Flowers of Java – Poetry and Theatre

Ramayana ballet at Prambanan Amphitheatre

Let us begin with the theatre by reversing the terms of the chapter title. The principal city of Java, Yogyakarta [1], is not only the centre of administration, commerce and education but also the garden where beautiful flowers of Javan culture bloom around the keraton (palace) of the Sultan, a branch of the royal family of Java. The city, geographically located in a wide plain fanning to the south of Mt. Merapi, is not far from such famous ancient remains as Borobudur and Prambanan temples, built in the 9th–10th centuries, which are the primary attractions for sightseers from both other parts of Indonesia and foreign countries.

It was one quarter of a century ago in the 1980s when I went there for the first time for the purpose of visiting Gajah Mada University that I was invited to “Ramayana Ballet” in the weekend evening. The place I was taken to, with no previous knowledge, was an amphitheatre situated in the field of Prambanan. Despite that the performance was said to be held on moonlit nights, the whole surroundings were in pitch darkness because of the thick clouds in the sky, and beyond the lighted stage of the open theatre was seen several candis (temples) of Prambanan, which I had visited in the daytime, dimly illuminated with floodlights, furnishing a fantastic atmosphere. On the left-hand side of the theatre’s stage was a traditional Javanese music band of some twenty members, called gamelan, although the details of their instruments were not observable from our stands. When the overture of a low and slow melody started and the intoned narration by the stage master, called dalang, followed, dancers of both sexes dressed over their bodies with shining gold accessories appeared and danced elegantly. The dancers also spoke their parts when their motion halted. Although the language spoken by the dalang and dancers was Javanese, which was not comprehensible at all by foreigners, it was fortunate that Mrs. W. in an adjacent seat who accompanied us from Bandung was originally a native of Java and kindly explained the scenes to me in a low voice.

Rama, the hero of the story, an alleged incarnation of Vishnu was an intrepid young prince who wore a wonderful helmet on his head, held a bow in his hand and carried a bunch of arrows on his back, whilst his wife, Sinta was a slender pretty princess. In a forest, Laksmana, Rama’s brother hurt Surpanakha, a sister of the demon king Rawana, who had approached him. In revenge for it, Rawana sent a maid who had transformed herself into a golden deer to attract Sinta and, while Rama was chasing the deer to catch it for Sinta, Rawana in disguise of a Brahman kidnapped Sinta. [2]

While I was absorbed in the stage, imagining the world of ancient India, and the story reached its climax, heavy rain suddenly came to stop the performance and eventually forced the rest of the ballet to be cancelled.

On our way back, I told my impression to Mrs. W. and asked her some questions.

“As far as I learnt in school, the Ramayana was an ancient Hindu story. It does not look to fit the present-day Indonesia where the kings and the majority of people are Moslems, does it?”

“No, whatever was the origin, such stories as Mahabharata and Ramayana were Javanised during our long history. We love them as Javanese literature whatever their very origins were.”

“To me, the dresses and the actions of the dancers looked similar to those depicted on the reliefs of Prambanan Temple, which I saw in the daytime.”

“It would have been so at a glance, but they were actually different in details. The Ramayana ballet you saw tonight was a sort of stage play, which was formally called ‘wayan orang’ or ‘wayang wong’ that means a play by human. It was developed in the 16th century in royal courts. They are different from those that might have existed in ancient India or in the Hindu-period Java. In Java, so-called Javan literature was born in the 10th century and, to show it on the stage, a unique shadow play, which we call ‘wayang kulit’, was invented. After then, it had developed into various forms.”

Wayang kulit performance at Sonobudoyo Museum

It was several years later that I saw wayang kulit, that was to be added to UNESCO’s List of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2003 together with unique Javanese keris (dagger), in the Sonobudoyo Museum near the keraton (palace) of Yogyakarta, where short versions of the shadow play were performed every night. Inside the entrance of the one-storey building with a traditional-style Javanese double roof was a big hall of some fifteen metres square, in the middle of which was a partition with a screen of white cloth measuring five metres wide and one and a half metres high. On the front upper side of the screen hung a projecting bulb and on both right- and left-hand sides of the screen were numerous puppets, as many as several dozen, leant against the lower part of the partition wall. The puppets were, as “kulit” meant leather, flat objects cut out from a sheet of buffalo leather and coloured by paints, and the shapes of characters were significantly deformed. There was a rod handle in the centre of each puppet, and the upper and lower parts of arms were jointed at the shoulder and the elbow so as to be moveable by means of a narrow rod attached at the tip of each hand. The front side of the screen was the stage for a gamelan orchestra where various exotic instruments were arrayed. Most of them were percussion instruments that included large and small gongs hanging from frames, xylophones with large keys and sets of bowls turned upside down, all of them apparently made of brass, as well as several drums that more or less resembled Japanese traditional hand drums. Wind instruments and string instruments were not many and some bamboo-made flutes, similar to the Western recorders, and fiddles, similar to Chinese erhus, were seen. While I was reading the brochure in which the abstract of the day’s show, a part of the Ramayana, was printed in English, musicians dressed with batik sarongs and caps of brown, black and white colours started the tuning-up and several female singers dressed with colourful batik sat square on their positions.

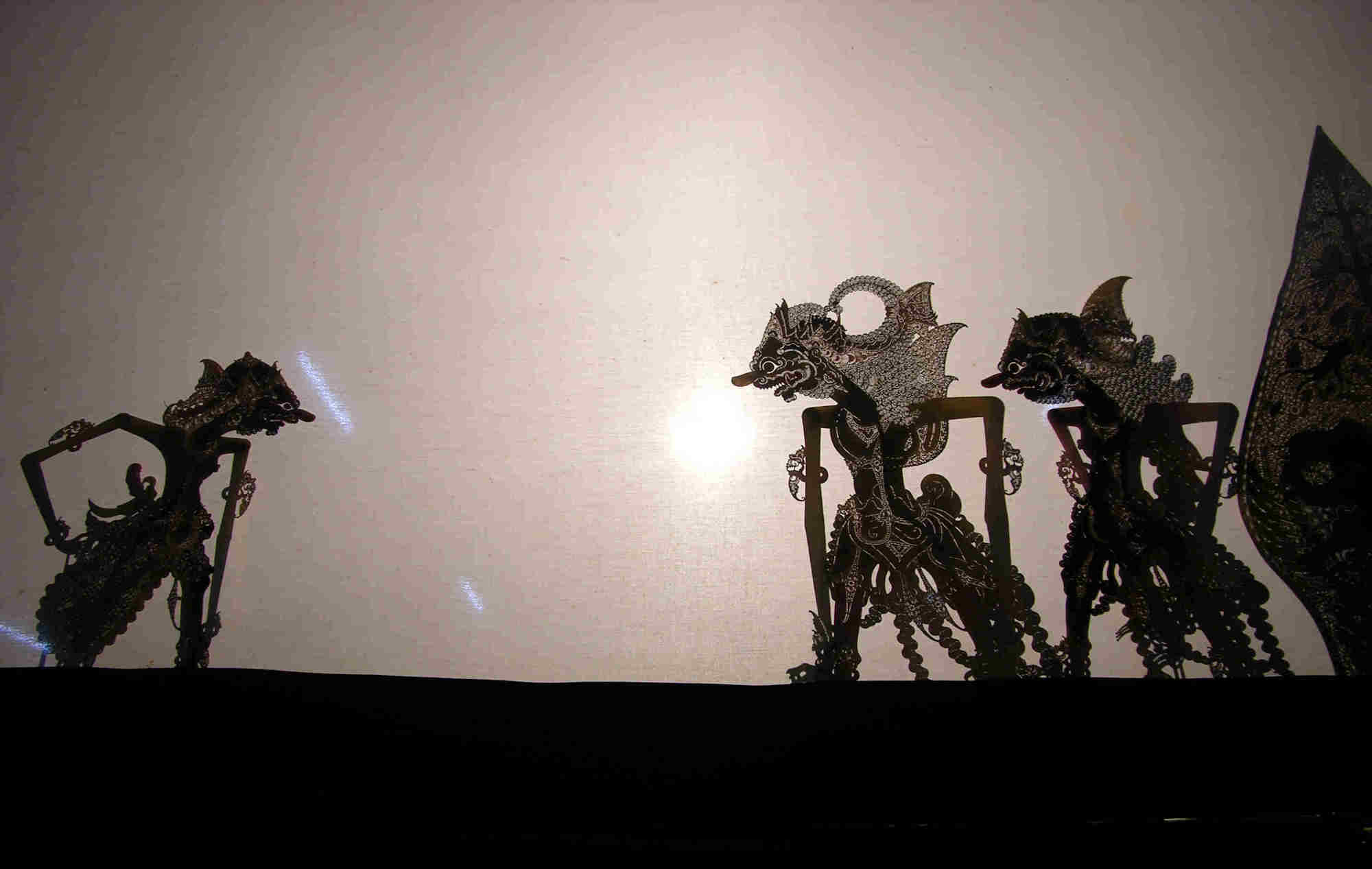

|

Wayang kulit show in the Sonobudoyo Museum Theatre, Yogyakarta. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2006. |

At eight o’clock, no sooner than the room light was dimmed and the gamelan music started, the dalang in the same batik as the musicians who sat in front of the screen picked up a puppet, called gunungan [3], which represented the sacred mountain, Semeru (equivalent to Sanskrit Mahameru and Japanese Miyaukau), leant it against the middle position of the screen and solemnly recited the beginning part of the text. The dalang picked up different puppets one after another and, while skilfully manipulating them with both his hands, he spoke the characters’ parts in different voices.

The rear of the partition, which should be the proper side to watch shadows, was a fantastic different world, despite that it was separated by a thin sheet, where the only rectangular screen was light in the darkness and not only the outlines of puppets but also numerous small holes perforated on the leather were vividly projected. The colours painted on leather sheet were faintly seen on the shadows, passing through the semi-transparent buffalo leather. In such a scene as two characters held a dialogue, only the hands of the shadow moved in a delicate manner, but once a battle started, the whole two shadows lively ran all around the screen, shifting their positions and jumping into the air with their arms swinging to attack the opponent. The outline of characters was occasionally blurred, adding some effect to the shadow, as the puppets were moved a little away from the screen by the dalang. (When I saw the wayang kulit later again, I thought the shadow scenes would have been more fantastic in old days when the projector lamp was not an electric bulb but a flickering oil lamp.) Although the voices of characters as well as the intoned narration in Javanese language were impossible to follow, the performance of one and a half hours went on while I was absorbed in it as if I were in a dream. How was the lively shadow produced from leather-made puppets, which were finely prepared but looked rather grotesque in daylight? Not only the puppets and the dalang’s techniques but also the text and the gamelang music must have been refined in the long passage of time. My interest became deepened even more.

The number of the audience that evening was not more than twenty or thirty, despite the low admission fee that was apparently not sufficient to maintain the theatre. Later, I learnt the traditional theatres in Yogyakarta, as well as in Solo, were supported by the royal houses. Outside of the museum building, there was a small workshop to demonstrate the process of preparing puppets. The cutting of a character’s shape out of buffalo leather and the punching of large and small holes on it were done manually in accordance with the pre-drawn pencil marks, and by the side of the craftsman were partially coloured pieces. It was quite impressive that they needed several weeks to complete one puppet. When I revisited there later, I bought a piece of Bima [4] at the offered price for large banknotes, while asking for a discount was customary in Indonesia, to express my gratitude for the craftsman’s fine work. For reference, most wayang puppets sold at moderate prices on the street of Yogyakarta or in department stores in Jakarta as souvenirs are imitations made of carton paper, which are just good enough to put on the wall as a memory of Java, but not useful for shadow play.

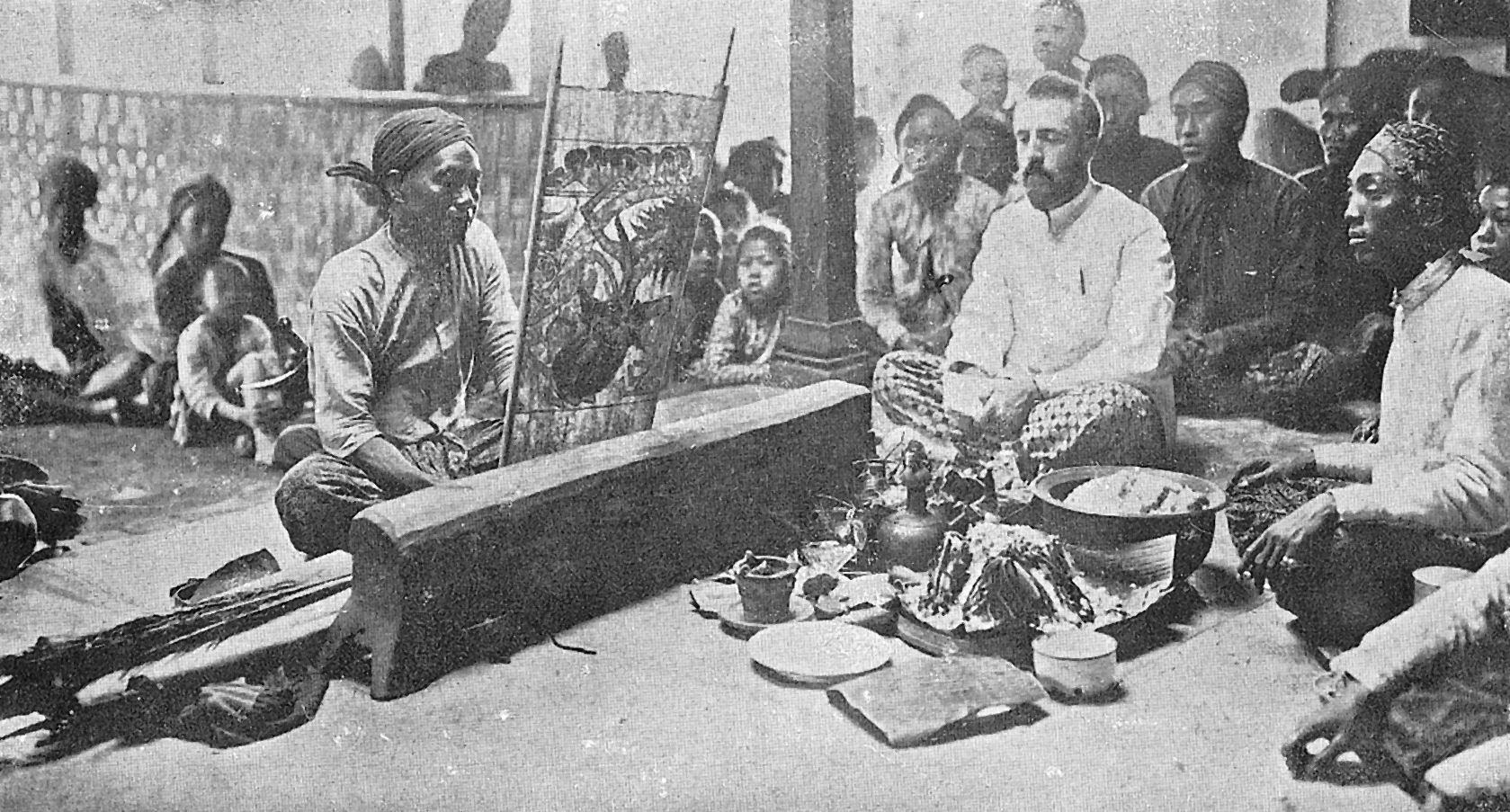

Wayang kulit used to be popular not only in royal courts but also among common people, as a performance held as an attraction on the occasion of a wedding in the countryside was encountered and described by Marquis Tokugawa in his Journeys to Java [5].

Wayang kulit performance hosted by the Solonese royal house

Despite chances being scant, I luckily had an occasion to see the performance of wayang kulit hosted by a royal family. In Java, there is another royal family, the House of Susuhunan, in Solo (Surakarta), fifty kilometres to the east by northeast of Yogyakarta, that is actually the head family from which Yogyakarta’s House of Sultan had branched. It was several years ago when I arrived at the Solo Station after midnight by a night train, with the intention to visit the excavation site of Java Man at Sangiran in a suburb of the city, that it took me two hours, being driven around the town by a taxi, to finally find a small tavern near a bus terminal, because all hotels were unexpectedly full. It was because the Festival Keraton Nusantara V (The Fifth Festival of Palaces in the Archipelago) was scheduled on the next day and all sultans and their parties were gathering in the city.

The eve of the festival was held on the same day in the alun-alun (square) in front of the city hall where a large stage with a roof, which looked too good for temporary use, had been constructed and was brightly lit. When the performance of wayang kulit started, a numerous audience who filled the square was joyfully gazing at the stage and listening to the dalang’s voice. The title of the evening’s show was the Bharatayuddha, the tragic story of war between the Pandawa and the Korawa families, derived from the Mahabharata and written in Java, the story of which I knew only to some extent at that time. The summary of the story, which I read afterwards, is as follows.

|

A scene of wayang kulit, “Bharatayuddha”, performed on the eve of Festival Keraton Nusantara V (The Fifth Festival of Palaces in the Archipelago), at the square in front of the city hall of Solo. According to an expert of wayang, Mr. Djoko Wiryono, father of this writer’s young friend, the character on the left is Sengkini, the minister of the Korawa, and the two on the right are a monster king and his follower. The object on the end of the right-hand side is the so-called Gunungan or Kayon. Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

“The Korawas were the ninety-nine sons of King Dhrtarastra of Hastina, headed by Duryodana, and the Pandas were the five sons of Pandu, the king’s younger brother, namely, Yudistira, Bima and Arjuna from Queen Kunti, and Nakula and Sadewa, twin sons from concubine Madri. Since King Dhrtarastra was blind, the kingdom was governed by Pandu. Thus, the cousins were raised and educated together by common uncles and preceptors, but they were constantly rivalling with each other as the Korawas were always jealous and hated the Pandawas who always proved superior. When the king appointed Yudistira, his eldest nephew, heir to the throne, after the early death of Pandu, the Korawas became angry and devised a stratagem to destroy the Pandawas. The Pandawas managed to escape from it and spent a hard time, disguised as begging Brahmans. When they returned, the Korawas consented to a division of the Hastina kingdom and gave the Pandawas the western part where they built their capital, Ngamarta. The Korawas, not abandoning their intention to ruin the Pandawas, invited Yudistira for gambling and confiscated all his wealth, his kingdom, and his brothers’ freedom. The Pandawas lived in slavery for twelve years and an additional one year among the common people.

“In the beginning of the Bharatayuddha (the last chapter of the Mahabharata), Krsna went to the capital of the Korawas by representing the Pandawas to negotiate the latter’s claim to a part of the kingdom. Although the old king Dhrtarastra and his advisors were supportive, Duryodana rejected it and even tried to kill Krsna, to deny the hope for peaceful settlement. The Great War of the Bharatas between the two cousin groups broke out and a fierce battle continued for eighteen days in the field of Kuru. The events were full of tragic incidents in which the cousins’ old uncles and venerated preceptors inexorably met their death, as did many young heroes, including the sons of Arjuna and Bima. In the final encounter, Arjuna killed Kama (his half-brother from Kunti, begotten by the sun‑god Surya, but sided with the Korawas without knowing of his own origin) and Bima slew Duryodana. Funerary rites were then held for all the fallen warriors, the women lamenting their husbands and sons. Yudistira was crowned the king and reigned in Indraprastha (Ngamarta).” [6]

The motion of puppets in the wayang kulit performance looked somewhat slower and more elegant than that in Yogyakarta, as I actually read later in a book that “while the style in Yogyakarta was more orthodox and conservative and the movement of puppets was more vigorous, direct, and simple, that in Surakarta style was more sophisticated into delicate, refined, and complex manner” [7]. I was only watching the show by vaguely imagining the scenes of the story as the Javanese language was again not at all comprehensible. Even my friend who accompanied me from Bandung said that not all the words were clear, as they were significantly different from those of her native Sundanese language. The rear of the screen was also full of people. Having looked at the surrounding situation, I realised how deeply wayang was rooted in the minds of Javanese people, despite the chances to see the performance are meagre nowadays. In fact, the puppets of wayang are designed in various items, ranging from interior ornaments to accessories and T-shirt prints, and wayang performances are frequently broadcast on televison like Ningyou-joururi (a Japanese puppet show) in Japan. I heard that the orthodox wayang performance, such as of that evening, would continue overnight until next morning, but I felt a little tired and retired from the venue at around midnight.

The origin and the evolution of wayang kulit

The texts of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana played in wayang are not the direct translations of the original Indian versions, as I was told before. The first example of a type of epic called “kakawin” written in Javanese language with a strict metre, was composed [8] during the reign of King Balitung, a king of the Sanjaya Dynasty, which prospered in the 8th–10th centuries. Although the capital of Java was soon moved from the land of Mataram to the eastern part of Java Island, the tradition of kakawin was inherited and applied in and after the 11th century, not only in such literary works as Arjunawiwaha, Krsnayana (Krishnayana) and others, but also such a chronological book as Desawarnana (also called Nagarakertagama).

When was wayang born? The earliest known record was found in the royal charter issued in the name of King Balitung in 907 AD as inscribed in a copper plate. It was written that when a freehold was dedicated for a local monastery, mawayang (performance of wayang) on an episode of Bima was given for entertainment along with the recitation of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata as well as dances, songs and buffoonery [9]. Whether this wayang was wayang kulit or some other form of wayang was not clear from this inscription, but it was considered to have been the former from some other evidence. For instance, in a paragraph in Arjunawiwaha composed in 1035 AD it was written that “They [spectators] cry and are sad, knowing that it is merely [the illusion of] carved leather that moves and speaks”. Also, in Bhomantaka (The death of Bhoma), another kakawin composed by an unknown author in the Kediri Era (1042–1222 AD), there were such sentences that “Seeking shade in the clouds they were now indistinctly visible, then reappeared like wayang puppets projected against a white screen, the light of the sun serving as the stage‑lamp”, “The rice‑fields were shrouded in a haze, as though hidden behind a kelir [screen]. The banana‑trees moving gently resembled wayang puppets”, etc. From these facts, it is almost certain that wayang kulit had existed at the latest in the early 11th century[10].

Then, where did the idea to project the shadow of puppets come from? A theory has it that ancient people in Java would have thought in their animistic belief that the souls of their ancestors were brought to life in shadows and gave them advice and magical powers [11]. Whether this idea is acceptable or not, it is generally believed that wayang kulit was an indigenous invention in Java. Of course, some people suspected that a certain prototype show might have existed in India and been brought to Java, but no evidence to support such a hypothesis was found in India.

After the 15th century when Islam spread in Java, such an opinion that Moslems had greatly contributed to the establishment of wayang kulit was advanced. It was even claimed, contradictory to the historical facts, that wayang kulit itself was created by Islamic saints.[12] [13] It may not be surprising because there was a belief among Moslems that Aji Saka who had brought civilisation to Java in the 1st century AD was actually a companion of Prophet Muhammad who stopped in India en route to Java and that the books of Mahabharata, Ramayana and Arjunawiwaha were authored by Aji Saka who was a Moslem [14].

With regard to the highly deformed figures of wayang characters in Java, which were passed down to date, a theory has it that Sunan Giri, an Islamic saint at the time of Raden Patah, had ordered an unrealistic puppet set made in order to circumvent the Islamic proscription against the portrayal of human form[15]. Whether this is true or not, it is noteworthy that in Bali, where the penetration of Islam was prevented, the design of wayang puppets is more natural and closer to real human figures, implying that the original form of wayang puppets in Java was supposed to have been similar to those that are still seen in Bali[16].

Seeing is believing. The Balinese wayang kulit, which my long cherished dream came true and I saw, was quite interesting. Having been informed that a show was held somewhere in Ubud every evening, I found a small theatre, called Pondok Bamboo, in a street of the city. In a humble one-page brochure given together with the ticket at the reception under the eaves of the theatre was such guidance that wayang kulit bore the characteristics of teaching, entertainment and religious service and that, in Bali where Hinduism was the major religion, it was commonly performed on such occasions as temple festivals, wedding parties, birthday celebrations and funerals. The guidance was followed by the abstract of the day’s turn, entitled “A story from Mahabharata”. While waiting for the commencement of the show, I read, “When the King of Pandawa built a new palace, Puri Kandawa Prasta, he invited King Krsna to receive advice for the inauguration ceremony, called Raja Suya. Krsna departed for a journey to receive support from neighbouring kingdoms, accompanied by Bima and Arjuna of the Pandawas. When they arrived at Magada Kingdom, King Jara Sanda was conducting a human-sacrificing ceremony every day according to the teaching of Brata Warsa. Disguised as mendicants, they entered the palace to try to persuade the king to stop the wicked ceremony, which was opposed to the teaching of Siva, but they had to take off their coats, as Jara Sanda did not listen to them and became enraged. A war was inevitable. After a fierce battle, Jara Sanda was defeated by the Pandawas.”

|

A scene of Balinese wayang kulit. (Top) Shadow side, (Bottom) Backside. Photographed at Pondok Bamboo Theatre, Ubud, Bali, by M. Iguchi, February 2012. Note that the figures in the shadow are left-right reversed. |

The difference of the Balinese wayang kulit from the Javanese version was not only the feature of puppets and the shape of kayon. The sizes of both the screen and puppets were smaller than those of Java. The motion of puppets was more wild and dynamic and the shadows on the screen were dimly wavering. In the rear, although the manner of the dalang to speak both narrations and words of characters were the same as in Java, he did not pick up puppets himself, but two assistants who sat on both sides handed them one after another. The light source for projection was a coconut-oil lamp, although an auxiliary electric lamp was devised. The gamelan consisted only of two gambang (large brass-made xylophones), played by two musicians, and no singers were there, unlike the full-orchestra gamelan in Java. This scene was virtually the same as was painted in an old picture that I saw in a book[17]. Since the performance was aimed at sightseers, the dalang inserted some ad-libs in English with deliberate Balinese accents. Thus the show finished in one hour in a friendly atmosphere.

|

Wayang kulit puppets of Java (left) and Bali (right), comparison. The character is Bima for both. Images reproduced from: http://tokohwayangpurwa.blogspot.jp. |

Apart from the aforementioned arguments, it was after the foundation of the New Mataram Kingdom by Panembahan Senopati, who unified small kingdoms coexisting after the fall of the Majapahit Kingdom, that wayang kulit was developed into a sophisticated style and moveable arms were invented, and that such characters as Cakil (giant) and his companions were added [18]. After the branching of the royal house into the House of Susuhunan in Solo and the House of Sultan in Yogyakarta in the middle of the 18th century, wayang was cherished in the two royal houses and brought up to the present elegant art. Although it was one side of the history that the division of the kingdom in 1755 AD, arranged by the arbitration of VOC after the three-time Wars of Succession[19], had enhanced the presence of the Dutch in Java, it was undeniable on the other side that kings and nobles were freed from military matters and became able to concentrate on the development of their own art and culture. It was also in the courts of Solo and Yogyakarta that wayang wong (human wayang) mentioned in the earlier part of this chapter was established.

The performance of wayang wong can be seen also in the Pariwisata amphitheatre in the city of Yogyakarta, but the programme is always some extract from the Ramayana that is familiar to sightseers. Although most traditional theatres, which had once existed here and there, were closed with the emergence of cinemas and television, I was informed that one theatre survived in the Sriwedari Amusement Park in the heart of Solo. The one-storey theatre was located in a secluded corner of the park, behind the old-fashioned gilded roundabout and an arena of children’s electric cars powered by electricity taken from the ceiling by a pole. In front of the ticket office, there were signboards for announcing the programme, “Today is Citrawangi” and “Tomorrow is Tunjungsari”. On the stage in the theatre, there was a curtain on which a large gunungan (kayon) was dyed and above the curtain hung a drop curtain on which the head of Kala was woven. The floor of gamelan was situated in front of the stage at the lower level. Among the audience, there were a few groups who were apparently visiting foreigners, but others were local fans. Before the scheduled opening time of 8 pm, about half of the seats were full, despite it being a weekday evening.

When the curtain opened, a flat curtain on which the outer wall of a castle was brightly painted appeared in the back of the stage, but there were no stage settings. About ten actors and actresses acting as princes, princesses and nobles in battle costumes emerged. Although their dresses and accessories looked similar to those of Ramayana ballet dancers, which I had seen in the amphitheatres in Prambanan and Yogyakarta, their carriage looked to be slower and more graceful, as if the show was an orthodox stage drama rather than a ballet. Without understanding their speech, I guessed it was the scene of a ceremony held before going to war. The second stage began in a forest with a talk from a female warrior of another clan to monkey troops, with white masks, who were similar to those in the Ramayana story. The third stage was in an open space in another forest where two warriors from the first and the second clans fought furiously with their knives, but the battle ended in a draw. In the fourth stage two female warriors from the two clans had a dialogue in front of the gate of a fortress. In the fifth stage, the two women fought and the one from the first clan was killed, but, after then, the second woman held the body of the opponent on her lap in sorrow, while men and women of both sides were showing their sympathy. Thus the show of one and a half hours ended while I was not able to understand the full context.

|

Wayang wong performance in Sriwedari Theatre, Solo: The first stage of “Citrawangi”. In the low floor in front of the stage was the gamelan orchestra. Photographed by M. Iguchi, May 2009. |

The Citrawangi must be taken from a certain classic story, but no friends of mine were familiar with it. One of them took the trouble to ask his friend in the literature department of Gajah Mada University, but the source was not defined either. For reference, the programmes of the next and previous evenings, Tunjungsari[20] and Srikandi Edan [21] were episodes from the reign of King Kertanegara in the Singasari Dynasty and from the Bharatayuddha, respectively.

The programme of wayang wong when I visited Solo a second time was “Basudewa Karma”. Since I had no information beforehand, I could not understand the story once again as on the previous time. After returning home, I found an abstract [22] and learnt, with reference also to the pictures taken at the theatre, that it was a story of Prince Basudewa of Madura who fought with rivals and eventually got married to Princess Dewi Badrahini, a daughter of Prabu Badrawinata. It was probably not only me who wished the theatre would have provided an English brochure, even a simple one, in which the abstract was given for visitors who were unfamiliar with Javanese.

One of the features of wayang wong in comparison with Japanese Kabuki and European stage plays was that no stage settings were used and they were painted on the background curtain whenever necessary.

While it is impossible for commoners to see a wayang wong performance held in royal courts, the Marquis Tokugawa was invited in 1929 to the palaces of both Yogyakarta and Solo and left a report on the play and the atmosphere in his Journeys to Java as follows [23]:

“Two pairs of actors appeared on the stage from the left and the right sides, hanging their heads down. There were no sounds in the huge hall and a solemn air filled the space, giving me a sober feeling. The calm was broken, when the king ordered, ‘Start!’ The dalang replied, ‘Oh!’, slowly opened the book and began to read the text. The story was a chapter of Ramayana. Then, the music started and the singer sang. (Yogyakarta.)”

“When the tone of the gamelan changed, two young men with gorgeous clothes stepped gently into view from the far end of the corridor. One could be assumed to be about twenty-one or two and the other, seventeen or eighteen years of age. After they prayed for a while sitting on the floor, pressing their hands and hanging their heads, they raised their heads and stood up slowly with the music to start to dance. They each put a gold bird-shaped helmet on their heads, gold armour similar to the wings of butterfly on the backs of their half-naked upper bodies and a keris with numerous inlaid gem-stones which shone brightly under the light. I was impressed not so much by the beauty of their costume but by the appearance of these young men who looked so noble and handsome. The eye-shadow at the corner of their eyes added accent to their beauty. In front of the dazzling brilliance of the young men, even those female dancers who overshadowed ‘the three-thousands maids serving in the court’ [24] must be eclipsed, just as stars were against the moon. I watched quite absorbed, like a man who had lost his soul, in such a way as my face must have looked odd to other people. When I came to myself, the prince in the adjacent seat tapped on my shoulder, and told me, ‘They are my brother and son.’ I had thought they were not common people and, in fact, they were princes. What splendour! The two princes performed a brilliant dance. It was elegant and tender, but it turned to be fearsome, when the scene moved to a battle-field, as the two bodies crossed and the edges of their keris hit and sparkled. The gracefulness was not lost, however, during such actions. The performance ended after the highlight scene and the two young princes retired quietly after giving a round of salutes. (Solo.)”

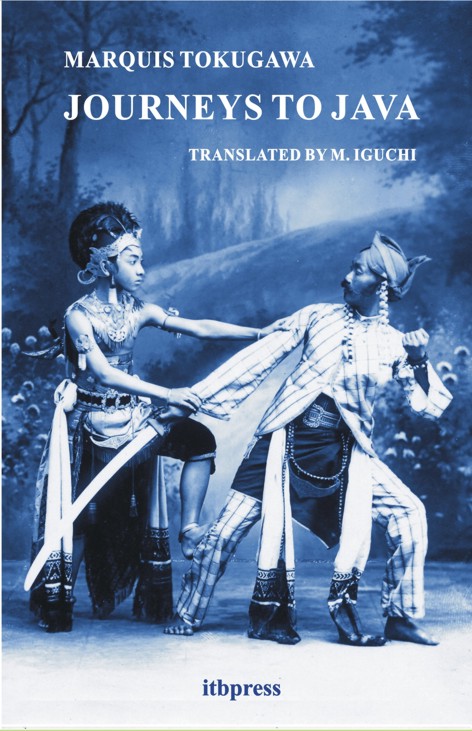

|

Wayang wong in the royal court of Solo. This is one of the photographs presented by Susuhunan X to Marquis Tokugawa when the latter visited Solo in 1929. The same photograph was adopted for the cover of Marquis Tokugawa, (translated by M. Iguchi), Journeys to Java, ITB Press, Bandung 2004. By courtesy of the Owari-Tokugawa Family. |

It is said that the most lofty and sacred of all court dances are serimpi and budoyo danced by female dancers, exclusively maiden daughters of noble bloodlines, the performance of which was only limited at least until recently without being exposed to the public. I had once had a chance to see the dance of serimpi at a dinner show in a hotel in Yogyakarta, but it was a short demonstration version of only some fifteen minutes by two dancers. Since my memory is quite vague, let me again borrow paragraphs from Marquis Tokugawa’s Journeys to Java.

“Before long, the sound of gamelan echoed from a distance. An elderly woman came in on her knees from a door and four dancers followed wiggling their bodies. Their graceful step was the same as that of noh. A prince said it was Serimpi. The dancers’ figures were neat, each wearing a gold crown garnished with fragrant flowers, a silk strip wrapped around their half-naked upper-body up to the level of their breasts, a trailing batik skirt, a coloured gobelin on their waists, and nothing on their bare feet. Then, some other elderly ladies who played the role of prompters came behind on their knees. There was a slim table in the centre of the four pillars on which four cut-glass bottles filled with a red liquid and four cups of the same design were placed. The dancers entered the central area, separated at the four corners and pressed their hands together while sitting on the floor. They then stood up slowly to dance quietly and silently.

“The night at the royal palace in the country of perennial summer was cool and serene, as if it were the limpid autumn in our own country.

“The graceful dancers danced by waving their light clothes, and moving closely, or separately of each other under the Dutch lanterns, like butterflies fluttering around flowers. The dance turned into a duet and then into a solo. One of the dancers gently took up a cup and her partner poured the red liquid in it. She danced for a while holding up the cup and then gulped down the liquid.

“The dance was still quiet. Suddenly, the dancers took up pistols from their waists and, after stepping around, raised the cock and fired all at once, making most of the guests quite astonished. They continued the dance quietly, however. Serimpi was over in about an hour. Then, Boedojo danced by nine dancers were shown. The performance was similar to Serimpi, but, on that occasion, nobody was startled by a simultaneous firing as everyone had been expecting this…”

It was pointed out in a book that “the Javanese theatre embodies spiritual and cultural values of deep significance; only the No‑gaku of Japan can be compared with it, and even so the Javanese has a wider range of theme and is far more than an exquisite survival.”[25] Noh or Noh-gaku established by Ze-ami Motokiyo (1363?–1443?) during the era of Shogun Yoshimitsu Ashikaga in the early Muromachi Period was protected during the Yedo Period by Shogun and other clans as ceremonial play of warriors and performed on special occasions in their houses. If I was to supplement, Ga-gaku promoted in the Imperial court since ancient time could belong to the same category.

The theatre of wayang kulit had generated various derivatives to form the so-called “wayang world”, the word, wayang, which literally meant “shadow”, having been applied to various plays other than wayang kulit. Wayang kulit itself, which traditionally played such classic stories as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana that are now called “wayang purwa” (lit. original wayang), had been applied in the 15th–16th centuries in East Java to perform the Panji Stories[26] and Damar Wulan Legend [27], classified as “wayang gedog”, and in the court of New Mataram a new repertory called “wayang madya” to play episodes of former kings, viz. King Jayabaya of Kediri, was added. In addition, wayang kulit based on the history of Yogyakarta (Wayang kuluk) and that of Solo (Wayang dupara, see the illustration of the back cover of this book/a photograph in Chaptr 1) were created. The activities of Prince Diponegoro, the hero of the Java War (1825–30) was made into Wayang Jawa. Wayang to play such a fable as “mouse and deer” was also born, as I actually saw several pieces of animal puppets in the Yoshichika Southeast Asia Collection (not open to the public) in the storehouse of the Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya, Japan. In the later centuries, wayang was further used for the teaching of the Catholic religion. After the independence of the Republic of Indonesia, it was applied for the spreading of Pancasila (the state ideology), although it was not very successful. Nevertheless, wayang purwa is still beloved by Javanese people, while those new wayang kulit have almost diminished.

|

A set of Wayang Katolik puppets (left) and a magnified image of Jesus (right). Owned by Pangudi Luhur Primary School, Surakarta. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012. According to the schoolmaster, Br. Aloysius Istiyanto, FIC, Wayang Catholic, formally called Wayang wahyu (wahyu=revelation) is played in the Christmas and the Easter seasons. |

“Wayang kelitik” or “wayang kerucil” was a kind in which the design of puppets was similar to that of wayang kulit but the bodies were made of wood board and colourfully painted. Although puppets were manipulated by holding the main axis and moveable arms, this wayang was not aimed at casting a shadow but showing the substance itself [28], at least in its beginning, contrary to the description in Internet articles or even in books[29]. Recently, old 16 mm movie films filmed in the 1920s in Java by Marquis Tokugawa have been discovered in a corner of the Tokugawa Art Museum’s storehouse [30], and I was given a chance to watch them courtesy of the Marquis’s great-grandson. In the shot of wayang kelitik in it, probably taken in Yogyakarta, there was no screen to project shadows in front of the puppeteer. Anyhow, wayang kelitik is no longer played today.

|

Puppets of Wayang kelitik (from Yoshichika Southeast Asia Collection). By courtesy of the Tokugawa Art Museum. |

One more wayang played with puppets is “wayang golek” in which three-dimensional figures are employed. The structure of puppets is composed of a wooden cylindrical body, in the centre of which is passed an axis to turn the head fixed on its top, and two arms that hang down from the shoulders are moveable by narrow rods like those of the wayang kulit puppets. The upper and lower parts of the body are dressed with batik-made kubaya (blouse) and sarong (skirt), respectively. Although the origin of wayang golek is not sure, it is said that a prototype arrived from China was first adopted to play Menak Stories [31] in the Islamised towns on the north coast of Java in the 17th century and the repertory was expanded to cover the Ramayana and other classic titles. Wayang golek became popular particularly in West Java and stories of such heroes as Mur Jangkung (Jan Pieterszoon Coen) and King Siliwangi were added in its repertory as mentioned in the Jagatara Tales (See Chapter 2). Although the puppets of wayang golek are abundantly sold as souvenirs in department stores and other shops in Jakarta, Bandung and elsewhere, wayang golek is rarely performed today. I have once seen a short performance of some fifteen minutes demonstrated for tourists in a hotel in Bandung.

|

Puppets of wayang golek (from Yoshichika Southeast Asia Collection) From the patterns of the puppets’ dresses, these are considered to be high-grade pieces from Yogyakarta, not from West Java. Note that the rods to manipulate hands have been removed. By courtesy of the Tokugawa Art Museum. |

Among wayang played by human is a masque called “wayang topeng”, which must be older than wayang wong, as its major titles were the Panji Stories. Up until today, this play has survived in Bali, although I have not had a chance to see it, while it has long been lost in Java, neglected by the courts of Solo and Yogyakarta.

|

Masks for Wayang topeng. Photographed with permission in the Bali Museum, Denpasar, Bali, by M. Iguchi, February 2012. |

There was a different type of wayang called “wayang beber” in which a dalang read a text, while rewinding a picture scroll held upright between two poles. Although some people assume that its origin was older than wayang kulit and dated back to the 4th or the 5th century [32], it is generally agreed that it was after the 12th century when the Panji Stories, the Mahabharata, the Ramayana and other stories were adopted [33]. Wayan beber must have been popular in the Majapahit Period as it was written in The Overall Survey of the Ocean Shores (Ying ya sheng lan , 1416)[34] by Ma Huan (馬歡) who accompanied the great voyage of Zheng-He (鄭和) in the Ming Period China, but it had gradually declined in the later time and we could only see the scene of its performance in photographs taken in the early 20th century. The sheet used for the picture scroll was a bark-sheet called “daluang” prepared by elaborately hammering the white inner-bark of paper-mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera), which was used also for books ( See Chapter 4), but not as much as lontar. While daluang as well as lontar were obsolete after the introduction of pulp paper and its manufacturing technology, I had recently learnt that some efforts to try to reproduce daluang were made today in an exhibition held in the Paper Museum, Asukayama, Tokyo, in which a video film of its manufacturing process, a picture of wayang beber traced on a trial sheet and some other related items were displayed [35].

|

A scene of wayang beber performance. Reproduced from: W. F. Stutterheim, Pictorial history of civilization in Java. Translated by Mrs. A. C. Winter‑Keen, Java Institute and G. Kolff, 1927. |

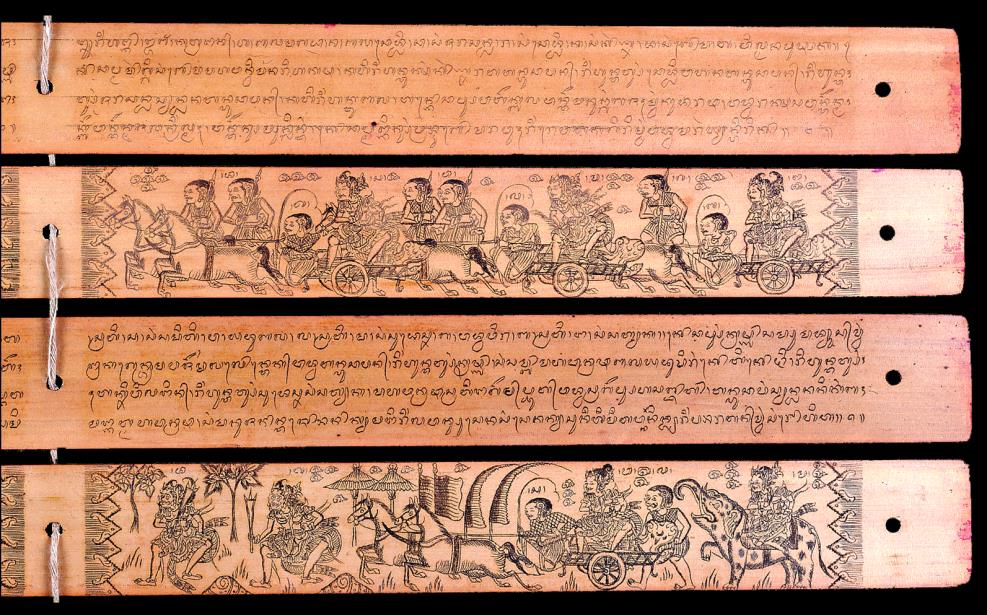

It may be better classified into the category of a picture book rather than that of wayang, but there were lontar documents in which not only the text but also illustrations of a story were inscribed, as we often see some pieces in museums. As mentioned in Chapter 3, lontar itself was a leaf of lontar or siwalan palm (Borassus flabellifer), cooked in water containing turmeric as an antiseptic, cut into a strip, and pressed, on which letters and/or pictures were inscribed and filled with a compound of soot and oil; the strips were bunched like a Venetian shade. An antique piece that I obtained in the courtyard of Bali National Museum in Denpasar from a pedlar was a souvenir article probably produced in the early last century. Although he said it was prepared by the traditional method, the set consisted only of eight leaves, on each of which were engraved a scene of Ramayana in the middle and a short Javanese or Balinese text and its English translation on the left and right sides, respectively. It is hard to imagine how ancient workmen persevered to make a copy of one complete book of long kakawin that needed several hundred or more leaves. Just for reference, the young fruits of siwalan palm are edible and nice, the texture and taste of which being more of less similar to lychee.

|

Lontar of Kakawin Bhomakawya (Bhomantaka) held in the National Museum, Jakarta. A part of image obtained by courtesy of The Lontar Foundation (Jakarta). |

Here let us review the history of Javanese dynasties after the capital of the Old Mataram Kingdom, which had built magnificent Borobudur and Prambanan temples, was transferred to East Java in the 10th century, until it was moved back to Central Java where brilliant flowers of Javanese culture bloomed after the 16th century.

It was in 929 AD that King Mpu Sindok of the Sanjaya Kingdom moved the capital to Medan on the bank of Brantas River (around the present-day Jombang) from the land of Mataram and opened the Isyana Dynasty. The direct cause of the transfer was probably the devastation of the old area by the great eruption of Mt. Merapi, while such other issues as political turmoil, troubles with fanatic Buddhists and the exhaustion of resources for constructing monuments were also conjectured as other reasons (See Chapter 5). The new dynasty had gathered strength in the new ground to such an extent that enabled them to campaign to Sriwijaya in Sumatra. According to some old records, a great-granddaughter of King Sindok, Princess Mahendradatta, married Prince Udayana of the Warmadewa Family in Bali and in 990 AD gave birth to Airlangga who was to become a great king in Java. In 1006 AD, when Airlangga was visiting his mother’s house in Medan to be betrothed to Princess Dyah Sri Laksmi, the daughter of his uncle, King Dharmawangsa Tegu, the castle was burnt down, attacked by the army of Sriwijaya, and the king was slain [36]. Airlangga fled to a forest for safety with the princess and remained there for some ten years until 1019 AD when he finally took up arms to unify the country, which had been torn after the death of his father-in-law, and assumed the crown by the request of the family. Thus the connection between Java and Bali became closer.

In 1037 AD, Airlangga moved the capital to Kahuripan (or Kediri) and founded a new kingdom. Being blessed with peace, thanks to the weakening of Sriwijaya caused by the attack of Chola, India, the enhancement of rice production by the introduction of irrigation systems and the opening of trade routes to India and China enriched his country, and such measures as the demolishing of slavery and the establishing of legislative system brought happiness to his subjects.

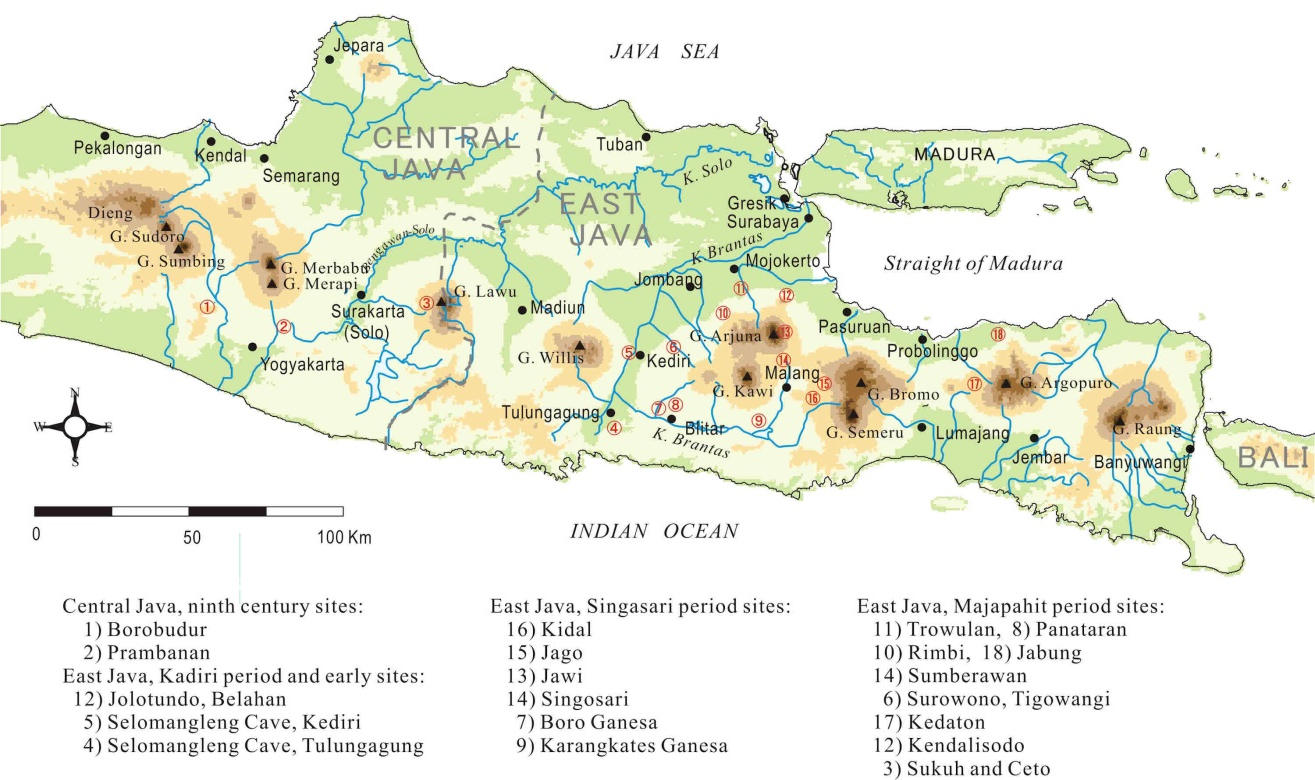

|

Historical sites in Central and East Java. Map prepared by DIVA-GIS/Country Level Data. Abbrs: G (Gunung)=Mountain, K (Kali)=River, C (Candi)=Temple. Location data from Ann R. Kinney, Marijke J. Klokke, Lydia Kieven, Worshiping Siva and Buddha: The temple art of East Java, University of Hawaii Press, 2003. |

Arjunawiwaha, a paean to King Airlangga

King Airlangga also paid much attention to art and culture. While the translation of the Mahabharata into Javanese was said to have been achieved during the time of his father-in-law, Dharmawangsa Tegu, “Arjunawiwaha” (Arjuna’s marriage), reputed as one of the most beautiful pieces of work among numerous kakawin, was authored during Airlangga’s reign in 1035 by Mpu Kanwa, his court poet. The story [37] is very shortly as follows.

“Arjuna was ordered by the gods to defeat Niwatakawaca, the demonic king of titans, who had threatened to destroy the heavenly world. As a ksatria [warrior][38], he discovered the weak point of the demon king, the tip of his tongue, with the help of Nymph Supraba for whom the demon king was passionate, and finally killed the foe, who had advanced to the heaven, in a fierce battle. Arjuna was made the king for the period of seven months (i.e. seven days on the earth) and enjoyed a happy time with Supraba and six other nymphs, until he returned to the earth.”

This story includes such scenes that “Arjuna who had retired in a grotto of Mt. Indrakila was subjected to the temptation of beautiful celestial nymphs who were despatched by gods to test Arjuna’s steadfastness”, that “Arjuna duelled with God Siva who was in a disguise of a hunter, when their arrows shot simultaneously against a boar, which was the incarnation of Giant Murka sent by Niwatakawatja, merged into a single arrow, and both of them claimed the merit”, etc, which are quite amusing to an audience. This poem is said to be a paean to Airlangga in which his life was overlapped with a part of the Mahabharata[39] .

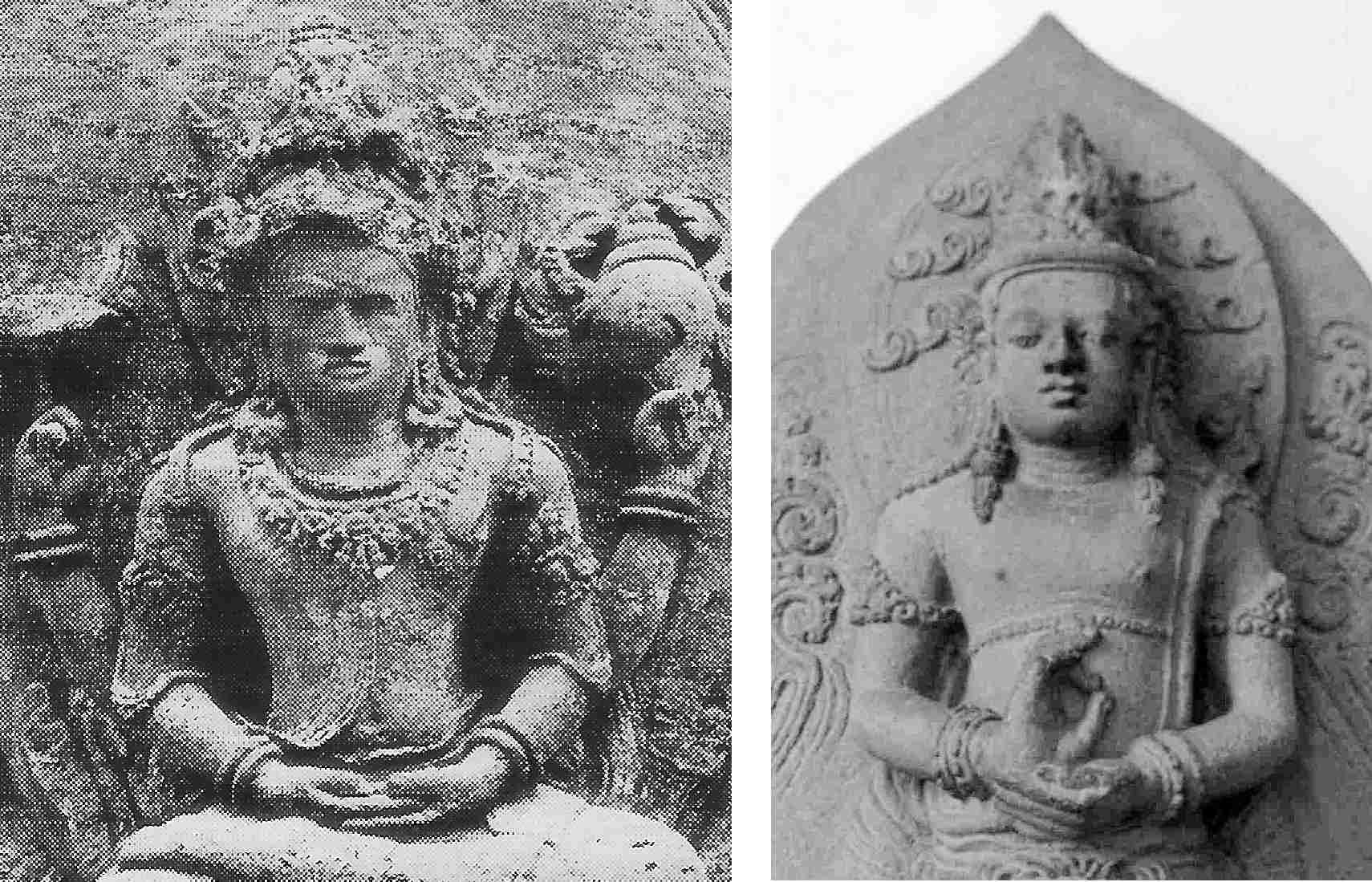

Candi Belahan on the slope of Mt. Penanggungan is said to have been built as a memorial of Airlangga in 1049. I have seen the principal stone statue removed from the candi to the Trowulan Museum. Airlangga who was deified as the incarnation of God Visnu was mounted on Garuda, the vehicle of Visnu, with his hands in meditation mudra, emitting a saint-like aura. Another statue (standing statue) of Airlangga found in Singasari is now held in the National Museum in Jakarta. Although the second statue was said to have represented God Siva[40], the expression of the god with his hands held in the mudra of auspiciousness-of-wisdom looked to me rather gentle as that of a Buddha, unlike that in the Hindu temple of Lolo Jonggrang in Prambanan, which bore a rather hard look. This can be evidence to attest that Airlangga, who was generally regarded as a Vishnuist, was paying attention also to Shivaists, although this is a mere view of an amateur as myself.

|

Upper bodies of two Airlangga statues. Left: Airlangga riding Garuda as the incarnation of Vishnu (Trowulan Museum), reproduced from Ann R. Kinney, Marijke J. Klokke, Lydia Kieven, Worshiping Siva and Buddha: The temple art of East Java, University of Hawaii Press, 2003. Right: A standing statue assumed to be the incarnation of Siva (National Museum Indonesia), photographed with permission by M. Iguchi, February 2012. |

The Golden Age of Javanese literature

In 1041 AD, Airlangga divided his kingdom into two parts, the western Panjalu (Kediri) and the eastern Janggala for his two sons and lived in retirement until his death in 1049, but the latter kingdom was not well governed and became stagnant, while the former maintained stability. In my personal view, the division of the kingdom that must be ascribed to Airlangga’s personal consideration was the only one misgovernment of the great king. It was after the beginning of the 12th century when King Sri Jayawarsa of Panjalu reunified the two divided kingdoms and founded the Kediri Dynasty. Thus, prosperity was restored in Java and the golden age of Javan literature started.

During the reign of the third king, Jayabaya (1135–57), poet brothers, Mpu Sedah and Mpu Panuluh, composed the Bharatayuddha, a monument of classic Javan literature, and some other kakawins [41].

Although the Bharatayuddha was an adaptation of the last chapter of the Mahabharata, as mentioned before, homages to the king were added in the beginning and the ending parts [42], and the year of drafting, 1157 AD, was noted.

A contemporary poet, Mpu Triguna composed another famous kakawin, Krsnayana, the abstract of which is as follows:

“When Princess Rukmini of Kundana Kingdom was engaged for political expediency to King Suniti of Cedi, Krsna received a letter from his aunt, Rukmini’s mother, that ‘The only man my daughter ardently loves is no other than you, Krsna. Please, rescue her before it is too late!’ He went to Kundana by chariot with his army, pretending to have appeared as a relative for felicitations and was given accommodation in the outside of the palace. Krsna contacted Rukmini through a maid. Under cover of the darkness, while it was congested with a number of guests, Rukmini successfully escaped out of the palace in the disguise of a nun. Krsna put her on his chariot and ran away. When Rukma, the brother of Rukmini, who chased after them, discovered them in a shelter and accused Krsna’s infamous conduct, Krsna countered that it was a generally accepted custom for a ksatria (warrior) to obtain his bride by force. A battle began and when Rukma finally fell to the ground and lay defenceless, Rukmini seized Krsna by the feet and implored him to spare her brother’s life. Krsna carried his bride off to Dwarawati, where they enjoyed the pleasures of their union in undisturbed peace. Rukmini bore him ten children.”

Krsna is also a popular hero still loved among the Javanese, like Arjuna, as persons who were given these names from parents were among my acquaintances. The statue of Arjuna and Krishna on the chariot located near the Medan Merdeka (Independence Square) in the Jakarta city cenre has been introduced in Chapter 2.

The Smaradahana and the Bhomantaka

During the reign of King Kameswara (1182 or 1185–94), “Smaradahana” was authored by Mpu Dharmajan. The kakawin sang a tale that:

“When the God of Love, Kama was burnt by God Siva in the Heavenly World, Goddess Ratih jumped into the fire according to the custom of suttee [also spelled as ‘sati’]: both of them fell to Earth and revived as human”, with an epilogue that the couple was no one else but King Kameswara and the Queen Kirana.[43] It is said that Smaradahana was the precursor of the Panji Stories, which spread not only in Indonesia but also in Malaya and Thailand [44].

Bhomantaka, a kakawin composed by an unknown poet and dedicated to an anonymous patron, some phrases of which were cited earlier, is believed to have been produced in the same Kediri Period. Although this long poem, which sang the tragic death of Bhoma who fought with Krsna, is no longer performed in wayang kulit and other theatre, its literary quality is pretty high, being favourably compared with the Iliad, Hamlet and Faust, and the lofty intellect of the composer is manifested throughout the 1,942 stanzas. In the first canto, for instance, it was solemnly sung[45]:

|

In truth “the Chief judge in Poetical Affairs” is he who embodies beauty in himself as an incarnation of the God of Love. Let him be worshipped with flowers, seated in the lotus, and let the secrets of the Book of Love be unfolded. Let his temple be built of poetic language thus, and be made a worthy place for the deity of amorous longing to be given a visible form, For in the invisible world Anangga (the Bodiless) is what he is called by the musing poet who is an expert in allegorical narrative. |

While an ancient temple in Java, called candi, was usually a stone structure that was aimed at worshipping ancestors and inviting gods as entities, I could not but esteem the poet’s high-mind “to build a temple of poetic language”.

One may remember that the time when such fine literature flourished in the Medan-Kediri Period Java (929–1222) coincides with the middle and the late period of Heian Era (ca. 930–1192) in Japan when The Story of Genji, Makura-no-Soushi (The Pillow Book) and various novels and essays appeared.

Around the present city of Kediri, there remains almost no monuments of the ancient kingdom, whether candi and other solid structures were buried under the ground or they had actually not been constructed, the only exception that I saw during my visit being the site called Tirta Kamandanu that was said to have been the bathing place of King Jayabaya. There was a stone gate that resembled a castle gate and on the left-hand side of it was a stone statue of some divinity, about three metres tall. Later I learnt it was a Hindu god called Harihara who had the divinities of both Visnu (Hari) and Siva (Hara). I thought that such a god that could be worshipped by both Visnuists and Shivaists was necessary in ancient Kediri where the two denominations coexisted. In the opposite side of Harihara was a carving of Ganesha[46] set back to back to the former. In the lower ground behind the gate, there was a stone-framed pool of a complex shape in which waterweeds grew over the water surface. For me, it was hard to imagine a scene in which a sacred king bathed.

|

A front view of Tirta Kamandanu, allegedly the bathing place of King Jayabaya. A statue of Harihara and a gate are seen on the left- and right-hand sides. Photographed by M. Iguchi, May 2009. |

In the suburb of the city, there was the graveyard of King Jayabaya called Petilasan. In the shrine enclosed with stone pillars was an objet d’art of an eyeball, which symbolised the penetrative power of the king, and in a corner of the ground some five metres away from the edge of the shrine’s precinct was a simple headstone. The graveyard constructed in the 1970s on the spot where the king had allegedly been buried gave no solemn atmosphere to me. Probably, King Jayabaya is well known by the so-called “Jayabaya Prophecies” especially in Japan ( See the appendix of this chapter to which the present writer’s comments are added).

The appearance of a hero, Ken Arok

The kingdom of Kediri, recorded inRepresentative answers [about the region] beyond mountains (Lingwai daida, 嶺外代答) by Zhou Qufei (周去非) [47] in Southern Sung Dynasty China as “Java is the second richest among foreign countries next to Tajik [Saracen]”, began to decline after the turn of the 13th century. The last king Kertajaya (1185–1222) was a tyrannical and brutal man who was hostile to religious leaders. Tunggal Ametung, the local magistrate of Tumapel, the former capital of Janggala, was also an oppressive man who persecuted unfavourable monks and imposed heavy taxes on peasants. The hero appearing in such a situation was Ken Arok (or Amrok) who came from sudra, the lowest caste, and became the founder of Singasari Dynasty. His life written in the early half of Pararaton [48], a history book composed in the later century, was briefly as follows:

“Ken Arok was born to a farmer’s wife, Ken Endok, who was impregnated by Brahma. He was abandoned soon after his birth but was found, as his body emitted light, and brought up by a robber named Lembong. Having been adopted by a gambler named Bano Samparan, he spent all his time thieving, gambling and raping, and occasionally committed murder. Once, he escaped from pursuers by flying away on a leaf of fan palm according to the heavenly voice. In such a life, he learnt, one period, reading, writing and arithmetic as well as the calendar, science and literature from Jangan (a knowledgeable village man). When Arok was wandering, guided by god, he met a high priest of Sivaism named Sang Hyang Lohgawe who had sailed from India by sea, standing on three pieces of bindweed leaves. Arok went to Tumapel together with Lohgawe to serve for Tunggal Ametung. One day he saw the secret part of Ken Dedes, the daughter of a Buddhist priest, Mpu Purva, who had been kidnapped by Tunggal Ametung and made his wife, illuminate, when she descended from her coach. Having been taught by Lohgawe that such a woman would bring fortune to a man [49], Arok determined in his mind to obtain her. He ordered a keris (sword) from a swordsmith named Gandrin and, when it was unfinished on the day of promise, he angrily stabbed Gandrin with that keris. At the last moment, Gandrin said, ‘You shall be stabbed by this keris, and your son, grandson and offsprings, seven all together, will be also killed in the same method.’ Arok gave the keris to his fellow soldier, Kebo Hijo, and one night he stole it and assassinated Tunggal Ametung. The guilt was put on Kebo Hijo, as Arok plotted. Arok who made Dedes his wife became the king under the name of Sri Rajasa Bhattara Sang Amurva-bhumi, founded the Singasari Kingdom, and finally ruled the whole of East Java from 1222 AD after defeating Daha (Kediri), which had dominated over Tumapel.” [50]

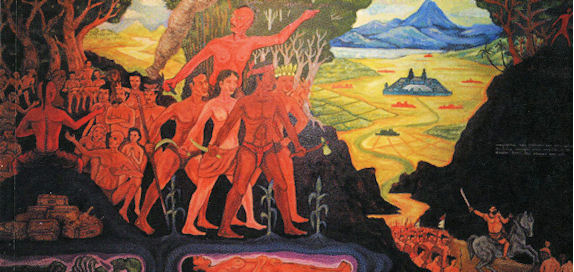

|

The cover illustration of Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s novel, “Arok of Java”, (Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Arok of Java: a novel of early Indonesia, Horizon Books 2007) in which Arok is commanding a rebellion. Reproduced by courtesy of the publisher. 10 |

Whilst the Pararaton was composed of plain records of historical facts with the insertions of God’s dispensations, Arok of Java [51], a historical novel by the great writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer, was quite useful for me to envisage the personalities of characters and the historical background, although the details of the story were different in some parts. For instance, Arok was depicted as a rare genius who had mastered the whole phrases of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana and spoke beautiful Sanskrit, and who notwithstanding his outrageous character always sided with the weak, like Robin Hood in English folklore, and the psychological state of Dedes in changing circumstances was realistically described. Also, the book of Pramoedya provided knowledge about the religious situation in the contemporary Java, viz. the struggle among Shivaists, Visnuists, Mahayana Buddhists and Tantrists, which was not available in textbooks. According to Pramoedya, what Arok aimed at was a society in which believers of different religions were harmonised.

In addition to three sons and one daughter begot from Dedes and another three sons and one daughter from his second wife Umang, Arok had a son-in-law named Anusapati, Tunggal Ametung’s posthumous child who was in the womb of Dedes before Arok obtained her. Although Arok’s wise governance went on for twenty-five years, he was killed in 1247 AD by Anusapati who grew up and became aware of the secret of his birth with the Gandrin’s keris, as cursed by the swordsmith. After then, the assassinations of kings were repeated. Anusapati who succeeded Arok was killed by Tohjaya, a son of Umang who noticed the cause of his father’s death. Tohjaya became the king, but died for the wound given by Rangawuni, Anusapati’s son. In all cases, the weapon was the same keris of Gandrin.

The Mongolian invasion and the founding of Majapahit

During the reign of the 5th king, Kertanegara (a son of Rangawuni), who was in power for twenty-four years from 1268, Singasari expanded its hegemony over Sumatra and conquered Bali, but, in the later period, the country met a mishap, i.e. the Yuan Expeditions, as some other Asian countries also did around the same years, e.g. Japan in the Kamakura Period [52]. When Khubilai Khan sent embassies and demanded allegiance in 1280, 1281 and 1289, Kertanegara rejected the demand every time and, on the third occasion, sent the mission off after injuring the diplomats’ faces. In anger, Khubilai sent a huge force with a fleet of 1,000 junks in 1292, but prior to their arrival in November, Kertanegara had been killed in May of the same year in the coup d’etat led by Lord Jayakatwang of Kediri under the control of Singasari, allegedly a descendant of the noble of the former Kediri Kingdom, who had wished to restore his ancestor’s kingdom. Thus, Singasari was already extinct and Tumapel was in the hand of Jayakatwang. The person who met the Mongolians who came to the port of Tuban was Raden Wijaya, a noble of Singasari, who had pretended to be royal to Jayakatwang and obtained a fief in the northern area of Mt. Arjuna (i.e. to be Majapahit, the present-day Trowulan). In alliance with the Mongolian army, Wijaya attacked Tumapel and captured Jayakatwang. When the Mongolian demanded to hand over two princesses of Tumapel (Kertanegara’s daughters), who were in the custody of Wijaya, for a souvenir for Khubilai, Wijaya told them to come to his castle. As soon as the Mongolian soldiers entered the palace, Wijaya’s men shut both front and back doors and assaulted the enemy. They chased the Mongolians who managed to run to their camp or ships in the harbour and killed all of them[53].

An episode has it that tahu (beancurd), one of the most popular foods in present-day Indonesia, is said to have been introduced at that time from China[54].

Raden Wijaya founded the Majapahit Kingdom in November 1293. He was a son-in-law of the late Kertanegara, but what was more important was the fact that he was the great-grandson of Ken Arok and Ken Dedes, the bloodline continuing to the present royal families of Solo and Yogyakarta, being esteemed as the most precious one in Java. When I asked my friend descended from the Yogyakarta family, “Are you conscious in your life that Ken Arok and Ken Dedes are your ancestors?” she replied, “No, only as historical persons,” however.

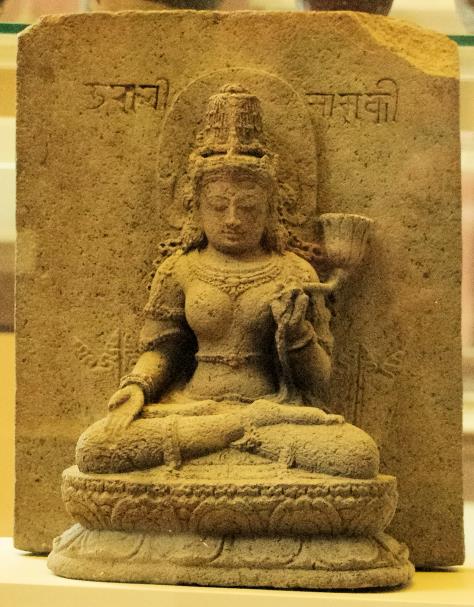

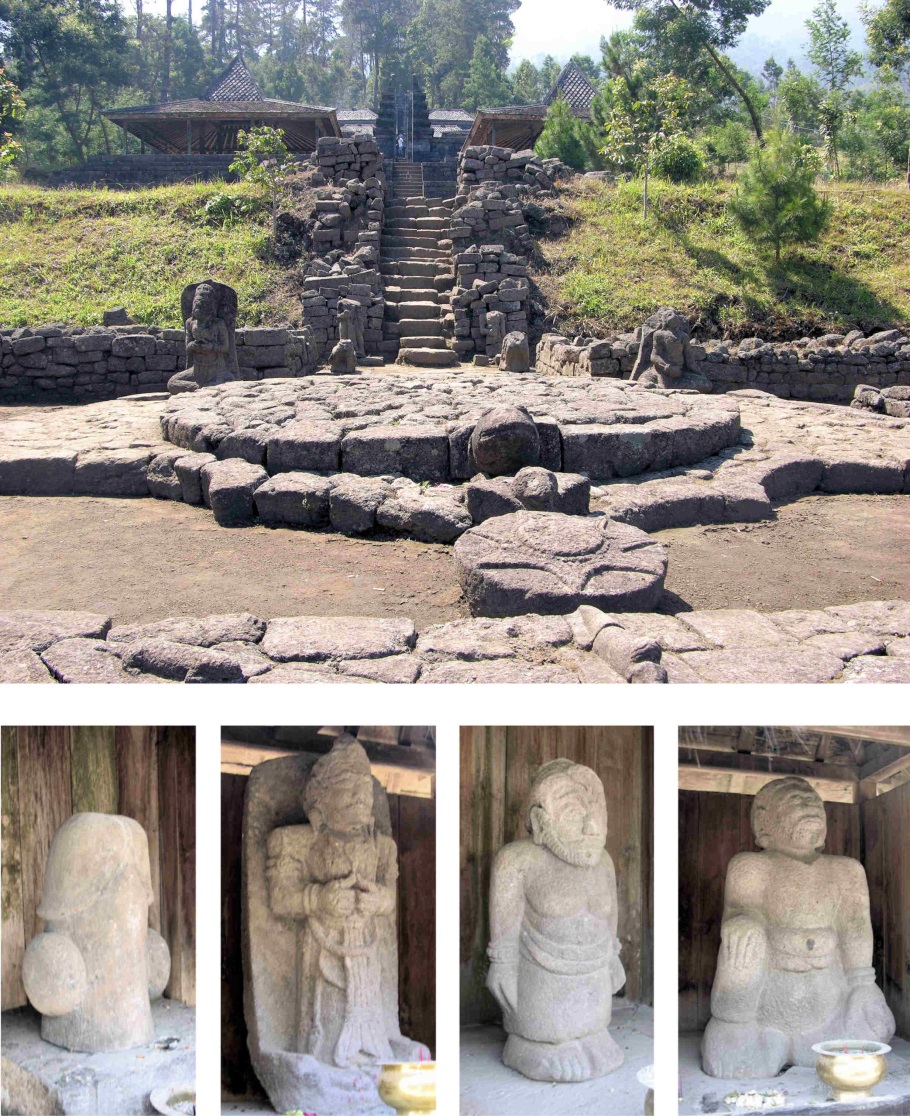

The remains of Singasari, the statue of Prajnaparamita

Some monuments of the Singasari Period remain in the vicinity of the present-day Malang city, the central part being assumed to have been the area called the Singasari Complex, which is supposed to have comprised, besides Candi Singosari for enshrining King Kertanegara, some Buddhist temples, some Tantrist buildings and other constructions. A pair of stone statues of raksasa, which guarded the area, were so large that I was quite startled when I visited there a decade ago for the first time. At the two-storeyed Candi Singosari restored in 1936, two heads of Kala, placed one each on the front of the two floors, looked different in terms of the level of carving work, the upper one having been well finished, but the lower one not. Also, the top part of the temple lacked a pyramidal roof. It is said that this candi was never finished due to the abrupt end of King Kertanegara’s reign[55].

|

A pair of huge raksasa statues of dwarapala (gate guardians) of the Singasari Period. One is seen in the distance. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2002. |

|

Candi Singosari (left) and two Kala’s heads (right) Note that the Kala’s head at right-bottom is unfinished (See, the first paragraph under the section title: “The remains of Singasari, the statue of Prajnaparamita”). Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2010. |

Among several sculptures unearthed from this temple complex, the best piece must be the statue of Prajnaparamita, modelled after Ken Dedes, which can be seen in a special exhibition room in the National Museum in Jakarta. A daughter of the high Buddhist priest, Ken Dedes was a Buddhist. I believe that the anonymous carver who worked on this statue must have devoted his deep faith to the Buddhist saint as well as his sincere respect to Queen Dedes, a reputed perfect beauty practising in pursuit of perfect wisdom with her hands signing the mudra of the auspiciousness-of-wisdom, by superposing her image on that of Kwannon, the Goddess of Mercy [56]. This statue, the honour and distinction of which is said to have been exalted in recent exhibitions in Europe, leads a spectator to the illusion of Ken Dedes having had eternal life. There is no doubt that Ken Arok had an ambition to obtain her for himself. In front of the statue, I thought no man in the world could not but be charmed by this lady. The later life of Ken Dedes after the loss of her husband Ken Arok is unknown as long as I have surveyed literature. I supposed, “Had not she her hair shaved and did she live in a Buddhist nunnery, instead of following the custom of suttee [the self-immolation of Hindu women after their husbands’ deaths]?”

|

Upper body of the statue of Prajnaparamita, modelled after Ken Dedes. Photographed with special permission by M. Iguchi, February 2012. |

Where was the legendary mausoleum of Ken Arok called Kagenengan located? Although Desawarnana (alias Nagarakertagama) recorded that a fine candi stood in a sanctuary surrounded by a wall with a gate to the south of Singasari[57], the location is not determined today. The caretaker of Candi Singasari told me that there was a possible site at the foot of Mt. Kawi, but I gave up visiting there because it was said to be very far.

About two kilometres away from the Singosari Complex, there was a rectangular pool of about 6 × 20 metres, called Petirtaan Watugede, in the ground below the near-by road, shaded by tree leaves. It was an old pool, which was said to have existed ever since the era of Ken Arok, and Ken Dedes had bathed there. It was still full of clean spring water.

| Petirtaan Watugede. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2010. |

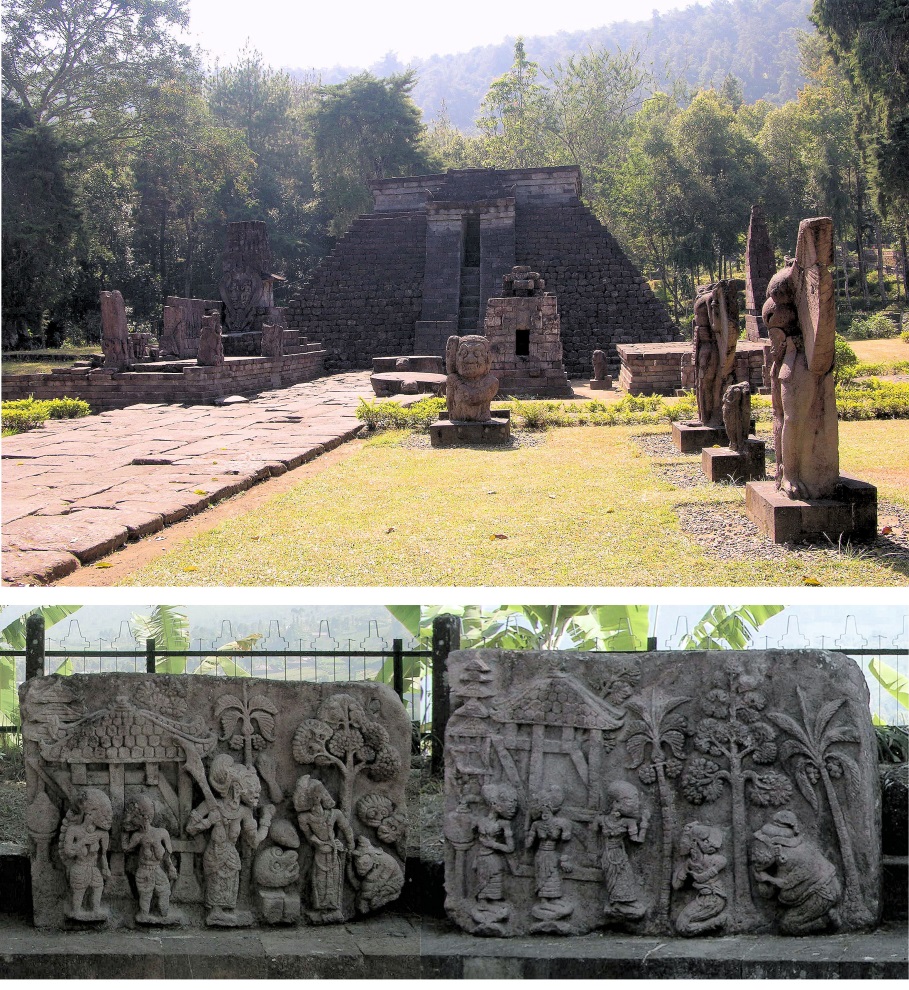

Candis in the vicinity of Malang

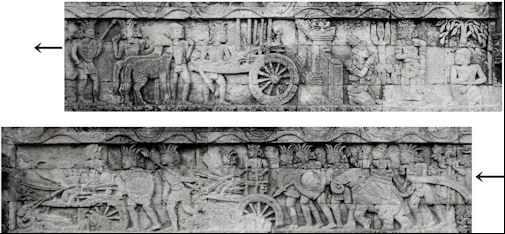

In the vicinity of Malang, there remained two candis, Candi Kidal and Candi Jago, dedicated to King Anusapati and King Wisnuwardhana, respectively, and on a hillside in the suburb of the city was Candi Sumbrawan, the only pure Buddhist stupa remaining to date. Among them, the most attractive to me was Candi Jago. Although the main building was only half-restored and sculptures of Amogapasa[58] and the head of Kala were left on the ground of the precinct, the walls of the basement and the upper stairs of the building as well as of the flights between them were decorated all over with various reliefs. When I first visited there, I had thought the carvings with flattened figures were inferior to those true-to-life three-dimensional figures in the temples of the Old Mataram Period, namely Candi Prambanan, and put that impression in my memo, but it was a grave misunderstanding due to lack of knowledge. Later, I read[59] that the scenes of some stories were depicted as if they were in wayang kulit puppet shows. Also I learnt that the existing candi was regarded to be a new construction or reconstruction in the mid-14th-century Majapahit period, judging from the feature of the style of relief and the structure of the building itself. It was a pity that I could not take good photographs, even when I revisited there with a new camera, because the carvings were badly eroded from weathering. The stories in the relief were various and included the Hindu Arjunawiwaha, Krsnayana and Parthayajn [60] and the Buddhist Kunjarakarna[61] and Tantric tales, suggesting the coexistence of the various religions at that time.

|

Candi Jago, a part of the second stage and the ruin of the third stage. The relief shows a scene in the Mahabharata, the journey of Arjuna to Mt. Indrakila. Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2010. |

|

Candi Sumbrawan (left) and Candi Kidal (right). Photographed by M. Iguchi, June 2010. |

Whilst most of the statues existed in these candis have been reposited in the National Museum, Jakarta, some pieces collected in early times before the Dutch government prohibited the export of historical arts and crafts in the late 19th century are scattered in the world. In the British Museum, I was impressed to see a statue of Goddess Mamaki of ca. 45 cm height, labelled as collected from Candi Jago [62], preserved in an intact condition. Her left hand held a lotus and her right hand was showing a gesture of dispensing of boons(varadamudra). Among some other sculptures from East Java was a statue of Ganesha, labelled as a work of the 12th century, although the place of its origin was not shown.[63]

|

Left: A statue of Mamaki of 13th to 14th centuries AD from Candi Jago,

East Java, acquired in 1859 in the British Museum. |

As mentioned above, the Majapahit Kingdom founded in 1293 had its heyday during the reign of Hayam Wuruk, crowned under the name of Rajasanegara (1350–89), when the power extended from Java Island (excluding the west part where the Pajajaran Kingdom existed) not only to Sumatra, Kalimantan (Borneo), Sulawesi (Celebes), Bali and eastern islands, which were to be covered in territory of the present-day Indonesia, but also to the Malay Peninsula. The source of the wealth of the kingdom was agriculture, and the richness was written in An Account on Foreign Countries (島夷誌略, Dao Yi Zhi Lue) written in c. 1330 in China, as:

“The rice field is fertile, irrigated by abundant water, and the productivity of rice is twice that of others. People never steal and never pick up anything dropped on the roads. That is why it is called ‘Pacific Java’.”[64]

In his book[65], Odoric of Pordenone, a contemporary Italian who travelled to the Middle East, India, East Indies and China introduced Java as, “The king has seven dependencies. The island is exceedingly populous and is the second best of all islands, as it grows camphor, cubebs, cardamoms, nutmegs, and many other precious spices…”, wrote, “The palace was truly marvellous, as the wall and staircases are plated with gold and silver, the pavement is tiled with gold, figures of knights are sculptured on the wall, the ceiling is all of pure gold, etc. This palace is richer and finer than any existing one in the world”, and concluded, “The Great Khan of Cathay [China] many times engaged in war with this king, but this king always vanquished and got the better of him.” Although such information is often refered to in articles, I am suspicious whether the author got them by actually stepping his feet on Java or by hearsay from others, because the descriptions of Java and other parts of the East Indies are quite short and abstract, whereas those on the region to the west of India and the places in China are much more detailed and facts that he must have seen and heard are contained. In fact, in the chapter on Java, which is comprised of only some 250 words, nothing was written about towns and people, while the appearance of the palace described was unrealistically gorgeous.

Desawarnana (alias Nagarakertagama) [66] written in the form of kakawin in 1365 by Mpu Prapanca who accompanied the inspection tour of Hayam Wuruk is one of the two important history books ranked with the Pararaton. The places of visit, including Kagenengan, the mausoleum of Jayasa (Ken Arok), as mentioned above, and the royal line of Singawari, which started from Ken Arok, were given in detail. With regard to the birth of Ken Arok, it was simply written as, “[The king was] visibly a divine incarnation, known as a son not born from the womb to the illustrious Lord of the Mountain [Siva]”, unlike the Pararaton, which described his complex early life. The book also neglected the Bubat War (1357), an incident that must have been most tragic in Hayam Wuruk’s life, in which his marriage to his fiancée Princess Dyah Pitaloka of Sunda was unrealised, due to the plot of Gajah Mada, who had intended to subject the Sunda Kingdom, and all party members of Sunda, including the king, the queen and the princess, perished in the field of Bubat [67]. Such omissions could be taken for granted as the book itself was a song to praise the illustrious royal line. Several years after the tragic incident, Hayam Wuruk married Paduka Sori, his cousin.

After the death of Hayam Wuruk in 1389, the kingdom gradually declined due to troubles with the succession of the throne and, due more to the propagation of Islam. Although when Islam was first introduced in Java is not exactly known, it had spread before the beginning of the 15th century at the latest, as it was written in the Ma Huan’s The Overall Survey of the Ocean Shores (Ying ya sheng lan ) in 1416 that “There are three kinds of people in this country, Moslems who came from western countries for trade, Chinese who exiled from Canton, Zhangzhou, Quanzhou, etc., and natives who worship the heresy [Hinduism].” [68]

In fact, in the middle of the 15th century, the lords of such port towns as Demak, Jepara, Gresik and Tuban on the north coast of Java began to convert themselves to Islam and control the trade independently from Majapahit, and one of them, Raden Patah, founded the Demak Kingdom, the first Islamic kingdom in Java ca. 1475. Although Demak prospered by the trade with Malacca, they lost their power, after the latter fell to the Portuguese in 1511, attacked by Alfonso de Albuquerque, the Governor of India, as written in the book of Tome Pires [69].

The Majapahit Kingdom is generally regarded to have perished after the reign of Brawijaya VI (alias Girindrawardhana, 1478–98) and, around that time, the nobles took refuge with a number of books and cultural heritages of Java to Bali where the Islamic power did not reach. In fact, all copies of literature and history books written before the Majapahit period and remaining to date have been found in Bali and Lombok (an island located east of Bali), thanks to their efforts.

As literary works in the Majapahit period, two kakawins, Arjunawijaya and Sutasoma, composed by Mpu Tantular during the reign of Hayam Wuruk, are known. Whilst the former told a rather simple story taken from an episode of the Ramayana[70], the latter was based on a Buddhist tale, “Maha-Sutasoma”, in the Jataka Sutra, consisting of 562 cantos, and was unique in the Hindu-predominant East Java [71]. Let us follow the story, although it will be a little lengthy.

“King Mahaketu of Hastina was disturbed by the ransacking demons, when he was told by the chief brahmin that only a son of the king would be able to destroy them. As the king practised yoga in front of a Jina (Buddha) statue, a Bodhisattwa entered the womb of his queen to be born as a son. When he grew up, the prince, named Sutasoma, thought the enhancement of his own mental culture should be the matter of priority and stole away from the palace for ascetic practices, to the disappointment of the family. In a village, Goddess Bhairawi appeared to teach him a mantra by which every kind of evil and all hostile powers could be destroyed and mankind would obtain freedom from illness and misfortune. The goddess also directed him to a hermitage on Mt. Semeru and vanished. Sutasoma met a reverend Kesewa, whom he asked to accompany him to the top of the mountain. On their way, they found a hermitage and met a hermit, Sumitra by name, who was a maternal uncle of Sutasoma. The uncle told of the past of the evil king Suciloma. According to him, although his homicide had once been stopped by Jina who came to earth, he was given an unbeatable power by Siva and got the name Jayantaka. One day, he was served a piece of flesh from a human corpse, instead of the dish which had been eaten by dogs. After that, he was fond of human flesh and was called Porusada (man-eater).

“On his way to the mountain, Sutasoma was attacked by Gajamukha (an ogre with an elephant head), a monster serpent, and a hungry tigress who was about to devour her cubs, but with the help of gods, he could dissuade them and made them his disciples. When he went on alone towards the summit of Mt. Semeru, the gods tried to pull him down and let him confront the evil conduct of Jayanta. Sutasoma was not tempted by nymphs despatched by Indra, and his faith was not wavered either, even when Indra himself transformed himself into a dazzling goddess and approached.

“Having completed his practice, Sutasoma was then conscious of being a Jina and saw the task before him. He descended from the mountain and met Kesewa again. He came across Dasabahu, the king of Kasi, who was his cousin, and married the latter’s sister, Candrawati. Sutasoma and Candrawati perceived that they were the incarnations of Wairocana and his spouse, Locana. Sutasoma returned to Hastina Kingdom with his wife, and Dasabahu joined them.

The evil King Porusada was healed from the wound of his leg, which he had suffered earlier in a battle with Dasabahu, by vowing to Kala (God of Death) that he would capture one hundred kings and submit them as victims. When he accomplished his pledge, however, Kala demanded Sutasoma as a sole victim. He headed for Hastina. In Hastina, despite that Sutasoma was willing to sacrifice himself to relieve the captured kings, the ministers prepared for war. In the war, Porusada lost his two allied kings, killed by Dasabahu, in the initial stage but turned the table to chase the Hastina, destroying villages and sanctuaries. At last, Sutasoma went to the battlefield and confronted the enemy.

“Siwa (who entered Porusada) emitted flame, but it turned into amrta (water of life) and revived the fallen kings of the Hastina camp. He shot his arrows, but they changed into flowers. Sutasoma was not harmed, because he was an incarnation of Buddha and ‘Buddha and Siwa are one in their deepest essence’. When he concentrated his mind in the bodhyagri position, a diamond weapon was produced to instantly change Siwa’s anger into complete serenity. Having realised Sutasoma was a Buddha, Siva left the body of Porusada. Porusada was awed by Sutasoma’s willingness to offer himself to spare the lives of other kings, and he was filled with compassion and love.

“Kala was delighted with the appearance of Sutasoma and released the captive kings. He tried to stab Sutasoma, but his sword failed to penetrate his body. Kala then changed himself into a naga (dragon) and started to devour him, when he was suddenly overcome with feelings of benevolence and compassion. He desisted and begged Sutasoma to admit him as his disciple. In Hastina, the dead were revived by Indra and festivities were held. The world enjoyed a time of peace and prosperity. After some time Sutasoma and his consort left the earth and returned to the Jina’s heaven, where Porusada was received as a Jina devotee. Kala attained the status of Pasupati (the lord of the animals). Sutasoma’s son Ardhana succeeded his father as king of Hastina.” [72]

|

A scene of Kala biting into Sutasoma in the form of a dragon. A part of the ceiling paintings in Kerta Gosa Palace, Klungkung, Bali. Reproduced from: http://balitourismculture.blogspot.jp/2009/08/kerta-gosa.html. |