7. Three Pantung Sunda (from Chapter 4)

“Ciung Wanara”, a nickname of the 10th king of the Kendan/Galuh Kingdom (the 8th of Galuh Kamulyan), was probably prefixed to the name of the Garuh remains because it was popular among Sundanese people as a title of Pantun Sunda. The story goes as follows[1]:

“It was when King Sang Permana Kusumah of Galuh was aged and intended to retire from the world that he noticed the desire of Minister Aria Kebonan to be a king. The king called the minister and told him to rule the country but not to harass his two empresses, Pohaci Naganingrum and Dewi Pangrenyep. After his departure to Mt. Padang[2], Aria Kebonan, who somehow resembled the king of ten years younger age, behaved rapacious, declaring the title of Raden Galuh Barma Wijaya.

“In the hermitage on Mt. Padang, an ascetic, Ajar Sukaresi, saw some light from the sky entered the palace and the bodies of the two empresses. Meanwhile, Naganingrum dreamt the stars fell on the moon and Dewi Pangrenyep, a sharp sunlight penetrated the seabed. Barma Wijaya did not believe the dreams and summoned an ascetic from Mt. Padang, but he did not appear soon, just sending some jasmine flowers and turmeric. Barma Wijaya who felt insulted, ordered the empresses to pretend to be pregnant by putting a pot on each stomach. The ascetic, Ajar Sukaresi, who was the former king, Sang Permana Kusumah[3], arrived there and asserted that they were six months pregnant and that both babies would be male. Barma Wijaya was angry and stabbed the ascetic with a keris. The ascetic did not die, as the keris broke into three pieces, but he understood the aim and transformed himself into a snake called Naga Wiru.

“Dewi Pangrenyep first gave birth to Raden Aria Banga. The baby in the womb of Naganingrum voiced and warned the greedy king that the country will soon be destroyed. When Naganingrum delivered the baby, Dewi Pangrenyep who was envious of her fellow concubine swapped the baby with a puppy. The baby was put in a casket with a piece of egg and washed away into Citanduy River, whilst the mother who was sentenced to death was saved by a loyal chamberlain and put in a forest. The casket was found by Aki and Nini Balangantrang in a fish trap installed in the river and the baby was fostered by the couple. After the baby grew to a boy, the boy flew to the air and saw that the heaven and the earth were still separate, a sign that he was entitled to get some inheritance. The child created a village for Aki and Nini.

“One day Aki and the boy went for hunting to the forest with blowguns. When the boy saw a bird and an animal, and asked their names, Aki taught that they are called ‘ciung’ and ‘wanara’, respectively. Then the boy said he must be called Ciung Wanara. From Aki, Ciung Wanara heard of his identity that he was the son of the former king of Galuh and his empress, Naganingrum.

“The egg which had been found along with the baby in the trapped casket turned into a cock, named Si Kakat Beds, when incubated by Naga Wiru. When a cockfight contest was announced from the court, Ciung Wanara wished to challenge Barma Wijaya. The latter who was confident in winning the game with his magical cock, Si Kakat, accepted Ciung Wanara’s challenge, agreeing that the west part of the territory would be submitted to Ciung Wanara, if he was to lose. Si Kakat Beds won the game to obtain the west part of the kingdom for Ciung Wanara. Ciung Wanara was not quite satisfied, as he must be the crown prince of the kingdom. One day he made a beautiful iron cage. When Barma Wijaya and Dewi Pangrenyep came to inspect it and just entered the door to see the inside, Ciung Wanara lost no time to close it. Aria Banga who saw this incident asked Ciung Wanara to free them, but this was not agreed. Then a severe fight began between them and, finally, Aria Banga was hurled by Ciung Wanara to the east of Cipamali River. Thereafter, Ciung Wanara and Aria Banga ruled the western and the eastern parts of Java Island bordered by the river.”

That an iron cage was used in the 8th century might sound unrealistic, but it could be possible to make one by the forge-welding method by employing the tempering technique, which existed since ancient time to make keris and other weapons.

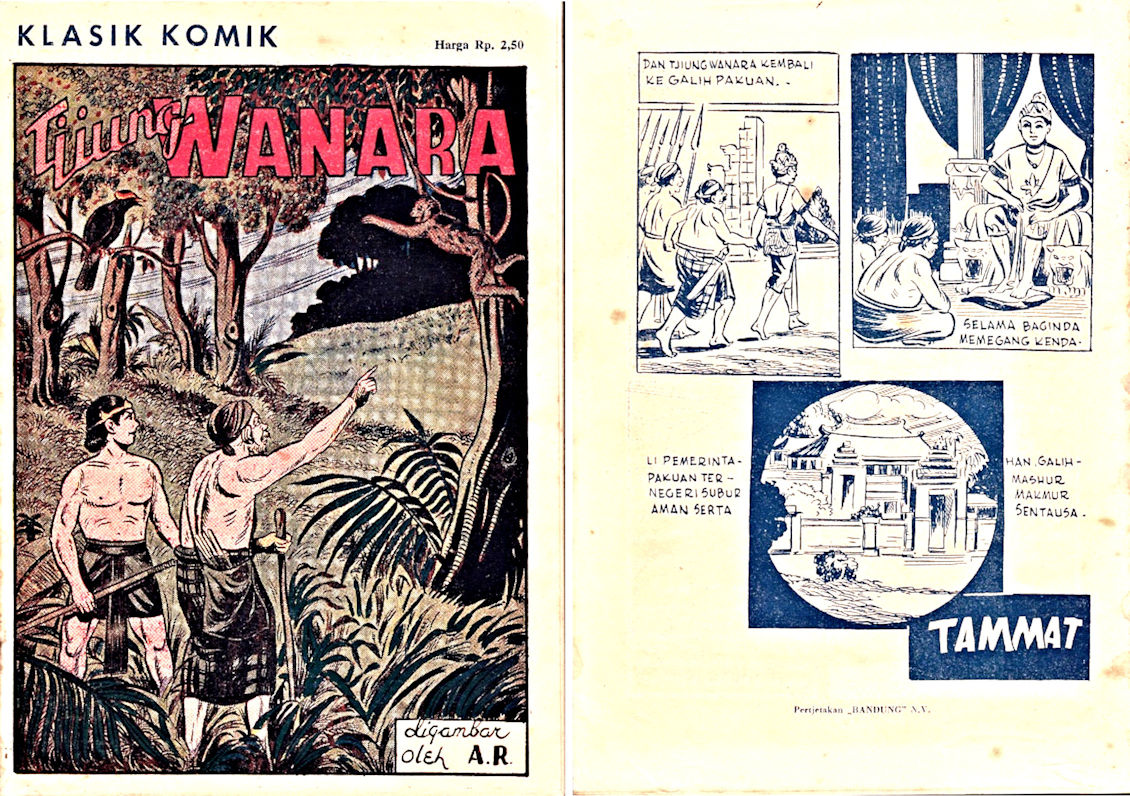

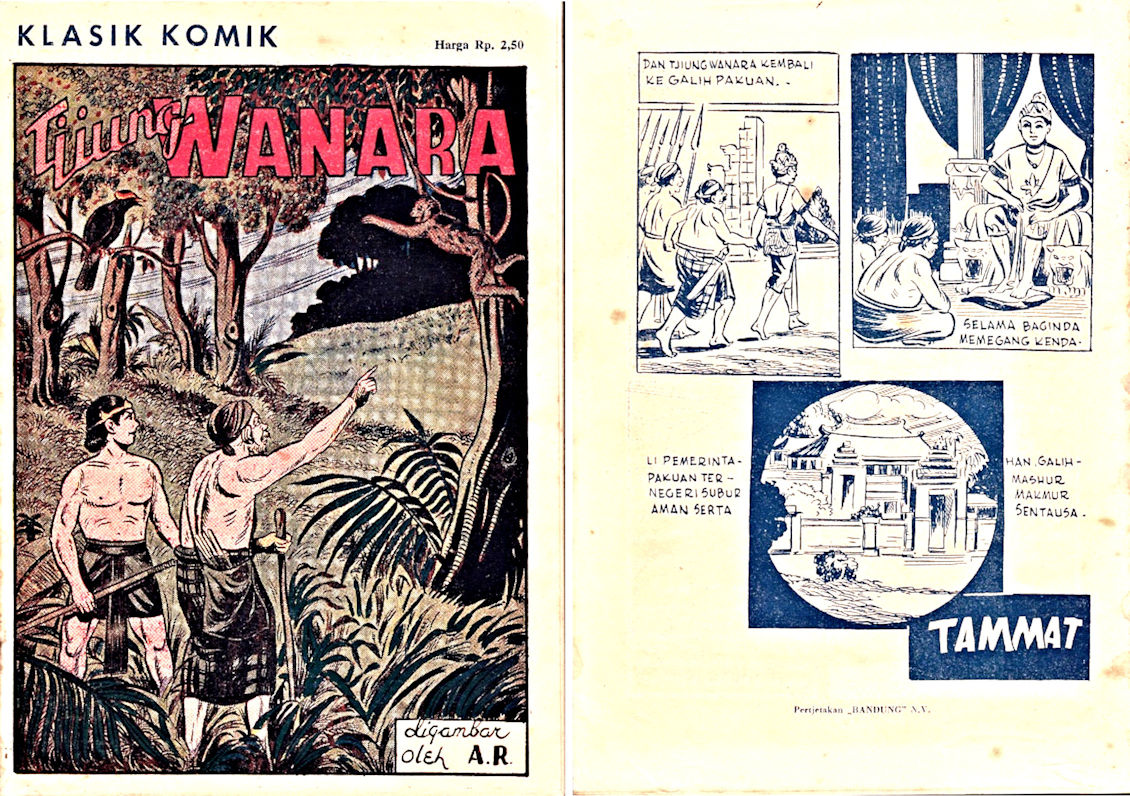

Cover and the last page of an old comic book, Tjiung Wanara, illustrated by Karya A R, Toko Melodie, Bandung 1954. TAMMAT = Happy ever after. Duplicated from: http://patinantique.blogspot.jp/2016/06/komik-legenda-wayang-indonesia.html

Lutung Kasarung, another title of contemporary Pantun Sunda that must be related to Manisuri (or Dharmasakti), the son-in-law of Ciung Wanara, is also famous. One version, which was written in a picture book like a fairytale, is as follows[4]:

“Guru Minda, the son of Dewi Sunan Ambu in Kahyangan [Heaven] was transformed into Lutung Kasarung [Black Monkey] and pushed down to the earth, because he wished to love her mother. He was taken to the palace by a hunter, where Purba Rarang, the elder daughter of Prabu Tana Agung, was monopolising the power by poisoning her younger sister, Purba Sari, to suffer from a skin disease and isolating her in the forest. She did it as she was jealous when the king was about to hand over the throne to the younger sister in accordance with the custom. Lutung Kasarung who was expelled from the palace, disliked by Pruba Rarang, met grief‐stricken Purba Sari in the forest, where Sunan Ambu occasionally appeared and gave her hand. Purba Sari was actually born to Prabu Tana Agung and his queen when they wished to have a beautiful daughter like Dewi Sunan Ambu who had appeared to their bedside. When Purba Sari bathed in a pond created by the tears of Sunan Ambu, her skin was healed and she revived into a beautiful princess.

“Although Purba Rarang gave various difficult problems to the younger sister, Lutung Kasarung solved them one by one. Purba Sari went to the palace. As soon as she heard the voice of heaven and declared that she was the legal successor, Lutung Kasarung took off his coat and turned into a handsome young man. They ruled the country wisely and the kingdom of Galuh prospered.”

The episode that the pond water was effective for the skin disease of Purba Sari could mean that it was hot-spring water from volcanoes existing in the surrounding areas.

Among various long and short versions of Pantun Sunda[5], a story recorded in Stamford Raffles’s The History of Java[6], probably a dictation of a narration, is very specific in that the above two stories were connected. In short, it is written that Lutung Kasarung was the name given by his father, Ciung Wanara, together with a black-monkey coat, and that a son born between Lutung Kasarung and Purba Sari was Silawangi (Siliwangi) who became the king of Pajajaran, which prospered under his reign. Although there was actually a time difference of more than 600 years from the end of Galuh in the middle 9th century to the foundation of Pajajaran in the late 15th century, presumably the narrator would have linked the two historical heroes by his own idea in this fictional tale. One point that is common in both Lutung Kasarung and Siliwangi stories can be that both of them encountered their future partners, Purba Sari and Ambetkasih, respectively, with their identities hidden, being covered by the black-monkey coat or being painted with a black mixture of soot and sap.

The Raffles story furnished some knowledge of contemporary social background. For instance, (1) fishermen installed traps in the river; (2) rice-growing was propagated; (3) a significantly large ship was used to travel along the southern coast of Java Island; and (4) various plays were performed in the feast at Pakuan.

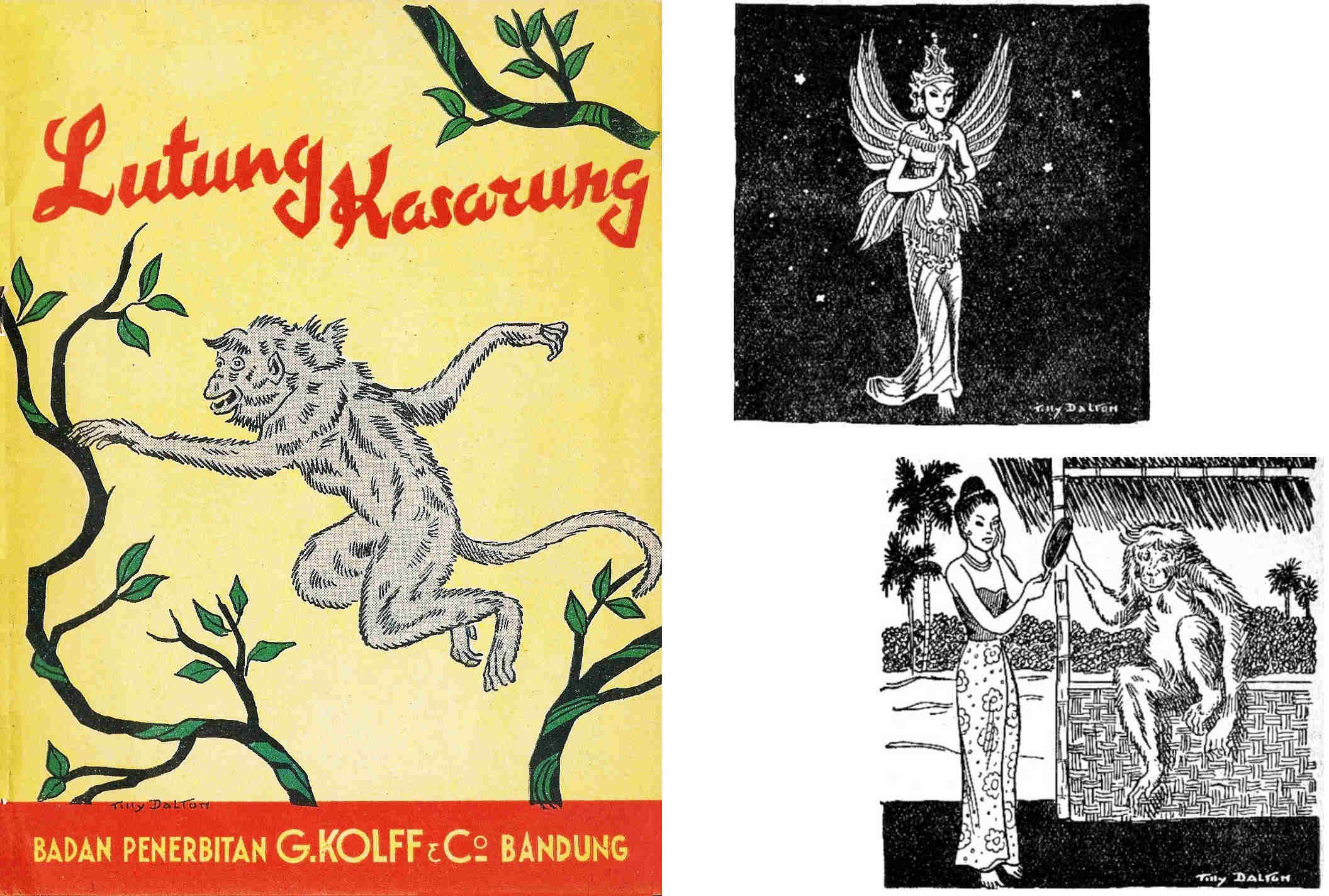

Cover and some illustrations of: Till Dalton (Illust.), Lutung Kasarung, G. Kolff & Co., Bandung (ca. 1950)

(3) The story of Bujangga Manik

Most of Pantun Sunda, including those cited above, were based on episodes of kings and princes during the period from Kendan/Galuh to Pajajaran kingdoms and, despite being written in poetic phrases, they were principally the kind orally told to public audiences. It was natural because the literacy of common people pervaded only after the beginning of the 20th century with the introduction of primary education, but it does not mean that no high-literary poems were written even when the number of readers was limited. A famous example was Bujangga Manik, a long poem of 1,575 octosyllable lines presumably written in the late 15th or the early 16th century. In short, the story was as follows[7]:

“Despite he was a prince of Pakuan, Ameng Layaran (alias Bujangga Manik) became an ascetic monk and travelled around Majapahit in Java, but once returned home sick for his mother. Although his mother urged him to marry Princess Ajung Laran who longed for him, he departed for another journey and reached Bali via Java. Having seen that Bali was highly populated, more than Java, he returned to the territory of Pajajaran and, after roaming around, settled halfway down Mt. Patuha[8] to create a sacred place. He erected a jewelled linga[9], built several pavilions furnished with a kitchen, a shed for firewood and a place for threshing, and completed his practice after nine years. In the tenth year, his body ended without illness, but his soul ascended to beautiful heaven.”

Although the story itself was rather simple, his high mental spirituality was mentioned in many parts of the poem. In addition, a detailed description was given on various scenes throughout the whole volume and the itinerary, particularly of the second trip, was minutely recorded, providing me with useful knowledge of contemporary manners and customs and topography.

In the scene of his visit to her mother after his first journey, for instance, the room where the mother stopped weaving and welcomed Bujangga Manik was situated in a high-floored mansion, decorated with a seven-fold curtain and furnished with a gilded Chinese chest. The cloth she was weaving was an ikat with cotton yarn dyed in red, blue and yellow. From a line of the poem, she was supposed to be an aunt of Siliwangi. When Jompong Laran (probably a relative lady) who had seen Bujangga Manik told Princess Ajung Laran that “he is well-matched for you. He is exceedingly handsome, more than Siliwangi, he is highly intellectual and speaks Javanese, etc.”, the princess presented a tray of betel with her love to Bujangga Manik by entrusting it to Jompong, a tray of betel that she carefully prepared with leaves of sirih (Piper betle), nuts of pinang (Areca catechu), lime stones, fragrant sandalwood, etc., all of the best quality, covered with a ceremonial cloth. The ships that Bujangga Manik took during his trips (from Pamalang, Central Java, to Sunda, and to and from Bali in the first and second journeys, respectively) were large junks[10], the original countries of her crew members having been various, depending on their expertise. On departure, guns were fired seven times, shawms were played, gongs and cymbals were tolled and sailors sung boat-songs.

A question remains about who the composer of this poem was. It would be almost certain that only the traveller himself was able to write, or dictate, the detailed itinerary with the names of mountains, rivers and villages. I should like to conjecture that the whole volume, including the scenes of the death of the hero and the ascension of his soul to the heaven, were composed by a certain prince named Ameng Layaran himself prior to the end of his life.

[1] Yakob Sumarjo, Simbol-simbol artefak budaya Sunda: tafsir-tafsir pantun Sunda, Kelir, Bandung 2003. The details of the story are different in other versions, e.g. Andrew N. Weintraub, “Ngahudang Carita Anu Baheula (To Awaken an Ancient Story): An introduction to the stories of Pantun Sunda”, Southeast Asia Paper No. 34, University of Hawaii 1991. Raden Aria Banga who ruled the area to the east of Cipamari (Brebes River) in this tale is considered to correspond to King Sanjaya, the 5th king of Kamulyan, who moved to Central Java and founded the Sanjaya Kingdom, but the time is reversed.

[2] On the southeast slope of Mount Gede/Mount Pangrango at 885 m from the sea-level is a site called “Situs Gunung Padang”. While the site is considered to have been a sacred place opened in 2000 BC, a local tradition says it was a place connected to Prabu Siliwangi. In “The story of Bujangga Manik”, the hero visited there during his training travel.

[3] In Serat Baron Sakhender, a story after the fall of the Pajajaran Kingdom written in 18th-century Solo was an ascetic, “Ajar Sukarsi” (Chapter 1). Apart from the time difference, the “Ajar Sukaresi” in Mundinglaya Di Kusumah might be the same person.

[4] Till Dalton (Illust), Lutung Kasarung, G. Kolff & Co., Bandung, ca. 1950, etc.

[5] E.g. Christopher Torchia, Indonesian Idioms and Expressions: Colloquial Indonesian at Work, Tuttle 2007; Andrew N. Weintraub, “Ngahudang Carita Anu Baheula (To Awaken an Ancient Story): An introduction to the stories of Pantun Sunda”, Southeast Asia Paper No. 34, University of Hawaii 1991.

[6] T. S. Raffles, The History of Java, Vol. II, London 1817 (Reprint with an introduction by John Bastin, Oxford University Press, Singapore 1988).

[7] J. Noorduyn, A. Teeuw, Three Old Sundanese Poems, KITLV Press 2006.

[8] While a mountain called Gunung Patuha exists 35 km to the southwest of the present-day Bandung, the location of Lingga Payung is unknown.

[9] Virile member, the symbol of Hinduism.

[10] With regards to the junk from Bali, the width and the length were indicated as 8 and 25 fathoms (14.6 m and 45.7 m), respectively.