Wayang, Javanese Shadow Play and its Derivatives [Part 1 and 2]

By Masatoshi Iguchi

Translation of an article contributed as <Series of Cultural Tradition Associated with Festivals 15>, in Sen’ i Gakkaishi (Journal of The Society of Fiber Science and Technology, Japan , Vol. 72, No.10, p. 483-486; No. 11, p. 523-526, 2016

[Part 1]

1. The first encounter

Elderly readers (in Japan) may remember the shadow play which they played in their childhood by simulating the shapes of dog, fox, et cetera by hands and fingers, casting their shadow on the shoji or sliding paper partition, which separated the living room and corridor, and viewing the shadow from the corridor. Shadow play was popular in Japan from old days as found in a book, Otsuriki (於都里伎), written by Ikku Jippensha and illustrated by Tsukimaro Kitagawa (1810). It' s shadow play but more than that. Although a kind of theatrical performance of shadow play seems to have existed in China, Java is probably the only country where shadow play has been played as an event of festivals for many centuries. Thus, Javanese wayang was registered in the UNESCO’s List of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2003.

It was three decades ago that I had the first opportunity to see wayang. In the Sonobudoyo Museum Theatre near the Sultan’s Palace of Yogyakarta, short versions of the shadow play, locally called Wayang kulit, were performed every night for tourists. Inside the entrance of the traditional pondopo-style building with a double roof was a big hall of some fifteen metres square, in the middle of which was a partition with a screen of white cloth measuring five metres wide and one and a half metres high. On both right- and left-hand sides of the screen were numerous puppets, as many as several dozen, leant against the lower part of the partition wall. The puppets were, as “kulit” meant leather, flat objects cut out from a sheet of buffalo leather and coloured by paints and the shapes of characters were significantly deformed. There was a rod handle in the centre of each puppet, and the upper and lower parts of arms were jointed at the shoulder and the elbow so as to be moveable by means of a narrow rod attached at the tip of each hand.

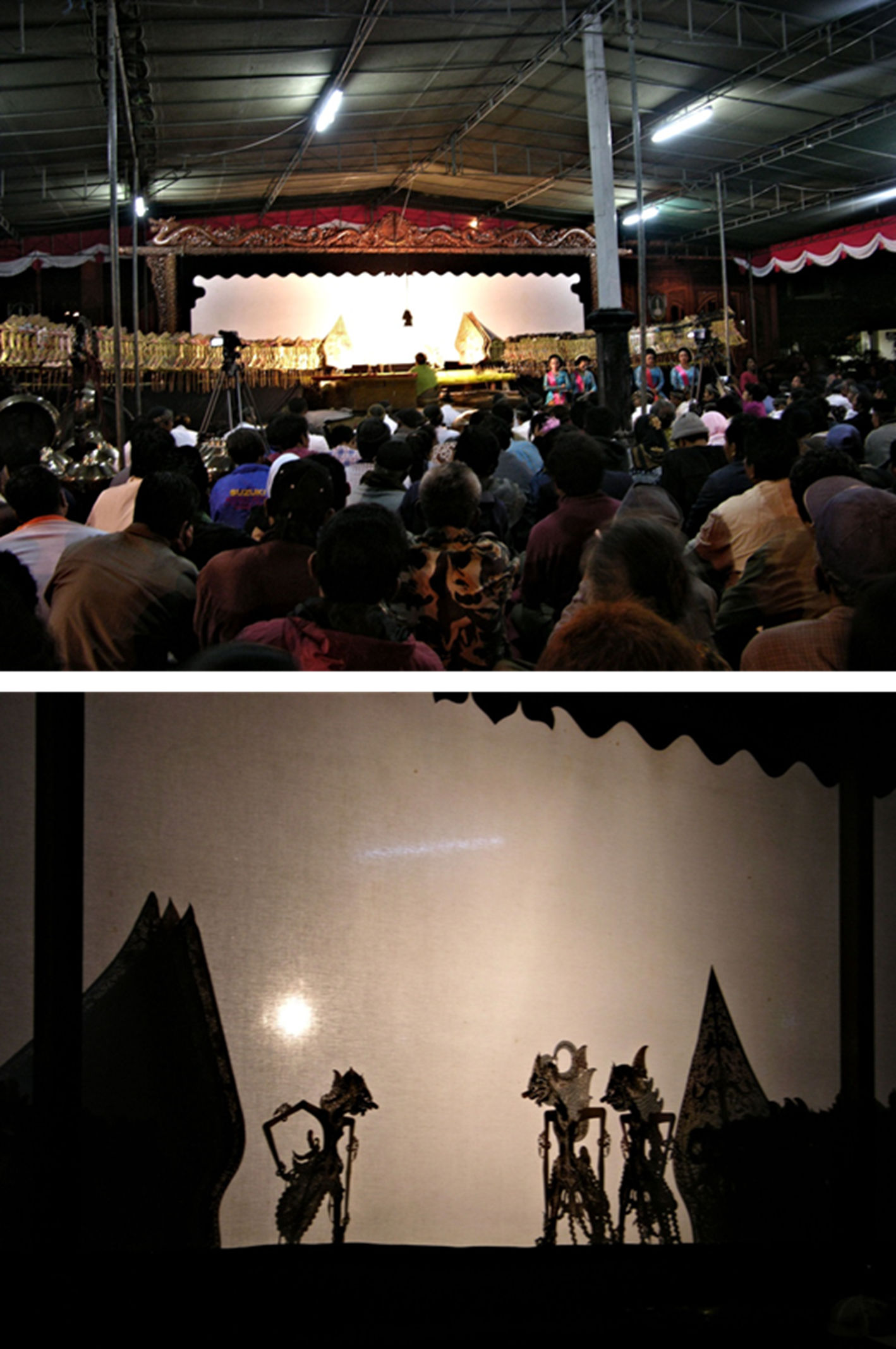

Wayang kulit show in the Sonobudoyo Museum Theatre, Yogyakarta. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2006.

On the front upper side of the screen, a projecting bulb hung. The front side of the screen was the stage for a gamelan orchestra where various exotic instruments were arrayed. Most of them were percussion instruments that included large and small gongs hanging from frames, xylophones with large keys (gambang) and sets of bowls turned upside down (bonang and kenong), all of them apparently made of brass, as well as several drums (kendang) that more or less resembled Japanese traditional hand drums. Wind instruments and string instruments were not many and some bamboo-made flutes (suling), similar to the Western recorders, and fiddles (rebab), similar to Chinese erhus, were seen. I sat in a seat and looked at the brochure in which the abstract of the day’s show was written in English. It was a part of the popular Ramayana story, such as follows.

“Prince Rama of Ayodja married Princess Sinta winning the archery contest to choose the princess’s husband. In a forest when she was charmed by and chasing a golden dear, the incarnation of a maid of demon king Rawana, she was kidnapped by Rawana who disguised himself as a monk. Rama and his brother, Laksmana, who went for search met a white monkey, Hanuman, and got the monkey king Sugriwa on their side. Following the clue obtained by a bird, Sempati, who was the charioteer of Sun God, Hanuman jumped across the sea to Langka Island and found the prisoned Sinta. Rama’s armies crossed the channel along a causeway constructed by the monkeys to attack the evils. Finally Rama shot Rawana to death and rescued Sinta.”

Soon, musicians dressed with batik sarongs and caps of brown, black and white colours started the tuning-up and several female singers dressed with colourful batik sat square on their positions. At eight o’clock, no sooner than the room light was dimmed and the gamelan music started, the dalang (master puppeteer) in the same batik as the musicians who sat in front of the screen picked up a puppet, called “gunungan”, which represented the sacred mountain, Semeru (equivalent to Sanskrit Mahameru and Japanese Miyaukau), leant it against the middle position of the screen and solemnly offered an invocation. The puppet is alternatively called Kayon, which means the tree of life. The dalang picked up different puppets one after another and, while skilfully manipulating them with both his hands, he read both the narrative parts and the characters’ parts as gidayu, the master of Japanese Ningyo-joururi .His low voice sounded rhythmic. Later I learnt the text was a type of verse called Kakawin. In the brakes of sections, the female singers sang songs in slow and high-tone voice.

The rear of the partition, which should be the proper side to watch shadows, was a fantastic different world, despite that it was separated by a thin sheet, where the only rectangular screen was light in the darkness and not only the outlines of puppets but also numerous small holes perforated on the leather were vividly projected. The colours painted on leather sheet were faintly seen on the shadows, passing through the semi-transparent buffalo leather. In such a scene as two characters held a dialogue, only the hands of the shadow moved in a delicate manner, but once a battle started, the whole two shadows lively ran all around the screen, shifting their positions and jumping into the air with their arms swinging to attack the opponent. The outline of characters was occasionally blurred, adding some effect to the shadow, as the puppets were moved a little away from the screen by the dalang. The voices of characters as well as the intoned narration were in Javanese language which was not understandable. I thought even the Japanese joururi is not easily followed if one is not familiar with the semi-modern language and the story of titles.

Thus the performance of one and a half hours went on while I was absorbed in it as if I were in a dream. How was the lively shadow produced from leather-made puppets, which were finely prepared but looked rather grotesque in daylight? Not only the puppets and the dalang’s techniques but also the text and the gamelang music must have been refined in the long passage of time. My interest became deepened even more.

2. Wayang kulit show hosted by the Solonese Royal House.

Despite chances to see the performance of wayang kulit hosted by a royal family being scant, I luckily had an occasion in Solo (Surakarta), the capital of the House of Susuhunan, located fifty kilometres to the east by northeast of Yogyakarta, that is actually the head family from which Yogyakarta’s House of Sultan had branched. Although the purpose of my trip to Solo was to visit the excavation site of Java Man at Sangiran in a suburb of the city, it was incidentally the eve of the Festival Keraton Nusantara V (The Fifth Festival of Palaces in the Archipelago) was scheduled on the next day.

In the alun-alun (square) in front of the city hall a large wayang stage with a roof, which looked too good for temporary use, had been constructed for the eve of the festival. In front of the huge screen was a large-scale gamelan orchestra. The title of the evening’s show was the Bharatayuddha, the tragic and horrible story of the final war between the Pandawa and the Korawa families, derived from the Mahabharata and written in Java.

Wayang kulit, “Bharatayuddha”, performed on the eve of Festival Keraton Nusantara V (The Fifth Festival of Palaces in the Archipelago), at the square in front of the city hall of Solo. Top: Front view. Bottom: A scene. Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006.

The motion of puppets in the wayang kulit performance looked somewhat slower and more elegant than that in Yogyakarta, as I actually read later in a book that “while the style in Yogyakarta was more orthodox and conservative and the movement of puppets was more vigorous, direct and simple, that in Surakarta style was more sophisticated into delicate, refined, and complex manner”. I was only watching the show by vaguely imagining the scenes of the story because the Javanese language was again not at all comprehensible.

The rear of the screen was also full of people. Having looked at the surrounding situation, I realised how deeply wayang was rooted in the minds of Javanese people, despite the chances to see the performance are meagre nowadays. In fact, the puppets of wayang are designed in various items, ranging from interior ornaments to accessories and T-shirt prints, and wayang performances are frequently broadcast on television. I heard that the orthodox wayang performance, such as of that evening, would continue overnight until next morning, but I retired from the venue at around midnight.

3. The origin and the evolution of wayang kulit

The texts of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana played in wayang are not the direct translations of the original Indian versions but indigenous poetry called “kakawin” composed in Javanese language with a strict metre, the first example being the Javanese Ramayana allegedly written during the reign of King Balitung (898 - 910 AD), a king of the Sanjaya Dynasty, which prospered in the 8th–10th centuries in the land of Mataram in Central Java..

Although the capital of Java was moved soon afterwards to the eastern part of Java Island, the tradition of kakawin was inherited and applied in and after the 11th century, not only in such literary works as Arjunawiwaha, Krsnayana (Krishnayana) and others but also such a chronological book as Desawarnana (also called Nagarakertagama) and Pararaton.

When was wayang born? The earliest known record was found in the royal charter issued in the name of King Balitung in 907 AD as inscribed in a copper plate. It was written that when a freehold was dedicated for a local monastery, mawayang (performance of wayang) on an episode of Bima was given for entertainment along with the recitation of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata as well as dances, songs and buffoonery. Whether this wayang was wayang kulit or some other form of wayang was not clear from this inscription, but it was considered to have been the former from some other evidence. For instance, in a paragraph in Arjunawiwaha composed in 1035 AD it was written that “They [spectators] cry and are sad, knowing that it is merely [the illusion of] carved leather that moves and speaks”. Also, in Bhomantaka (The death of Bhoma), another kakawin composed by an unknown author in the Kediri Era (1042–1222 AD), there were such sentences that “Seeking shade in the clouds they were now indistinctly visible, then reappeared like wayang puppets projected against a white screen, the light of the sun serving as the stage lamp”, “The rice fields were shrouded in a haze, as though hidden behind a kelir [screen]. The banana trees moving gently resembled wayang puppets”, etc. From these facts, it is almost certain that wayang kulit had existed at the latest in the early 11th century

Then, where did the idea to project the shadow of puppets come from? A theory has it that ancient people in Java would have thought in their animistic belief that the souls of their ancestors were brought to life in shadows and gave them advice and magical powers.

After the 15th century when Islam spread in Java, such an opinion that Moslems had greatly contributed to the establishment of wayang kulit was advanced. It was even claimed; contradictory to the historical facts, that wayang kulit itself was created by Islamic saints. It may not be surprising because there was a misbelief among Moslems that Aji Saka who had brought civilisation to Java in the 1st century AD was actually a companion of Prophet Muhammad who stopped in India en route to Java and that the books of Mahabharata, Ramayana and Arjunawiwaha were authored by Aji Saka who was a Moslem.

With regard to the highly deformed figures of wayang characters in Java, which were passed down to date, a theory says that Sunan Giri, an Islamic saint at the time of Raden Patah who founded the first Islamic kingdom, Demak, in Java in 1475, had ordered an unrealistic puppet set made in order to circumvent the Islamic proscription against the portrayal of human form. Whether this is true or not, it is noteworthy that in Bali, where the penetration of Islam was prevented, the design of wayang puppets is more natural and closer to real human figures, implying that the original form of wayang puppets in Java was supposed to have been similar to those that are still seen in Bali .

Seeing is believing. The Balinese wayang which I saw was quite interesting. A small theatre named Pondok Bamboo was found in a street of Ubud, a famous art village. In a humble one-page brochure given together with the ticket at the reception under the eaves of the theatre was such guidance that wayang kulit bore the characteristics of teaching, entertainment and religious service and that, in Bali where Hinduism was the major religion, it was commonly performed on such occasions as temple festivals, wedding parties, birthday celebrations and funerals. The guidance was followed by the abstract of the day’s turn, entitled “A story from Mahabharata”. It read,

Comparison of Wayang kulit puppets of Java (left) and

Bali (right). Top: The character is Arjuna for both. Bottom: Kayon (Tree of

life) which is also called Gunungan (a mountain motif). Images reproduced from:

http://tokohwayangpurwa.blogspot.jp

.

“When the King of Pandawa built a new palace, Puri Kandawa Prasta, he invited King Krsna to receive advice for the inauguration ceremony, called Raja Suya. Krsna departed for a journey to receive support from neighbouring kingdoms, accompanied by Bima and Arjuna of the Pandawas. When they arrived at Magada Kingdom, King Jara Sanda was conducting a human-sacrificing ceremony every day according to the teaching of Brata Warsa. Disguised as mendicants, they entered the palace to try to persuade the king to stop the wicked ceremony, which was opposed to the teaching of Siva, but they had to take off their coats, as Jara Sanda did not listen to them and became enraged. A war was inevitable. After a fierce battle, Jara Sanda was defeated by the Pandawas.”

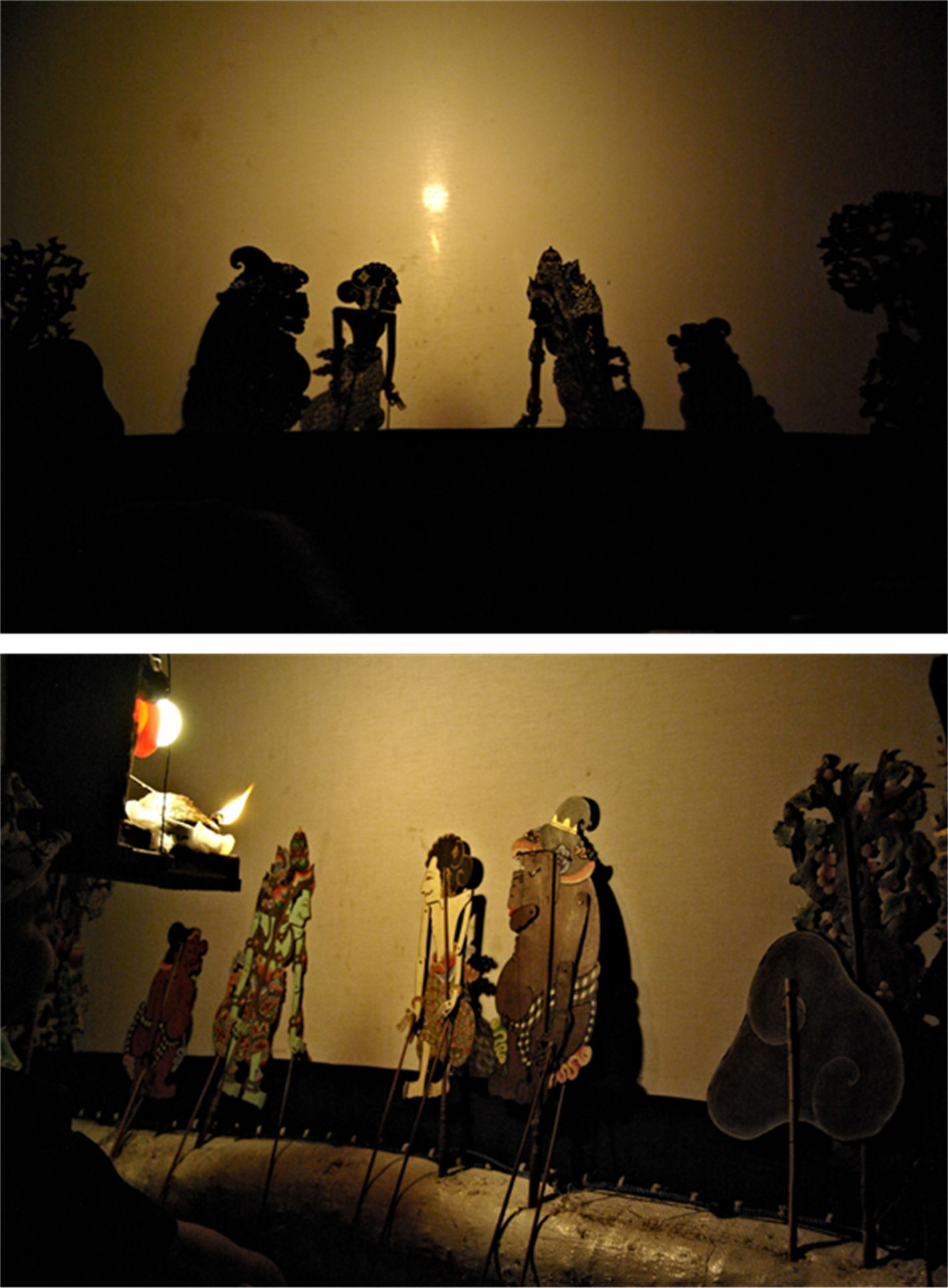

The difference of the Balinese wayang kulit from the Javanese version was not only the feature of puppets and the shape of gunungan (kayon). The sizes of both the screen and puppets were smaller than those of Java. The motion of puppets was more wild and dynamic and the shadows on the screen were dimly wavering. In the rear, although the manner of the dalang to speak both narrations and words of characters were the same as in Java, he did not pick up puppets himself but two assistants who sat on both sides handed them one after another. The light source for projection was a coconut-oil lamp, although an auxiliary electric lamp was devised. The gamelan consisted only of two gambang (large brass-made xylophones), played by two musicians, and no singers were there, unlike the full-orchestra gamelan in Java. This scene was virtually the same as was painted in an old picture that I saw in a book. Since the performance was aimed at sightseers, the dalang inserted some ad-libs in English with deliberate Balinese accents. Thus the show finished in one hour in a friendly atmosphere.

A scene of Balinese wayang kulit. (Top) Shadow side, (Bottom) Backside. Photographed at Pondok Bamboo Theatre, Ubud, Bali, by M. Iguchi, February 2012. Note that the figures in the shadow are left-right reversed.

Apart from the aforementioned arguments, it was after the foundation of the New Mataram Kingdom in the early seventeenth century by Panembahan Senopati, who unified small kingdoms coexisting after the fall of the Majapahit Kingdom, that wayang kulit was developed into a sophisticated style and moveable arms were invented. After the branching of the royal house into the House of Susuhunan in Solo and the House of Sultan in Yogyakarta in the middle of the 18th century, wayang was cherished in the two royal houses and brought up into the present elegant art. Although it was one side of the history that the division of the kingdom in 1755 AD, arranged by the arbitration of VOC after the three-time Wars of Succession, had enhanced the presence of the Dutch in Java, it was undeniable on the other side that kings and nobles were freed from military matters and became able to concentrate on the development of their own art and culture. It was also in the courts of Solo and Yogyakarta that wayang wong (human wayang) was established.

The Royal Houses as well as nobles, the bulwarks of the throne, are paid respect to by common people even after the country became independent as a republic.

In Part 2 (November Issue, 2016), “Wayang World” which includes various plays derived from wayang kulit will be discussed.

[Part2]

4. Wayang World

(1) Expansion of the repertory of wayang.

Continued from the October Issue, 2016.

The theatre of wayang kulit had generated various derivatives to form the so-called “wayang world”, the word, wayang, which literally meant “shadow”, having been applied to various plays other than wayang kulit.

Wayang kulit itself, which traditionally played such classic stories as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana which are now called “wayang purwa” (lit. original wayang) had been applied in the 15th–16th centuries in East Java to perform the Panji Stories and Damar Wulan Legend, classified as “wayang gedog”, and in the court of New Mataram a new repertory called “wayang madya” to play episodes of former kings, viz. King Jayabaya of Kediri, was added. In addition, wayang kulit based on the history of Yogyakarta (Wayang kuluk) and that of Solo were created. The activity of Prince Diponegoro, the hero of the Java War (1825–30), was made into Wayang Jawa. In the later centuries, wayang was further used for the teaching of the Catholic religion. After the independence of the Republic of Indonesia, it was applied for the spreading of Pancasila (the state ideology). Wayang to play such a fable as “mouse and deer” was also born, as I actually saw several pieces of animal puppets in the Yoshichika Southeast Asia Collection (not open to the public) in the storehouse of the Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya, Japan. Nevertheless, wayang purwa is still beloved by Javanese people, while those new wayang kulit have almost diminished.

Left: A scene of wayang wahyu (Revelation shadow play) of the Saint Paul Story held in the Easter season in 2012 at Solo. (Image from: http://www.hidupkatolik.com/2012/04/18/solo-jawa-tengah-wayang-wahyu-paulus. Right: One of Wayang Wahyu puppets (Jesus) owned by Pangudi Luhur Primary School, Suraka (Solo). Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012.

According to the schoolmaster, Br. Aloysius Istiyanto, FIC, Wayang Catholic, formally called Wayang wahyu (wahyu=revelation) is played in the Christmas and the Easter seasons.

(2) Wayang kelitik

“Wayang kelitik” or “wayang kerucil” was a kind in which the design of puppets was similar to that of wayang kulit but the bodies were made of wood board and colourfully painted. Although puppets were manipulated by holding the main axis and moveable arms, this wayang was not aimed at casting a shadow but showing the substance itself, contrary to the description in Internet articles or even in books. Wayang kelitik was presumably originated and popular during the Majapahit Era (1293-1520) in East Java but became unpopular in the later time.

I have seen an old 16 mm movie films filmed in the 1920s in Java by Marquis Tokugawa as well as a set of wayang kelitik puppets. In the shot of wayang kelitik performance in it, there was no screen to project shadows in front of the puppeteer. A still image of the scene was inserted in the “Journeys to Java’.

Puppets of Wayang kelitik (from Yoshichika Southeast Asia Collection). By courtesy of the Tokugawa Art Museum.

Wayang kelitik, probably performed when Marquis Tokugawa visited Java in 1920s. Duplicated by courtesy of the Owari-Tokugawa Family from the first issue of Marquis Tokugawa, Jagatara Kikou (Journeys to Java), Kyodo Publishing, Nagoya, 1931. Note no screen to project shadow is seen.

(3) Wayang golek

One more wayang played with puppets is “wayang golek” in which three-dimensional figures are employed. The structure of puppets is composed of a wooden cylindrical body, in the centre of which is passed an axis to turn the head fixed on its top, and two arms that hang down from the shoulders are moveable by narrow rods like those of the wayang kulit puppets. The upper and lower parts of the body are dressed with batik-made kubaya (blouse) and sarong (skirt), respectively. Although the origin of wayang golek is not sure, it is said that a prototype arrived from China was first adopted to play Menak Stories, the stories of Amir Hamzah (Agung Menak in Java) who was an uncle of Muhammad, in the Islamised towns on the north coast of Java in the 17th century. Then, the repertory was expanded to cover the Ramayana and other classic titles and the show became popular particularly in West Java. Although the puppets of wayang golek are abundantly sold as souvenirs in department stores and other shops, wayang golek is rarely performed today. I have once seen only a short performance of some fifteen minutes demonstrated for tourists in a hotel in Bandung.

Puppets of wayang golek (from Yoshichika Southeast Asia Collection). From the patterns of the puppets’ dresses, these are considered to be high-grade pieces from Yogyakarta, not from West Java. Note that the rods to manipulate hands have been removed. By courtesy of the Tokugawa Art Museum.

(4) Wayang beber

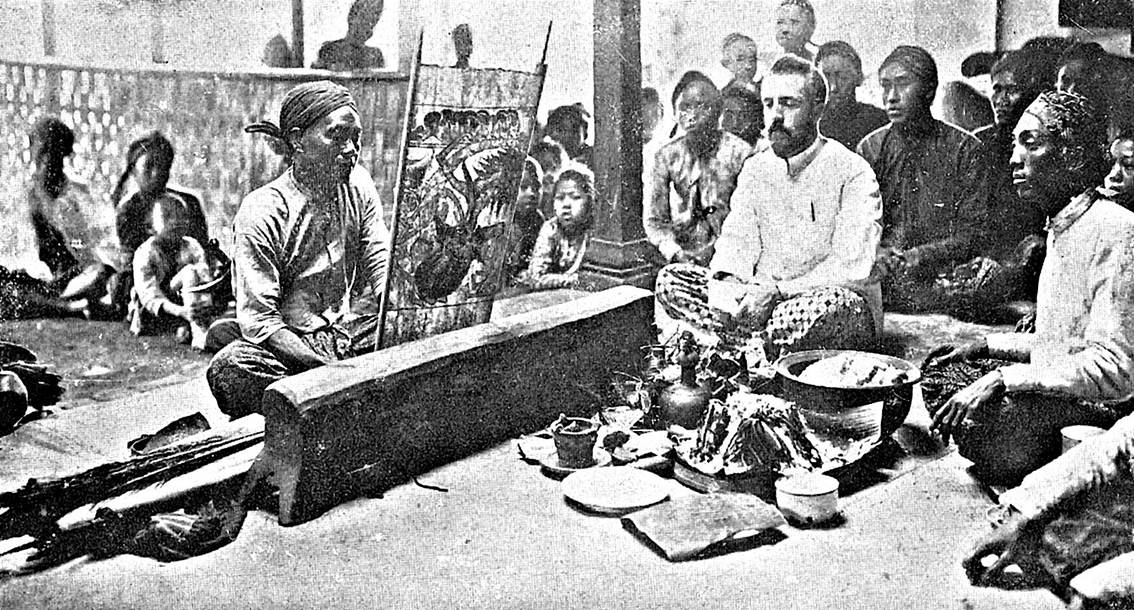

There was a different type of wayang called “wayang beber” in which a dalang read a text, while rewinding a picture scroll held upright between two poles. Although some people assume that its origin was older than wayang kulit and dated back to the 4th or the 5th century, it is generally agreed that it was after the 12th century when the Panji Stories, the Mahabharata, the Ramayana and other stories were adopted. Wayang beber must have been popular in the Majapahit Period as it was written in The Overall Survey of the Ocean Shores (瀛涯勝覧, Ying ya sheng lan, 1416) by Ma Huan (馬歡) who accompanied the great voyage of Zheng-He (鄭和) in the Ming Period China, but it had gradually declined in the later time and we could only see the scene of its performance in photographs taken in the early 20th century. The sheet used for the picture scroll was a bark-sheet called “daluang” prepared by elaborately hammering the white inner-bark of paper-mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera). Daluang was used also for books but not as much as lontar to be mentioned in the next section. While daluang as well as lontar were obsolete after the introduction of pulp paper and its manufacturing technology, some efforts to revive and conserve the traditional technology are made today as I have seen a display in an exhibition held in the Paper Museum, Asukayama in Tokyo in a recent year.

Wayang beber performance. Duplicated from W. F. Stutterheim, Pictorial History of Civilization in Java. Translated by Mrs. A. C. Winter Keen, Java Institute and G. Kolff, 1927

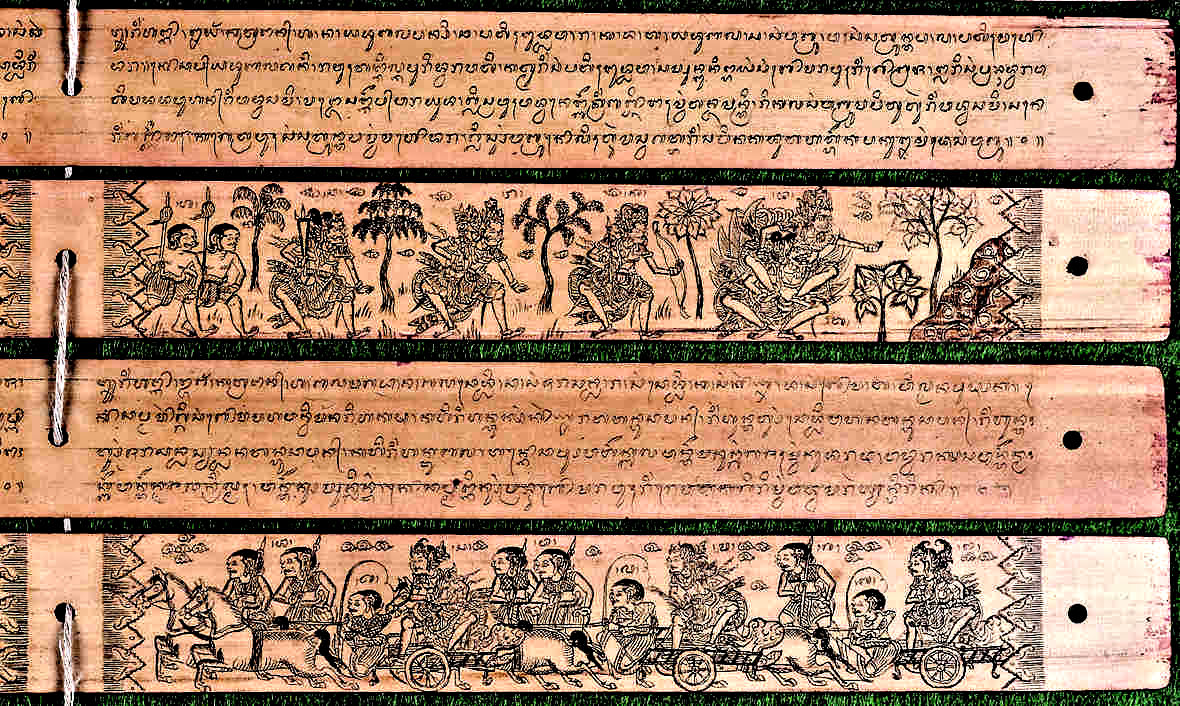

(5) Illustrated Lontar

It may be better classified into the category of a picture book rather than that of wayang, but there were lontar documents in which not only the text but also illustrations of a story were inscribed, as we often see some pieces in museums. Lontar itself was a leaf of lontar or siwalan palm (Borassus flabellifer), cooked in water containing turmeric as an antiseptic, cut into a strip, and pressed, on which letters and/or pictures were inscribed and filled with a compound of soot and oil; the strips were bunched like a Venetian shade. They say lontar is still of use in Bali. An antique piece that I obtained in the courtyard of Bali National Museum in Denpasar from a pedlar was a souvenir article probably produced in the early last century. The set consisted only of eight leaves, on each of which were engraved a scene of Ramayana in the middle and a short Javanese or Balinese text and its English translation on the left and right sides, respectively. In the case of complete books of long kakawin, several hundred or more leaves were needed. .

It is hard to imagine how people of old days were skilful and perseverant to inscribe fine letters and pictures on such many leaves. Lontar of Bhomakawya (Bhomantaka) held in the National Museum, Jakarta is an example.

Lontar of Kakawin Bhomakawya (Bhomantaka) held in the National Museum, Jakarta. A part of image presented by courtesy of The Lontar Foundation (Jakarta).

Just for reference, the young fruits of siwalan palm are edible and nice, the texture and taste of which being more of less similar to lychee.

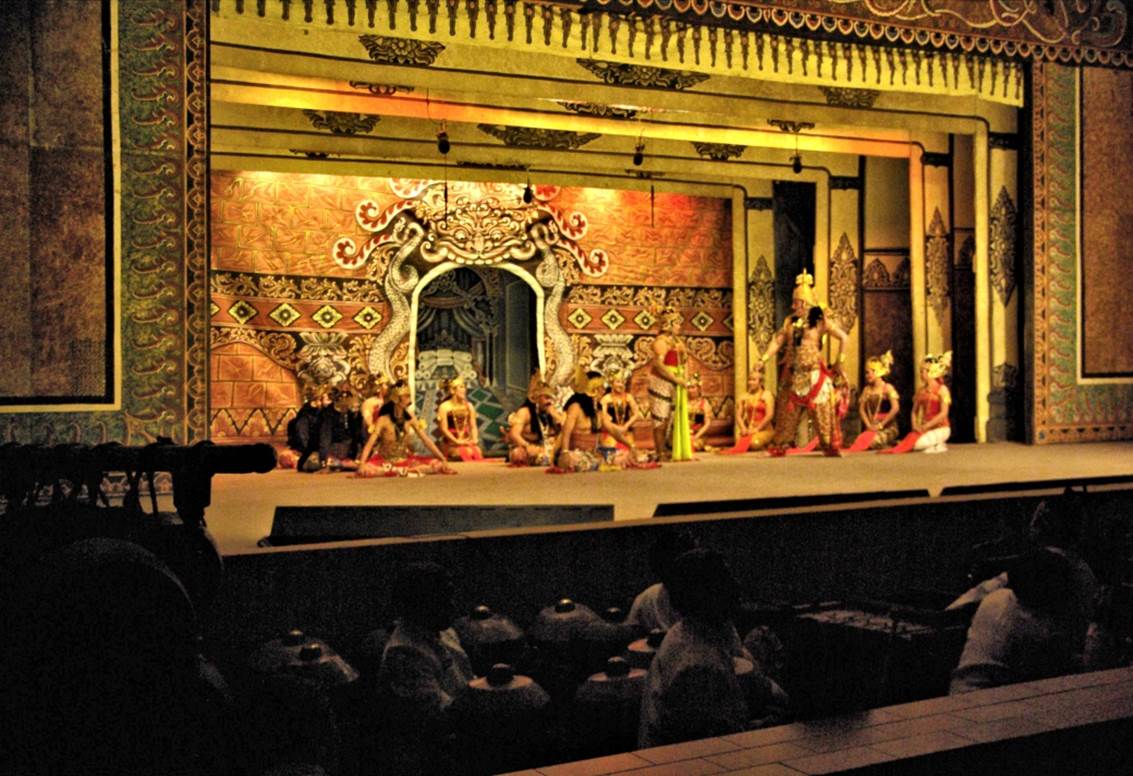

(6) Wayang wong, a stage-play

As aforementioned, wayang wong played by male and female actors was established in the courts of Solo and Yogyakarta. Although the script is kakawin and the play is accompanied by orchestra as in the case of wayang kulit, the dalang reads only the narrative parts and the actors and actresses speak their parts.

Traditional theatres which had once existed here and there were closed with the emergence of cinemas and television. The performance of wayang wong can be seen today in amphitheatres in Prambanan in the outskirt of Yogyakarta and inside of the city but the programme is always some extract from the Ramayana that is familiar to sightseers as the performance is advertised as “Ramayana Ballet”.

Having been informed that one authentic theatre survived in the Royal Sriwedari Park Solo, I visited there. In front of the ticket office were signboards for announcing the programme, “Today is Citrawangi” and “Tomorrow is Tunjungsari” and on the front wall was a notice board was a list of monthly programme.

On the stage in the theatre, there was a curtain on which a large gunungan (kayon) was dyed and above the curtain hung a drop curtain on which the head of Kala was woven. The floor of gamelan was situated in front of the stage at the lower level. Among the audience, there were a few groups who were apparently visiting foreigners, but others were local fans. Before the scheduled opening time of 8 pm, about half of the seats were full, despite it being a weekday evening.

When the curtain opened, a flat curtain on which the outer wall of a castle was brightly painted appeared in the back of the stage, but there were no stage settings. About ten actors and actresses acting as princes, princesses and nobles in battle costumes emerged. Although their dresses and accessories looked similar to those of Ramayana ballet dancers, which I had seen in the amphitheatres in Prambanan and Yogyakarta, their carriage looked to be slower and more graceful, as if the show was an orthodox stage drama rather than a ballet. Without understanding their speech, I guessed it was the scene of a ceremony held before going to war.

Wayang wong performance in Royal Sriwedari Theatre, Solo: The first stage of “Citrawangi”. In the low floor in front of the stage was the gamelan orchestra. Photographed by M. Iguchi, May 2009.

The second stage began in a forest with a talk from a female warrior of another clan to monkey troops, with white masks, who were similar to those in the Ramayana story. The third stage was in an open space in another forest where two warriors from the first and the second clans fought furiously with their knives, but the battle ended in a draw. In the fourth stage two female warriors from the two clans had a dialogue in front of the gate of a fortress. In the fifth stage, the two women fought and the one from the first clan was killed but, after then, the second woman held the body of the opponent on her lap in sorrow, while men and women of both sides were showing their sympathy. Thus the show of one and a half hours ended while I was not able to understand the full context.

The Citrawangi must be taken from a certain classic story but the source was unknown. For reference, the programmes of the next and previous evenings, Tunjungsari and Srikandi Edan were episodes from the reign of King Kertanegara during the age of Singasari Dynasty and from the Bharatayuddha, respectively.

The programme of wayang wong when I visited Solo a second time was “Basudewa Karma”. Since I had no information beforehand, I could not understand the story once again as on the previous time. After returning home, I found an abstract and learnt, with reference to the pictures taken at the theatre, that it was a story of Prince Basudewa of Madura who fought with rivals and eventually got married to Princess Dewi Badrahini, a daughter of Prabu Badrawinata. It was probably not only me who wished the theatre would have provided a brochure, even a simple one, in which the abstract was given in English or the common Indonesian language for visitors who were unfamiliar with Javanese.

One of the features of wayang wong in comparison with Japanese Kabuki and European stage plays was that no stage settings were used and they were painted on the background curtain whenever necessary.

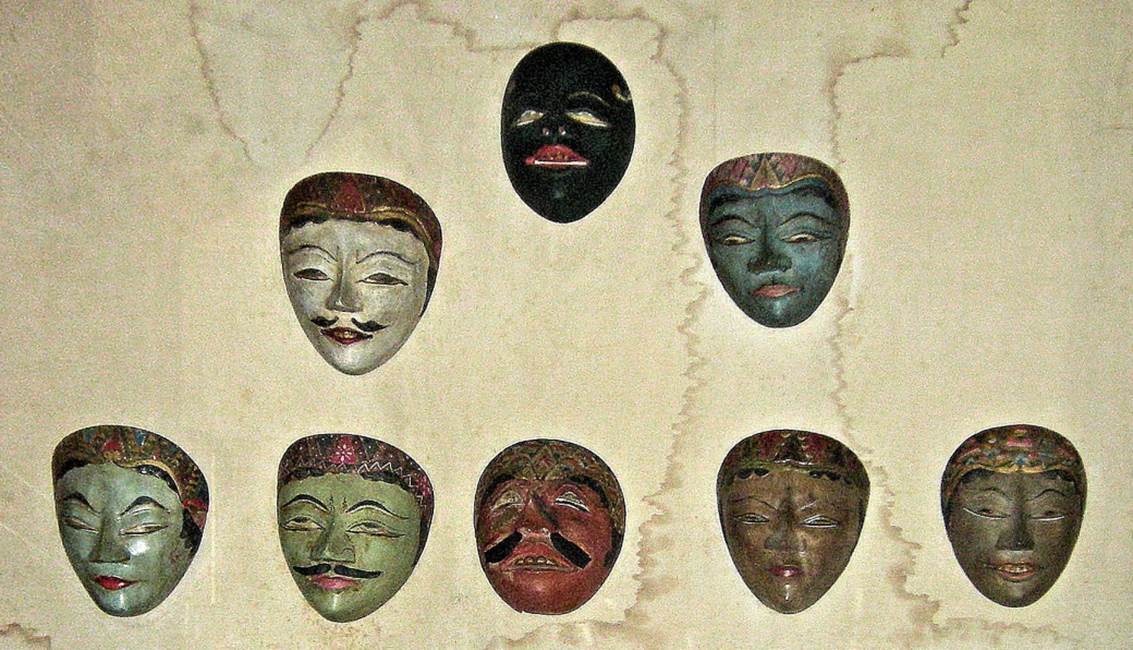

Among wayang played by human is a masque called “wayang topeng”, which must be older than wayang wong, as its major titles were the Panji Stories. Up until today, this play has survived in Bali, although I have not had a chance to see it, while it has long been lost in Java, neglected by the courts of Solo and Yogyakarta.

Masks for Wayang topeng. Photographed with permission in the Bali Museum, Denpasar, Bali, by M. Iguchi, February 2012.

(7) Stage-plays in royal courts

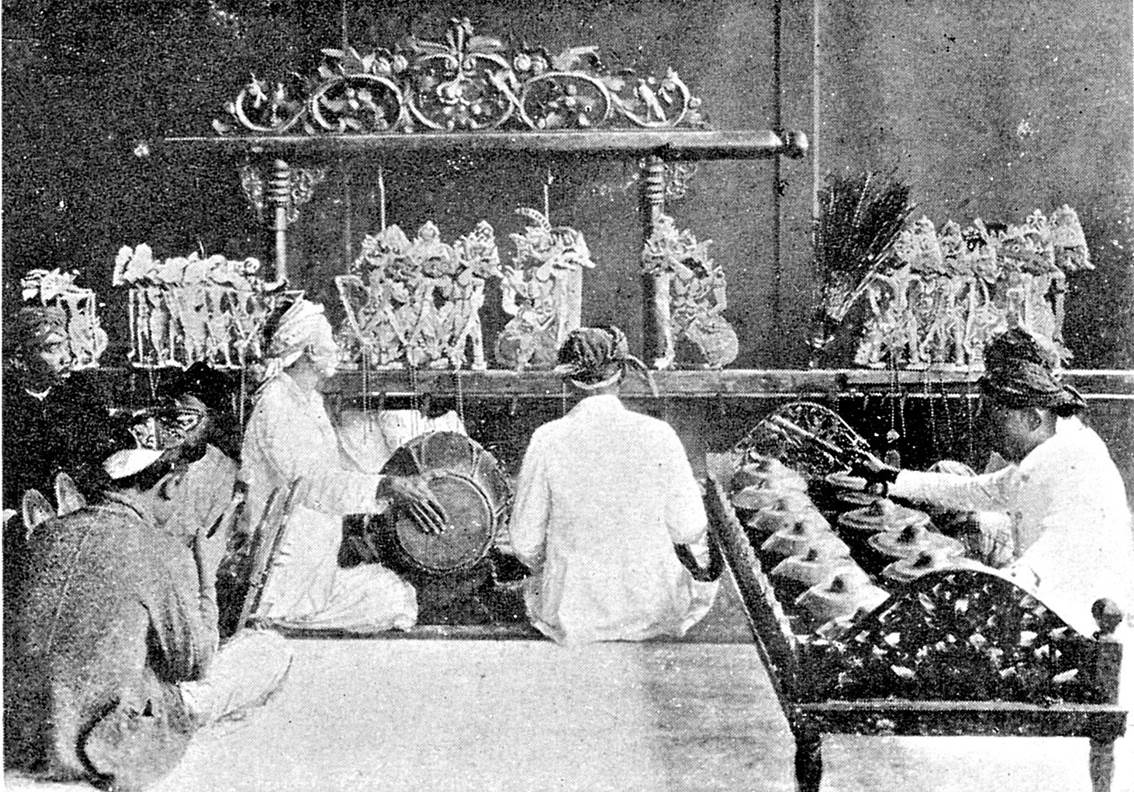

While it is impossible for commoners to see a wayang wong performance held in royal courts, Marquis Tokugawa was invited in 1929 to the palaces of both Yogyakarta and Solo and left a report on the play and the atmosphere in his Journeys to Java as follows:

“Two pairs of actors appeared on the stage from the left and the right sides, hanging their heads down. There were no sounds in the huge hall and a solemn air filled the space, giving me a sober feeling. The calm was broken, when the king ordered, ‘Start!’ The dalang replied, ‘Oh!’, slowly opened the book and began to read the text. The story was a chapter of Ramayana. Then, the music started and the singer sang. (Yogyakarta)”

“When the tone of the gamelan changed, two young men with gorgeous clothes stepped gently into view from the far end of the corridor. One could be assumed to be about twenty-one or two and the other, seventeen or eighteen years of age. After they prayed for a while sitting on the floor, pressing their hands and hanging their heads, they raised their heads and stood up slowly with the music to start to dance. They each put a gold bird-shaped helmet on their heads, gold armour similar to the wings of butterfly on the backs of their half-naked upper bodies and a keris with numerous inlaid gem-stones which shone brightly under the light. I was impressed not so much by the beauty of their costume but by the appearance of these young men who looked so noble and handsome. The eye-shadow at the corner of their eyes added accent to their beauty. In front of the dazzling brilliance of the young men, even those female dancers who overshadowed ‘the three-thousand maids serving in the court’ must be eclipsed, just as stars were against the moon. I watched quite absorbed, like a man who had lost his soul, in such a way as my face must have looked odd to other people. When I came to myself, the prince in the adjacent seat tapped on my shoulder, and told me, ‘They are my brother and son.’ I had thought they were not common people and, in fact, they were princes. What splendour! The two princes performed a brilliant dance. It was elegant and tender, but it turned to be fearsome, when the scene moved to a battle-field, as the two bodies crossed and the edges of their keris hit and sparkled. The gracefulness was not lost, however, during such actions. The performance ended after the highlight scene and the two young princes retired quietly after giving a round of salutes. (Solo.)”

Wayang wong in the royal court of Solo. One of the photographs presented by Susuhunan X to Marquis Tokugawa when the latter visited Solo in 1929. By courtesy of the Owari-Tokugawa Family.

It is said that the most lofty and sacred of all court dances are serimpi and budoyo danced by female dancers, exclusively maiden daughters of noble bloodlines, the performance of which was only limited at least until recently without being exposed to the public. I had once had a chance to see the dance of serimpi at a dinner show in a hotel in Yogyakarta, but it was a short demonstration version of only some fifteen minutes by two dancers and my memory is quite vague.

In the Marquis Tokugawa’s Journeys to Java, the performance of serimpi and budoyo was also written.

It was pointed out in a book that “the Javanese theatre embodies spiritual and cultural values of deep significance; only the No-gaku of Japan can be compared with it, and even so the Javanese has a wider range of theme and is far more than an exquisite survival.” Noh or Noh-gaku established by Ze-ami Motokiyo (1363?–1443?) during the era of Shogun Yoshimitsu Ashikaga in the early Muromachi Period was protected during the Yedo Period by Shogun and other clans as ceremonial play of warriors and performed on special occasions in their houses. If I was to supplement, Ga-gaku promoted in the Imperial court since ancient time could belong to the same category.

Note

Since this manuscript is aimed at a sort of reading matter, specific references have not been given.

Readers is asked to see the details in:

(1) 井口正俊著「ジャワ探究:南の国の歴史と文化」,丸善プラネット刊, 1913 (Masatoshi Iguchi, “Java quest -The History and Culture of a Southern Country”, Maruzen Planet, Tokyo, 2013).

(2) .Masatoshi Iguchi, Java Essay -The History and Culture of a Southern Country, Troubador Publishing, UK, 2015 (ePub edition available from Amazon.com, etc.)/

(3)Marquis Tokugawa(Translated by M. Iguchi), Journeys to Java, ITB Press, 2004: HTML Edition:www.maiguch. sakura.ne.jp.

The Brief History of Java, from (1) and (2) are included in the author’s website, www.maiguch.sakura.ne.jp/.

Author:

MASATOSHI IGUCHI, formerly a technical official in The Agency of Industrial Science and Technology, Ministry of International Trade and Industry, Japan. Dr. of Engineering (Textile Engineering), Tokyo Institute of Technology 1966. Email: maiguch@gmail.com. Formerly engaged in research in polymer science. After retirement, studying the history and culture of Java. Used to play the game “Go” (Amateur 6th dan/ 1966).