6. Siliwangi legends (from Chapter 4)

Sri Baduga Maharaja appears in traditional tales as Prabu Siliwangi, the nickname that is more familiar among Sundanese people. Due to the fact that the traditions were the kind that used to be orally narrated in poetic phrases, called Pantun Sunda, and dictated only in the modern age, different versions of short and long length are known today even for one title. Among them, Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi (The Story of King Siliwangi) was a tale in which his early life is told. Let us follow the story in a book, Khazanah Pantun Sunda (Treasure of Pantun Sunda)[1], which, as far as I have encountered, is the most comprehensive one.

“Pamanahrasa born of Prabu Anggalarang and Queen Umadewi of Pajajaran grew up to be an elegant and smart boy. When he was nine years of age, Parbamenak, his fifteen-year-old half-brother from one of the king's concubines, had conspired to murder him from envy of Pamanahrasa’s legal right of succession. He invited Pamanahrasa to Sipatahunan River, lying that he would help Pamanahrasa with testing the latter’s ability to be the future king. The first task was to cross the river that three white crocodiles inhabited, but Pamanahrasa was able to safely reach the opposite side, as the three savage animals somehow fought and killed each other. The second task was to climb up the Sanghiang Kekeumbingan by hauling a vine by arm power. When it was achieved, Parbamenak blamed Pamanahrasa that it was a serious sin to have set foot on top of the peak, which was a sacred worship place. Having been sentenced to be a slave, the whole body of Pamanahrasa was painted black with a compound of soot and sap and his name was changed to Siliwangi, to conceal his identity, before he was sold at a port to a nakoda [captain].

“In Sindangkasih [near the present-day Purwakarta], Dewi Ambetkasih, the daughter of Ki Gedhe Sindangkasih [the first younger brother of Prabu Wangi of Sumedanglarang], had a dream one night in which a black, ugly slave appeared, accompanied by a young man, and said to Ambetkasih that he would serve her as her younger brother, if she would buy him. While she hoped the dream would come true, one day her maid brought news that a nakoda from Palembang named Minadi was wishing to sell his slave to pay for repairing his damaged boat. Ambetkasih had lost no time to speak to her parents and took the black slaves in her custody in exchange for some teak wood and a small junk. After then, there was an incident that the garden of Ki Gedhe’s palace was often damaged. Siliwangi was suspected and created a problem for Ambetkasih.

“Meanwhile, three chamberlains of Siliwangi, i.e. Parwakalih, Gelap Nyawang and Kidang Pananjung, who had been in search of their master for five years, received an instruction from a hermit at Meru Kidul and came down towards Riwahan and reached Kampung Kategan to stay in disguise at Kuwu Kawanda’s house. The village became prosperous thanks to the farming skill of the guests. One day when Kuwu delivered fruits and vegetables to Ki Gedhe, his wife was much delighted with the quality of the crops and invited the three visitors to let them repair the damaged palace garden. They instantaneously recognised that the black slave they saw was their master, but kept it secret at that moment. Next day, when Ki Gedhe, his wife and the daughter went to see the restored garden, Siliwangi was also there. To Ambetkasih, who worried whether the garden would not be damaged again, the visitors told her to shower water on the slave’s body, as a boy with a skin disease was usually afraid of being made wet. No sooner water was poured than the ugly boy turned into a handsome young man to the surprise of the watchers. Ambetkasih gladly hugged Siliwangi and asked him to become her younger brother. At first, Siliwangi was hesitant, but eventually agreed, having been urged by Ki Gedhe. When the couple were dressed and decorated in royal costume, they looked like Kamajaya and Rati [the Hindu God and Goddess of Love].”

Above is the first half of the story. The last line apparently depicted the scene of their wedding, as it was mentioned in another Siliwangi tale, Ceritera Prabu Anggalarang (The story of Prabu Anggalarang), that the couple did marry and became the king and queen of Sumedanglarang and then of Pakuan[2].

The second half of the story begins with the scene in Singapura[3] where Prabu Singapura was upset as her beautiful daughter, Ratuna Larangtapa, received marriage proposals from kings of eighteen countries and asked the advice of Ki Gedhe Sindangkasih, his second eldest brother. Then, Ambetkasih was despatched to Singapura on behalf of Ki Gedhe, accompanied by Siliwangi, to solve the problem. Leaving aside the details, which are rather complicated and verbose, Siliwangi, who had proposed to select the bridegroom by a cockfight and intended to be the referee, was inevitably entangled in the game and eventually obtained Princess Larangtapa by beating rivals. Many other princesses who gathered there and were admiring Siliwangi unanimously became his concubines.

Although Sri Baduga was no doubt the model of Siliwangi, the setting of the scene and the origins of characters are significantly modified in Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi. For instance, (1) in the tale, a kingdom called Pajajaran had already existed and Siliwangi (Panamahrasa) was born there as a prince, whereas the real Pajajaran Kingdom was founded in a later time by Sri Baduga himself; (2) Pajajaran Kingdom was implicitly written as if it had existed within the territory of Sumedanglarang, with no indication of its capital’s location; (3) the name of the father of Siliwangi in the tale, Prabu Anggalarang, was the alternative name of the 5th king of Kawali, Wastu Kencana, in the chronicle; (4) Prabu Wangi, the name of the king of Sumedanglarang is generally the honorific name of Maharaja Linggabuwana, the 3rd king of Kawali, who was killed in Majapahit[4], etc.

In Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi, it is also noteworthy that Princess Subanglarang, the daughter of Patih Mangkbumi, or the youngest brother of Prabu Wangi, who became the second queen of Sri Baduga appeared just as a minor character, and that Princess Kentring Manik Mayang, the daughter of Prabu Susuktunggal of Sunda Kingdom, whose future marriage with Siliwangi as the third queen was to realise the unification of Kawali and Sunda Kingdoms to found Pajajaran, was not included at all.

This story was allegedly written in Sumedang around the turn of the century from the 17th to the 18th when the Pajajaran Kingdom with its capital at Pakuan had already ceased to exist, and Banten in the coastal area on the west part of the Java Sea, the Kingdom of Mataram arisen in Central Java and VOC (the United Dutch East Indies Company) at Batavia were struggling for supremacy. Although Sumedanglarang had managed to maintain its existence, its status as a country was in jeopardy. It was commented by the author of Khazanah pantun Sunda that, in such circumstances, the court of Sumedanglarang would have preferred to imagine Sumedang as the centre of the glorious Pajajaran Kingdom.

The moving of Ambetkasih to Pakuan from the old capital together with her fellow consorts of Siliwangi is written in Carita Ratu Pakuan[5], in which the procession of palanquins, decorated with gold and jewellery and topped with an ivory ball, started at the shining palace of the east, being led and followed by bands, chorusing, “Let's go to Pakuan!”, as if the procession were waving in the air like a dragon.

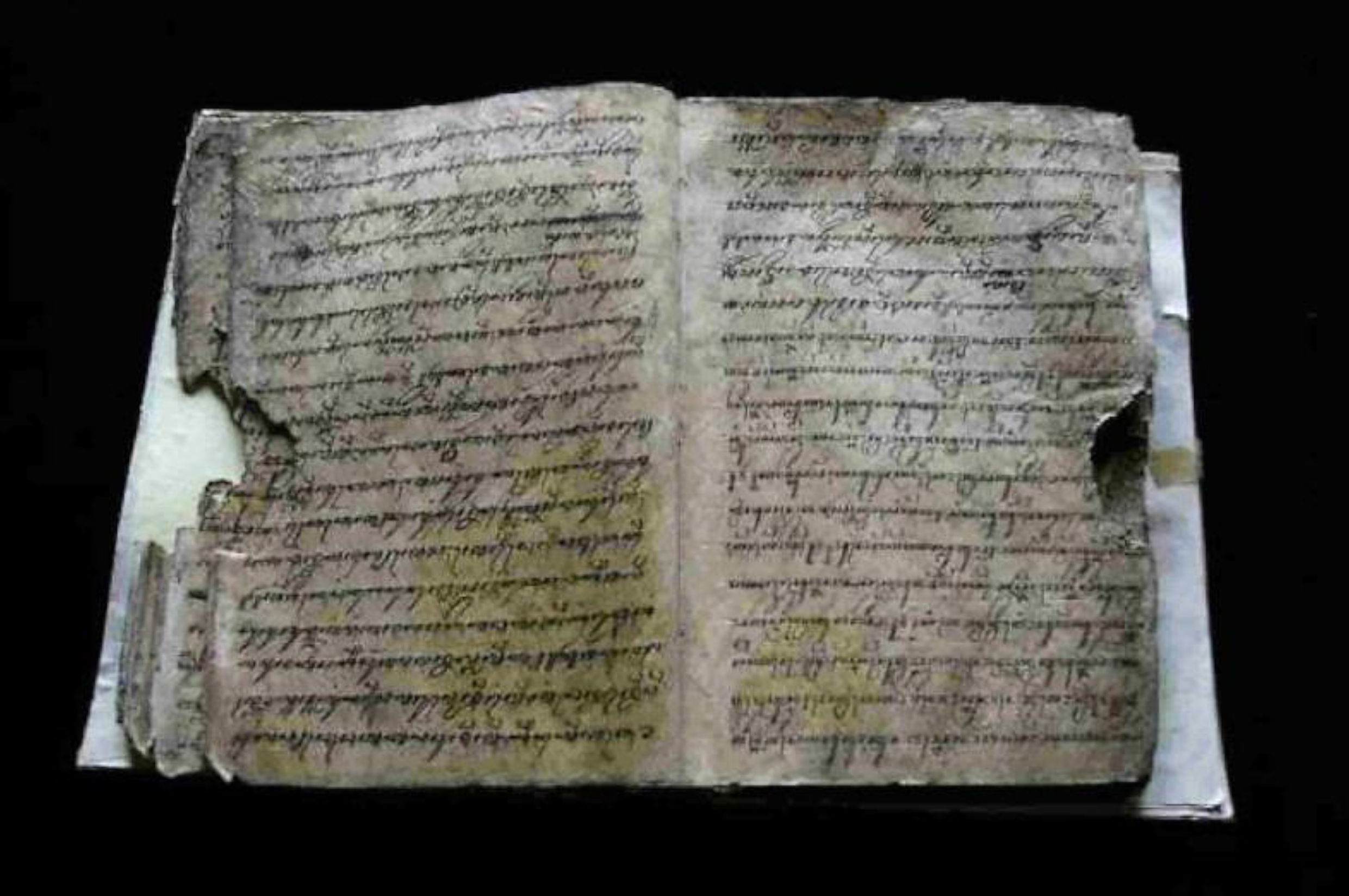

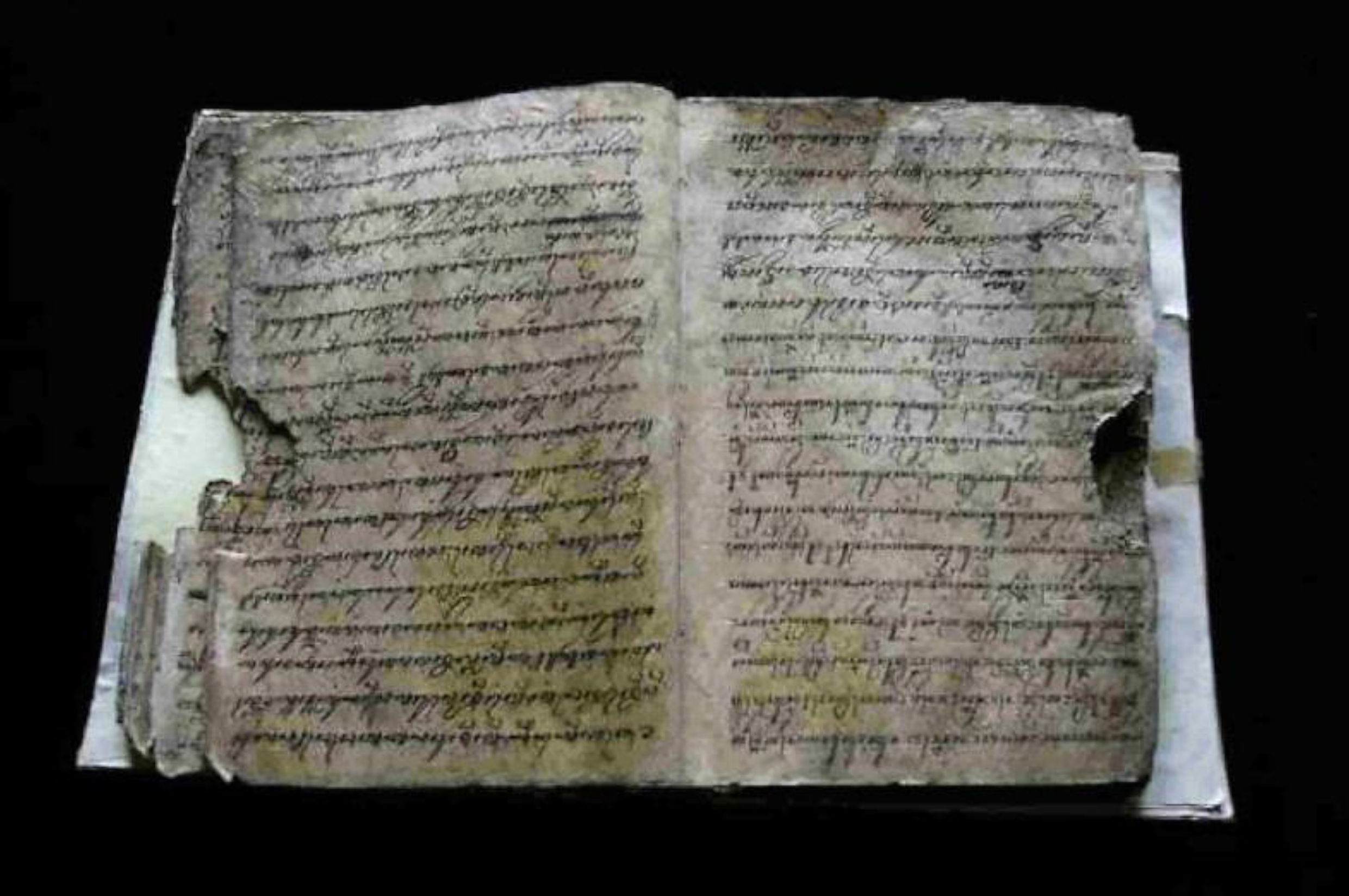

A book of “Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi (Story of Prabu Siliwangi)”, written on daluang, or bark paper (1675).

A belonging of Pangeran Panembahan (1656-1706). A collection of Museum Prabu Geusan Ulun, Sumedang.. Reproduced from the brochure of the museum, Profil Museum Prabu Geusan Ulun.

(2) The Story of Mundinglaya Di Kusumah

An episode of Siliwangi after his coronation was told in Mundinglaya Di Kusumah. One of many versions is narrated[6] as follows:

“The story begins with the scene in which one of the two queens of Prabu Siliwangi of Pajajaran, Padmawati, wished to eat a sour fruit, honje, when she was expecting a baby. Since no ripened honje was found in the country, a confidant of the king went around forests and reached Muara Beres where the confidant of the latter country was picking up the same fruit. The request of the former to hand them over was rejected, because the queen of Muara Beres, Gambir Wangi, was also pregnant. After quarrelling for a while, they realised that the two kingdoms had descended from a common origin and agreed to equally share the eight pieces of the fruits in such a condition that if the two expected babies were of different sex, they should be engaged. After the full term, Padmawati of Pajajaran gave birth to a boy, named Mundinglaya Di Kusumah, and Gambir Wangi of Muara Beres, a girl, named Dewi Asri.

“It was when Mundinglaya Di Kusumah grew up to be a handsome and smart young man that he was insistently slandered, as if he had misbehaved with a young court lady, by another queen of Siliwangi, Nyi Raden Mantri, whose son, Guru Gantangan, was much older and was already the governor of Kutabarang district. Without much investigation, Mundinglaya was jailed. This caused some turmoil in the kingdom.

“One night, Padmawati saw in a dream a beautiful kite with twenty-five golden tails that was brought almost within her reach by some invisible being. When the king summoned scholars and elders and told of his wife’s dream, a famous astrologer explained that the kite was called Salaka Domas which symbolised welfare and happiness, and that a person who obtained it would ensure the prosperity of the kingdom with eternal life. He added that the kite existing in the heaven was guarded by seven heavenly beings called Guriang Tujuh. The king called his one hundred and fifty sons, but nobody was willing to go on the dangerous journey to get the kite. Then, Padmawati remembered her son in the gaol. When her thought was delivered to Mundinglaya by two chamberlains, Gelap Nyawang and Kidang Pananjung, who both had long served him, he who had enhanced his mental culture even while in prison said that he was very eager to undertake the mission. When he was released for his expedition, Prabu Siliwangi gave him a keris called Tulang Tonggong, a treasure sword of Pajajaran.

“Mundinglaya departed for the heaven accompanied by the two chamberlains. First, they went by boat to the north to Pulau Puteri, a small island in Java Sea, to worm the secret route to the heaven and to obtain magical power from Jonggrang Kalapetong, a giant who lived there, and finally attained the aim by beating the giant. Mundinglaya Di Kusumah flew to the sky and, as expected, encountered Guriang Tujuh. When he was strangled to death and became free from both mental and physical restraints, Goddess Wiru Mananggay, the late grandmother of Mundinglaya, descended and breathed life into the body to revive him as a perfect man qualified to hold Salaka Domas. He returned to the earth, accompanied by Guriang Tujuh who had become his retainers.

“In Muara Beres, his fiancée, Dewi Asri, was in danger, being proposed marriage by Sunten Jaya, the step-son of Guru Gantangan, but Mundinglaya was able to rescue her with the help of Jonggrang Kalapetong whom he had subdued before. In Pajajaran, Mundinglaya Di Kusumah produced Salaka Domas to Prabu Siliwangi and married Dewi Asri. Thus, peace was restored in Pajajaran.”

The details of the story are significantly different between versions. As to the reason of Mundinglaya’s imprisonment, it is told, for instance, in one version, that “While Guru Gantangan and his wife, Nyai Mas Ratna Inten, were fostering Mundinglaya by request, the wife was so much absorbed in Mundinglaya Di Kusumah and forgot about her husband that the husband became angry”[7], and in another version that “Sunten Jaya, the step-son of Guru Gantangan and Nyai Mas Ratna, became envious of Mundinglaya Di Kusumah as his step-parents doted on the latter”[8], and so on. Mundinglaya Di Kusumah is considered to have been modelled after Surawisesa, the 2nd king of Pajajaran[9]. The fact that such an episode was written in Pantun Sunda suggests that some dispute about the succession of throne existed in the court even after the inauguration of Siliwangi, or Sri Baduga Maharaja.

The last two scenes of Mundinglaya Dikusumah Story from Calendar 2011 of PT Pulau Mas Texindo, Bandung. The calendar was formerly uploaded in the company’s homepage but the page is no longer accessible.

(3) A Tale of Tigers in Sancang Forest

The influence of Islam extended to West Java already during the reign of Sri Baduga Maharaja. The description in Carita Parahiyangan that “as long as the teaching of our ancestor is upheld, no enemies, neither soldiers nor mental illness, will come. Happy prosperity prevails in the north, the west and the east. Those who do not feel the prosperity of household are greedy people who learn [foreign] religion” suggests that many populations in the kingdom’s territory were already inclined to Islam. The second queen of Sri Baduga Maharaja, Nyai Subanglarang was, in fact, a Moslem who attended an Islamic school in Karawan[10]. Although one of her sons, Walangsungsang, who became the sultan of Cirebon still had respected his father, his son, Syarif Hidayat, declared independence from Pajajaran by allying with Demak in 1482. Angered by this, Sri Baduga attacked Cirebon but was stopped by the Cirebon–Demak allied army. Although Pajajaran had one thousand men and forty war-elephants, they had only six 150-ton class junks in the sea, which were not compatible with the strong navy despatched from Demak.[11]

With respect to the relation between the king of Pajajaran and Moslems, there is a tradition which tells[12]:

“The kingdom of Pajajaran was ruled by its glorious king, Prabu Siliwangi. Prabu Siliwangi had a son named Kian Santang, a man with great mystical powers. One day, Kian Santang walked on the water to Mecca and was converted to Islam. He returned to Java, assuming the name of Wali Sunan Rahmat. There he attempted to convert Prabu Siliwangi to Islam, but the latter and some of his courtiers rejected the new religion. A confrontation ensued and the king and his court fled into the Sancang forest on the south coast of Java Island, having been pursued by Kian Santang. To avoid a battle with his son, Prabu Siliwangi disappeared and turned himself into a white tiger while all his followers became Sancang tigers. They spread all over the forest and are today considered as an omen of good luck by local fishermen. In his tigrine form Prabu Siliwangi, who is said to still inhabit the area of his old court at Pakuan near Bogor, continues to watch over his descendants and the Sundanese generally.”[13]

In this connection, the famous Siliwangi Division of the Indonesian Army has been named after Prabu Siliwangi and in front of their garrison in Bandung is placed a statue of a white tiger as their symbol. The emblem of Persib Bandung (lit. Bandung United), a strong football team in Indonesia, has a head of a tiger and their home ground is called Lapangan Siliwangi (Siliwangi Field).

In 1687, one half-century later after the fall of Pakuan, an expedition team of VOC headed by Pieter Scipio van Ostende went south from Batavia and passed a place that was supposed to have been Pakuan, the old capital of Pajajaran, in the ravine to the west of Mt. Salak and to the east of Mt. Gede, before they reached the bay of Muara Ratu on the southern coast of Java Island for the first time as foreigners. Van Ostende reported that “the road from Parung Angsana to Cipaku[14] was wide and macadamised, and durian trees were lined on the both sides. At the end of the road was a moat, and beyond the moat was a gate. In the front was a ruined stone masonry, but expedition members were not allowed to go inside the palace, because they were non-Moslems. The area was guarded by tigers. Inhabitants were sparse around there. They still respected the former king, Prabu Siliwangi, etc.” This record indicates that the former capital with an estimated fifty-thousand population was in the state of a ghost town, one century after the fall of the kingdom. It is interesting if tigers were tamed as watchdogs, but it is written in Prof. Danasasmita's book that the tigers were probably wild ones that dwelled there[15]. Otherwise, were they the transformations of Siliwangi and his followers as told in the legend?

Prabu Siliwangi Mural Concept.

Reproduced by courtesy of the painter, Mr. Jaka Prawira, Indonesia, from : http://www.deviantart.com/art/Prabu-Siliwangi-Mural-Concept-401039516

[1] Yakob Sumarjo, Khazanah pantun Sunda, Kelir, Bandung 2006. The author noted that the source was a copy possessed by Raden Demang Cakradijayah who died in 1853, but older copies must have existed. In fact, the copy I saw in Sumedang was a copy of 1675 (See the description in the later part of this chapter). The full text of Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi was found later in Agus Setia Permana, “Balangantrang: Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi”, http://balangantrang.blogspot.jp/2010/05/cariosan-prabu-siliwangi.html.

[2] Moh. Amir Sutaarga, Prabu Siliwangi: Atau Ratu Purana Prebu Guru Dewataprana Sri Baduga Maharaja Taru Haji di Pakwan Pajajaran, Pustaka Jaya, Jakarta 1965. In the real history, the couple was firstly crowned at Kawali and secondly at Pakuan.

[3] The name of a place to the northeast of Cirebon, not Singapore Island off the tip of Malay Peninsula.

[4] “Wangi” literally means “flavour”. “Siliwangi” is said to mean the successor of the great king, Prabu Wangi. About the death of Prabu Wangi (Prabu Linggabuana) in a battle in Bubat, East Java, see a later part of this chapter.

[5] Carita Ratu Pakuan “Naskah Carita Ratu Pakuan (Kropak 410)” http://babadsunda.blogspot.com/2010/07/naskah-carita-ratu-pakuan-kropak-410.html. The book is said to have been written in the late 17th or the early 18th century by a poet, Kai Raga, in Gunung Srimanganti, the present-day Garut county. Although there is a view that this is a sequel of Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi (Ann Kumar, John H. McGlynn, Illuminations: The Writing Traditions of Indonesia, Weatherhill 1996), it may not necessarily be true because the place of the old capital is different. The old capital is considered to have been Kawali (in the present writer’s understanding), although it is noted as Galuh in Saleh Danasasmita’s book (Footnote 6.).

[6] Ajip Rosidi, Mundinglaya di Kusumah, Penerbit Nuansa, Bandung 1956/Yakob Sumarjo, Simbol-Simbol Artefak Budaya Sunda: Tafsir-Tafsir Pantun Sunda, Kelir, Bandung 2003.

[7] Andrew N. Weintraub, “Ngahudang Carita Anu Baheula (To awaken an ancient story): An introduction to the stories of Pantun Sunda”, Southeast Asia Paper No. 34, University of Hawaii at Manoa 1991.

[8] Amanda Clara, Cerita Rakyat Dari Sabang Sampai Merauke, Pustaka Widyatama 2008.

[9] According to the chronicle, the mother of Surawisesa was Kentring Manik Mayang. Note that Ambetkasih bore no legitimate child; Sumbanglarang had three children.

[10] In Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi (1) Subanglarang was the daughter of Minister Mangkbumi and Ki Gedheng Tapa was her brother, and (2) the girl whom Siliwangi obtained after a competition was Larangtapa, daughter of Prabu Singapura.

[11] Saleh Danasasmita (Footnote 6).

[12] Robert Wessing, “A change in the forest: myth and history in West Java”, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 1 March 1993. The origin of the story is not shown in the book but supposed to have been Wawacan Prabu Kean Santang (The Song of King Kean Santang).

[13] Kian Santang was a daughter of Nyai Subanglarang and Walangsungsang was her brother.

[14] Parung Angsana is the present-day Tanah Baru in the northern suburb of Bogor. Cipaku exists in the same name in Bogor city. According to Winker, the width of the road and the distance was three metres and 2.5 kilometres, respectively. The distance matches with the present map.

[15] Saleh Danasasmita (Footnote 6).