Mataram where Gods and Buddha Reside

Even those who are usually indifferent to Java may remember Borobudur, and the Java Man, if asked what they have learnt in school about Java. The ancient monument, which is rated as one of the finest cultural heritages of the world, had been hidden for more than one thousand years in the depths of the jungle until it was rediscovered in the beginning of the 19th century. It was during the time of the Napoleonic war when Java was occupied by the British that Thomas Stamford Raffles, who was then the Lieutenant Governor of Java and its Dependencies, heard rumours of the “mountain of statues” called Boro-bodo from local inhabitants and he gave an order to conduct surveys to Lieutenant Colonel Ir. H. C. Cornelis who had formerly engaged in the excavation of the Prambanan ruin that had been known about since eighty years earlier. In his great book,The History of Java [1], published in 1817, Raffles wrote about the whole particulars that appeared after the felling of rank tropical trees and the removal of thick soil, as follows:

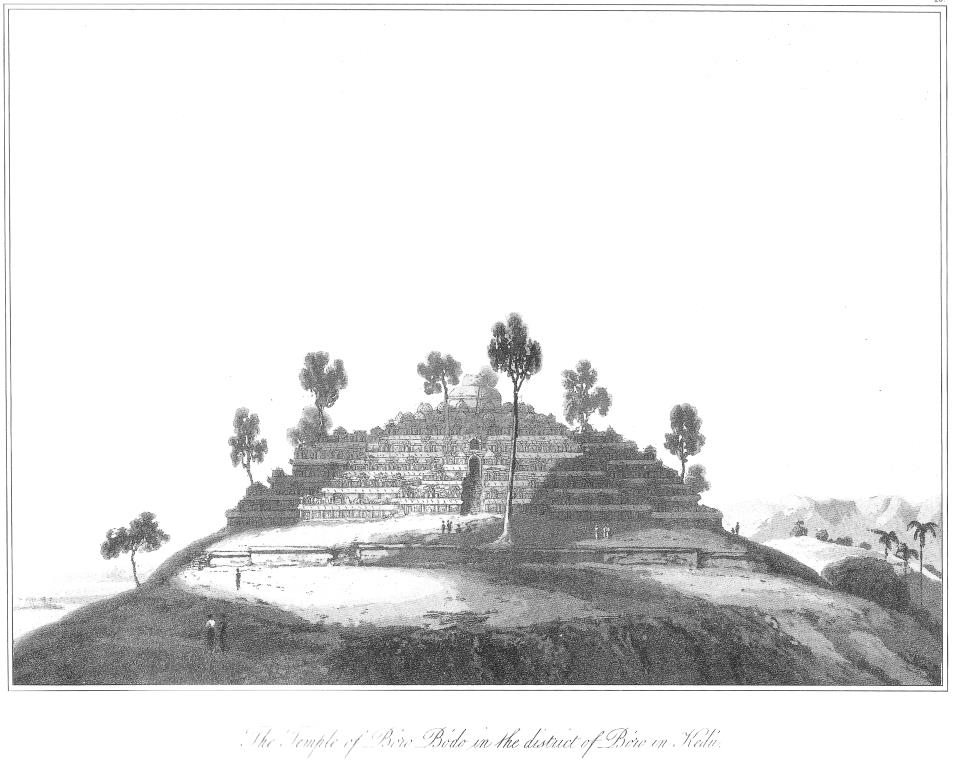

“In the district of Boro in the province of Kedu, and near to the confluence of the rivers Elo and Praga, crowning a small hill, stands the temple of Boro Bodo, supposed by some to have been built in the sixth, and by others in the tenth, century of the Javan era. It is a square stone building consisting of seven ranges of walls, each range decreasing as you ascend, till the building terminates in a kind of dome. It occupies the whole of the upper part of a conical hill, which appears to have been cut away so as to receive the walls, and to accommodate itself to the figure of the whole structure. At the centre, resting on the very apex of the hill, is the dome, of about fifty feet diameter; and in its present ruinous state, the upper part having fallen in, only about twenty feet high. This is surrounded by a triple circle of towers, in number seventy-two, each occupied by an image looking outwards, and all connected by a stone casing of the hill, which externally has the appearance of a roof.

“Descending from thence, you pass on each side of the building by steps through five handsome gateways, conducting to five successive terraces, which surround the hill on every side. The walls which support these terraces are covered with the richest sculpture on both sides, but more particularly on the side which forms an interior wall to the terrace below, and are raised so as to form a parapet on the other side. In the exterior of these parapets, at equal distances, are niches, each containing a naked figure sitting cross-legged, and considerably larger than life; the total number of which is not far short of four hundred. Above each niche is a little spire, another above each of the sides of the niche, and another upon the parapet between the sides of the neighbouring niches. The design is regular; the architectural and sculptural ornaments are profuse. The bas-reliefs represent a variety of scenes, apparently mythological, and executed with considerable taste and skill. The whole area occupied by this noble building is about six hundred and twenty feet either way.

“The exterior line of the ground-plan, though apparently a perfect square when viewed at a distance, is not exactly of that form, as the centre of each face, to a considerable extent, projects many feet, and so as to cover as much ground as the conical shape of the hill will admit: the same form is observed in each of the terraces.

“The whole has the appearance of one solid building, and is about a hundred feet high, independently of the central spire of about twenty feet, which has fallen in. The interior consists almost entirely of the hill itself.”

|

Borobudur Temple in Boro District Kedu Reproduced from: Antiquarian, Architectural, and Landscape Illustrations of the History of Java 1844/John Bastin (preface), Plates to Raffles's History of Java, Oxford University Press, 1989 (Vol. II). This sketch was made by Ir. H. C. Cornelis who conducted the first excavation in 1815. |

This news startled the world. It was thirty years earlier than the discovery of Troy ruins by Heinrich Schliemann that was said to be the monumental epoch in the history of archaeology. Who had built such a magnificent structure and when? I read somewhere that among Europeans was someone who believed their superiority to other races raised such a nonsensical speculation that it must have been constructed by Alexander the Great when he reached there during his eastern expedition [2], because it was hardly possible by Asians.

Nevertheless the wider view was such that the temple had been built by the natives in the 8th–9th centuries when Hindu-Buddhist culture prospered there, long before Islam propagated around the island of Java. Presently, it is commonly understood that the founder was King Samaratungga of the Sailendra and that the year of its completion was 824 AD, as described below.

Although Raffles’s rule was not necessarily successful and left various problems, the Dutch appreciated his efforts for promoting the study of ancient culture of Java and followed the survey of this and other remains, after the restoration of the East Indies to the Netherlands in 1816. The second survey was conducted by the middle of the 19th century and, after the emergence of photography, Borobudur became widely known in the world. A famous naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace, who visited the East Indies in the 1860s concluded his paragraph on Borobudur as, “The amount of human labour and skill expended on the Great Pyramid of Egypt sinks into insignificance when compared with that required to complete this sculptured hill-temple in the interior of Java.” [3] Indeed, it would not be only myself who had the same thoughts as Wallace, after visiting the two sites. While the Egyptian pyramids were a mere stone masonry, the scenes on the bas-reliefs, which Raffles described as “mythological”, had turned out to be not just ornaments but the pictorial explanations of the biography of Gautama and various other sutras. This tradition of “narrative sculptures” was inherited in the temples built shortly after then in Prambanan Plain as well as those constructed in the 12th to 15th centuries in East Java.

Since the concept to preserve such ancient ruins as of Borobudur as cultural heritage was yet to be common in the later 19th century, several pieces of Buddha’s statue were presented to King Chulalongkorn of Siam (the present-day Thailand) when he visited Java, and a tea hut was put on the tower (“central spire”, in Raffles’s term) for sightseers, as taken in a photograph which remains to date. The array of stone pieces in Borobudur was still significantly disordered and irregular at that time. It was after the turn of the 20th century that proper archaeological research commenced and the necessity of preservation was voiced.

The first large-scale restoration was conducted in 1907–11 under the direction of Ir. van Erp, in which as many as one million stone pieces of one hundred thousand tons were registered and rearranged. Marquis Tokugawa who visited there ten years later wrote in his famous essay that, “The Buddhist monument even looked more precious, when I thought over the time and effort that had been spent for the restoration.” [4] I recall this meaningful comment by a scientist and historian whenever I visit this and other ancient remains.

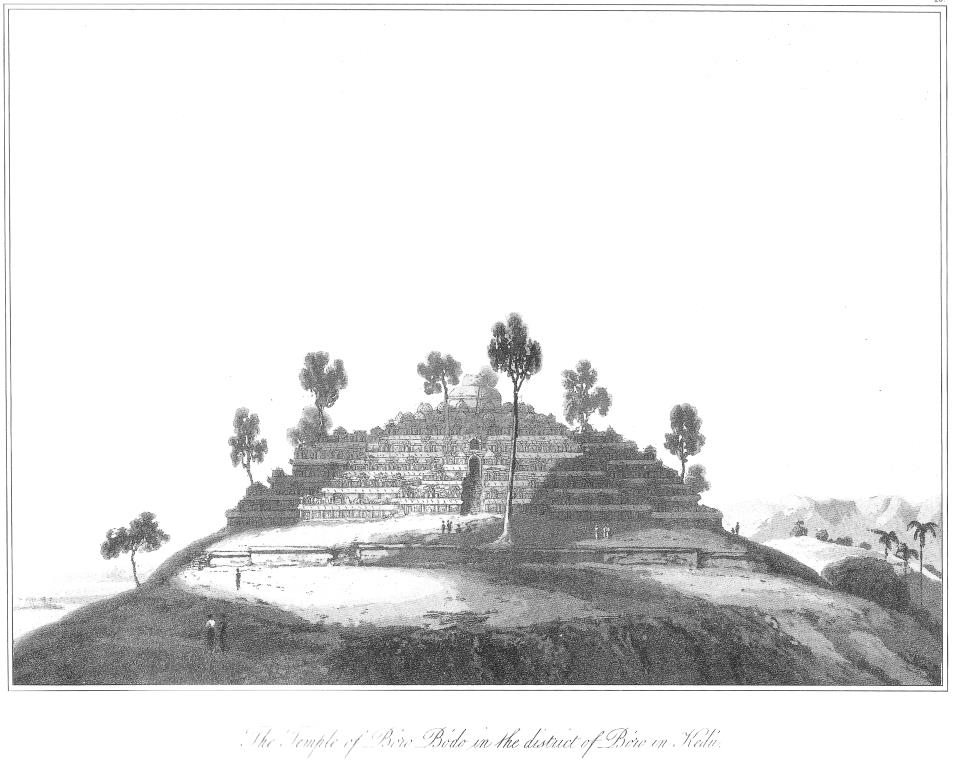

The structure of the temple was not a normal building but, as described by Raffles, an object that stone pieces were layed on the surface of a rhyolitic hill covered by clay. The centre of the dome, which was not clear in Raffles’s description, consisted of three layers of circular terraces, the number of stupas (Raffles’s “tower”) on them being 16, 24, and 32, from the top to the bottom, respectively (i.e. 72 in total). Regarding the dome itself as a gigantic stupa, a pole threaded with finial rings was once added on top of the tower, but it was removed later for the lack of historical evidence[5].

|

Cross-section of Borobudur. Redrawn on: Karl With, Java – Brahmanische, Buddhistische und Eigenleige Architektur und Plastik auf Java , Filkwang Verlag. M. B. H. Haben 1. W. 1920. Red lines to indicate the locations of reliefs have been added by the present writer. |

Such a ringed pole, which can be seen in an old picture of Borobudur, can also be seen today on the office building of West Java Government in Bandung, nicknamed “Gedung Sate”, which is a famous building of Dutch–Javan eclectic style, built in 1924, designed by Ir. J. Gerber, a young architect from Delft Technical Highschool. It was when I guided someone from countryside Java during my stay in Bandung that the hungry guest fell into disappointment, having misunderstood that Gedung Sate was not a sate-house that served “sate”, a skewered meat that was a popular cuisine in Sunda (“gedung” means a “building”). In reality the nickname has its origin on the side view of the ringed pole, which looks like “sate” from the distance, while the architect must have faithfully imaged the ringed pole of a Buddhist temple.

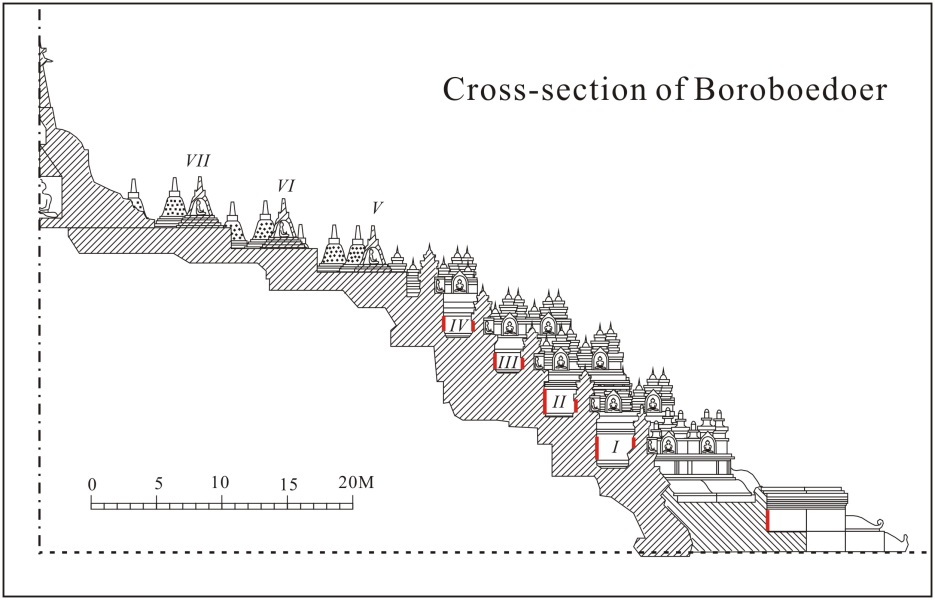

In the Borobudur temple, the numbers of niches on the five terraces were 104, 104, 88, 72 and 64, from the bottom to the top, respectively, and 432 in total, the sum of Buddha statues was 504, by adding those in the 72 stupas on the upper circular terraces. Although those sculptures are similar in both size and shape so that their difference is not easily noticeable for amateurs, their names and the mudra have been identified in detail[6].

|

The ground plan of Borobudur Temple Redrawn on: Stutterheim, W. F., Pictorial history of civilization in Java. Translated by Mrs. A. C. de Winter‑Keen, The Java Institute and G. Kolff & Co., Weltevreden, 1926. |

It is said that one more uncompleted sculpture of Buddha was discovered during the survey by Hartmann in 1842 in a small cell that existed in the interior of the central tower, and aroused interest at that time, but it could have been a trick by someone to plot a big discovery, as conjectured by Dr. N. J. Krom5.

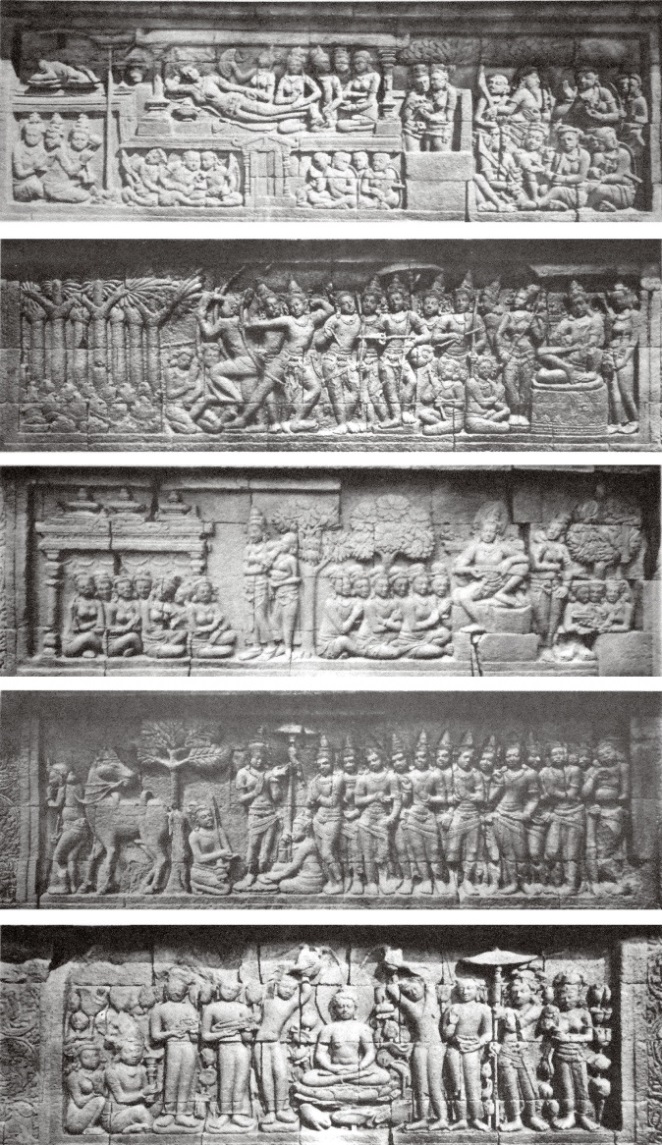

Bas-reliefs on the outer wall of the basement and both side walls of the four corridors were as many as 1,300 in number, and they have been interpreted to represent such sutras as Lalitavistara, Jataka, Avadana, etc.[7] Although these sutras are certainly not at all easy to read, at least for myself, the reliefs depicting the life of Gautama (Lalitavistara) on the panels on the main wall of the first corridor can be followed by ordinary visitors. They begin with a scene of Bodhisattva in the heaven and through the scenes of Maya’s conception by seeing a white elephant in her dream, Gautama’s birth and growth, his renouncement from the world and so on, and end with his first lecture.

|

Five scenes from 120 reliefs on the first corridor-parapet (upper row) of Borobudur, showing the Gautama’s life. From the top, [No. 13] Maya dreams a sacred dream, [No. 49] Gautama shows talent of archery, [No. 51] Gautama marries Gopa, [No. 66] Gautama parts from his horse and attendants to go into religion, [No. 120] Gautama gives his first lecture after ascetic practices. From: Hidenosuke Miura (Ed.), Buddhist monument Borobudur in Java: Folder 1–3, Borobudur Publishing Society 1924 (三浦秀之助撰,「闍婆仏蹟ボロブヅウル第1-3帙」,ボロブヅゥル刊行会 1924). By courtesy of The Tokugawa Art Museum Library. |

Besides those exposed reliefs, 120 panels with carvings of some scenes of karma (Mahakarmavihanga) hidden under the ground on the wall of the basement were unearthed and photographed by Dr. J. W. Ijzerman in 1885, before the first restoration, but were buried again, having been judged that the basement had been covered with soil, in the course of the construction of the temple, by changing the original design, in order to reinforce the upper structure. In fact, some of the reliefs were unfinished according to photographs taken at that time.

In addition to those Buddha statues and the reliefs, the building of Borobudur is also ornamented with sculptures, such as Makara, a sea-creature in Hindu mythology, being placed at the foot of each staircase, and of the head of Kala (Kirtimukha in Sanskrit means "Glorious face"), the god of death, which originated from Hinduism, being put upon each gate, as well as carvings of various animals, birds and flowers on the frames on the wall and everywhere. One cannot but admire the elaborate and sophisticated idea of the designer.

As to the attributes of the temple, there is one common view that Borobudur was not a stupa but a representation of the tridhatu, the basement with the hidden relief being the Kamadhatu (desire-realm), the square terraces with those of sutras being the Rupadhatu (fine-material-realm) and the upper circular terraces being the Arupyadhatu (non-material-realm). W. O. J. Nieuwenkamp (1874–1950), a Dutch scholar and painter, well known for his fine sketches and woodcuts of Java and Bali, had assumed that Borobudur had represented a huge lotus flower floating on water and drawn such a picture in 1931, judging from the ground-plan of the temple on some unearthed artefacts depicting a lotus rosette and petals around a circular flower-bed, and the results of water-level surveys, which showed that the Kedu Basin beneath the 235-metre elevation line was once a lake [8]. Although his theory was fiercely criticised by Ir. van Erp[9], Dr. Soekmono [10], a current authority of Borobudur wrote that Nieuwenkamp’s hypothesis should not necessarily be rejected as further geological investigation produced evidence in favour of his idea.

The theory to consider Borobudur as a representation of mandala was raised earlier in 1925 by Prof. Seigai Ōmura, an eminent art critic and professor of Tokyo Fine Art School. With reference to his deep knowledge on Buddhist art, he wrote in an article contributed to Prof. Miura’s book [11] that “Borobudur is neither a vihara (temple), a caitya (tower) nor a stupa, but a great stone construction of karma mandala, one of the four types of mandalas” and that “this had not been perceived by scholars in the world due to their deficient understanding of Esoteric Buddhism.” Unfortunately, his paper does not seem to have caught wide attention, until today, because it was written in Japanese in the not for sale, limited edition book of only 200 copies printed.

Dr. Krom who engaged in the restoration in the early 1900s began the first chapter of his great book [12] as follows:

“Namo Buddhaya! Hail Buddha! No words more suitable than these could be found with which to begin our description of this mighty monument. How often they must have echoed through the galleries and over the terraces of the Barabudur! To comprehend fully the meaning of this most splendid creation of Hindu-Javan culture, we must transport ourselves, as far as possible, into the mind and spirit of those who, 1,100 years ago, worshipped reverently at the feet of the Lion of the Sakya-race, the Omniscient, the Protector of the Earth in divine majesty.”

Whilst the pilgrims in those days are supposed to have climbed the staircases, led by monks in robes, and received lectures of sutras in front of the reliefs on each terrace, until finally feeling refreshed when they stood on the top terrace, we have to hire a guide in a casual shirt today, as no monks are available in this religiously abandoned temple. Once I met a guide who had profound knowledge on Buddhism, despite the fact that he was a Moslem, and spoke English, Dutch and Japanese. I visited Borobudur for the first time in the mid-1980s and many more times after that during my stay in Bandung and Bogor, to accompany my guests, and experienced every time that I was unconsciously saying, “Namo Amitabha!”, filled with some deep emotion, even though I was not pious in my daily life.

An eminent scholar of English literature and novelist, Tomoji Abe, wrote in his book[13], “It is said that those who wish to visit the Buddhist remains of Borobudur ought to arrive there before the daybreak and see the sun rising above the peak of Mt. Merapi[14] from the top of the temple.” I do try and arrange myself to do so whenever my schedules permit. Borobudur is located 40 km north by northwest of Yogyakarta, the principal city of Central Java. If you stay there the previous night, you should get up at 4 o’clock in the morning with the voice of azan (adhan) from a near-by mosque to urge the praying for Allah as the alarm to go to the Buddhist temple. If scheduled to go straight by night train, which arrives from Jakarta or Bandung to Yogyakarta around 3 o’clock in the morning, you must start soon after depositing luggage and sipping a cup of coffee in the station or a near-by hotel. Driving in the dim light for one hour, one arrives at Hotel Manohara near the precinct of the temple, and pays the admittance there. It is still pitch-dark at 5 o’clock. With the aid of a torch given from the hotel, you can sense the stone construction and find one of the four staircases that lead to the upper terraces. On the top of the temple, if Mt. Merapi is not active and no glow is seen on its summit, check the east direction by means of a compass and sit for a while.

|

The sunrise seen from the top terrace of Borobudur. Top: 19 June 2004, 5:34’32” Bottom: ditto, 6:05’22” (West Indonesia Time). Photographed by M. Iguchi. Peaks on the left (north) and right (south) are Mt. Merbabu and Mt. Merapi, respectively. Ash is seen trailing on the right-hand side of Merapi’s peak. |

After half past five, a scene appears that reminds one of the first paragraph of Sei Shonagon’s Makura-no-Sousi ( The Pillow Book):

In spring, the dawn – when the slowly paling mountain rim is tinged with red,

and wisps of faintly crimson-purple cloud float in the sky.[15]

Then, one can extend the depiction with respect to the mountain by recalling a tanka (short poem) by Rev. Ji-en, compiled in Shin-kokinshu:

On the plain of heaven,

The smoke from Mount Fuji,

Trails in the sky of dawn of spring colour. [16]

and replacing Fuji with Merapi, the latter being also a beautiful “konide”, or conical strato-volcano. Although the four seasons are not present in Java of the ever-lasting summer, the air in the early morning is very soft to the skin as in the spring of mid-latitude countries like Japan. A big difference from those countries is the fact that there is almost no period of twilight in the morning and evening in this low-altitude country. Within a matter of half an hour before the sunrise, the colour of the sky dramatically changes. Located at 110°2" E and 7°36" S, while the West Indonesia standard time line is set at 105° E, the sunrise at Borobudur is around six o’clock throughout the year, the deviation being only a few minutes, but the angle or the position of sunrise related to the axial tilt of the earth is largely variable. Isaw the sunrise once around the summer solstice between Mt. Merapi (2,930 m) and Mt. Merbabu (3,142 m), the latter being located 10 km to the north, but the sunrise was shifted far to the southern foot of Merapi in February.

When the morning mist at the circumference of the monument below clears, being radiated by a godly sunbeam, a beautiful landscape in which palm woods are scattered in the flat fields appears. In the southern direction is seen the mountain range of Menoreh, the skyline of which is said to resemble the lying posture of Gunadharma, the legendary architect from Ceylon who designed Borobudur [17]. The left-hand or the eastern side of the mountain ridge in particular looks like the profile of a man’s face with a low nose and a small chin. To the northwest one can view Mt. Sumbing (3,371 m), which also resembles Mt. Fuji in the distance with Dieng Plateau in the background.

|

A view of Mount Menoreh from the top terrace of Borobudur Temple. Photographed by M. Iguchi, May 2009. |

|

The first corridor of Borobudur Temple (The late Mr. Yoshinobu Tokugawa and a guide). Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2001. |

If visiting Borobudur in the daytime, one must walk from the car park through the row of souvenir shops to the main gate and buy a ticket. On entering the approach through the grass field decorated with tropical flowers of vivid colours, the whole view of the temple appears. The temple looks like a crown and one can feel comfortable only up to there. On arriving at the staircase of the building, the visitor becomes drenched in sweat all over the body by the radiant heat from the stones scorched by the sunbeam from right overhead to such an extent that a fried egg may be cooked on the surface.

The sunset at Borobudur is said to present a different grace, although I have not seen it. Marquis Tokugawa wrote as follows [18]:

“When I had a look from the side of the tower, the red sun was about to set behind the mountains that stood in the distance beyond palm fields. It was a gorgeous sunset at an ancient Buddhist monument. What a quiet and tranquil scene it was! The glory of the sunset made the lonely traveller’s loneliness even deeper.”

Another traveller, Frank Carpenter, wrote about the Buddha statues fantastically lit up at midnight by the ray of a full moon, surrounded by dark mountains that must have been more fantastic than his description in words[19].

The area in the periphery of Mt. Merapi extending from the Kedu Basin to the west, to the Prambanan Plain to the south and to the Solo Plain to the east is the most fertile land in fertile Java, thanks to the volcanic ash incessantly scattered from the volcano, and was called Bhumi Mataram [20], or the Soil of Mother, where indigenous people inhabited ever since ancient time. In the vicinity of Magelang, ten kilometres north of Borobudur, lies the hill of Tidar, known as the “Nail of Java”, which according to a tradition had fixed the island of Java when it was floating in the sea. Thus, it was reasonable that this location had been chosen as the site to construct this holy temple.

The Borobudur temple is locally called Candi Borobudur. Although the word, candi, derived from Candika, an alternative name of the Hindu Goddess Durga, formerly denoted the mausoleums of kings and nobles or the temples for Hindu-Buddhism statues [21], it became generally applied in later centuries to old religious structures built prior to the Islamisation of Java. Let us adopt this word, candis for its plural form, in the text below.

Accounts of Borobudur in old documents

Although it was The History of Java of Stamford Raffles that aroused interest in Candi Borobudur in the world, some descriptions on the same candi did exist in Java. In a book published for commemorating the restoration in the late 20th century [22], two examples were cited. One was Babad Tanah Jawi (Chronicle of the Land of Java), which recorded that a certain Ki Mas Dana who had rebelled against King Amangkurat in vain was killed in 1709 at the Hill of Borobudur. The other was in Babad Mataram (Chronicle of Mataram) in which it was written that Crown Prince Mancanagara of Yogyakarta who went to the forbidden “Mountain of one thousand statues” to meet a miserable satria (warrior) who was enclosed in a cage, died of a disease on the next day of his return. The satria was no doubt one of the Buddha statues in the stone-basket stupa on the upper terrace of Borobudur.

Borobudur visited by a scholar in The Centhini Story

I had also learnt from the brief view on Google Books on the internet that some descriptions on Borobudur had existed in the Serat Centhini (The Centhini Story), a book that included a variety of knowledge on early 17th-century Java. In the copy I had recently obtained[23] in the Taman Pintar book market in Yogyakarta was a detailed story, the abstract of which is as follows:

“Along the way, Mas Cebolang recalled the happy times with his wives, who were like the angels in the abode of Indra. The difficulties and loneliness he encountered on his journeys had sharpened his desire to return to the conveniences of life with them. It was only when he came to a forest that his heart could beat in rhythm with the warble of birds and the sound of nature. By virtue of his upbringing as the son of a great ascetic, his lips mumbled formulas of praise and gratitude towards The Almighty. Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar! (The God is great!).

“His steps were guided by faith and stopped only by a stupendous sight, for in front of him loomed an impressive stupa. Although there were already signs of decay due to the ravages of time, the stupa of Borobudur, since its foundation ten centuries ago had always been able to instil feelings of adoration, peace and security among Buddhists and non-Buddhists, with the exception of people without faith.

“Mas Cebolang walked up the temple steps and inspected the reliefs on the walls, which recounted tales from the Jataka stories [stories of living beings who later became the Buddha after living according to religious guidance] and those of noble people who traveled around looking for knowledge and life experiences. He felt inspired when he stopped in front of a Buddha statue with its hands in the dharmmacakra position, which denotes the Buddha instructing the people to live according to the teachings and guidance of the Creator. The Buddha appealed to humanity to follow his path towards nirvana [heaven].

“Likewise, Rasulullah [the Messenger of God] Muhammad ordered his followers to follow his way of life as an example, which was none other than the implementation of the teachings of the holy Qur’an. Tears welled up in his eyes and rolled down his cheeks. As the sun was setting, Mas Cebolang decided to pass the night in the temple. Later, a full moon shone brightly against a blue cloudless sky, its beauty almost perfect. And on Earth, amongst the Buddha statues and, whilst his attendants were snoring, Mas Cebolang was deep in contemplation.” [24]

As might be expected of a scholar who later married a daughter of the Sunan Giri, a famous family of their cultural tradition, Mas Cebolang’s understanding of the Borobudur reliefs was just right, despite the fact that his religious background was Islam. The fact that he showed profound reverence to Buddha without prejudice to the divinity of a different religion would be attributed to the characteristic of the Javanese who had respect for their ancestors’ faith. The condition of Borobudur at that time is supposed to have been much better than that observed two hundred years later by Stamford Raffles and other visitors.

The origin of the name Borobudur

What was the origin of the name Borobudur? Unfortunately, no hint for answering this question was available in those documents in Java. Apart from a speculation by Stamford Raffles as “Great Buddha”, an authority of Javanese palaeography, Dr. Poerbatjaraka had once proposed that “boro” would mean the Sanskrit “biara” for monastery, and “budur”, the name of a sanctuary of the Vajradhara sect of Mahayana Buddhism, which appeared in Nagarakertagama (or Desawarnana), a chronicle composed by Mpu Prapanca in 1365 AD. Later, Prof. de Casparis interpreted that a word, “Bhumisambhara-bhudhara” appeared in Prasasti Karang Tengah [25], dated 842 AD, meant “The mountain of the accumulation of virtue on the ten stages of the Bodhisattva” and that it was the original name of Candi Borobudur [26].

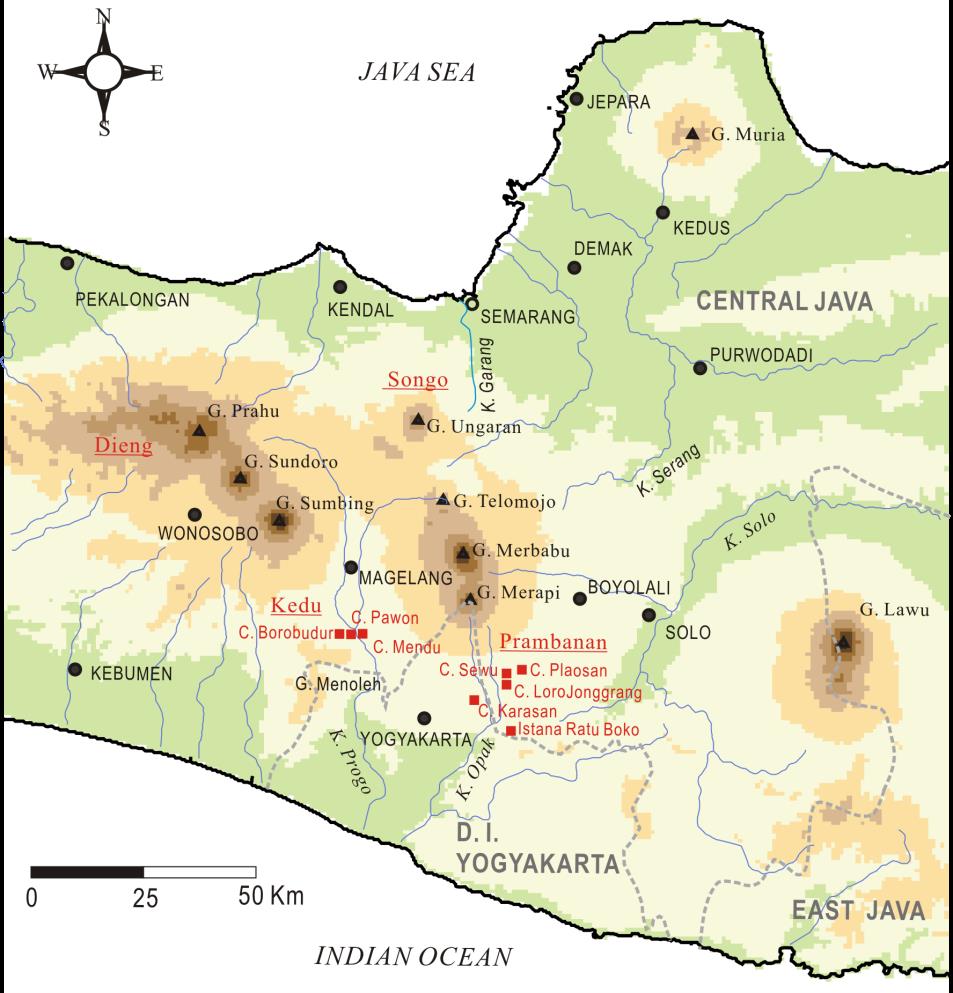

Candis that remain in Central Java

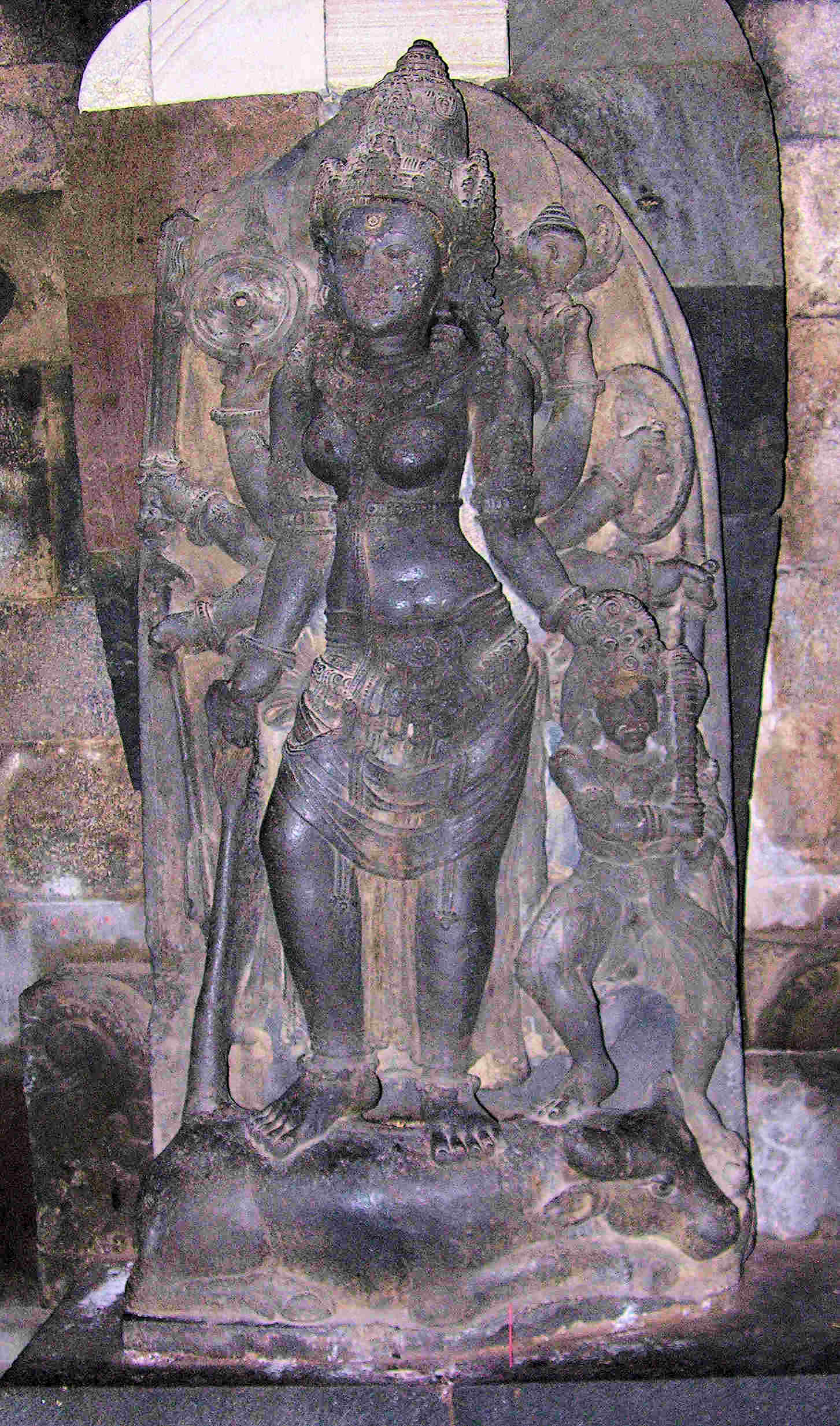

In central Java, there remains a number of candis, retaining their original superstructure, although the majority of those built in the past, which is estimated at as many as more than 280 in number, have either completely disappeared or retained only some stone pieces [27]. In the vicinity of Borobudur, one can find two more nice candis: Candi Mendut, which houses a large Shakyamuni Buddha Triad (or Shakyamuni Triad, i.e., Shakyamuni flanked by two attendants) in its niche, and Candi Pawon, which is small but elegant and lovely. In the Prambanan Plain, a group of Hindu candis, called Candi Loro Jongglang (commonly known as Candi Prambanan), which rank with Borobudur in their scale and magnificence stand, along with Buddhist Candi Kalasan, Candi Sewu and others. There are eight old Hindu candis in Dieng Plateau, and some more in Gedung Songo on the slope of Mt. Ungara, although I have not been to the latter place [28].

|

Historical sites in Central Java G (Gunung)=Mountain, K (Kali)=River, C (Candi)=Temple. The topographical map was prepared with DIVA-GIS Country Level Data. |

A beautiful statue of Shakyamuni in Candi Mendut

Candi Mendut can be easily accessed as it is located 2.9 kilometres to the east of Borobudur on the highway from Yogyakarta. When discovered in 1834, this candi was buried in a jungle in such a condition that only its top part was exposed on the ground, and many stone blocks had been taken away by near-by inhabitants for their housing. Having been restored in 1908 by Ir. van Erp, the candi stands with a dignified appearance in a precinct, as wide as a soccer field, surrounded by banyan and other tropical trees. On the basement with a staircase in its front side, which measures 24 metres wide, 28 metres deep and 3.5 metres high, a massive temple with a floor size of 13.7 metres square towers. The pyramid-shaped roof ornamented with small stupas has now been restored over the last few years, and the total height is 26.4 metres, whereas the top part of the temple was still flat when I visited there in 2003. The whole surface of this candi is decorated with elaborate carvings. On the three outer walls, on the left, the back and the right sides of the building, are huge bas-reliefs of 3.5 metres wide and 2.5 metres high, which depict eight-armed Tara, four-armed Kwannon and four-armed Tara, respectively. On the wall of the entrance to the niche, there are beautiful reliefs of Hariti (goddess of childbirth and children), Yaksha (demon warrior) and others, in which the elegant “flying celestial being” appeared most attractive to me. Probably a whole day will be necessary if you wish to see all of the building’s detail.

In the niche, one finds a big statue of Shakyamuni Buddha, which is about 3 metres tall, flanked by statues of Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara and Bodhisattva Vajrapani, both of 2.5-metre height, on the left- and right-hand sides, respectively. The nimbus for them looked rather small for the size of the statues. One feature that looked interesting to me was that each of them was sitting on a chair, the Shakyamuni hanging both legs down, the Avalokitesvara and the Vajrapani horizontally folding their left and right legs, respectively, because most Buddha statues, including all of those that I saw in Borobudur and elsewhere, sat cross-legged or stood upright. I speculate that the monk who ordered these statues might have been influenced by Hellenism in India or somewhere else. The mudra of Shakyamuni was apparently the wheel-of-law turning mudra, whereas those of the Avalokitesvara and the Vajrapani looked to be the blessing mudra and the earth-touching mudra, respectively. Besides the fact that the surfaces of these sculptures were well finished and smooth as if they were not made of a stone but a metal, I was impressed by the beautiful face of Shakyamuni, which was rather long-shaped with a shapely nose, not round like those in Borobudur or the giant statues of Buddha in Nara and Kamakura, Japan.

|

The Shakyamuni Triad in Candi Mendut. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012. |

|

Upper part of Candi Mendut (viewed from the southeast) Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2007. (The top of the upper part was unreconstructed and flat in pictures taken in June 2004.) |

In the outside of the dark niche, the green leaves, the yellow aerial roots and the dark-brown trunks of banyan trees showed a vivid contrast under the bright sunlight. It was when I visited there for the first time that a famous tanka (short poem) by Akiko Yosano [29] came up in my mind. She sang:

|

Here in Kamakura the sublime Buddha is of another world, but how like a handsome man he seems, adorned with the green of summer. |

Later, I found the same impression given by Yusuke Tsurumi [30] in his old travelogue, i.e. “If this were shown to the genius Akiko, the phrase of ‘how like a handsome man he seems, adorned with the green of summer’ would have been produced in Mendut.”

In the Serat Centhini, there were some descriptions on the visit of Mas Cebolang to Candi Mendut. He was so deeply moved also by this candi that he spent the night in the niche together with the statues of Buddha and Bodhisattvas.

Relatively recently, I saw a signboard of “Mendut Monastery” outside of the precinct of Candi Mendut and visited there with my friends. It was a cosy, modern monastery. An entrance path lined both sides with several stone stupas of about two metres tall stretched straight forward seen from the gate and a small temple and a monk’s quarters, both single-storey, were situated on the left- and right-hand sides. The chief priest came to guide us after receiving a notice from an apprentice who was cleaning the ground. About ten metres ahead by the side of the path was a standing statue of Bodhisattva guarded by a sculpture of raksasa (giant) and at the end of the path was a big stupa of five- to six-metre height. On the left-hand side, there was a small hall of traditional Javanese architectural design, called pendopo, in the middle of a lotus pond, and in the hall was enshrined a statue of cross-legged Shakyamuni, made of white granite, with a golden halo behind, which looked rather new. According to the chief monk, it was presented in 2002 by Rev. Ryogen Furusho of Zenyouji Temple, Kawasaki, Japan, as written on a commemorative tablet. He told us that their denomination was Mahayana Buddhism. He also told us with deep emotion that now the monastery had such beautiful statues, buildings and garden and six members, whereas it had only humble bamboo huts when he opened the monastery twenty years ago with one of his colleagues. To my question, “Are you also taking care of Candi Mendut?”, he replied, “The candi is maintained and cleaned by the government, but we perform rituals several times a year.” I thought that the Shakyamuni Triad who had no pilgrims for ten centuries would be pleased and left the monastery by offering some banknotes for incense.

|

A statue of Shakyamuni in the Mendut Monastery and the chief monk. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2007. |

Both Buddhism and Hinduism were, of course, brought from India. Although the migration of Indians to Java would have commenced ever since prehistoric time, one party who immigrated and built their own kingdom is said to be Aji Saka and his followers who arrived around 78 AD, and the location of their settlement, Medang Kamulan, is supposed to be somewhere around the present-day Semarang. According to tradition, they had to fight against Negroids, whom they called “Rasaka” (wild devils), who had inhabited there, since before the migration of Javanese, and were still in existence at that time[31]. The Indians introduced their culture and social systems and taught letters, i.e. the Sanskrit scripts from which Java Kawi was derived in later centuries, as well as calendar, i.e. called Saka Calendar, in which the year of Aji Saka’s arrival or his death, 78 AD, was defined as the first year. The fate of their kingdom is uncertain at least to me.

Sanjaya Dynasty – Records in Prasasti Canggal

The first dynasty evidently existing in Java was the Sanjaya Dynasty. The name of the first king, Sanjaya, was recorded in a stone inscription, called Prasasti Canggal, written in Pallava script and dated 732 AD (654 Saka), which was discovered early in 1879 at the site of a ruined temple at Canggal in the south Kedu. Although its abstract is repeatedly cited everywhere, let me translate the contents from the Indonesian text [32] in a faithful manner (S = Stanza).

|

S1 |

[This is the monument for] The construction of Linga by King Sanjaya on the mountain. |

|

S2–6 |

Homage to Lord Shiva, Lord Brahma and Lord Vishnu. |

|

S7 |

Java is very prosperous, rich in gold mines and much production of rice. On this island, Shiva Temple was built for the happiness of people with the help of residents of Kunjarakunja Village. |

|

S8-9 |

The island of Java was formerly ruled by Sanna who was very wise, fair in his actions, brave in war and generous to his subjects. On his death, the country mourned, being sad for the loss of the protector. |

|

S10–11 |

The successor of King Sanna is his son named Sanjaya who is likened to the Sun. Power has been handed over to him not directly from King Sanna but through the king’s elder sister, Sannaha. |

|

S12 |

Prosperity, security and tranquillity [is maintained in] the country. People can sleep in the middle of roads, do not need to be afraid of thefts and robberies, or the occurrences of other crimes. People live all happily. |

The Kunjarakunja village in this prasasti is supposed to be in the vicinity of Sleman-Muntilan in the Kedu Basin at the west foot of Mt. Merapi.

According to a copper inscription, called Prasasti Mantyasih, left by King Balitung in 907 AD, the family line of the Sanjaya commenced by Ratu Sanjaya and the name of Balitung himself was found in the last, eighth place[33]. Sanjaya’s name bore a royal title as Rakai Mataram Sang Ratu Sanjaya and, hence, the kingdom was called the kingdom of Mataram [34] in later times.

Sailendra Dynasty – Records in Prasasti Kalasan

With regard to the Sailendra Dynasty, which had presumably existed around the same age, mention was found in a stone inscription, called Prasasti Kalasan, discovered at a Buddhist temple, Candi Kalasan, in the Prambanan Plain, leading to a presumption that the dynasty was prosperous to such an extent to be able to have such a fine temple. The translation of the content of the inscription from the Indonesian text is as follows [35]:

|

S1 |

Prayer and homages to Arya Tara, hopefully the devotees can achieve their goals. |

|

S2–3 |

Teachers of the king of Sailendra asked Maharaja Dyah Pancapana Panangkaran to construct Candi Tara. The petitions of the Teachers are the building of a statue of Dewi Tara, the temple, and several houses for the priests who are versed in the knowledge of Mahayana discipline. |

|

S4-6 |

The three high tax officers [36] received orders to make Candi Tara and houses for priests. Candi Tara was founded in the affluent land of the king, who became “The decoration the Sailendra”, for the benefit of the teachers of the king of Sailendra. In the year Saka 700 [782 AD], Maharaja Panangkaran finished building of Candi Tara, where the Teachers made offerings. |

|

S7-9 |

Kalasan Village was awarded. The three high tax officers, the prosecutor of the village and high officials became the witnesses. The land gifted by the king are well guarded by the king’s successors of the Sailendra Dynasty, by the successors of three high tax officers and officials who are wise. Then, the king repeatedly asked all kings who will rule later that the temple shall be preserved forever for the happiness of all people. |

|

S11–12 |

Thanks to the construction of the monastery, everyone is expected to gain more knowledge about the birth, obtain and follow tibavopapanna [37] and follow the teachings of Jina. The noble Kariyana Panangkaran repeated his request to all kings who will follow to complete the monastery into the perfect state. |

The “Candi Tara” must be no other than Candi Kalasan and the ruling king of the Sailendra is regarded to be King Wisnu (alias Dharmatunga) who was mentioned in a contemporary inscription, left in Ligor [38], Malay Peninsula, as “a brave killer of enemies”.

The name of King Indra, the successor of King Wisnu, appeared in a stone inscription, named Prasasti Kelurak, dated 782 AD, discovered in Kelurak village in the Prambanan Plain, which mentioned that “Sri Sanggrama Dhananjaya [the throne name of Indra] gave an order to construct a sacred Buddhist temple to house the statue of Manjusri who held the wisdom of Buddha, dharma [law] and sangha [priests]” [39]. The temple is regarded as Candi Sewu in the Prambanan Plain.

In this connection, I may add that there is a proverb in Japan, “If three persons gather, they can produce an idea comparable to that of Manjusri.” To my shame, I have never thought about the true meaning, but the proverb may be better corrected as “One must rely upon the three treasures (Buddha, dharma and sangha) to attain the wisdom of Manjusri”, although no mention was found in dictionaries I have ever checked. In fact, the wisdom of Manjusri could not be obtained even if three mediocre persons gathered together.

The construction of Candi Borobudur

With regard to the construction of Candi Borobudur, a hint was available in the aforementioned Prasasti Karang Tengah, dated 824 AD. Although the inscription, which consisted of two parts written in Sanskrit and Old Javanese, was partially damaged, the contents were interpreted by Dr. de Casparis. In the first part, it was written in Sanskrit, that (1) Pramodawardhani, daughter of Samaratungga (reigned 812–33 AD), built a Jinalaya (Buddhist temple) and placed a beautiful statue in Saka 746 (824 AD), which shines as if the moon descended on the earth, and that (2) the establishment of a Jinamandira (Buddhist temple) called Srimad Venuvana (Sublime Bamboo-Grove) is expected to earn the reward of accomplishing the tenth stage of Bodhisattva’s career to become a Budda and, as long as gods reside on Mount Meru and the sun shines in the sky for the life of thousands of inhabitants, the temple is hopefully full of the virtue of Buddha; while in the second part of Old Javanese language was read that (3) Rakai Patapan and his wife had donated rice fields (for a temple) and villagers were invited as witnesses [40].

Although the names of the three temples were implicit in this inscription, Dr. de Casparis concluded with reference to the records in other inscriptions that (1) Candi Jinalaya built by Pramodawardhani was Candi Pawon dedicated to King Indra; that (2) Candi Jinamandira was Candi Borobudur completed by Samaratungga; and that (3) Rakai Patapan was another name of King Garung of the Sanjaya and the temple that received a donation from him was Candi Mendut built by King Indra [41].

The Sanjaya and the Sailendra dynasties

Then, how were the Sanjaya and the Sailendra families related? By sorting out the kings’ names in “Balitung’s list”, Dr. N. J. Krom proposed a theory that the main dynasty in Java at that time was Sanjaya, but two persons from the Sailendra had reigned, but a single-dynasty theory in which all kings appearing also in Prasasti Kalasan, Prasasti Kelurak and other inscriptions belonged to one family was proposed, bringing about a lot of arguments[42]. In the 1950s, Dr. de Casparis had extensively studied this problem and launched the two-dynasty theory in which the Sailendra was a powerful family independent from the Sanjaya. [43]

Later, in 1963, a stone inscription, which was suggestive of the origin of the Sailendra was discovered in Sojomerto, Kabupaten Pekalongan [44]. This inscription written in Old Malay and dated 725 AD refereed to a certain adherent of Siwa, named Dapunta Selendra and mentioned that the names of his father, mother and wife were Santanu, Bhadrawati and Sampula, respectively [45]. “Selendra” must be the Malay spelling of Sanscrit “Sailendra”, and the fact that the language used was Old Malay suggested that the founder of the family might have come from Sumatra. Note that the Malay language that formed the basis of the modern Indonesian language originated from the area around the east part of Sumatra and the Strait of Malacca.

While Dr. de Casparis’s two-dynasty theory was monumental, the single-dynasty theory voiced by another famous palaeographer, Dr. Poerbatjaraka, and others still receives support from some researchers as questions are cast on the two-dynasty theory even in recent publications [46]. Personally, I should like to accept Dr. de Casparis’s theory (See Table 1).

The throne of the Sanjaya Kingdom was succeeded, after Rakai Balitung, by Daksa (910–19), Tulodong (919–21), Dyah Wawa (924–8) and Mpu Sindok (928–9). In 928 AD, Mpu Sindok moved the home of the kingdom to the bank of Brantas River in East Java, by abandoning the land of Central Java, and founded the new capital at Medang, the location being assumed to be the area of the present-day Jombang. Thus, the Mataram Kingdom that prospered in Central Java for two centuries disappeared.

King Samaratungga of the Sailendra married Princess Tara of the Sriwijaya Kingdom, which contemporarily flourished in Sumatra (Prasasti Nalanda, undermentioned). In his time, the Sailendra Kingdom had not only ruled the central part of Java Island but had relations with South and Southeast Asia, as a statue of Bodhisattva was presented to Borobudur from Bengal in 782 AD and a high-priest of Ceylon visited Java ten years later on the occasion of the inauguration of a temple [47]. To the question why the Sailendra were able to construct such a stupendous temple as Borobudur at the time of Samaratungga, I would assume that, in addition to the greatness of the king himself, it had largely owed to the wealth of his wife’s country, which was extremely prosperous from sea-trade.

The unification of Sanjaya and Sailendra kingdoms

According to Dr. de Casparis [48], the Sailendra and the Sanjaya kingdoms were virtually united when Pramodawardhani got married to Rakai Pikatan, the then crown prince of Sanjaya, around 832 when her father Samaratungga retired. Prince Balaputradewa, the younger brother of Pramodawardhani, who was still an infant at that time, later insisted the continuation of the Sailendra’s lineage in Java and resisted against his sister and her husband, but eventually moved to the Sriwijaya Kingdom, his mother’s country in Sumatra, and succeeded the throne of the kingdom. Apparently, he seems to have held the title of Sailendra, as it was described in the stone inscription in Nalanda, India, that stated, that “In 860 AD, King Balaputra of Sailendra had built a monastery and King Dewapala of Bengala had donated five villages for its maintenance. Balaputra was the son of Samaragrawira (Samaratungga) who was the grandson of ‘The decoration of the Sailendra’ and his mother, Tara, daughter of Dharmasetu (King of Sriwijaya), who was as beautiful as Goddess Tara.” [49]

Rakai Pikatan ascended to the throne in 838 AD, several years after his marriage with Pramodawardhani, and constructed a group of Hindu temples, represented by Candi Loro Jonggrang, in Prambanan, the details of which having been written in Prasasti Siwagrha erected by his son, Balitung, in 856 AD[50]. That Rakai Pikatan did not exclude Buddhism can be understood from the fact that a fine Buddhist temple, Candi Plaosan, in the neighbourhood, was built by Sri Kahulunan (the royal title of Pramodawardhani) in cooperation with her husband, as recorded in Prasasti Sri Kahulunnan [51].

|

Table 1 The genealogies of the Sanjaya and the Sailendra families (Based on Dr. de Casparis’s Two-Dynasty Theory) |

|

Sanjaya |

Sailendra |

|

Ratu Sanjaya (c. 732–760) | Rakai Panangkaran (c. 760–780) | Rakai Panunggalan (c. 780–800) | Rakai Warak (c. 800–819) | Rakai Garung (c. 819–838) | | | | Rakai Pikatan (c. 838–851) | Rakai Kayuwangi (c. 851–882) | Rakai Balitung (c. 898–910)* |

Selendra (c. 725?)* | Bhanu (c. 752–775) | Vishnu (Dharmatunga) (c. 775–782) | Indra (Sangramadhanamjaya) (c. 782–812) | Samaratungga (c. 8l2–832) (Married to Princess Tara, Sriwijaya)* | Pramodawardhani (married to Rakai Pikatan) Balaputra (moved to Sriwijaya)*

|

|

From: G. E. Hall, A History of South-East Asia 4th Ed. Macmillan Education 1981. ( ): The period of reign in AD, (*): Added by this writer (M. Iguchi) |

As to the reason of the marriage between the Sanjaya’s Prince Pikatan and Sailendra’s Princess Pramodawardhani, we often see such a view that it was for political convenience in that, for instance, “Samaratungga pursued peace and wished to be able to concentrate in the construction of Borobudur”[52]. According to the view of Dr. de Casparis et al. [53], the Sailendra was in a superior position over the Sanjaya and the latter was almost a vassal country at that time. I would like to imagine, romantically, that Pramodawardhani had fallen in love with Pikatan who attended on her father and that the father gave permission for the couple to marry. Pramodawardhani must have been an active woman as her father relied on her support for the building of temples and probably other matters. At least, she must not have been a sort of just graceful and modest princess who obeyed her parents to go marry someone who was not of her taste.

Sima, an enigmatic queen in the Books of Tang

The age when the Sanjaya and the Sailendra prospered in Java corresponds to the era of the Tang Dynasty in China. In the Old Book of Tang (舊唐書, or Old History of the Tang Dynasty) [54], completed in the mid-10th century, there were some accounts on “Ka-ling Country (訶陵國)” situated on an island in the southern sea. The book mentioned the geographical position that “The east is Bali, the west is Dva-pa-tan, the north is Chenla [Cambodia], the south faces ocean” [55], the kingdom’s outline that “they make their castle with hardwood, make multi-storeyed palaces roofed with the bark of hemp-palm. The king sits in it, the whole floor of which is made of ivory”, the culture and customs that “they do not use chopsticks to eat but take foods by fingers. They have letters and good knowledge of calendar. They make wine from the [stem of] palm flower (…)”, and referred to their despatch of embassies in 640, 768, 769, 815 and 818 AD, including monks in 815 AD in particular. In the New Book of Tang (新唐書, or New History of the Tang Dynasty )[56] issued one century later, the following accounts were added. “The seat of the king is in She-po (闍婆). The founder, Ki-yen (吉延), moved to the east from Pa-lu-ka-si (婆露伽斯). In this region there are twenty-four small countries, all of them serve as vassals. (…) On the summer-solstice, a gnomon of 8 feet high, if erected vertically, casts a shadow of 2 feet 4 inches (2.4 feet) long on the south side. (…) In Shangyuan Period [674–5 AD], the country people assigned a female, named Sima (悉莫), to the throne. Her rule was just and things dropped on the road were not taken up. (…)” The name of the country, Ka-ling, alternatively pronounced as Ho-ling, also appeared in Buddhism books, one example being Legends of the teaching of Secret Mandala by Konghai, in which the author received a lecture from Huiguo together with a monk from Kalinga named “Benhong” .

The old and the new books of Tang have been of interest to scholars ever since the late 19th century [57], and what country corresponded to Ka-ling and “who was Queen Sima and who was Ki-yen who moved the capital to the east” became big issues. By applying “Ka-ling” to Kalinga, the country’s association with India was argued, but it was no more than a speculation. As to the geographical position, it was pointed out that the incidental angle of the sunbeam, written in the New Book of Tang, indicated 6°8' N that did not fall in Java Island[58]. Today, however, the capital of Ka-ling (or Kalinga) is considered to have existed somewhere around the present-day Semarang, or Pekalongan (where the Prasasti Sojomerto was discovered), or Keling Village in Kabupaten Jepara [59].

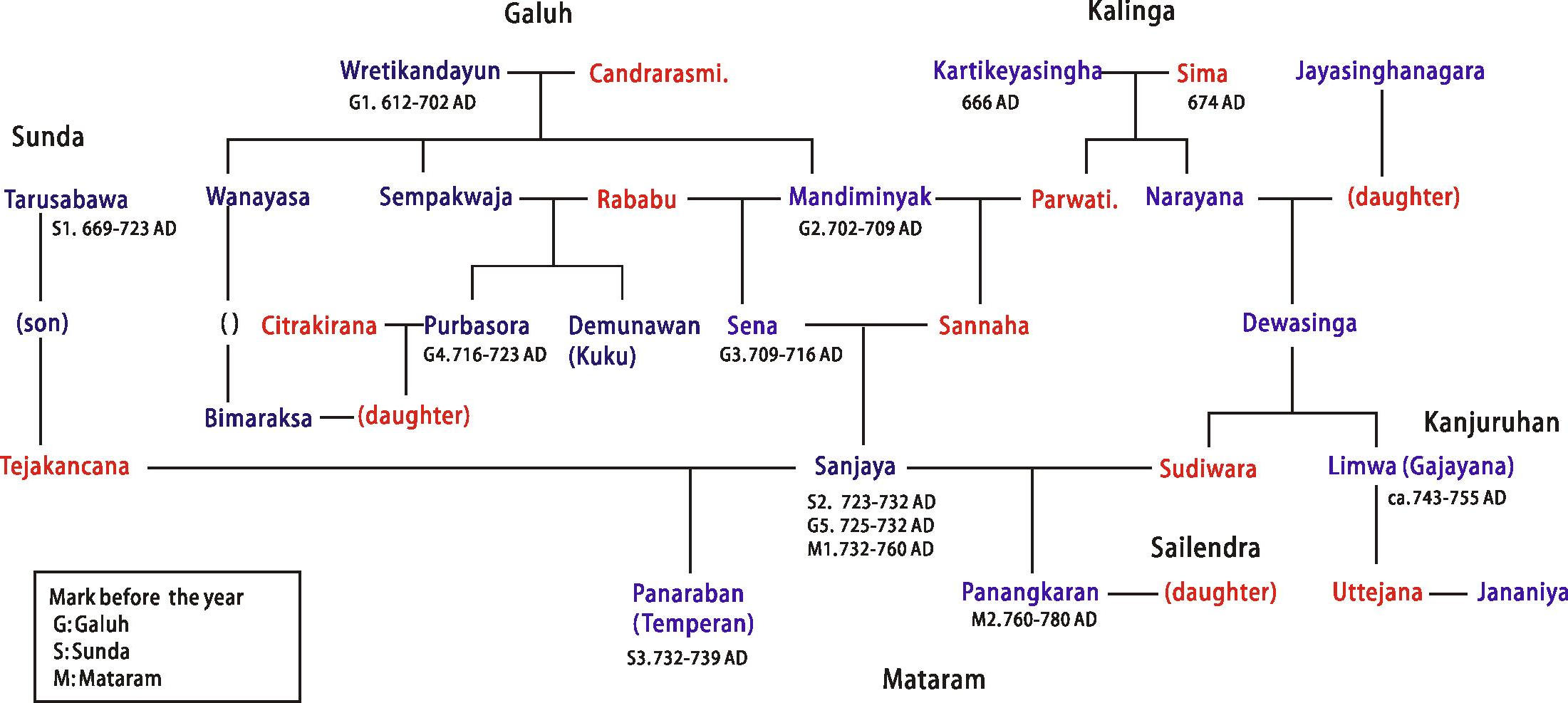

The lineage of the Sima, the Sanjaya and other families found in history books written in West Java

I was aware of the fact that Sanjaya was a person who moved from Galuh Kingdom, in West Java, to Central Java, which I had read somewhere. Looking again into the Sejarah Bogor (History of Bogor) by Prof. Saleh Danasasmita[60], I found some accounts on the relationship between the Sanjaya’s lineage and the Kalinga, which was as follows.

“King Mandiminyak, the 5th king of Galuh Kingdom, married Parwati, a daughter of Queen Sima of Kalinga. He had a son named Sanna. Between Sanna and Sannaha, a granddaughter of Sima, Sanjaya was born. Sanjaya was adopted as a son-in-law by his father’s friend, Tarusabawa, the first king of the Sunda kingdom, married to the latter’s daughter, Tejakancana, and became the 2nd king of Sunda. His real father, Sanna, was ousted from the throne in 716 AD by his half-brother (same father and different mother) and fled to Kalinga, the country of his wife’s grandmother. Although Sanjaya had revenged on his father’s sworn enemy and simultaneously assumed the crown of Galuh (the 5th), he abdicated the throne in favour of his son, Tamperan (also called Rakeyan Panaraban) in 723 AD and became the King of North Kalinga, as a rightful successor. He married Sudiwara, a daughter of King Dewasinga of South Kalinga (Bumi Sambara) and Panangkaran was born between them, etc.”

Unfortunately, the source of the documents was not given for this citation. I have remembered a book entitled Pustaka rajya rajya i bhumi Nusantara (meaning,The Book of Kings in the Land of Archipelago. Hereinafter, The Book of Kings, for short) [61], compiled in the 18th century in West Java, and took up the file of its photocopy from my bookshelf. To my surprise, many facts about the Sanjaya family and its relation to Kalinga were written in it in significant detail. Let me summarise the corresponding part and translate from Indonesian language, because no direct reference to this book has been found in books and articles that I have surveyed.

“In Sumatra, Sriwijaya Kingdom had gained the hegemony by 613 Saka (691/692 AD) and was dominant over other countries. While Sriwijaya had a pact with Sunda Kingdom of West Java, signed between the former’s King Jayanasa and the latter’s King Tarusabawa in 607 Saka (686 AD) and ambassadors were exchanged between them, they were always envious of the Keling Kingdom, which was very fertile and rich.

“In the Keling Kingdom, Prabu Kartikeyasingha had died in Mt. Mahameru [62] and his wife, Dewi Sima was on the throne. The kingdom had a friendly relationship with China, having sent an embassy with priests and astrologers in 570 Saka (648/649 AD) during the reign of King Kartikeyasingha. and another embassy in 578 Saka (666/667 AD). Before then, Kartikeyasingha’s father had sent embassies to China in 554 Saka (652/653 AD) and 562 Saka (640/641 AD). The founder of the Keling originated from the south Bharata (India).

“Dewi Sima was an elegant and charming woman unrivalled in Java, a perfect beauty like a heavenly maiden. Sri Jayanasa of Sriwijaya had fallen in love with Sima, but his love was not realised, because Sima disliked him to such an extent that she would kill herself, if marrying the man was inevitable. Notwithstanding, Jayanasa persistently approached and distressed Sima. Apart from her hatred, the religions were different between the kings of Sriwijaya and Java, as they followed the Mahayana Buddhism and the Saura [a fact of Hinduism], respectively. It was also known that Sriwijaya had plundered the gold and diamonds from Melayu [a kingdom in Sumatra] whom they had subjugated.

“In 608 Saka (686/697 AD), the king of Sriwijaya attacked Java, but in vain, because the Chinese Empire, Bakulampra Kingdom, Hujung Mendini Kingdom and other Indian countries supported Java. Then, the king of Sriwijaya ordered Javanese merchant ships berthed in the ports of Palembang and Bangka to return home, robbing their properties. In addition, the king gave orders to pirates to attack the Javanese on the sea.

“Sunda Kingdom was not agreeable with the ambition of the king of Sriwijaya and asked him for calmness and reconsideration.

“According to the history, Sriwijaya Kingdom conquered the regional kingdom of Sanghyang Hujung and created a sanctuary there.

“Below is the narration of a great poet. Dewi Sima and Prabu Kartikeyasingha had children, two of them being Dewi Parwati (daughter) and Nalayana (son). Dewi Parwati married to Sang Mandiminyak, the king of Galuh, and they had a daughter named Dewi Sannaha. Mandiminyak married also Pwah Rababu and had a son named Sang Senna (alias Sang Bratasennawa). Senna married Sannaha and a boy named Rakryan Sanjaya was born between them. Senna was ousted from the throne by Purbasora.

“Sanjaya conquered King Purbasora of Galuh and became the king of Galuh. Sanjaya had already ruled Indraprahasta Kingdom [the present-day Cirebon]. It was because Indraprahasta was supporting Galuh, as Purbasora’s wife was a daughter of the Indraprahasta, and, in fact, the army that defeated King Senna was the troops of Indraprahasta, led by Purbasora himself. By the assault of Sanjaya, the king of Indraprahasta, Purbasora and his wife, astrologers, ministers and officers were killed.

“Moreover, Sanjaya advanced his army towards the east and subjugated many kingdoms in Central and East Java. Then, he attacked many countries in Sumatra, including Melayu, Sriwijaya and Barus. After then, he turned to the north. Sanjaya’s campaign lasted for three years.

“In 645 Saka (732/733 AD), Sanjaya became the king of Medang in the Soil of Mataram (Medang i bhumi Mataram). Sanjaya was succeeded by his son, Panangkarana. His wife was a woman of the Selendra. Then, the Selendra became a powerful kingdom. The land of Central Java was divided and the northern and southern parts became the territories of the Sanjaya and the Selendra, respectively.”

The year of Queen Sima’s coronation, 674/675 AD exactly coincides with the Shangyuan Period (674–5) recorded in the New Book of Tang. The years of sending embassies to China in the West Java chronicle do not agree with those in the Old Book of Tang, but I would refrain from arguing the reason, rather conjecture that the former document, edited in the later century on the basis of fragmental records and oral traditions, had inevitable errors. That “Keling”, “Selendra” and “Senna” denote the same words as Kalinga, Sailendra and Sanna, respectively, is undoubtful.The fact that the parents of Sanjaya, Sanna and Sannaha, were both son and daughter of the same father, Mandiminyak, born from different mothers, Rababu and Parwati, is noteworthy. Although a marriage between a half-brother and a half-sister is hardly thinkable nowadays, from both ethic and genetic viewpoints, some cases were there in old days also in Japan and elsewhere in the world [63].

Next, I wished to check the famous Carita Parahiyangan ( The Story of Parahiyangan), written on lontar strips around the 16th century by an anonymous author, but the text I had obtained by courtesy of an authority through my friend in Bandung was still in Old Sundanese, which was hardly readable by myself. Then, I asked a student of Sundanese Literature Department of Pajajaran University to translate it into modern Indonesian, and found some accounts on the life of Sena (Sanna), such as follows [64]:

“Pwah Rababu, a daughter of the Lord of Kendan had once a coitus with Lord Makadria, as her father told, but later married to Rahiang Sempakwaja, who became the Governor of Galungun, and gave birth to two sons, Purbasora and Demunawan. One day, when she went to Galuh, she was seduced by Mandiminyak, the youngest brother of her husband, who had succeeded the throne of Galuh, and after months delivered a male baby who was named Salah. Having been told by her husband to give the baby away to Mandiminyak, she took him to Galuh. Mandiminyak said, “Oh, this is my son!”, but ordered his retainer to put the baby in a vase and carried it to the field. When the retainer left the vase and returned, a sign shone from the field to the sky, but the baby was still alive. He was renamed Sang Sena. Sena succeeded the throne of Galuh, after his father, but seven years later he was expelled by Purbasora and fled to Mt. Merapi [Central Java].”

From this description, it has become evident that Purbasora and Sanna (Sena) were half-brothers from different mothers and that the expatriation of the latter by the former was a sort of family discord. With regard to the transfer of power from Sanna to Sanjaya, the clause in Prasasti Canggal that it was done “not directly from King Sanna but through the king’s elder sister, Sannaha” was quite ambiguous, but now it could be alternatively interpreted as “through the king’s consort, Sannaha” or “through Sanjaya’s mother, Sannaha”. It might have been probable that the status of Sannaha who was the legitimate child from the legal wife of Mandiminyak was higher than that of Sanna who was an illegitimate child from the wife of Mandiminyak’s brother.

Among the facts that Sanjaya conquered many countries in Java Island as well as Melayu and China (?), also written in Carita Parahiyangan, a line that he “waged war against Keling and defeated Sang Sriwijaya” (Sang=a respectful title) has provoked a thought in my mind. Although Kalinga had rejected the approach of Sriwijaya in the era of Queen Sima (according to The Book of Kings), was Kalinga under the rule of Sriwijaya at the time of the queen’s great-grandchild?

Although Sanjaya was a great king in West Java, Carita Parahiyangan mentioned that he was estranged by Kuku (alias Seuweukarma), his father’s half-brother and Purbasora’s younger brother, who became the king of Kuningan, as well as other local rulers, as a killer of a family member, suggesting that this could be the major reason of Sanjaya’s move to Central Java.

The description in The Book of Kings that “Panangkaran (the son of Sanjaya who was born after his father’s move to Central Java) took a woman of the Sailendra to wife and, then, the Sailendra became a powerful kingdom” told that a marital relationship was formed between the two families, although who the woman was was not written. This could be the reason, or one of the reasons, why Panangkaran was so cooperative with the Sailendra in the construction and the maintenance of Buddhist temples and probably in other matters.

The phrase, “King of Medang in the Soil of Mataram (Rajya Medang i bhumi Mataram)” in The Book of Kings has appeared on some stone monuments, giving the Mataram Kingdom founded by Sanjaya another name, “Medang Kingdom”. Because later kings occasionally moved their capital (e.g. Rakai Pikatan to Mamrati and Dyah Balitung to Poh Pitu), however, Medang Kingdom may be more precise to be applied for the whole period of the Sanjaya Dynasty[65].

Another description in the same book that the area of Central Java was divided into the northern and southern parts and shared by the Sanjaya and the Sailendra, respectively, is probably noteworthy. Whether this book was refereed or not is unknown; this demarcation is written in general books and textbooks for secondary high-school in Indonesia [66], along with the fact that “while Candi Gedung Songo on the mountainside of Ungaran in the northern part of Central Java and groups of candis in Dieng Plateau were built by the Sanjaya, many candis in the Kedu Basin and Prambanan Plain were built by the Sailendra”. One remarkable exception is a group of candis in Prambanan, represented by Candi Lolo Jonggrang, which is comparable with Candi Borobudur in its scale and magnificence (to be undermentioned).

The name of Sudiwara, daughter of the king of South Kalinga, Dewasinga, whom Sanjaya took as his wife in Central Java, mentioned in The History of Bogor, was found in a stone inscription, dated 760 AD, discovered in Dinoyo near the present-day Malang. In addition to the fact that “the centre of the kingdom existed in Kanjuruhan”, it was written that “once, there was a just and powerful king named Dewasinga. This monument is to commemorate the construction of a temple, by his son, Gajayana, to enshrine the new statue of Agastya to replace the old rotten piece”.[67]

The fact that Gajayana had established himself in this district must correspond to the “transfer of the kingdom” written in the New Book of Tang, and Gajayana himself is regarded as Ki-yen. The fact that the two events, i.e. the transfer of the kingdom by Ki-yen in the late 8th century and the enthronement of Queen Sima in the late 7th century, are written in chronologically reverse order in the New Book of Tang must be heeded, as it is generally said the records in this New Book are frequently confused, while those in the Old Book of Tang are not.

Extracting the names of kings, consorts, princes and princesses appearing in above documents and adding some more names found in some articles[68] on Babad Galuh (Galuh Chronicle), I have drawn a genealogical chart that includes the families of Sanjaya, Queen Sima and others.

The reason of Gajayana’s move to East Java has not been concluded. If one was to assume that he was expelled from Central Java by Sanjaya, the husband of his sister, Sudiwara, the question of why their relationship was so bad has to be answered. I would prefer to think that, in such a circumstance that the Buddhist Sailendra gained power and Sanjaya’s son, Panangkaran, was the supporter of Buddhism, Gajayana had decided to explore a new land for Hinduism in East Java.From the New Book of Tang, Kalinga seems to have continually sent ambassadors to China after Gajayana’s move to East Java. As to the question why the same book lacked accounts on the Sanjaya and the Sailendra dynasties, I can only speculate that the Chinese had no information, having received no diplomatic mission. In any event I would assume that the existence of Kalinga in Central Java had ended by the move to the east by Gajayana.

Let us stop the review of the difficult history and return to Borobudur. From the records of stone inscriptions, the construction of Borobudur is considered to have required forty-two years, ever since it was commenced by King Indra in 782 and completed by King Samaratungga in 824. Although priests and architects might have been invited from Sriwijaya and India, the majority of inhabitants at that time would have been Javanese as inferred from the sculptures that ornamented the temple. The features of Buddha statues looks to have portrayed the gentle, round faces of Javanese men, and the appearance and gesture of people on the reliefs depicted their characteristics. In Journeys to Java, Marquis Tokugawa cited a comment of Mr. Hidenosuke Miura, then an assistant professor, from Tokyo Fine Art School, who he incidentally met there, “It is interesting, isn’t it? The life of Javanese people depicted here of more than one thousand years ago is not so much different from the life of today’s Javanese.”

Prof. Miura’s Javanese Buddhist Remains – Boroboedoer [69], published in 1925, with photographs of all reliefs and statues of Borobudur, is regarded as a rival of the aforementioned book of Dr. Krom as complete image recording of Borobudur. When I saw the book in the Tokugawa Reimeikai Library, I was much surprised by the sharpness of the reliefs in the photographs taken only ten years after the temple’s first restoration. When such photographs are compared with the real sculptures that we see today, we can notice how seriously erosion has progressed on the stone surfaces after exposure to air. The condition looks to have worsened during the last quarter-century, ever since I saw them for the first time, as they have suffered from acid rain. It is said that the whole Borobudur temple was originally covered with plaster and coloured. A humble researcher of polymer chemistry, I wondered whether it could not be possible to protect them with a thin layer of some silicone varnish even from now. When I had the honour of accompanying the late Mr. Yoshinobu Tokugawa, an expert of art history and archaeology, to Borobudur, he told me, “It is a difficult issue as if you did so would mean that you would spoil the object. One could say the fact that the ruins were excavated itself was the beginning of destruction!” I had also thought that it could not be impossible for modern technology to put a huge roof to cover the whole temple, as was done for the Wimbledon court and some baseball fields, but it would not match the original concept conceived by King Indra and Rev. Gunadharma twelve hundred years ago. The making of replicas of historical relics is a common practice, but it can be only applied to some limited number of components, such as statues and reliefs, not to the whole gigantic monument. After all, I thought that photographs, especially those taken in early days, would be of immense value as records for the future. With the current imaging technology, to create three-dimensional images of all statues and reliefs or the image of the whole of Borobudur would not be difficult.

There was a tragic episode in the book of Prof. Miura in that “To publish his new theory, the manuscript, the photographic plates and other materials were brought to a printing company in Kanda-Mitoshiro Street [in Tokyo] and the book was just ready to be turned to the binding process, when the Great Kwanto Earthquake [1 September 1923] occurred and everything was reduced to ash.[70]” Probably, a backup copy of the manuscript must have been safe in a different place.It is said that the social structure in Java around the 8th–10th centuries was not of such feudalistic type as in Western Europe in which the land and the military service were interlinked. In Java, in exchange for receiving services, the kings gave lands to religious organisations, high officials and royal family members, and granted rights to collect taxes and to operate industrial and commercial activities. No slave system had existed and farmers had a duty to serve for a certain number of days in agricultural off-seasons. Although they were often recruited as non-skilled labourers for the construction of temples, they would have served themselves with a pious mind. Professional architects and sculptors who were indispensable for the construction of Borobudur and other temples were probably exempted from other duties and formed artisan groups [71].

Nevertheless, whether the whole design of Borobudur was imaged and drafted up by the legendary architect, Gunadharma, alone is an open question, while, if it were today, a project team of one hundred selected members of Buddhism scholars, architects and artists would be organised and several thousand sheets of drawings would be prepared with full use of computer graphics. At that time when even a sheet of paper was yet to be produced [72], it is hard to imagine how the master architect was able to notify the details of his design to his engineers and artists. The generation of his staff and labourers must have altered during the construction period of some forty years. In Europe, there are many churches and cathedrals that were built in several hundred-year periods, but their construction is considered to have been the continuation of much simpler works compared with that of Borobudur.

As a Buddhist monument, Dunghuang (敦煌) in China is much better known in Japan, apparently because NHK has spent an enormous amount of money and persistently broadcast the film, apart from a famous novel by Yasushi Inoue [73] and fine sketches by Ikuo Hirayama[74]. Statues and paintings of Buddha installed in several thousand caves of Dunghuang from the 4th to the 11th century are no doubt valuable for the study on the diffusion of Buddhism on the northern route, but all those relics are the kind of things that had been arbitrarily and sporadically brought there by unspecified people. When I had a chance to visit Dunghuang, I was impressed that, in terms of the artistic value, the remains are inferior to the temple of Borobudur, which had been built according to a single concept at one time.

Before visiting Prambanan, let me report on the situation of Dieng Plateau. It was twenty years ago that I went there for the first time. From Yogyakarta, my party took a route to the north to Tumanggung and, by turning to the left, passed the col between two mountains, Sumbing and Sundro, which both showed their beautiful conical forms. We stopped at Wonosowo and stayed overnight in a small losmen (tavern). It was cool but so cold on the mountainside town of 2,000-metre elevation from the sea-level that I had to request a pail of hot water to take a mandi (shower). Next morning, we drove off again to Dieng Plateau located twenty kilometres to the north, above 200 metres, on a winding road that was much steeper and sharper than that over the Hakone Pass in Japan or probably the famous Hanguguan in China. The hills on both sides were well cultivated and I was told that various vegetables grown there were transported far away to the market of Yogyakarta. There were some greenhouses to grow mushrooms, too. While I was thinking over the efforts of the authorities who had constructed this metallised road a hundred years ago and the hard labour of farmers, the car brought us to Dieng of 2,200-metre elevation from the sea-level. The circumstance of the tableland of 1 kilometre east–west and 1.5 kilometres north–south with gentle undulations was dreary, where the vegetation was quite shabby, some cypress trees with dark-green needles only on their top parts standing to and fro. I was told that to see morning frost, or even thin ice, was not rare in dry seasons. In the middle of the plateau was a small lake, which was turbid with a white colour produced by sulphur, reminding me that the place was an old caldera. On a small hill was an experimental geothermal power station, which emitted white steam together with the smell of sulphur. Just for information, Indonesia is now the second leading geothermal-power-producing country after the United States of America, while the abundant geothermal resources are little used in Japan due to various regulations.

Next day, we first visited several Hindu temples, named Candi Arjuna, Candi Semar, etc., named in a later century, located in the northern part of the plateau. They were masonry works with a basement of some ten metres square and ten to fifteen metres tall, the roofs of which had not been restored. The inside of the niches were empty, as statues had been removed to some museums. They were said to have been constructed around 670–730 AD in the early period of the Sanjaya Dynasty, and the carvings on the walls were far less sophisticated than those of candis built later in Kedu Basin and Prambanan Plain. Candi Sembadra in the western part and Candi Bima in the southern part of the tableland were said to be the constructions built in the beginning of the 13th century, suggesting that Hinduism was maintained by some local lord after the move of the Sanjaya Dynasty to East Java, although the make of those candis was simple.

Walking around Dieng Plateau, I really wondered why ancient people had chosen this remote highland as the site of their worship, by providing footpaths with several thousand steps from the foot, from four directions. The name of the place, Dieng, was derived from the Sanskrit Dihyang, which meant the abode of the gods. In an old Javanese manuscript,Tantu Panggelaran [75], was told a mythical story, which follows.

A myth on the birth of Java Island

“Bhatara Guru [Lord Shiva] created the island of Java together with his wife, Bhatari Parameswari [Durga] and provided Mount Dihyang [Dieng], but the island was drifting on the sea. Shiva ordered the gods to move the sacred mountain, Mahameru, from Jambudipa [India] and put it on Java as a weight to stabilise it. Visnu and Brahma transformed themselves into a long serpent and a huge turtle, respectively, and the latter carried Mount Mahameru on his back, while the former put himself around to bind it. When Mahameru was placed on the western part of Java, the island was unbalanced and tilted. During the process of moving Mahameru eastwards, the mountain broke apart and six more mountains, i.e, Kantong, Wilis, Kampud, Kawi, Arjuna, and Kemukus, were formed along the route.”

Mt. Mahameru, alternatively called Mt. Semeru, located to the east of the present-day Malang as the highest peak in Java (3,666 m), is still a sacred mountain, especially for Tenggerese, an ethnic group who live around the area and have worshipped Shiva ever since the Majapahit time. Note that Semeru is equivalent to the Chinese Xumishan (須彌山) or the Japanese Miyaukau-zan (or Myōkō-zan, 妙高山). When I spoke about Mt. Semeru to my old friend, a textile engineer and scholar of Japanese history as well as a mountaineer who had conquered many high peaks in the world, he pointed out that Semeru would lead to “Sumera”, an archaic Japanese word for emperor. According to his theory, the Sanskrit word, “Semeru”, for “the supreme being”, originating in ancient Indian philosophy prior to the birth of Hinduism and Buddhism, must have been introduced in Japan in the unknown past and applied to “emperor”.

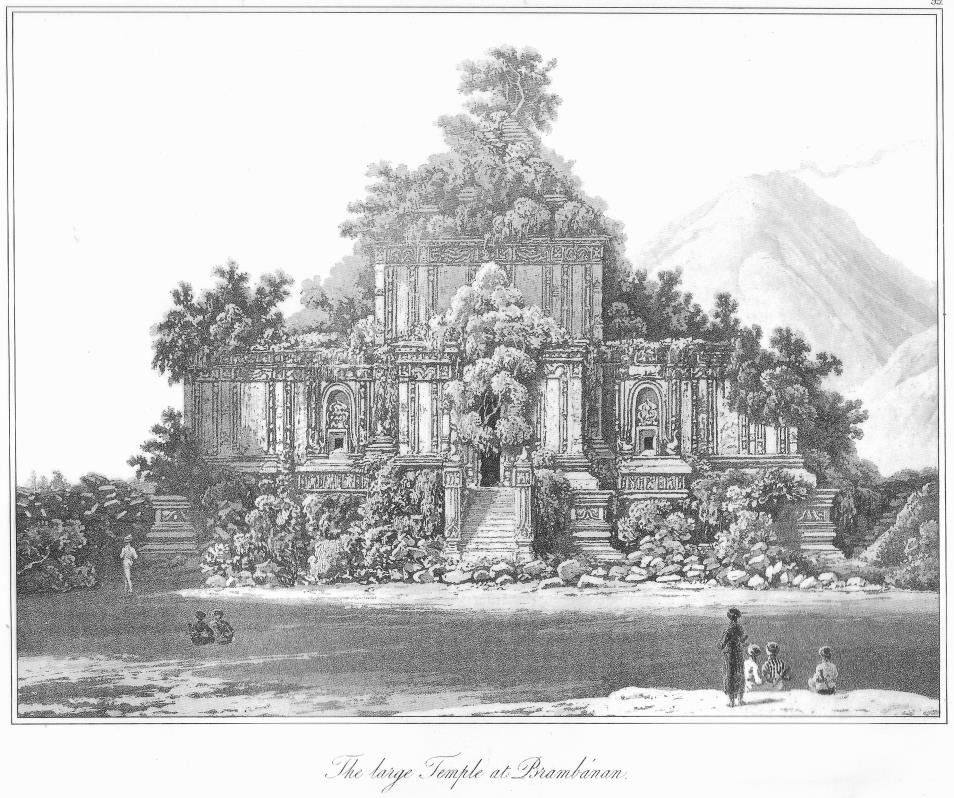

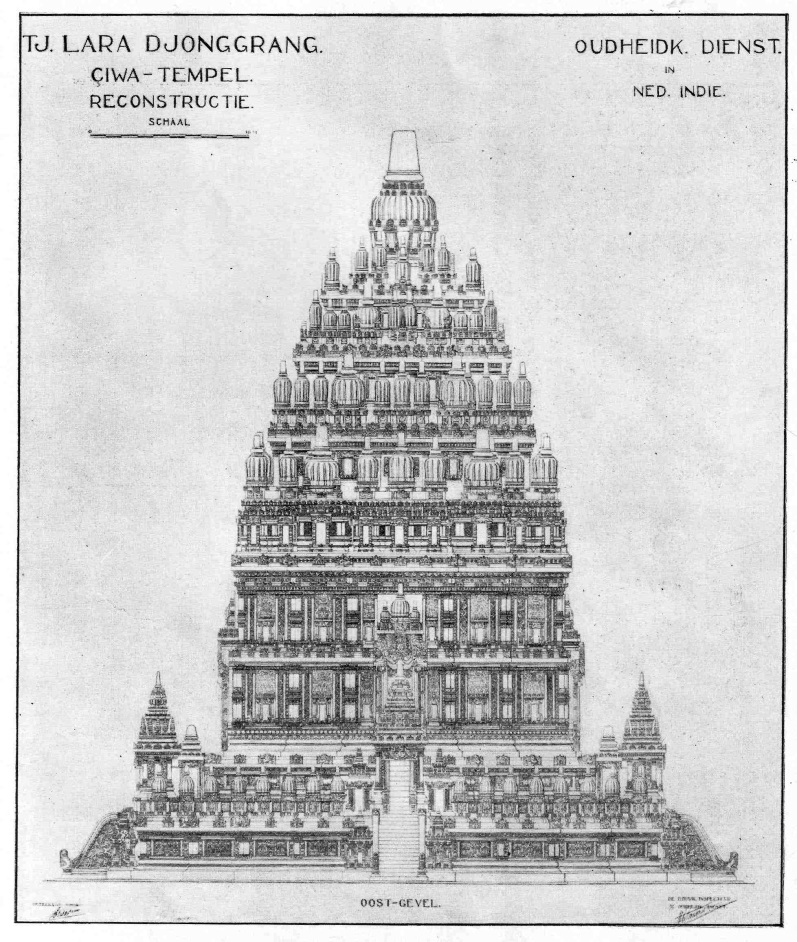

Now let us go to Prambanan. If one takes the main road from Yogyakarta towards Solo for twenty kilometres in an east by northeast direction, a group of Candi Loro Jonggrang appears on the left-hand side like towers. As mentioned above, these temples built in the mid-9th century had been embedded under the soil and vegetation, like Borobudur, until their existence was reported in 1733 by C. A. Lons of VOC. Although Baron van Imhoff, who served as the governor-general of the Dutch East Indies (1743–50) and known as the founder of the Buitenzorg estate, had once visited there in the mid-18th century, the first cleaning operation was conducted much later in 1807 by Ir. H. C. Cornelis under Governor-General Engelveld. Stamford Raffles who saw the ruins six years later wrote under the heading of ‘Chandi’ Lolo Jongglang (or Temples of Lolo Jonggrang):

“These lie directly in front (north) of the village of Brambanan and about two hundred and fifty yards from the road, whence they are visible, in the form of large hillocks of fallen masses of stone, surmounted, and in some instances covered, with a profusion of trees and herbage of all descriptions. In the present dilapidated state of these venerable buildings, I found it very difficult to obtain a correct plan or description of their original disposition, extent, or even of their number and figure…”[76]

|

The big temple at Prambanan Reproduced from: Antiquarian, Architectural, and Landscape Illustrations of the History of Java 1844 (John Bastin (preface), Plates to Raffles's History of Java, Oxford University Press, 1989). This sketch was made by Ir. H. C. Cornelis who conducted the cleaning operation in 1807. |