Panataran. The history of Penataran Museum in Blitar dated back to 1866 when relics found around the area was collected in the governor’s office. Now, the museum holds almost 300 statues, such as of Three-faced Siva, Durga and Ganesha, Dwarapala (Vajradhara) as well as Makara.

Examples of collections in Penataran Museum. (From the left to right) Three-faced Siva, Durga and Ganesha. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Statues of Makara (top-left, top_right, bottom-left) and a creature holding dwarf (bottom-right) in Penataran Museum. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

Many of Makaras in the museum were the kinds for gargoyle with a whole perforated in the lower part, but had no elephant’s nose above their head, unlike those seen in Central Java. Also, there were a few pieces of gargoyles which looked like a human-like creature holding a dwarf.

The fact that Makara was omitted in the candis in East Java is widely accepted, the only exception being the Makaras which I saw at Candi Kidal. Why so many Makaras were found around Blitar is a question.

Having seen a photograph of Kala’s head in Penataran Museum, that I had missed during my visit, I was surprised by its design rather that the fact that had existed. It was not the lion’s head but reminded me of the Kala’s heads in Central Java, especially those of early days in Candi Arjuna in Dieng Plateau.

Kala’s head in Penataran Museum.

Reproduced with permission from http://www.bocahblitar.com/2013/12/museum-penataran.html.

It is a mere speculation of mine but could not it be possible that candis had existed around Blitar in early times before the era of Sailendra Kingdom in Central Java? It is considered that Kanjuruhan Kingdom founded in 743 AD with its capital around the present-day Malang had a territory that extended to the areas of the present-day Kediri to the west and southwards[18]. In Carita Parahiyangan[19], it is written that among kings whom Sanjaya conquered during his eastern campaign was King Isora of Blitar. It could be possible that the King Isora’s kingdom was one of the “28 kingdoms under the control of Gajayana (Ki-yen, 吉延) of Kanjuruhan (Pulukasi, 婆露伽斯)[20]” described in the Chinese New Book of Tang.

With regard to Dwarapala (Vajradhara) seen in the Penataran Museum, let us discuss in a separate section.

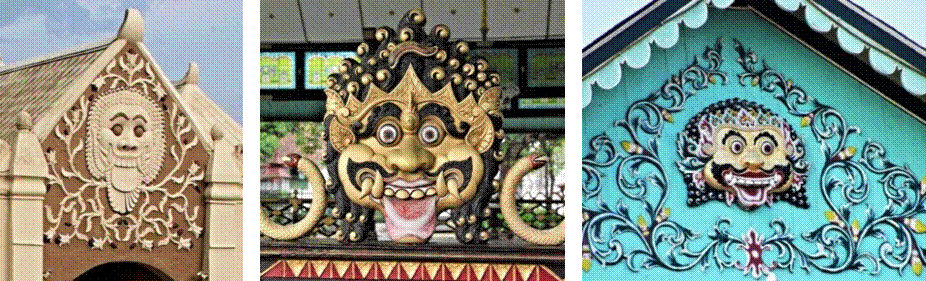

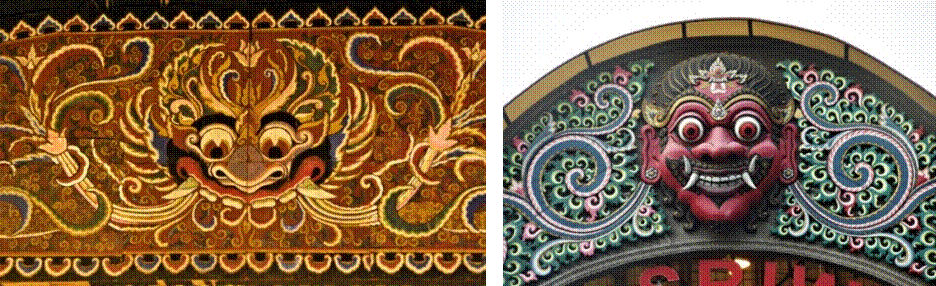

(6) Kala’ faces in modern palaces or other buildings

The religious map of Java was repainted in the late 15th century when the Islamic Demak Kingdom emerged in 1473 and accordingly Majapahit Kingdom perished. In the New Mataram Kingdom that was founded one century later and to continue to date, the old traditions of Java has been revalued as evidences are seen in Kala’s head of Hindu origin and Dwarapala (Vajradhara) of Buddhist origin placed anywhere in the palaces of Surakarta (solo) and Yogyakarta. Let us see some pictures, the designs of which are various, leaving aside the details.

Left: Kala’s face on the wall of an inner court in Taman Sari Royal Villa, Yogyakarta, Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2007.

Middle: Kala, s face on the fence of the Large Hall in Yogyakarta Palace. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2006

Right: .Kala, s face on the gable of Yogyakarta Palace. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2007.

Left: Kala‘s face on the curtain of Wayang Theatre in The Royal Sriwedari Park in Solo. Photographed by M. Iguchi, May 2009.

Right: Kala‘s face on the arch to the same park. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

(7) Kala’s head on the back of a Ganesha statue

Having been informed that a unique Kala’s head carved on the back of a Ganesha statue[21], not devised in a temple, exists in Tuliskriyo Village in the suburb of Blitar, I have paid a visit. When I passed a narrow path beside a signboard of “Ganesha Boko”, was a Ganesha statue of 1.5 meters tall was found underneath a roof in a plot of five metres square. Ganesha in the form of an elephant, is a son of Lord Shiva and his consort, Parwati, and said to be a deity who prevents all difficulties and dangers. As usual the statue had a broken tusk, a cup of skull, a hatchet and a duster to get rid of flies in his four hands. On his back was a carving of Kala’s face, or lion’s face, which was common after first appeared in Candi Loro Jonggrang. In fact, the letters carved on the pedestal indicated the year 1161 Saka (1239 AD) that was the era of King Anusapati of Singasari Kingdom. The part below the Kala’s face looked like the back of Ganesha, not the body of Kala. The Kala’s face is assumed to have been placed to protect the Ganesha, but such one has not been found elsewhere else.

According to the caretaker lady, it was discovered on the opposite dry riverbed of Brantas and moved here some decades ago. She also told that a small statue used to be in the side of the Ganesha but was stolen about fifteen years ago, pointing a concrete-made pedestal.

Ganesha Boro in the suburb of Blitar. Front (left) and back side (right). Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2015.

(8) Onigawara - Ridge end tiles with the face of ogre in Japan

When I was reviewing my album of photographs taken at Todaiji Temple, Nara, I was amazed to have realised in a piece of picture that the face of a huge ridge-end tile of about two feet height placed in a offhand manner with no panel in the Great Buddha Hall, behind the statue of Vaisravana (an deity to guard the north-east corner) was quite dissimilar to those faces of ogre with a pair of horns on the ridge-end tiles that are commonly seen at other temples and private houses elsewhere in Japan, reminding me of a Kirtimukha or Kala’s head in Java. When I revisited there and asked a clergyman in the office for issuing red stamps, he told me to visit the ticketing and information office. The priest who kindly received me said, “It is an imitation of a relic discovered at the site of the auditorium that had once existed behind the Great Buddha Hall.”, and took me to the temple’s library. A librarian spared her time to sort out about a dozen of relevant books and documents but no description about the unique motif of the tile was found. She told me the unearthed real tile must be held in the Todaiji Museum. In the museum, the original tile was not open for public but a curator show me a picture in a book, “The Precious treasures of Todaiji Temple”, that gave me a clear image.

Ridge-end tile from the site of extinct auditorium, Todaiji Temple.

Left: Imitation, placed behind the statue of Vaisravana in the north-east corner in the Great Buddha Hall, Todaiji Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, October 2014.

Right: Real piece. Duplicated from: Tobu Museum, The Precious treasures of Todaiji Temple, Asahi Shimbun Publications 1999).

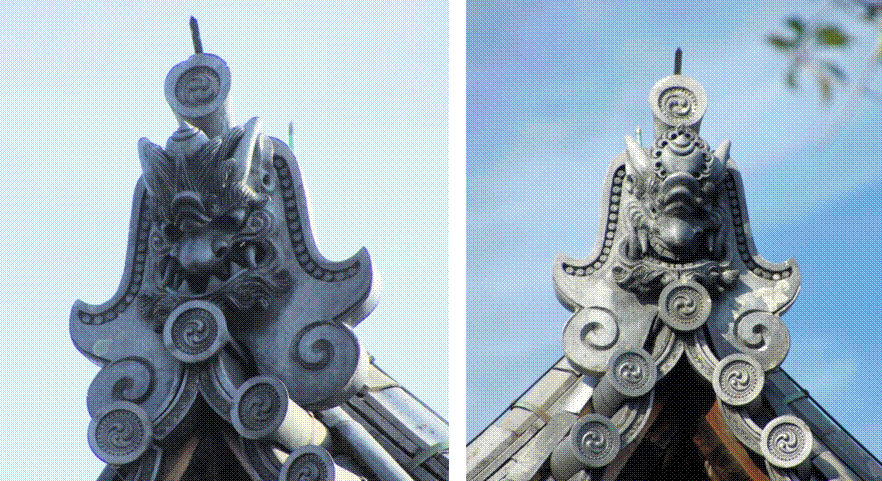

The young female curator told me “The Great Buddha Hall was burnt twice in the past. The present Hall was rebuilt in 1691 AD in Yedo Era and the ridge-end tiles of contemporary design were used. Nevertheless, ancient ridge-end tiles should remain in Tengai-gate (轉害門) at the west edge of the precinct.” At the gate, the viewing angle was limited as the space in both the left- and right-hand side was pretty narrow, but the ridge-end tiles looked different from those of later times. While I was walking around the east hill in the vast precinct of the temple, I found a ridge-end tiles that were much smaller but resembled the relic from the extinct auditorium at the roof of Sangatsu-do (alias Hokke-do). Then, I saw similar ones at a small hut which was supposed to have been a storehouse located near-by in front of Nigatsu-do, i.e., famous for the Water-taking ritual. These buildings in the peripheral areas must have been safe from the past conflagrations.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Ancient Onigawaras remaining in the peripheral buildings in the Todaiji Temple Complex at Tengaimon (top-left), Sangatsudo (top-right) and a hat in front of Nigatsu-do (bottom-left), and new Onigawara at the Great Buddha Hall (bottom-right). Photographed by M. Iguchi, November 2014.

When I visited Nara-Kyoto area again, I found similar onigawaras at the ridge of the bell tower of Gansenji Temple (built in 729 or 749 AD), Kidzugawa, Kyoto Prefecture, and the corner ridge of the Golden Hall of Toshodaiji Temple (built in 759 AD), Nara.

Onigawaras in the corner ridge of the Golden Hall of Toshodaiji Temple (left) and in the bell tower of Gansenji Temple (right). Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2015.

Then, how was the design of ridge-end tiles in earlier times before Todaiji Temple?. Having read in literature that the relic of tile with a lotus-flower motif discovered at the cite of extinct Wakakusa-garan building to the east of the Nandai-mon (Great South Gate) of Horyuji Temple has been reproduced and put on the roof of Daizo-hoin (lit. Large treasure house) built in 1998, I paid a visit. Indeed, a fresh ridge-end tile on which nine lotus-flowers were arranged was shining with blue sky in the background.

.jpg)

Ridge-end tile on Daizo-hoin, Horyuji Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, November 2014.

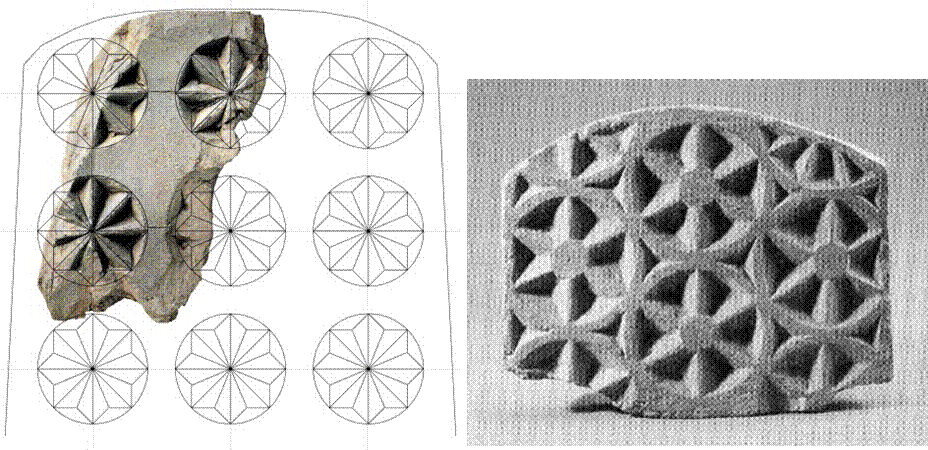

In the literature[22], it was written that “The ridge-end tile of Wakakusa-garan may be related to a similar lotus-flower ridge-end tile found in the relics of extinct Fusozan Temple (扶蘇山寺) of Kudara (百済) Period Korea, [Japan at that time was] no doubt under the influence of Kudara culture.” If the pictures are compared, however, lotus-flowers with eight pedestals are arranged separately on the square lattice in the ridge-end tile of Wakakusa-garan, whereas those with six pedestals were close packed on the hexagonal lattice in the Korean one.

Left: Ridge-end tile from the site of extinct Wakakusa-garan, Horyuji Temple. Duplicated from: Tadahisa Yamamoto, Art of Japan No.391: Onigawara, Shibun-do 1998 (The lines were redrawn by the present writer).

Right: Ridge-end tile form the extinct Fusozan Temple, Kudara. Duplicated from Chida, “A ridge-end tile from Wakakusa-garan, Horyuji Temples, and it relation to Kudara”, Bulletin of National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Nara, 2002

Among the ridge-end tiles with lotus-flower motif were the kinds with only one flower.

![]()

Left: Ridge-end tile with lotus-flower motif, 7th c., from an extinct temple in Yamamura, Ichiyama-machi, Nara. Tokyo National Museum J-35460.

Right: Ridge-end tile with lotus-flower motif, 7th c., from Kume Temple, Okuyama, Asuka, Nara. Tokyo National Museum J-35460.

Both photographed at Tokyo National Museum - Heisei Pavilion by M. Iguchi, November 2017.

A unique rectangular ridge-end tile of Asuka Period (7th century) in which the side view of a lotus flower was designed, unearthed from the temple ruin in Minami-Shiga, Ohtsu, Shiga Prefecture, was displayed in the Tokyo National Museum - Heisei Pavilion. The same type of tile was also shown in the corresponding page of the Ohtsu History Museum’s Website.

![]()

A rectangular ridge-end tile of Asuka Period (7th century) in which the side view of a lotus flower was designed, unearthed from the temple ruin in Minami-Shiga Prefecture. .

Left: Held by Tokyo National Museum (donated by Mr. Kazuo Higo). Photographed at the museum’s Heisei Pavilion by M. Iguchi, November 2017.

Right: Held by Ohtsu History Museum. Duplicated from: http://www.rekihaku.otsu.shiga.jp/news/1705.html.

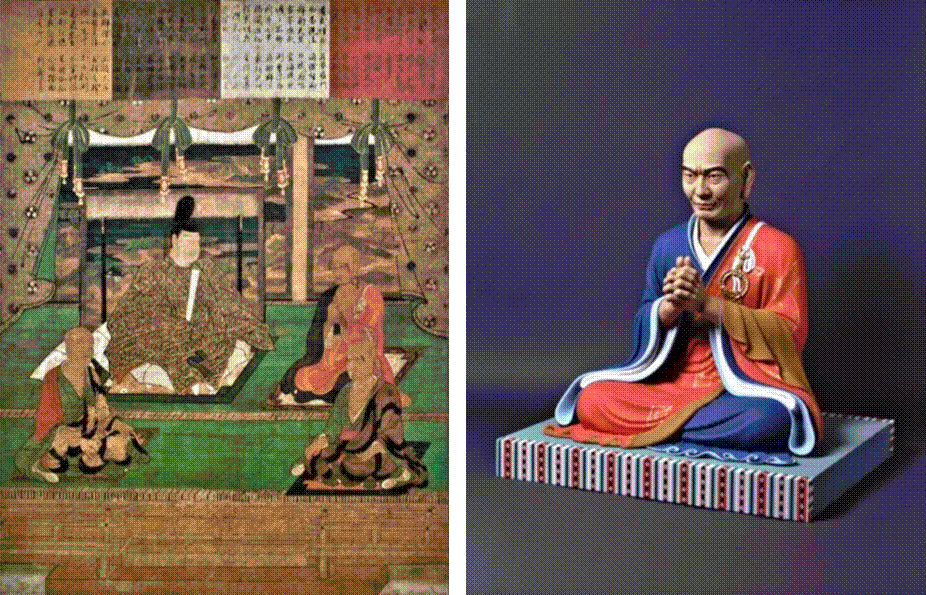

If the ridge-end tile with an ogre face similar to the Kirtimukha originated in Todaiji Temple, why was the reason. A hint for the answer was obtained in The Precious treasures of Todaiji Temple, a rare copy of which I luckily found in the antiquarian book market. Several pages after the “Ridge-end tile of the period of foundation”, I read that Rev. Bodhisena drawn in the “Silk fabric: Four Saints” was the Bodhisena at the ceremony for consecrating the Great Buddha and, confirmed in some other books that he came to Japan from South India in 736 AD. I imagined a scene in that Bodhisena drew a picture of Kirtimukha of his mother country and proposed to adopt it in the ridge-end tile.

Left: Portrait of the four saints. From the left to right: Rev. Ryoben, Emperor Shomu, Rev. Bodhisena, and Rev. Gyoki. Duplicated from: Tobu Museum, The Precious treasures of Todaiji Temple, Asahi Shimbun Publications 1999).

Right: Statue of Bodhisena by Michiyo Miwa 2002. Duplicated from http://michiyo-miwa.jimdo.com/.

Ridge-end tiles of the original Todaiji type have been unearthed in Kinai Area (Nara, Kyoto, Osaka, and Hyogo) but also all over Japan at the sites of Kokubunji Temples (Regional Temples). The piece discovered at the site of Kai Kokubunji Temple that I saw in Yamanashi Prefectural Museum had almond eyes which were not round.

.jpg)

Left: Ridge-end tile from Daianji Temple, mid-8th c.

Middle: Ridge-end tile from West-garan, Horyuji Temple, mid-8th c.

Right: Ridge-end tile from Daigoku-den, Heian Palace., mid-8th c.

All duplicated from: Tadahisa Yamamoto, Art of Japan No.391: Onigawara, Shibun-do 1998.

.jpg)

Left: Ridge-end tile from Kai Kokubunji Temple, 8th c. By courtesy of Yamanashi Prefectural Museum, May 2015.

Middle: Ridge-end tile from Shimotsuke Kokubunji Temple, 8th c. Tokyo National Museum J-35013. Duplicated from: www.tnm.jp.

Right: Ridge-end tile from an extinct temple, Fuchitaka, Ansai, Aichi, 8th c. Tokyo National Museum J-35013. Duplicated from: www.tnm.jp.

In Art of Japan No.391: Onigawara[23] was shown an examples of “Ridge-end tile with ogreish beast motif” of Heijo-kyo period (The former capital in Nara where the imperial palace moved in 710 AD) and stated as though they had preceded the Todaiji one. Nevertheless whether these ridge-end tiles were the original piece may not be immediately concluded, because the capital was burnt and rebuilt several times during its existence of eighty years. Ridge-end tiles with a phoenix pattern and some other variations are also shown.

Left: Ridge-end tile with ogreish beast motif.

Right: Ridge-end tile with Phoenix motif.

Both duplicated from: Tadahisa Yamamoto, Art of Japan No.391: Onigawara, Shibun-do 1998.

While the design of ridge-end tiles metamorphosed, the emergence of the pieces with the face of ogre with horns that persists to date said to have been in the mid-Muromachi Period (15th century). In fact, the ridge-end tiles on the existing Great Buddha Hall of Todaiji Temple rebuilt in the early Yedo Period (17th century) had two short horns and the feature of the face was quite different from the original one. The ridge-end tiles on the Great South Gate of Horyuji Temple had two big horns, as the original gate was burned in 1435. With reference to pictures in literature, they are assumed to be the works of the 15th century. Ridge-end tile tiles on other buildings, save those on Daizo-hoin, were also the kinds with two horns.

Ridge-end tiles of Great South Gate, Horyuji Temple, west side (left) and east side (right). Both photographed by M. Iguchi, November 2014.

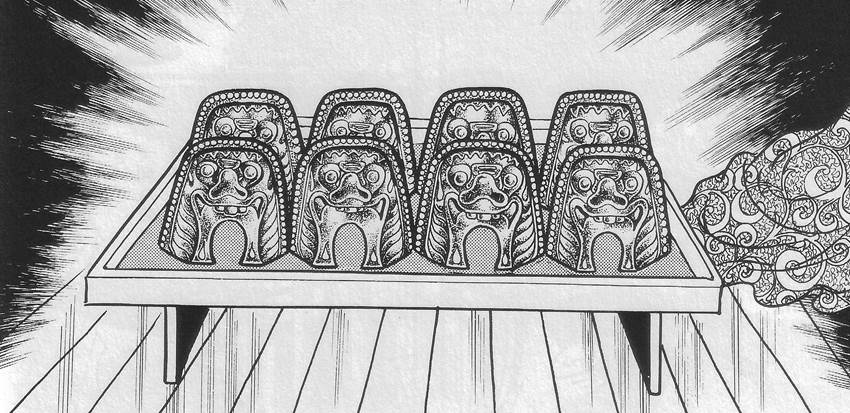

A column in Art of Japan No.391: Onigawara, entitled “A fine work of Osamu Tedzuka: Firebird”, reminded me of a friend who passed away long time ago in his forties. At that time I was swayed by the notion that a story must be read or heard and had a prejudice to comics but, as soon as I obtained a copy of the reproduction edition of Firebird-Phoenix, I was absorbed in the Tedzuka Osamu’s world. In that book, the name of the artist who sculptured the ridge-end tile of Todaiji was Akanemaru, although historical evidence was unknown to me. The design in the comic book was almost the same as that discovered at the site of extinguished auditorium, the image for which Akanemaru obtained by praying to Manjusri.

Ridge-end tile worked by Akanemaru. Partially duplicated from: Osamu Tedzuka, Firebird-Phoenix (Reproduction edition), . Asahi Shimbun Publications 2002.

Having realised that the quality of a comic book depends upon the author, I found and obtained a reprint copy of Tezuka’s Faust (a comic version of von Goethe’s play of the same title, first published in 1950 from Fuji-Shobo) which I had read in my boyhood.

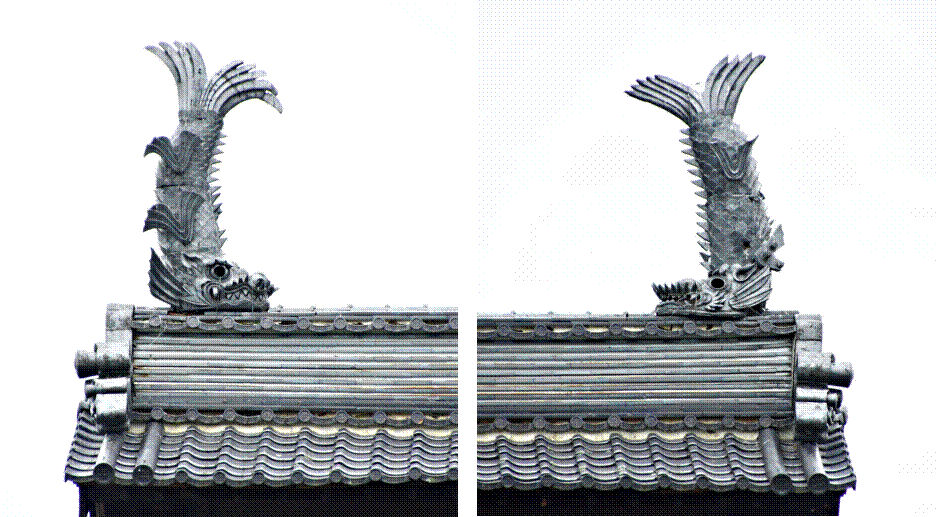

(9) Shibi, Shachi and Makara in Japan

Makaras which I saw in Java reminded me of Shachi-gawaras (鯱瓦, lit. Orca-tiles) which are symbolically placed at the ridge-ends of Japanese castles. I imagined that a Shachi-gawara in which the wish of fire prevention was entrusted must have originated from Makara, the vehicle of the Hindu goddess of water, Ganga Ma, or the god of sea, Varuna.

Shibi

Among ridge-end ornaments of temples introduced during the Asuka Period (592-710 AD) from Tang was Shibi (鴟尾 or 鵄尾, Chinese: Shiwei) which was alternatively called Kutsu-gata from its shoe-like shape. The most famous ones exist in the Golden Hall (main hall) of the Toshodaiji Temple in Nara. An original piece prepared at the time of the temples construction (759 AD) along with a piece worked in the Edo Period were seen until recently on the west and east sides of the ridge, although they both were moved into the New Treasure House, having been designated national treasures. The fact that Shibis had also existed in the older Todaiji Temple has been confirmed from archaeological finds and gold-coloured imitations are now shining on the roof of Great Buddha Hall. The pair of Shibis on the roof of Daigokuden (council hall) of Heijo Palace reconstructed at the site of the ancient capital in April 2010 to commemorate the 1300th anniversary of the capital’s foundation.

Despite its literal meaning as the tail of kite, Shibi is said to have signified the protection form evils and fire, originating from Makara. [24]

.jpg)

Shibis on the Golden Hall of Toshodaiji Temple (Replicas).

Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2015.

The real ones has been moved and stored in the New Treasure House.

.jpg)

Shibis on the Great Buddha Hall of Todaiji Temple (Imitations).

Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2015.

Let us see a picture of a piece of shibi unearthed from the Tosaka Temple (Takaida Ruined Temple), Kashiwara, Osaka Prefecture. The temple is one of the so-called “Kawachi Six Temples” which was recorded to have been visited by Emperor Kouken in February, the 8th year of Tenpyo-Shouhou (756 AD). The shibi measures as large as ca. 135 cm tall and ca. 46 cm x 90 cm at the bottom part and the whole body was covered by gold foil placed on the occasion of restoration. The design of the side face was similar to that of Todaiji and Tosgodaiji Temples and two chrysanthemum flower patterns were seen at the edge surface.

A piece of shibi unearthed from Tosaka Temple (Takaida Ruined Temple), Kashiwara, Osaka Prefecture

Photographed at Tokyo National Museum - Heisei Pavilion by M. Iguchi, November 2015.

Shachis on castles

Let me return to Shachi-shaped ridge-end tiles. The pair of golden Shachis of Nagoya Castle which were famous for the saying, “Owari Nagoya prospers with the castle” were familiar to me since my childhood, as I lived near-bye and saw the castle almost everyday. In a collective volume of essays, Kinofu no Yume (Yesterday’s Dream)[25], the author, Marquis Yoshichika Tokugawa, the 19th Head of the Owari-Tokugawa Family, wrote that although the castle was designed and built by Kiyomasa Kato in the 17th year of Keicho Era (1612), the golden Shachis were installed in a later year by the Family, at the expense of 1940 pieces of Oban-golds (Large-size gold coins) or 17,975 Ryous, a currency unit at that time. Assuming the gold and silver used were 72.119267 kwans (270.117 kg) and 13.44163 kwans (250.406 kg), respectively, the total amount was estimated as ¥961.894 on the basis of the market prices in the 1920s. At the present value, it would be estimated as ¥1,311,987,840 if the prices of gold and silver are assumed to be ¥4,860 and ¥66, respectively.

The apparent amount of stipend of Owari Clan was 619.500 koku of rice but, adding the revenue from the wood from Kiso forests and other resources, the actual revenue was more than 900,000 koku/year. This corresponded to over 900 thousand ryous/year in currency as 1 koku was equivalent to 1 ryou, or to the present-day 90 billion yens, if 1 koku in the early Edo Period was assumed to have been ¥100,000. Thus, the 18 thousand ryous spent for the golden Shachis was not so large for the budget scale of the clan but they were certainly expensive ones compared to those in other castles.

It is written in the Marquis Tokugawa’s book that the original gold plates were replaced with gilt copper plates and further with copper plates with a thinner gilt during the financial difficulty in the 11th year of Kyoho Era (1726 AD) and the 9th year of Bunsei Era (1826), respectively, in order to recover some amounts of gold, but the gilt was made thicker again in the 3rd year of Kouka Era (1846) as the thin gilt came off easily. The amount of gold used at that time was 20.531 kwans (76.99 kg). Kinofu no Yume (Yesterday’s Dream) is now a very rare book but interesting to read.

Besides the information mentioned above, the story that a burglar named Kinsuke Kakiki had reached the top of the castle by means of a large kite and stole two pieces of scales is found in the same section. The whole book including essays on a variety of topics was written in a witty and humorous style, characteristic to the author.

Despite the wish entrusted to protect the castle from fire, the Shachis as well as the whole castle was burnt down by the air raid on the 14th May 1945 during the time of the 2nd World War. It is said that 88 kilogram of gold was used when the present castle was rebuilt in 1959 with steel-reinforced concrete.

It is said that the person who first put Shachis on the edge of castle was Nobunaga Oda and the place was his Adzuchi Castle built in 1579[26], [27]. The piece of Shachi reproduced with reference to fragments discovered during the recent archaeological survey bears gold on the eyes, the upper lip, the fins and the tail. This design looks sophisticated and elegant to my eyes, fitting the high aesthetic sense of Nobunaga, unlike fully golden Shachis invented in later years by the gold-worshipping Hideyoshi Toyotomi and became the standard.

Left: The drawing of the top of keep. Held in Nagoya Castle Management office.

http://www.museum.city.nagoya.jp/exhibition/special/past/tenji080906.html

Right: Reproduced Shachi of Adzuchi Castle. Duplicated from: Masayuki Kido, Tenka-fubu no shiro-Adzuchijo (天下布武の城・安土城), Shinsensha (新泉社) 2004.

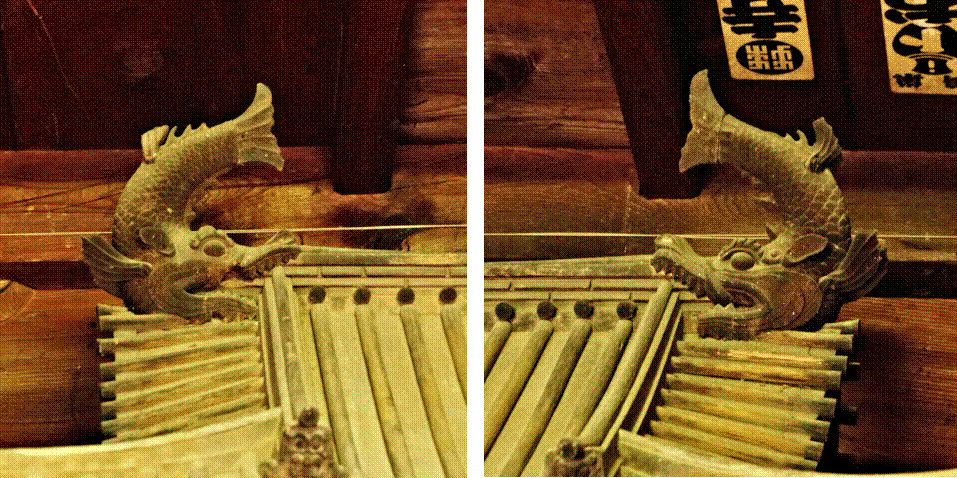

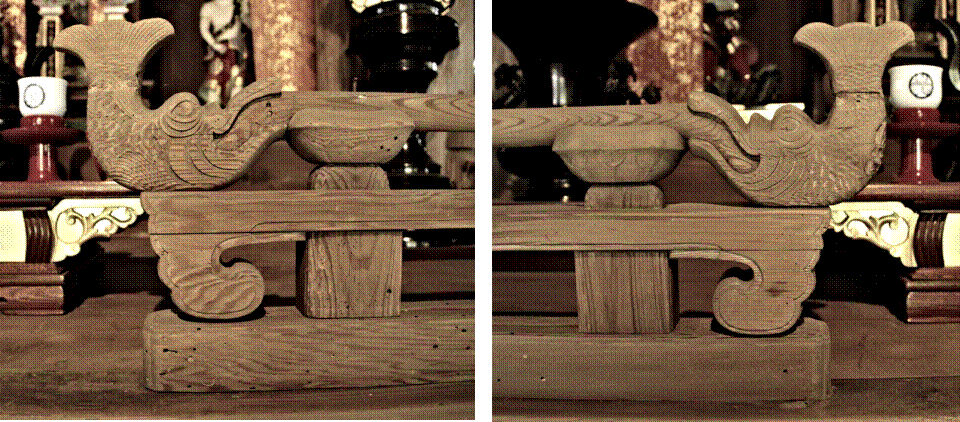

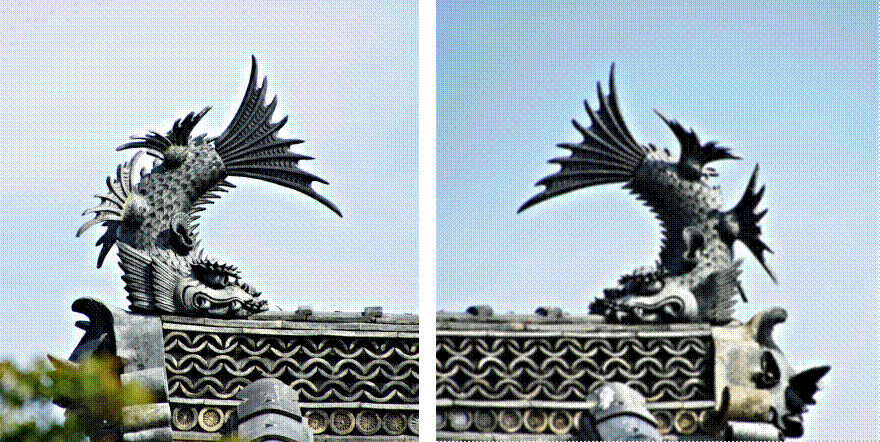

Shachis attached to interior shrines or dais

Shachis are said to have emerged in the Muromachi Period (1336-1573) on the ornament ridge-ends of temples in place of Shibis, . although no buildings of that period with Shachis remain today, however some interior shrines can be found.

Having read that one of the oldest pieces exists in the Kwannon Hall (main hall) of Ichijozan Daihoji Temple, a Zen temple in Aoki Village in Nagano Prefecture, I paid a visit. The temple built in Taiho Era (701-704) was located at the foot of a mountain in the suburbs of Ueda City and the Kwannon Hall and the Three-storeyed Pagoda were found above the stone steps of a slope. I was met and guided by courtesy of the chief priest. The interior shrine situated in the Kwannon Hall, donated in the Nanbokucho Period (1336-1392) by the Hojo Family who ruled this area at that time, was a magnificent one with a hipped roof as high as 9 feet tall, representing the pure Zen-style architecture. According to the chief priest, the pair of wood-carved Shachis placed at the ridge-ends was a pair, the one in the right-hand side with fangs being the male and the other on the left-hand side with no fangs, female. He also told me that a Shachi represents an imaginary sea-fish that functioned as a charm against fire. It must be no other than the Makara of the Hindu myth! The condition of the interior shrine was pretty good and the carvings looked sharp and lively.

Top: The interior shrine of Kwannon-do, Ichijozan Daihoji Temple.

Bottom: Shachis on the left- and right-hand side ridge-ends of the interior shrine.

All pictures were especially taken and presented for this article and belong to Daihoji Temple (September 2014).

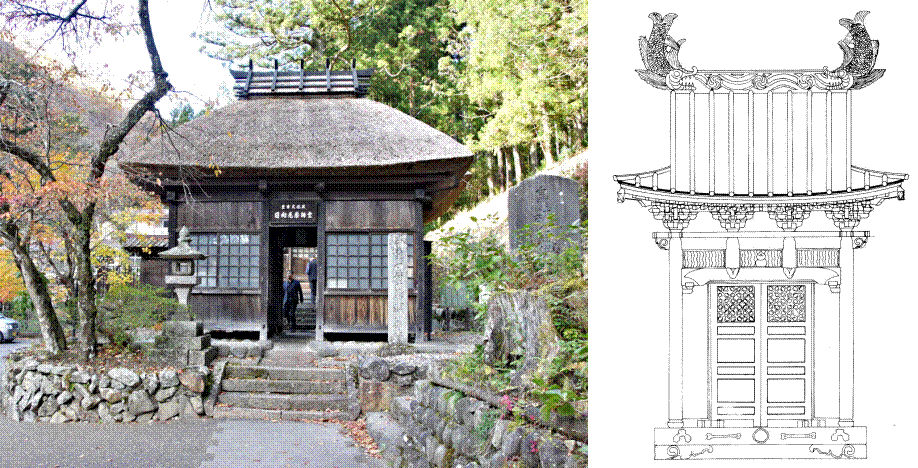

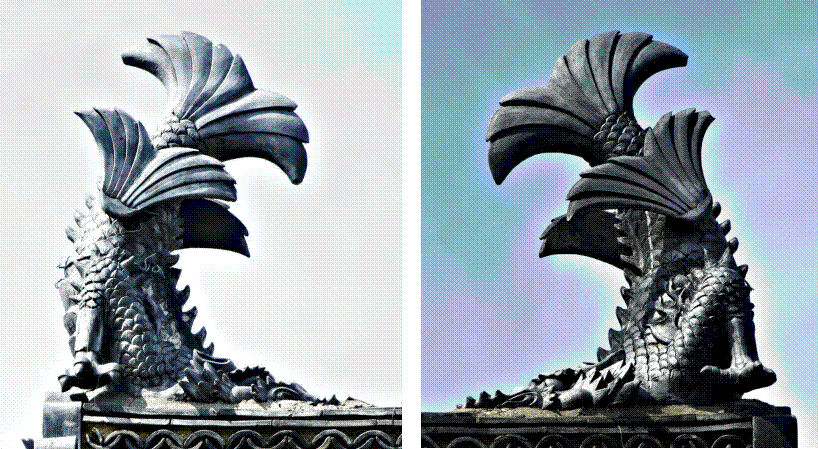

The second temple that I visited to see interior shrine and Shachis was Kashiwawozan-Daizenji Temple, Katsunuma, Yamanashi Prefecture. There again I was kindly received by the chief priest of the temple. According to legends, the temple was founded in the 2nd year of Yoro Period (718 AD) by Rev. Gyoki who saw a vision of Yakushi-nyorai (Bhaisajyaguru or the Buddha who was able to cure all ills) having a bunch of grapes in his one hand on a rock at the nearby Hikawa Valley and dedicated the statue of the guru. The interior shrine in the present Yakushido (main hall), donated in the 1st year of Kenmu Period (1355 AD) by the Takeda Family was a majestic one of about 3.5 metres tall, flanked on both sides by the statues of the Twelve Guardian Deities, Candraprabha and Suryaprabha, all sculptured by Renko, a member of Keiha School. Shachis were seen at the rear-side ridge-ends of a complex pipped roof. Unlike three-dimensional, realistic Shachis in Daihoji Temple, the sculptures looked to have been cut out of a flat wooden board and the contours were simplified and deformed. There seems to be no distinction of sex for these Shachis. The Shachi on the right-hand side lacked the caudal fin, probably lost during the past restoration.

Top: Interior shrine of Kashiwawozan-Daizenji Temple.

Bottom: A pair of Shachis at the ridge-ends.

All pictures were especially taken and presented for this article and belong to Daihoji Temple (October 2014).

With regard to a pair of Niou (Dvarapala) statues and sculpture of lion in the temple’s main gate, I discuss these in the later sections (“3. Dvarapala or Deva King Statues” and “4. Lion Gatekeeper Statues”.)

Daizenji Temple is said to be the place of origin of the Koshu grape and I bought a bottle of wine produced in the temple’s own winery from the temple’s own vineyard.

I have visited one more temple, Hinatami-Yakushido, at Shima, Nakanojo, Gunma Prefecture. Although observing the interior shrine was not possible because the opening of the door was allowed only on the birthday of Gautama (the 4th April), I was able to meet the chief priest and hear about the temple’s history. The main hall which retains the characteristics of Sino-Japanese architectural style is a building built in the 3rd year of Keicho (1598) by the then Lord Nobuyuki Sanada but the interior shrine is said to be older, having been constructed in the 5th year of Tenbun (1537). A booklet[28] presented by the chief priest included a detailed plan of the inner shrine with a pair of Shachis. The dorsal and ventral fins of this Shachis look distinguished compared to the above two examples.

Left: The front view of Hinatami-Yakushido, Photographed by M. Iguchi, October 2015.

Right: The plan of the inner shrine. dupriated from The Collections of Nakanojo Museum of Folk History Museum Vol.2: The History of Hinatami-Yakushido of the Sanada Clan.

Upper part of the plan (magnified view).

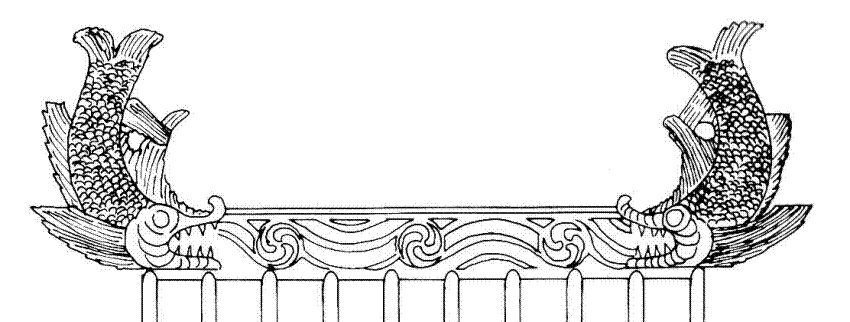

A rare example where a pair of Shachis are attached to the shumidan (dais) for placing an interior shrine on it existed in Oumusan-Jokoji Temple located on a hillside in Seto, in the east suburb of Nagoya. The main hall (commonly called Bujiin), built in 1336 (the 3rd year of Kenmu Era) by a Zen priest, Kakugen (覺源) and renovated in 1534 retained the vestiges of ancient times with the original architectural components and a thatched roof[29]. Shachis found at the balustrade holding the ends of upper handrail in their mouth and sitting on the middle handrail were flat but realistic and the shapes of the left- and right-hand side ones were apparently the same. Judging from the grain, they looked to have been carved together with the handrail from single pieces of wood.

Shachis attached to the handrail of shumidan (dais)

The interior shrine in the main hall of Oumusan-Jokoji Temple, Seto.

Photographed with special permission by M. Iguchi, October 2015.

Shachis on exterior temple buildings

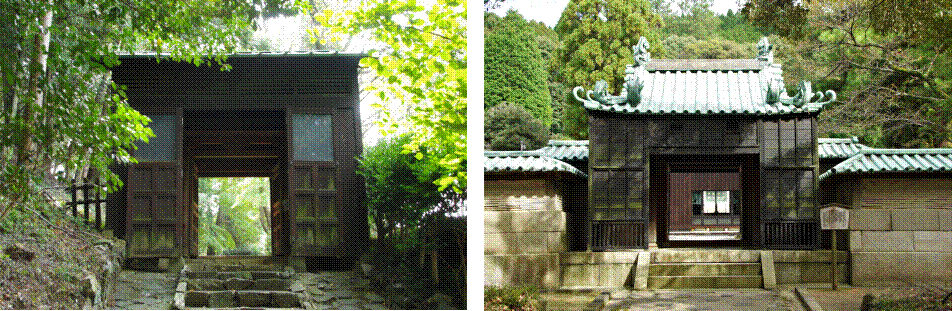

In Jokoji Temple there were exterior buildings with Shachis on their roofs. The family temple of the Owari-Tokugawa, Jokoji had the mausoleum of Genseikou (the posthumous name of Yoshinao, reigned 1603-1650 AD), the earliest ancestor of the family. If one accessed the slope by the main hall and pass the Shishi-mon (lit. Lion Gate) and the Ryu-no-mon (lit. Dragon Gate), the Saimonden or Shokouden (funeral hall or incensing hall) is found in front of the tomb with a Chinese-style gate. The whole facility designed in the Chinese style by Chin Gen-bin, a Zen from Ming who had the audience of Yoshinao and naturalised in Japan, and built in 1652 roofed with bronze and Shachis were found above the roofs of the Ryu-no-mon and the Saimonden as well as the Saikiko (Tool storehouse) located by the side of the later. A question may remain whether the Shachis in this place are not Makaras? I would think they are Shachis because they had no feet that are distinctive of Makaras in general, although no description was found in books and articles.

Leaving aside Chokokuji Temple in Nagano Prefecture rebuilt during the Meiji Era where Shachis were placed on the roof of the main hall (see below), Jokoji Temple is probably the only place where one finds Shachis on exterior temple buildings.

Top Left: Shishi-mon (Lion Gate),

Top right: Ryu-no-mon (Dragon Gate),

Bottom left: Saimonden (Funeral Hall) and Saikiko (Tool Storehouse),

Bottom right: The tomb with a Chinese-style gate.

The Genseikou Mausoleum in Oumusan-Jokoji Temple, Seto.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, October 2015.

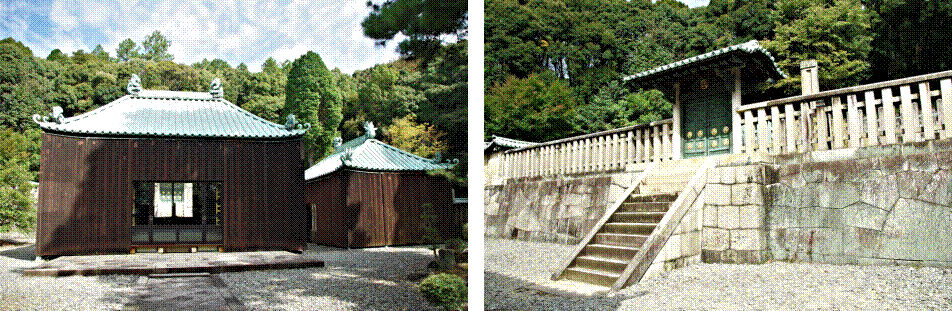

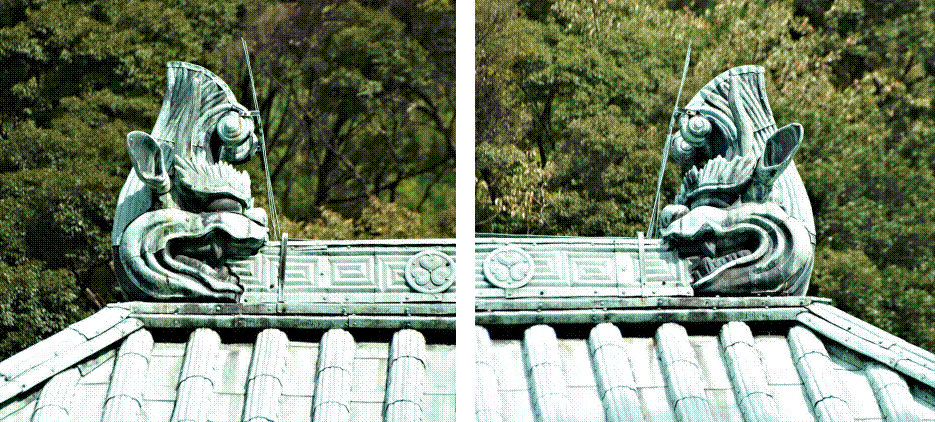

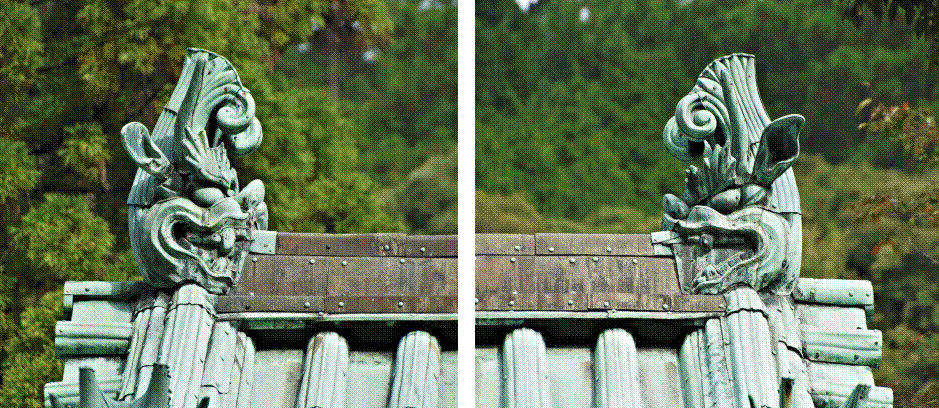

Shachis in Oumusan-Jokoji Temple, Seto.

Top: Ryu-no-mon (Dragon Gate),

Bottom: Saimonden (Funeral Hall).

Photographed by M. Iguchi, October 2015.

The floor of Saimonden (Funeral hall) tiled with the earliest floor tiles in Japan in Oumusan-Jokoji Temple, Seto. Photographed with special permission by M. Iguchi, October 2015.

Although not linked to the guardian of temples, it is noted that the floor of the Saimonden was tiled with ceramic tiles, the production of which Lord Yoshinao had promoted in this pottery district.

Besides the Lord Yoshinao’s mausoleum, the charnel house of the past lords of the Owari-Tokugawa and their wives was built in this temple in 1941 by Marquis Yoshichika, the 19th Head of the Family, as described in “The Last Lord” [30]. So, I asked the vice-chief priest to guide me there and prayed for the soul of Lord Yoshinobu, the 21st Head of the family, who had given me kindness during his lifetime. Behind a stone Buddha from the Northern-Wei Dynasty of China (386-534 AD) placed in the front was a fresco painting depicting he images of Bodhisattvas that I thought was very rare for Buddhist temples but I refrained from taking photograph in the sacred place. Later, I learnt it was a work of Roka Hasegawa, a famous painter for churches[31], and admired to see a part of the tolerant and witty personality of Marquis Yoshichika.

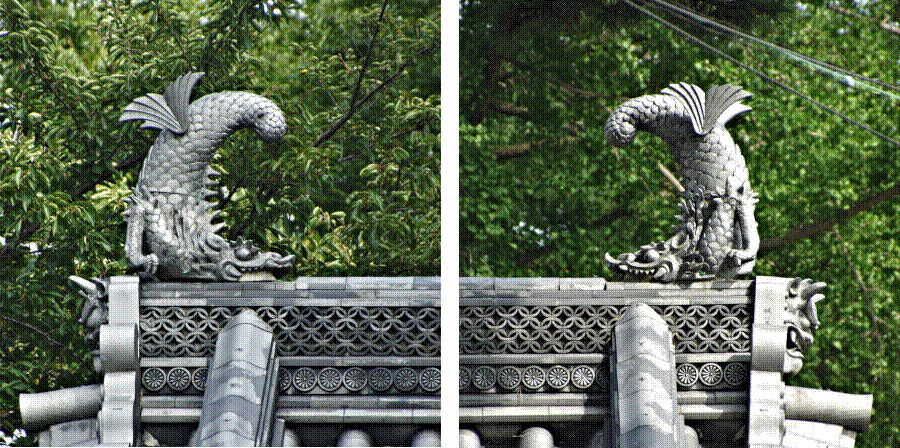

When I visited Nagano Prefecture, I also went to see the Sanadasan Chokokuji Temple in Matsushiro that had a pair of Shachis on the main hall. Despite being located in the middle of the city, the precinct occupied a wide area in a quiet environment. The main hall named Kaizando originally built in 1727 by the Sanada Family was burnt down and the present one was rebuilt in the 5th year of Meiji Era (1872). It was a distinct hipped roof construction with a small upper roof and on the wall underneath of which was a crest of Rokumonsen (lit. Six penny) intrinsic to the Sanada Family. A pair of large Shachis that was as tall as 70 to 80 centimetres were seen on top of the ridge-ends. The Shachis were large because, according to the caretaker of the precinct, they were the ones which used to be on the roof of Kaidzu Castle (commonly called Matsushiro Castle). Compared to typical Shachis of castles, such as of Nagoya Castle, the body of Shachis of Kaidzu Castle looked longer, the part of the body and tail rising upright.

The relocation was an idea of the modern time but looked tasteful befitting to the Zen temple. Close to the eave on the roof were a pair of ornamental objects designed after Karigane (a kind of duck), i.e., another crest of the same family. The Koin, or the quarter of the chief priest’s family, completed in 2005 was a great handsome house with the crests of both Rokumonsen and Karigane on the side of the ridge.

Top: The main hall of Sanadasan Chokokuji Temple, Matsushiro.

Bottom: Shachis on the ridge of the main hall.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2015.

In Horyuji Temple in Nara, I saw Shachis on the roofs of Fumon-in, Seiso-in and Hokko-in but the gates of these buildings used as the residence of priests were closed. I wished to know the history and asked a priest who I met in the precinct but the answer given was just that those buildings would have been constructed in Edo Period, to my disappointment. Somehow, the Shachi did not seem to be beautiful to my eyes, despite their rather complicate design.

Shachis on the ridge of Hokko-in Horyuji Temple, Nara.

Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2015.

When visited Maebashi, Gunma Prefecture, later in November 2019, I saw a pair of Shachis at Soudo-shu Daijusan-Zenoji Temple (usually called Ryukaiin), viz. the ends of ridge of the temple's gate. I read the temple was originally built in 1601 at Okazaki for the Sakai Family and transferred in Bunsei Era (1618-33) to Maebashi with the relocation of the Family by the Tokugawa Government and that the temple's gate as well as the Main hall was the construction of Bunsei Era (1819-33), but the detail of the Shachi was unknown.

The gate of Soudo-shu Daijusan-Zenoji Temple (usually called Ryukaiin) in Maebashi. Photographed by M. Iguchi, Novmber 2019.

Shachis at the ridge-ends of the gate of Soudo-shu Daijusan-Zenoji Temple (usually called Ryukaiin) in Maebashi. Photographed by M. Iguchi, Novmber 2019.

In literature, it is said that the precursor of Shachi was Shifun (鴟吻, Chinese: Shiwen) or Chifun (?吻, Chinese Chiwen) appeared in the mid- and the late-Tang period China and that this ornament had its root in Makara of Hindu mythology.[32], [33] I would imagine that, as far as Nobunaga Oda is concerned, he might have got the idea to put Shachi upon his castle from Namban-jin (Portuguese) who had seen Makara sculptures in India and South-east Asia and with whom he had good company.

The shapes of Shachi seen so far are various. The reason could be ascribed to the fact that the images envisaged by the artists were different as a Shachi in this case was an imaginary creature, not the real creature of the same name (Latin: Orcinus orca).

Makaras