Chapter 4

Pajajaran Kingdom – The Spiritual Home of Sundanese People

Batu Tulis, a precious stone monument

On the hill of Batu Tulis overlooking Cisadane (Sadane River), two kilometres south of the present city centre of Bogor, is found an old relic called “Prasasti Batu Tulis”, or “Batu Tulis” for short, which is different from those stone monuments of Tarumanagara. As “batu” and “tulis” mean “stone” and “writing”, respectively, in the local language, “Batu Tulis” denotes a stone inscription, giving its own name to the surrounding area.

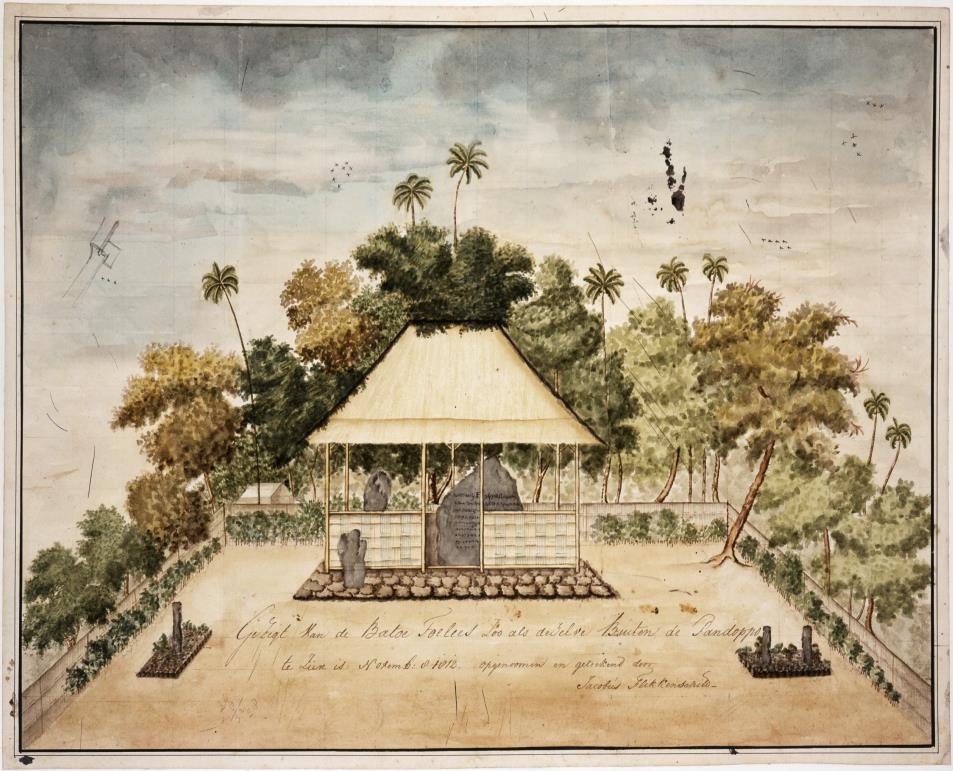

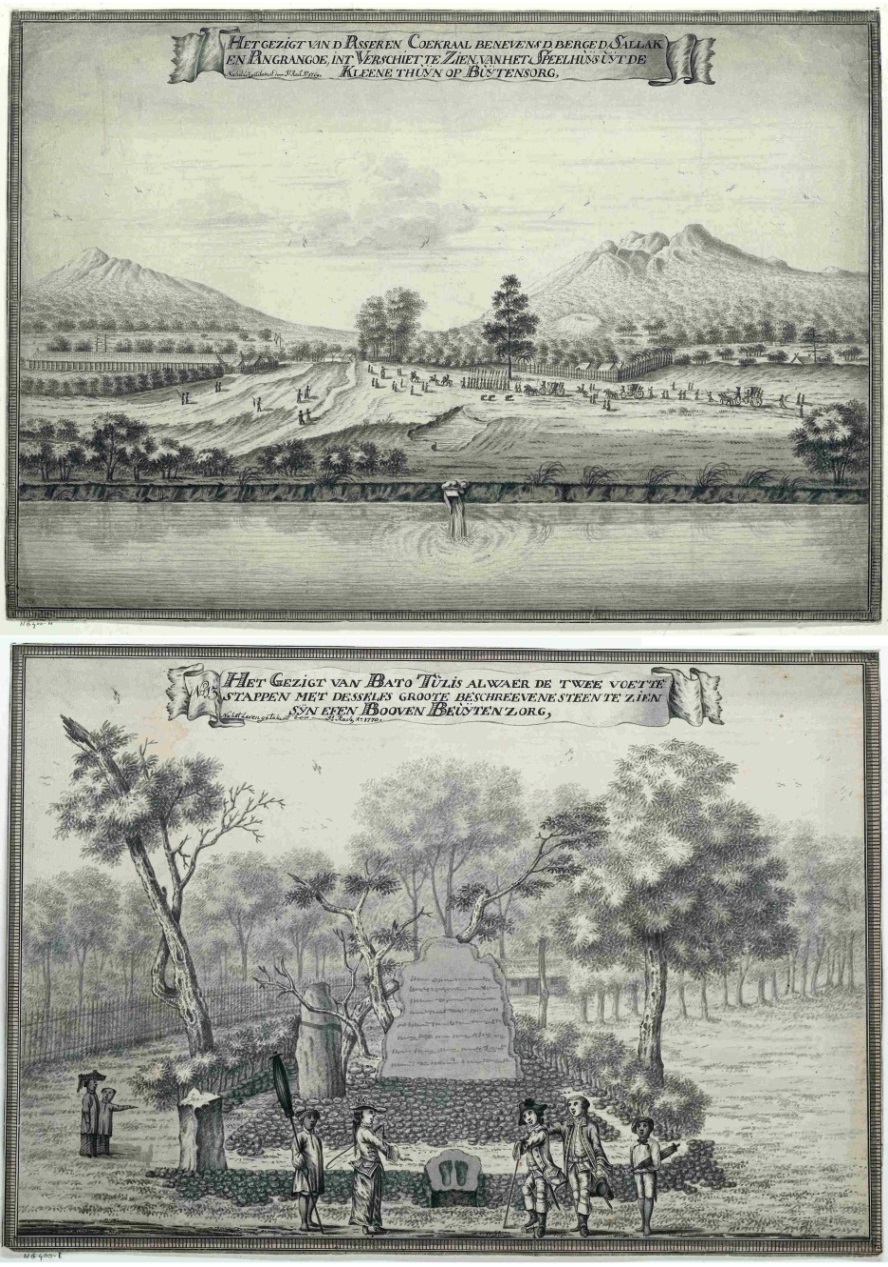

|

A shelter at Batoe Toelees containing an inscribed slab by Jacobus Flikkenschild 1812. British Museum: Number 1939,0311,0.5.37. Reproduced by permission of the Museum. Flikkenschild graduated from the naval school of Semarang, became an assistant of the famous draftsman, H. C. Cornelius, and came to Buitenzorg by order of Stamford Raffles, the then Lieutenant Governor of Java (Leo Haks, Guus Maris,Lexicon of Foreign Artists Who Visualized Indonesia [1600– 1950], Archipelago Press, Singapore 2000). |

The existence of this monument had long been known also to Europeans and, according to a paper of a famous palaeographer, Dr. Poerbatijaraka [1], it was reported already in 1690 by a patrol of VOC (the Dutch United East India Company), but it was only after the late 19th century that archaeological research started [2]. The monument consisted of four pieces of stone placed in a 17×15 metre plot, and on the largest one in the middle was inscribed a nine-line note in Sunda-Kuno characters, with the following meaning:

|

May we be saved! This is the memorial of the late king. He was crowned with the title of Prabu Guru Dewataprana, and was crowned [again] with the title of Sri Baduga Maharaja, His Majesty the Ratu Dewata, as the controller in Pakuan Pajajaran. He was the one that built the [defensive] moat of Pakuan, He is the son of Rahyang Niskala who had been interred at Gunatiga, and the grandson of Rahyang Niskala Wastu Kancana who had been interred at Nusa Larang. It was he who made it possible for vehicles to pass mountains, who built the mansion, who made Samida forest, made the holy Talaga Rena Mahawijaya Lake. Yes, he was the person [who accomplished all of them]. [The year of] five-five-four-one Saka [1455] [3] . |

According to Carita Parahiyangan [4] , which was written at the end of the 16th century in Cirebon, Sri Baduga Maharaja was a great king who established the Pajajaran Kingdom and ruled the whole area of West Java with its capital at Pakuan (the present-day Bogor) for such a long period as 1482–1521 [5]. Before writing about the kingdom itself, which existed for almost a century until the capital fell to the hand of Moslems in 1579, let us briefly review the history of West Java.

|

The Batu Tulis stone monument. Photographed with permission of the caretaker by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

Brief review of West Java’s history

According to Pustaka rajya rajya i bhumi Nusantara ( The Book of Kings in the land of Archipelago), compiled in the late 17th century[6], the first kingdom that ever existed in West Java was Salakanagara, which rose in the 2nd century. Tarumanagara founded in 358 AD by Jayasinghawarman was most prosperous during the reign of the 3rd king, Purnawarman (395–434 AD), as inferred from several pieces of contemporary stone monuments, which remain to date. Although the seat of the king was supposedly located around the present-day Bogor where several stone monuments were found [7], he is said to have built a new city, “Sundapura”, near the coast for the convenience of trade, soon after his coronation in 397. This is the first appearance of the word “Sunda”, in the literature, with which the land and the people in this area are called Tanah Sunda (the Land of Sunda) and Orang Sunda (Sundanese People). The term was also applied for the Strait of Sunda (between Java and Sumatra Islands) and the Sunda Islands (archipelago from Sumatra eastward).

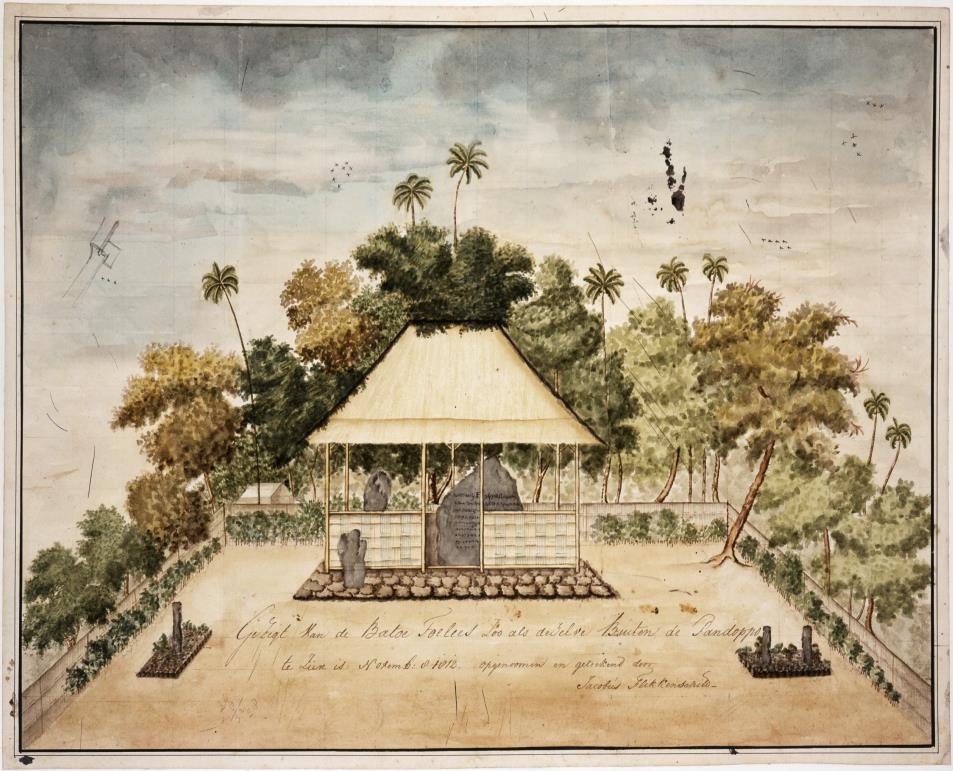

| The chronology of kingdoms in West Java (Data from: Saleh Danasasmita, Sejarah Bogor, Pemerintah Daerah Kotamadya DT II Bogor, 1983). |

During the reign of Purnawarman, the territory of the kingdom ranged from Rajatapura (the bank of Ciujung) to the west and Purwalingga (the present-day Purbolinggo) or Cipamali (Breves River) in Central Java to the east, with forty-eight vassal kingdoms. In 526 AD, Manikmaya, a son-in-law of the 7th king, Suryawarman, erected a small new kingdom at Kendan near the present-day Cicalengka, east of Bandung, and in 612 AD, Wretikandayun, a great-grandson of Manikmaya moved the capital further east to Galuh, near the present-day Ciamis (the royal line continued up to 852 AD). For Kendan-Galuh kingdom, it ought to be noted that the 8th king, Sanjaya Harisdarma, is alleged to have moved to Central Java in 716 AD to become the founder of the Sanjaya Kingdom, also referred to as Mataram.

Tarumanagara itself was weakened in the middle of the 7th century, attacked by the strong Sriwijaya Kingdom in Sumatra. In 669 AD, the 12th King Linggawarman devolved the property of the kingdom to his son-in-law, Linggawarman, who founded the Sunda Kingdom and ruled the area.

The regal power of the Galuh Kingdom, which occupied the area to the east of Citarum River, was taken over by the Sunda Kingdom in the middle of the 9th century when a princess of the former married Rakeyan Wuwus (or Prabu Gajah Kulon) of the latter, but the princess's brother succeeded the throne under the name of Prabu Damaraksa Buana and became the 9th king of Sunda. During the following 300 years, the seat of the king was frequently moved from the west to the east, or vice versa. It is said that it was during this period that the different customs of the two regional, or sub-ethnic groups, merged[8].

In 1333 AD, Linggawisesa, a son-in-law of the 26th Sundanese king, Linggadewata, founded a new kingdom in Kawali, not far from Galuh in the eastern part of West Java. After then, the kings of Kawali concurrently held the kingship of Sunda for over one century, as the latter was inferior, until 1482 when, as mentioned above, Ratu Jayadewata of Kawali unified the two kingdoms and founded the Pajajaran Kingdom under the name of Sri Baduga Maharaja with its capital at Pakuan.

|

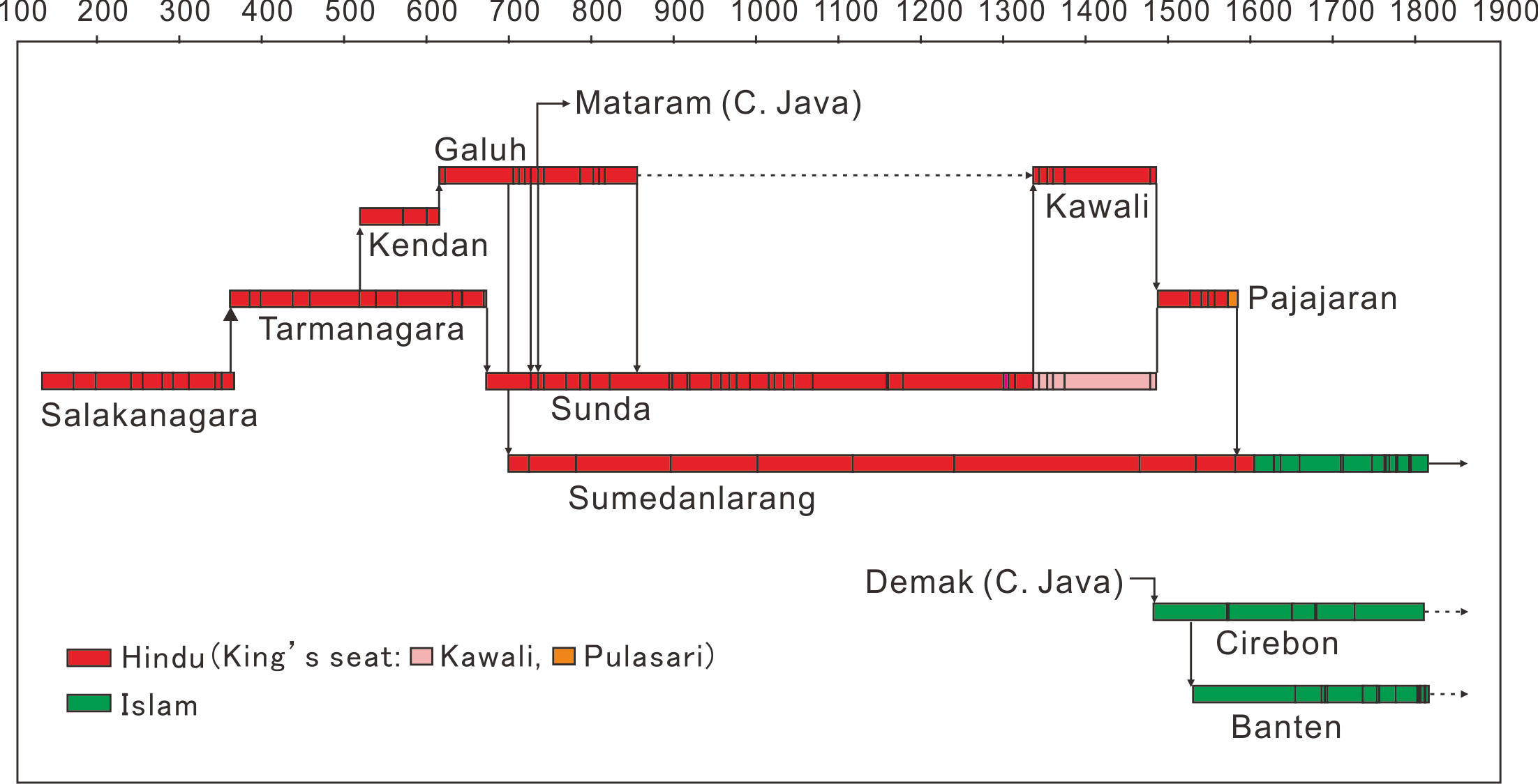

West Java of Sunda/Pajajaran Era (Prepared based on Atlas Indonesia dan Dunia, PT Punbina, Jakarta 1985). |

Although documents that describe the situation of Sunda are rare, an account is found in Zhu fan zhi (諸蕃志, Accounts of Various Barbarians) compiled by Zhao Rugua in 1225 in the South Sung Period China:

|

In Sunda, there is a harbor of sixty feet depth to which ships frequent. On both sides are houses, of people who work for farming, built on piles with wood, roofed with palm leaves and floored with wood board and walled with bamboo panel. Both man and woman are naked, wrapping a cloth around their waist and cutting their hair in a half-inch. In mountains, they produce pepper which is better than that in Tuban. In the land, they grow white gourds, sugar cane, gourds and aubergines. No just officials are there, robbers are rampant, so that foreign merchants rarely come. [9] |

In this translation, a Chinese word, 籐篾, which may literally mean a rattan strip, has been interpreted as a bamboo panel, which is still used today for walls of traditional houses in Java and neighbouring islands as a material with good breathability, making a room quite comfortable in the hot, tropical climate (See the ikat weaver’s picture in Chapter 2). The meaning of the Chinese word, 正官, was not sure, but was interpreted as “just officials”. Since the early 13th century was the time when the Sunda Kingdom was weakened, it would not be unreasonable to assume that the country was not well administrated.

Samida Forest and Lake Talaga written on Batu Tulis

Back to the Batu Tulis stone monument. The description that Sri Baduga was crowned twice means that he was, firstly, enthroned in Kawali and secondly, ascended the throne in Pajajaran. His achievements, such that he constructed the roads to mountains, the mansion, Samida Forest and Talaga Rena Lake, were written also on Prasasti Kebantenan, a copper plate, discovered in Bukasi to the east of Jakarta.

Among them, Samida Forest is generally considered to have been the area of the present-day Bogor Botanical Garden, although one theory prefers to locate it at the area where the High-Altitude Botanical Garden exists, at Cibodas, beyond the Puncak Pass, seventy-five kilometres east-southeast from Bogor[10].

The lake of Talaga Warna Mahawijaya is no doubt Telaga Warna (Talaga=Sundanese; Telaga=Modern Indonesian), which exists in the Nature Reserve on the south col of Mt. Gede just before Puncak Pass, seventy kilometres to the south-southeast from Bogor.

I visited the lake once when I lived in Bogor accompanying a bird-watcher couple from Malaysia, but went there again recently after learning about its history. The lake, one of the sources of Ciliwung, which runs via Bogor to the Bay of Jakarta, was oval shaped, measuring 120 metres east–west and 60 metres north–south, and matched with nature as the heavy vegetation of the surrounding rainforest reflected on the water surface and chirps of birds echoed, causing me to forget the fact that it was an artificial dam constructed five hundred years ago by Sri Baduga Maharaja. According to a local gentleman, such fish as minnow, carp and ikan-mas, the largest fish being as big as one armful, lived in the water, of reportedly fifteen-metre depth at the innermost point, which was turbid with soil and plankton at the time of my visit, because it was the rainy season. To my question, he answered that the water was too cold for gurame, a famous fish in Sundanese cuisine. Although a tradition has it that a wish would be realised if one saw a pair of guardian fish, which lived there since ancient time, jump above the water surface, I had no chance.

Telaga Warna was a place where the legendary Bujangga Manik, a prince of Pakuan who became an ascetic monk, determined his mind to continue his practices during his second journey. In The story of Bujangga Manik [11], a long poem written in the 15th–16th centuries, he said, “Then I came to Mt. Ageung [Mt. Gede], that is the source of Ci-Haliwung, the sanctuary of Pakuan, the sacred lake Talaga Warna: Ah, what is my fate! I shall not be able to go straight on to visit my mother and father [in Pakuan], but visit the place of my teachers [in Java]!…”

It was in daytime with bright sunshine that I visited the lake twice, but a sacred atmosphere would have been there if it was dawn or dusk.

|

The lake of Telaga Warna. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012. |

The year 1455 Saka (1533 AD) inscribed on the Batu Tulis was during the reign of Surawisesa, the 2nd king of Pajajaran (1521–35 AD). Although he was a king praised in Carita Parahiyangan as a great ruler, warrior and hero who won fifteen battles in fourteen years, it was only several years after his succession that some coastal areas of his territory were encroached on by Moslems who developed from Central Java. In such a vulnerable situation, he is supposed to have erected this monument to commemorate his great father.

Sri Baduga Maharaja appears in traditional tales as Prabu Siliwangi, the nickname that is more familiar among Sundanese people. Due to the fact that the traditions were the kind that used to be orally narrated in poetic phrases, called Pantun Sunda, and dictated only in the modern age, different versions of short and long length are known today even for one title. Among them, Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi (The Story of King Siliwangi) was a tale in which his early life is told. Let us follow the story in a book, Khazanah Pantun Sunda (Treasure of Pantun Sunda) [12], which, as far as I have encountered, is the most comprehensive one.

“Pamanahrasa born of Prabu Anggalarang and Queen Umadewi of Pajajaran grew up to be an elegant and smart boy. When he was nine years of age, Parbamenak, his fifteen-year-old half-brother from one of the king's concubines, had conspired to murder him from envy of Pamanahrasa’s legal right of succession. He invited Pamanahrasa to Sipatahunan River, lying that he would help Pamanahrasa with testing the latter’s ability to be the future king. The first task was to cross the river that three white crocodiles inhabited, but Pamanahrasa was able to safely reach the opposite side, as the three savage animals somehow fought and killed each other. The second task was to climb up the Sanghiang Kekeumbingan by hauling a vine by arm power. When it was achieved, Parbamenak blamed Pamanahrasa that it was a serious sin to have set foot on top of the peak, which was a sacred worship place. Having been sentenced to be a slave, the whole body of Pamanahrasa was painted black with a compound of soot and sap and his name was changed to Siliwangi, to conceal his identity, before he was sold at a port to a nakoda [captain].

“In Sindangkasih [near the present-day Purwakarta], Dewi Ambetkasih, the daughter of Ki Gedhe Sindangkasih [the first younger brother of Prabu Wangi of Sumedanglarang], had a dream one night in which a black, ugly slave appeared, accompanied by a young man, and said to Ambetkasih that he would serve her as her younger brother, if she would buy him. While she hoped the dream would come true, one day her maid brought news that a nakoda from Palembang named Minadi was wishing to sell his slave to pay for repairing his damaged boat. Ambetkasih had lost no time to speak to her parents and took the black slaves in her custody in exchange for some teak wood and a small junk. After then, there was an incident that the garden of Ki Gedhe’s palace was often damaged. Siliwangi was suspected and created a problem for Ambetkasih.

“Meanwhile, three chamberlains of Siliwangi, i.e. Parwakalih, Gelap Nyawang and Kidang Pananjung, who had been in search of their master for five years, received an instruction from a hermit at Meru Kidul and came down towards Riwahan and reached Kampung Kategan to stay in disguise at Kuwu Kawanda’s house. The village became prosperous thanks to the farming skill of the guests. One day when Kuwu delivered fruits and vegetables to Ki Gedhe, his wife was much delighted with the quality of the crops and invited the three visitors to let them repair the damaged palace garden. They instantaneously recognised that the black slave they saw was their master, but kept it secret at that moment. Next day, when Ki Gedhe, his wife and the daughter went to see the restored garden, Siliwangi was also there. To Ambetkasih, who worried whether the garden would not be damaged again, the visitors told her to shower water on the slave’s body, as a boy with a skin disease was usually afraid of being made wet. No sooner water was poured than the ugly boy turned into a handsome young man to the surprise of the watchers. Ambetkasih gladly hugged Siliwangi and asked him to become her younger brother. At first, Siliwangi was hesitant, but eventually agreed, having been urged by Ki Gedhe. When the couple were dressed and decorated in royal costume, they looked like Kamajaya and Rati [the Hindu God and Goddess of Love].”

Above is the first half of the story. The last line apparently depicted the scene of their wedding, as it was mentioned in another Siliwangi tale, Ceritera Prabu Anggalarang ( The story of Prabu Anggalarang), that the couple did marry and became the king and queen of Sumedanglarang and then of Pakuan [13].

The second half of the story begins with the scene in Singapura [14] where Prabu Singapura was upset as her beautiful daughter, Ratuna Larangtapa, received marriage proposals from kings of eighteen countries and asked the advice of Ki Gedhe Sindangkasih, his second eldest brother. Then, Ambetkasih was despatched to Singapura on behalf of Ki Gedhe, accompanied by Siliwangi, to solve the problem. Leaving aside the details, which are rather complicated and verbose, Siliwangi, who had proposed to select the bridegroom by a cockfight and intended to be the referee, was inevitably entangled in the game and eventually obtained Princess Larangtapa by beating rivals. Many other princesses who gathered there and were admiring Siliwangi unanimously became his concubines.

Although Sri Baduga was no doubt the model of Siliwangi, the setting of the scene and the origins of characters are significantly modified in Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi. For instance, (1) in the tale, a kingdom called Pajajaran had already existed and Siliwangi (Panamahrasa) was born there as a prince, whereas the real Pajajaran Kingdom was founded in a later time by Sri Baduga himself; (2) Pajajaran Kingdom was implicitly written as if it had existed within the territory of Sumedanglarang, with no indication of its capital’s location; (3) the name of the father of Siliwangi in the tale, Prabu Anggalarang, was the alternative name of the 5th king of Kawali, Wastu Kencana, in the chronicle; (4) Prabu Wangi, the name of the king of Sumedanglarang is generally the honorific name of Maharaja Linggabuwana, the 3rd king of Kawali, who was killed in Majapahit [15], etc.

In Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi, it is also noteworthy that Princess Subanglarang, the daughter of Patih Mangkbumi, or the youngest brother of Prabu Wangi, who became the second queen of Sri Baduga appeared just as a minor character, and that Princess Kentring Manik Mayang, the daughter of Prabu Susuktunggal of Sunda Kingdom, whose future marriage with Siliwangi as the third queen was to realise the unification of Kawali and Sunda Kingdoms to found Pajajaran, was not included at all.

This story was allegedly written in Sumedang around the turn of the century from the 17th to the 18th when the Pajajaran Kingdom with its capital at Pakuan had already ceased to exist, and Banten in the coastal area on the west part of the Java Sea, the Kingdom of Mataram arisen in Central Java and VOC (the United Dutch East Indies Company) at Batavia were struggling for supremacy. Although Sumedanglarang had managed to maintain its existence, its status as a country was in jeopardy. It was commented by the author of Khazanah pantun Sunda that, in such circumstances, the court of Sumedanglarang would have preferred to imagine Sumedang as the centre of the glorious Pajajaran Kingdom.

The moving of Ambetkasih to Pakuan from the old capital together with her fellow consorts of Siliwangi is written in Carita Ratu Pakuan [16], in which the procession of palanquins, decorated with gold and jewellery and topped with an ivory ball, started at the shining palace of the east, being led and followed by bands, chorusing, “Let's go to Pakuan!”, as if the procession were waving in the air like a dragon.

The Story of Mundinglaya Di Kusumah

An episode of Siliwangi after his coronation was told in Mundinglaya Di Kusumah. One of many versions is narrated [17] as follows:

“The story begins with the scene in which one of the two queens of Prabu Siliwangi of Pajajaran, Padmawati, wished to eat a sour fruit, honje, when she was expecting a baby. Since no ripened honje was found in the country, a confidant of the king went around forests and reached Muara Beres where the confidant of the latter country was picking up the same fruit. The request of the former to hand them over was rejected, because the queen of Muara Beres, Gambir Wangi, was also pregnant. After quarrelling for a while, they realised that the two kingdoms had descended from a common origin and agreed to equally share the eight pieces of the fruits in such a condition that if the two expected babies were of different sex, they should be engaged. After the full term, Padmawati of Pajajaran gave birth to a boy, named Mundinglaya Di Kusumah, and Gambir Wangi of Muara Beres, a girl, named Dewi Asri.

“It was when Mundinglaya Di Kusumah grew up to be a handsome and smart young man that he was insistently slandered, as if he had misbehaved with a young court lady, by another queen of Siliwangi, Nyi Raden Mantri, whose son, Guru Gantangan, was much older and was already the governor of Kutabarang district. Without much investigation, Mundinglaya was jailed. This caused some turmoil in the kingdom.

“One night, Padmawati saw in a dream a beautiful kite with twenty-five golden tails that was brought almost within her reach by some invisible being. When the king summoned scholars and elders and told of his wife’s dream, a famous astrologer explained that the kite was called Salaka Domas which symbolised welfare and happiness, and that a person who obtained it would ensure the prosperity of the kingdom with eternal life. He added that the kite existing in the heaven was guarded by seven heavenly beings called Guriang Tujuh. The king called his one hundred and fifty sons, but nobody was willing to go on the dangerous journey to get the kite. Then, Padmawati remembered her son in the gaol. When her thought was delivered to Mundinglaya by two chamberlains, Gelap Nyawang and Kidang Pananjung, who both had long served him, he who had enhanced his mental culture even while in prison said that he was very eager to undertake the mission. When he was released for his expedition, Prabu Siliwangi gave him a keris called Tulang Tonggong, a treasure sword of Pajajaran.

“Mundinglaya departed for the heaven accompanied by the two chamberlains. First, they went by boat to the north to Pulau Puteri, a small island in Java Sea, to worm the secret route to the heaven and to obtain magical power from Jonggrang Kalapetong, a giant who lived there, and finally attained the aim by beating the giant. Mundinglaya Di Kusumah flew to the sky and, as expected, encountered Guriang Tujuh. When he was strangled to death and became free from both mental and physical restraints, Goddess Wiru Mananggay, the late grandmother of Mundinglaya, descended and breathed life into the body to revive him as a perfect man qualified to hold Salaka Domas. He returned to the earth, accompanied by Guriang Tujuh who had become his retainers.

“In Muara Beres, his fiancée, Dewi Asri, was in danger, being proposed marriage by Sunten Jaya, the step-son of Guru Gantangan, but Mundinglaya was able to rescue her with the help of Jonggrang Kalapetong whom he had subdued before. In Pajajaran, Mundinglaya Di Kusumah produced Salaka Domas to Prabu Siliwangi and married Dewi Asri. Thus, peace was restored in Pajajaran.”

The details of the story are significantly different between versions. As to the reason of Mundinglaya’s imprisonment, it is told, for instance, in one version, that “While Guru Gantangan and his wife, Nyai Mas Ratna Inten, were fostering Mundinglaya by request, the wife was so much absorbed in Mundinglaya Di Kusumah and forgot about her husband that the husband became angry”[18], and in another version that “Sunten Jaya, the step-son of Guru Gantangan and Nyai Mas Ratna, became envious of Mundinglaya Di Kusumah as his step-parents doted on the latter”[19], and so on. Mundinglaya Di Kusumah is considered to have been modelled after Surawisesa, the 2nd king of Pajajaran [20]. The fact that such an episode was written in Pantun Sunda suggests that some dispute about the succession of throne existed in the court even after the inauguration of Siliwangi, or Sri Baduga Maharaja.

Pajajaran Kingdom recorded in European books

The situation of the Pajajaran Kingdom was also documented to some extent by Europeans. The era of Sri Baduga Maharaja’s reign was already in the Age of Exploration (for Europeans), which had started in Asia by the arrival of Vasco da Gama at India in 1498, and it was the so-called Portuguese Era. Tome Pires, an adventurous young man who had abandoned his position in Lisbon as a pharmacist for Prince Alfonso and who was later to become the first ambassador to Ming of China, came to India in 1511, the year of the Portuguese acquisition of Malacca. The next year, he visited Java and other islands in the East Indies on board a vessel despatched by the Commander of Malacca, Rui de Brito, and authored a book. [21]

Whether Tome Pires himself had set his foot on Java was not certain to us; he wrote about the capital of Sunda as, “The city where the king stays most of the year is the great city of Dayo [dayeuh, town or city in Sundanese]. The city has well-built houses made of palm leaves and wood. They say that the king’s palace has three hundred and thirty wooden pillars which are as thick as a wine cask and five fathoms high [1 fathom =1.8288 m], and on top of the pillars are beautiful wooden frameworks. The city is located at the distance of two-day journey from the chief port which is called Calapa. The king is a great sportsman and hunter. In his country are numerous deer, pigs and bullocks. They do this [hunting] any time. The king has two chief wives[22] and one thousand concubines. The people of Sunda are said to be truthful… Calapa is a magnificent port. It is the most important and best of all.” Calapa, which meant Sunda Kelapa (to be renamed in later years as Jayakarta, Batavia and Jakarta), was directly linked to the capital, Pakuan, by Ciliwung River.

As other seaports, Pires listed up Bantam (the present Banten Lama), Pontang (at the estuary of Ciujung), Tangeran (now inland), Sumano (the present-day Indramayu at the estuary of Cimanuk?) and some others. As major exporting goods, he recorded 1,000 barrels of good-quality pepper, 1,000 boat-fuls of tamarind, 10 junk-fuls of rice, enormous amounts of vegetables, fruits and meat, as well as male and female slaves from their own country and from the Maldive Islands, and, as imported goods, high-quality fabrics and perfumes from India, indicating the prosperous situation of the country. Pires also mentioned that the Pajajaran Kingdom embraced Hinduism and the custom of suttee, the suicide of a wife at the death of her husband, was commonly practised.

A contemporary historian and official, Joan de Barros [23], who also left a voluminous work, estimated that the total population of Sunda was about 100,000, that of each town, some ten thousands.

After the Prophet Muhammad initiated Islam in 622 AD, the Moslems, who first advanced westward to North Africa and Balkan and finally occupied Granada in the Iberian Peninsula in 711 AD, expanded also eastward and founded their own country in India before the end of the 10th century (Ghaznavid dynasty 955–1187). Although the Moslems who came to the East Indies were not soldiers but seafarer merchants, they settled at Malacca and other port towns and spread their religion. Marco Polo who dropped in at Sumatra in the late 13th century on his way back from China (1292?) wrote in his travelogue[24] that the most part of Java Minor (i.e. Sumatra Island) was already Islamised, while, according to the hearsay of seafarers, the people of Java Major (i.e. Java Island) were idolaters. In fact, it was just around the time when two strong Hindu kingdoms, Kawali in the west and Majapahit in the east, founded in 1333 and 1293, respectively, existed in Java. In the 15th century, however, Islam began to prevail in the coastal area of Central and East Java and the first Islamic kingdom, founded in Demak in 1475, conquered the capital of Majapahit three years later.

Joan de Barros wrote in 1514, “The Islamic merchants who came from Malacca to settle in Java turned to be conquerors and occupied seaport towns along the [north] coast of the island, so that the heathens [Hindu] became unable to sail. By the attack of Islam, the latter retreated to the inland at the foot of the mountain range which lay east to west in the middle of the island.”[25]

The influence of Islam extended to West Java already during the reign of Sri Baduga Maharaja. The description in Carita Parahiyangan that “as long as the teaching of our ancestor is upheld, no enemies, neither soldiers nor mental illness, will come. Happy prosperity prevails in the north, the west and the east. Those who do not feel the prosperity of household are greedy people who learn [foreign] religion” suggests that many populations in the kingdom’s territory were already inclined to Islam. The second queen of Sri Baduga Maharaja, Nyai Subanglarang was, in fact, a Moslem who attended an Islamic school in Karawan [26]. Although one of her sons, Walangsungsang, who became the sultan of Cirebon still had respected his father, his son, Syarif Hidayat, declared independence from Pajajaran by allying with Demak in 1482. Angered by this, Sri Baduga attacked Cirebon but was stopped by the Cirebon–Demak allied army. Although Pajajaran had one thousand men and forty war-elephants, they had only six 150-ton class junks in the sea, which were not compatible with the strong navy despatched from Demak.[27]

With respect to the relation between the king of Pajajaran and Moslems, there is a tradition which tells [28]:

“The kingdom of Pajajaran was ruled by its glorious king, Prabu Siliwangi. Prabu Siliwangi had a son named Kian Santang, a man with great mystical powers. One day, Kian Santang walked on the water to Mecca and was converted to Islam. He returned to Java, assuming the name of Wali Sunan Rahmat. There he attempted to convert Prabu Siliwangi to Islam, but the latter and some of his courtiers rejected the new religion. A confrontation ensued and the king and his court fled into the Sancang forest on the south coast of Java Island, having been pursued by Kian Santang. To avoid a battle with his son, Prabu Siliwangi disappeared and turned himself into a white tiger while all his followers became Sancang tigers. They spread all over the forest and are today considered as an omen of good luck by local fishermen. In his tigrine form Prabu Siliwangi, who is said to still inhabit the area of his old court at Pakuan near Bogor, continues to watch over his descendants and the Sundanese generally.” [29]

In this connection, the famous Siliwangi Division of the Indonesian Army has been named after Prabu Siliwangi and in front of their garrison in Bandung is placed a statue of a white tiger as their symbol. The emblem of Persib Bandung (lit. Bandung United), a strong football team in Indonesia, has a head of a tiger and their home ground is called Lapangan Siliwangi (Siliwangi Field).

In his travelogue[30] of 1512, mentioned above, Tome Pires wrote that Cirebon had been a town of the heathens (Hindu) until forty years ago and he put it in the paragraph of Java, not in that of Sunda. As he also wrote, in order to prevent the further expansion of Moslems, Sri Baduga Maharaja despatched his son, Surawisesa, twice in 1512 and 1521, to Malacca to link up with the Portuguese and signed a friendship treaty on 21st August 1522 giving permission for the Portuguese to construct forts at Bantam (the present-day Banten Lama) and Sunda Kelapa. The document of the treaty remains to date in Portugal, while in Java the stone monument (called Padrao in Portuguese), which had been erected to commemorate the treaty, was accidentally found in Jakarta in 1918 and stored in the National Museum.

|

The monument of Pajajaran–Portuguese Treaty (genuine). Indonesia National Museum. Photographed with permission by M. Iguchi, February 2012 |

Since the hegemony of the Portuguese in the west part of the Java Sea was harmful for the trading of the Moslems in central Java, they gave an order to the commander of Cirebon, Fatahillah (alias Faletehan) to attack those ports, prior to the completion of Portuguese forts, and captured Sunda Kelapa in 1527, after suppressing Bantam in the previous year. The Portuguese visited there three days later on three ships without knowing that event had occurred. They were expelled and fled losing one of the ships. In 1529, they attempted to regain Sunda Kelapa by sending a fleet of eight military ships in vain and could not make contact with Pajajaran after then[31]. Although a peace agreement was signed between Pajajaran and Cirebon in 1531, the landlocked Pajajaran was weakened and their capital, Pakuan, finally fell in 1579.

A half-century later, Jan Huygen van Linschoten [32], a Dutchman who sailed to Asia on a Portuguese ship and whose book became useful for the Dutch expedition to Asia, wrote that the most important port of Sunda was “Sunda Kelapa” and that there were abundant high-quality peppers, frankincense, benzoin and nutmeg in the land of Sunda, despite the port town had been renamed by Fatahillah on 22nd June 1527 as “Jayakarta” (lit. Big victory), which corrupted as Jaccatra in Europe and Jagatara in Japan. In the 1600s, Jayakarta became the field of a power struggle between the Dutch and the English, but the former established the supremacy in 1619 and renamed it Batavia, after the Latin word, Bataaf, for Hollanders. The presence of the Dutch was solidified when they rejected the attacks of Sultan Agung of Mataram in 1628 and 1629.

Exploration of the old capital of Pajajaran by Dutch people

One half-century later in 1687, an expedition team of VOC headed by Pieter Scipio van Ostende went south from Batavia and passed a place that was supposed to have been Pakuan, the old capital of Pajajaran, in the ravine to the west of Mt. Salak and to the east of Mt. Gede, before they reached the bay of Muara Ratu on the southern coast of Java Island for the first time as foreigners. Van Ostende reported that “the road from Parung Angsana to Cipaku[33] was wide and macadamised, and durian trees were lined on the both sides. At the end of the road was a moat, and beyond the moat was a gate. In the front was a ruined stone masonry, but expedition members were not allowed to go inside the palace, because they were non-Moslems. The area was guarded by tigers. Inhabitants were sparse around there. They still respected the former king, Prabu Siliwangi, etc.” This record indicates that the former capital with an estimated fifty-thousand population was in the state of a ghost town, one century after the fall of the kingdom. It is interesting if tigers were tamed as watchdogs, but it is written in Prof. Danasasmita's book that the tigers were probably wild ones that dwelled there[34]. Otherwise, were they the transformations of Siliwangi and his followers as told in the legend?

Van Ostende also wrote that he was told that the custodian was a noble. He was supposedly not the descendant of Pajajaran but a dignitary from Banten whoconquered there.

Three years later, VOC sent another expedition led by Captain Adolf Winker. The most important fact written in their survey report was that they entered within the wall of the castle and saw a stone monument, on which eight and a half line letters were inscribed. The stone that Winker saw must be nothing but the existing Batu Tulis, the last half-line being four words to denote the date. He also recorded that he saw three stone figures in the neighbourhood of the monument.

In 1703 and 1704, a high official of VOC, Abraham van Riebeeck (a son of Joan, the founder of Cape Town), himself went to survey Pakuan. In 1709 again, after he became the governor-general, he dropped in at the same place on his journey to the east to Cianjur across the Gede mountain mass. He was alleged to have been so taken by Pakuan that in 1704 he built a cottage that he called “Batu tulis”, near the stone monument, which was to be adopted as the names of the stone monument and the area.

|

Bogor map (Prepared on Kota Bogor, C. V. Pradika, Jakarta 1995). The outline of Pakuan city wall, from S. Ekadjati, Kebudayaan Sunda Zaman Pajajaran, Jilid 2, Pustaka Jaya, 2005/C. M. Pleyte 1911. According to T. S. Raffles, The History of Java, London 1817 (Vol. I, Reprint, Oxford University Press, Singapore 1988), Salaka Domas was a large hall with 800 pillars. |

After then, the area of Bogor had been almost forgotten until 1744 when Baron van Imhoff, the then governor-general of VOC, acquired his private estate and built a mansion [35], naming the place as Buitenzorg (lit. care-free village), away from the miasmatic Batavia.

Today, almost no trace of the former glory of the Pajajaran Kingdom is seen around the city, but one interesting relic besides the Batu Tulis stone monument is Situs Purwakalih (or Purwakalih Site), a site of about 4 × 3 metres located 300 metres south of the Batu Tulis monument, adjacent to which is believed to have existed the gate of the former castle. In this site, the three stone figures recorded by Winker remain. According to legends, they represented the figures of three chamberlains, Purwa Kalih (or Galih), Gelap Nyawang and Kidang Pananjung, who served the kings of Pajajaran, as the first name represents the site. The statues were of a kind that long and narrow metamorphic rocks were crudely sculpted into human shapes, and more or less resemble old dousoshin (travellers’ guardian deity) found in countryside Japan. According to my friend, Mrs. E., who went along with me there, they would have originally been some stoneworks of prehistoric time. Among the three figures, Parwa Kalih’s figure was seriously damaged and lacked its head, presumably having been broken by the hand of Moslem conquerors, and the figure itself of the third one was very rough and obscure.

|

Situs Purwakalih, Bogor. Photographed with permission of the caretaker by M. Iguchi, February 2011. |

As written above, all three characters appeared inCariosan Prabu Siliwangi, and the second and the third ones inMundinglaya Di Kusumah [36]. Although they who served the kings of many generations were old, they are believed among Sundanese people to have had eternal lives. [37]

While these remains had been surveyed in 1911 by Cornelis Marinus Pleyte, a pioneer Javanese archaeologist, they were hidden in the soil until 1991 when they were accidentally rediscovered during the road-widening work and cleaned.

An account of the relics of the palace was found in Serat Centhini (The Centhini Story) [38], a travel record of the early 17th century, which I obtained recently. It was about a half-century after the fall of the Pajajaran Kingdom’s capital, Pakuan, that Raden Jayengresmi and his two followers from Giri, East Java, arrived at Bogor. Welcomed by the village chief, Ki Wargapati, they then visited the ruin of the palace.

“There is a large pool full of fresh water. According to a legend, if the husband and the wife of a childless couple take bath in the pond everyday, they will be blessed with a baby within a matter of three days or seven days. Close to the pond are several pieces of stones covered by flowers. It is said that one’s wish will come true if he/she prays to the stone. Since this tradition is famous, many people came from far away places. This stone is called Kyai Selagilang.”

Although the name, Kyai Selagilang is not found other than inSerat Centhini, one of the stones must be the Batu Tulis, which remains to date [39]. Raden Jayengresmi prayed to this stone and, with the help of some men arranged by Ki Wargapati, successfully built a hermitage on the plateau on the western slope of Mt. Salak where fresh water streamed and beautiful flowers blossomed. Raden Jayengresmi and his followers stayed there for a while to practise asceticism.

Why are the remains and relics of the Pajajaran era so few? While documents are assumed to have been neglected, if not intentionally destroyed by Moslems, the question remains why stone masonries, even their foundations, are invisible. Although it is a mere layman’s idea, they might have been buried under the earth by volcanic ash and landslides, as Mt. Salak and Mt. Gede to the west and east were always active [40]. Natural disasters would have urged inhabitants of Pakuan to evacuate from the area, in the land of Sunda, where the saying that “a people can subsist without a king… but it is even impossible to conceive a thought of a king without a people” [41] was also true.

Buitenzorg was developed as a modern city after 1870 when the private mansion of van Imhoff was made the official residence of the governor-general of the Dutch East Indies. Having been renamed as Bogor after the independence of Indonesia, it has grown to the present big city with a one-million population including the suburbs. The area of Pakuan Castle is densely housed to the extent that archaeological excavation is hardly possible.

|

Two sceneries around Bogor in the late 19th century painted by Johannes Rach. By permission of Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, reproduced from the museum’s websites. Top: A pasture located between Mt. Salak (right) and Mt. Pangrango (left) (Identification Code NG-400-N) Bottom: Batu Tulis (Identification Code NG-400-I). |

Royal treasures of Pajajaran remaining in Sumedanglarang

When Pakuan fell to the hand of Moslems in 1579, nobles of Pajajaran fled to a vassal country in Sumedang, some 150 kilometres east by southeast, with the crown and other heirlooms of Pajajaran. Prabu Geusan Ulun, the king of Sumedanglarang, who warmly welcomed them, declared that he would be the successor of Pajajaran, but it was only until the end of his reign (1601) that they were able to resist the Moslems and, in his son’s time, they were put under the rule of Sultan Agung of the Mataram of Central Java.

In Prabu Geusan Ulun Museum, named after the king, are held several dozen pieces of treasures from Pajajaran, which include a golden crown, accessories, small furniture, decorated hats, etc., along with the treasure keris and other belongings of Prabu Geusan himself, all in immaculate condition. For many generations, the people of Sumedang must have made efforts to keep those Sundanese heritages, lest they should be passed to the hands of the Islamic conquerors and the Javanese. I was quite impressed that the high-level craftsmanship that produced those elegant and delicate fretworks and reliefs existed there in the period contemporary to the Adzuchi-Momoyama Era in Japan, but the tradition was not succeeded after the Islamisation. The building of this museum, which used to be the house of the Bupati (Regional Governor [42]) built during the Dutch time, was not gorgeous but neat and tidy, retaining the good atmosphere of old days.

| A part of the crown and other royal accessories of the Pajajaran Kingdom carried to and hidden in Sumedang. Collections of Museum Prabu Geusan Ulun. Photographed with permission by M. Iguchi, January 2009. |

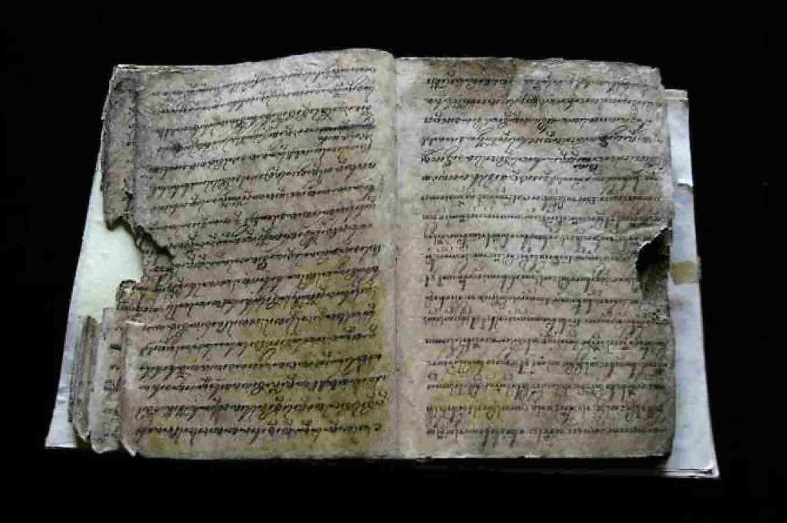

In addition to those treasures mentioned above, there was some furniture, old documents, sets of gamelan instruments, a big dragon-human-pulled carriage, etc. Among them, the most interesting to myself were three old books, one of them being entitled Kitab Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi (The Story Book of Prabu Siliwangi), labelled as a belonging of Prince Panenbahan (1656–1706). It must be one of the earliest copies of the book, although whether it was the very original copy was not sure. The material of the three books resembling traditional Japanese paper was called “daluang” prepared by hammering the white inner bark of paper mulberry tree ( Broussonetia papyrifera). The letters were written in black ink. I knew that daluang was used for wayang beber [43] but saw a book of the same material for the first time[44]. The second book was Kitab Waruga Jagat (1675) on the regional history, which also belonged to Prince Panenbahan, and the third one was Al Qur’an with some colour ornaments, which was owned by Prince Soeria Koesoemah Adinata (1836–82). I was touched by the fact that the technique to make the traditional daluang paper was still preserved in the middle of the 19th century when the modern paper-making technology must have been already common.

|

A book of Cariosan Prabu Siliwangi, written on daluang, or bark paper (1675). A belonging of Pangeran Panembahan (1656–1706). A collection of Museum Prabu Geusan Ulun. Reproduced from the brochure, Profil Museum Prabu Geusan Ulun. |

Graveyard in the Bogor Botanical Garden

In the Bogor Botanical Garden, under the shed of trees on the bank of Ciliwung River, one finds a small graveyard of some ten metres square, surrounded by an iron fence, in which three Islamic-style tombs are laid. They were said to be the graves of the Pajajaran time. According to a booklet[45] that someone once showed to me some ten years ago, the front one inside of the gate was the tomb of Ratu (Queen) Galuh Mangka Alam Prabu Siliwangi and the other two were those of Pangrima (War Commander) Mbah Djepara and Patih (Minister) Eyang Baul, who both served the king of Pajajaran. No other literature that mentioned these three names was found at that time.

|

Graveyard in the Bogor Botanical Garden. Photographed by M. Iguchi October 2007. A queen and two retainers of the Pajajaran Kingdom are buried according to tradition. |

I had then imagined. Although Siliwangi was originally the nickname given to Sri Baduga Maharaja, it was also applied to other kings of the same royal line. From the fact that the tomb of the king did not exist, the husband of Galuh Mangku Alam could have been a different person, e.g. Suryakencana, the last king of Pajajaran, whose name was to remain in the main shopping street in the present-day Bogor and who abandoned Pakuan and went into exile in Kaduhejo on the foot of Mt. Palasari in the western part of the kingdom’s realm, before the Moslems came to capture the capital in 1579. If so, a certain Moslem wife of his would have failed to persuade her husband to convert his religion from Hindu to Islam and remained separately in Pakuan together with the minister and the war commander and buried in this place, etc.

Several years later, a similar story with regard to this graveyard appeared in a novel as the words of a character, “To tell the truth, four people were buried there. One of them was Prabu Siliwangi [1474–1531], but his tomb is invisible to our eyes. The tomb in front of us belongs to his second consort, Ratu Galuh Mangku Alam. The tomb on the upper step is for Mbah Jepara and the one on the right-hand side is for Eyang Baul, the king’s war commander. These graves were created about 600 years ago in the 1450s.[46]” If this Prabu Siliwangi was Sri Baduga Maharaja, Ratu Galuh Mangka Alam could be identified as the second queen, Nyai Subanglarang, who was an Islam believer, and the style of the tomb matched her. Nevertheless, this was not certain, as the name Ratu Galuh Mangku Alam has not been found in historical documents, as far as I have searched.

In an internet article[47], it was written that the three tombs used to be humble stone mounts with no epitaphs and one of them was even suspicious as to whether what was buried in it was a human or an animal, and that they were reinterred in the 1980s by Mr. Aang Kunaefi, the then Governor of West Java, who felt pity for the queen and the retainers. A question remains whether those three persons were really Moslems. According to my friend in Bogor, the names and titles had no hint of Islam, so the possibility that their religion was traditional Hinduism was undeniable. Then, it was probable that the Islamic grave-style might have been adopted for the sake of convenience when the graveyard was reformed by Mr. Kunaefi.

The graveyard is always cared for by a few people who mow weeds and offer flowers. Whatever their religion, people of Sunda still have affection for the kingdom of Pajajaran. Whenever I visit there, I think of the ancient time and offer some small notes.

The tombs are considered to have existed since before van Imhoff acquired the land for his manor in 1744, a part of which was to be given for Reinwaldt to open the Botanical Garden in 1817. In fact, the graveyard does not seem to be under the management of the Botanical Garden, as no relevant description is written in its brochures and guidebooks. Whether the theory that the palace of Pajajaran had existed on the ground on which the Buitenzorg Palace (the present Bogor Palace) was built [48] is right or not, the possibility that some construction would have existed could not be denied, as the area was allegedly the holy Samida Forest, and was the best place on Bogor Hill. While writing this, I remembered the history of Colchester, England, where I once lived for a couple of years. The Norman Castle, which still remains in the town centre on the hill of Colchester, was constructed in the 11th century on the original place of the ancient Claudius Temple built by the Romans in the 1st century, as proved by archaeological excavation. No plan to dig and survey the underground of Bogor Palace is heard.

Let us pick up some topics with regard to the period after the Sunda Kingdom inherited Tarumanagara in 669 until the Pajajaran Kingdom was established at Pakuan in 1482.

Relatively recently, I was informed that the remains of the Galuh Kingdom existed to the east of Ciamis and I visited there. In front of the entrance of the site, there was a board saying, “Welcome to Ciung Wanara Karang Kamulyan”, and another board on which nine kings who resided there were listed along with their periods of reign [49].

| A board at the site of Karang Kamulyan, Galuh, listing the names of kings and the periods of their reigns. Photographed by M. Iguchi, January 2009. |

Inside the gate was a jungle of various rank trees and bamboo, and about fifty metres ahead of the path, which was like a tree tunnel, was a rectangular open space that was a little larger than a tennis court, surrounded by a low-height stone embankment. In the innermost part of the space was a white square stone about one metre wide and fifty centimetres high, called Pangcalikan, which, according to the guide, used to be the place where the kings had audiences, but looked a little shabby for a royal seat even though it was equipment of the 7th–8th centuries. Further ahead were places for prayer and maternity. There was also anarea with a long stone, standing upright, which was presumably the tomb of a noble. One interesting place was an area of about ten metres diameter in the bottom of a depression, which was said to be a pit for cockfighting. I learnt that cockfights had been common even in ancient time. Although it was a favourite game of Javanese people, cockfighting was prohibited in modern times because of its high speculativity. Several hundred metres ahead in the southeast corner of the site was the confluence of the Citanduy and Cimuntur rivers, which came from the west and north, respectively. On the voluminous, muddy water of ochre colour, a few pleasure boats were seen. I realised that, with the north, east and south sides of the rectangular Karang Kamulyan site of about twenty-five hectares being edged by rivers, the site was chosen for the royal capital not only from the viewpoint of transportation but also from defence.

| Ceremonial place with the king’s seat in Karang Kamulyan. |

|

The confluence of Citanduy River (right) and Cimundul River (left). Photographed by M. Iguchi, January 2009. |

“Ciung Wanara”, a nickname of the 10th king of the Kendan/Galuh Kingdom (the 8th of Galuh Kamulyan), was probably prefixed to the name of the remains because it was popular among Sundanese people as a title of Pantun Sunda. The story goes as follows [50]:

“It was when King Sang Permana Kusumah of Galuh was aged and intended to retire from the world that he noticed the desire of Minister Aria Kebonan to be a king. The king called the minister and told him to rule the country but not to harass his two empresses, Pohaci Naganingrum and Dewi Pangrenyep. After his departure to Mt. Padang [51], Aria Kebonan, who somehow resembled the king of ten years younger age, behaved rapacious, declaring the title of Raden Galuh Barma Wijaya.

“In the hermitage on Mt. Padang, an ascetic, Ajar Sukaresi, saw some light from the sky entered the palace and the bodies of the two empresses. Meanwhile, Naganingrum dreamt the stars fell on the moon and Dewi Pangrenyep, a sharp sunlight penetrated the seabed. Barma Wijaya did not believe the dreams and summoned an ascetic from Mt. Padang, but he did not appear soon, just sending some jasmine flowers and turmeric. Barma Wijaya who felt insulted, ordered the empresses to pretend to be pregnant by putting a pot on each stomach. The ascetic, Ajar Sukaresi, who was the former king, Sang Permana Kusumah [52], arrived there and asserted that they were six months pregnant and that both babies would be male. Barma Wijaya was angry and stabbed the ascetic with a keris. The ascetic did not die, as the keris broke into three pieces, but he understood the aim and transformed himself into a snake called Naga Wiru.

“Dewi Pangrenyep first gave birth to Raden Aria Banga. The baby in the womb of Naganingrum voiced and warned the greedy king that the country will soon be destroyed. When Naganingrum delivered the baby, Dewi Pangrenyep who was envious of her fellow concubine swapped the baby with a puppy. The baby was put in a casket with a piece of egg and washed away into Citanduy River, whilst the mother who was sentenced to death was saved by a loyal chamberlain and put in a forest. The casket was found by Aki and Nini Balangantrang in a fish trap installed in the river and the baby was fostered by the couple. After the baby grew to a boy, the boy flew to the air and saw that the heaven and the earth were still separate, a sign that he was entitled to get some inheritance. The child created a village for Aki and Nini.

“One day Aki and the boy went for hunting to the forest with blowguns. When the boy saw a bird and an animal, and asked their names, Aki taught that they are called ‘ciung’ and ‘wanara’, respectively. Then the boy said he must be called Ciung Wanara. From Aki, Ciung Wanara heard of his identity that he was the son of the former king of Galuh and his empress, Naganingrum.

“The egg which had been found along with the baby in the trapped casket turned into a cock, named Si Kakat Beds, when incubated by Naga Wiru. When a cockfight contest was announced from the court, Ciung Wanara wished to challenge Barma Wijaya. The latter who was confident in winning the game with his magical cock, Si Kakat, accepted Ciung Wanara’s challenge, agreeing that the west part of the territory would be submitted to Ciung Wanara, if he was to lose. Si Kakat Beds won the game to obtain the west part of the kingdom for Ciung Wanara. Ciung Wanara was not quite satisfied, as he must be the crown prince of the kingdom. One day he made a beautiful iron cage. When Barma Wijaya and Dewi Pangrenyep came to inspect it and just entered the door to see the inside, Ciung Wanara lost no time to close it. Aria Banga who saw this incident asked Ciung Wanara to free them, but this was not agreed. Then a severe fight began between them and, finally, Aria Banga was hurled by Ciung Wanara to the east of Cipamali River. Thereafter, Ciung Wanara and Aria Banga ruled the western and the eastern parts of Java Island bordered by the river.”

That an iron cage was used in the 8th century might sound unrealistic, but it could be possible to make one by the forge-welding method by employing the tempering technique, which existed since ancient time to make keris and other weapons.

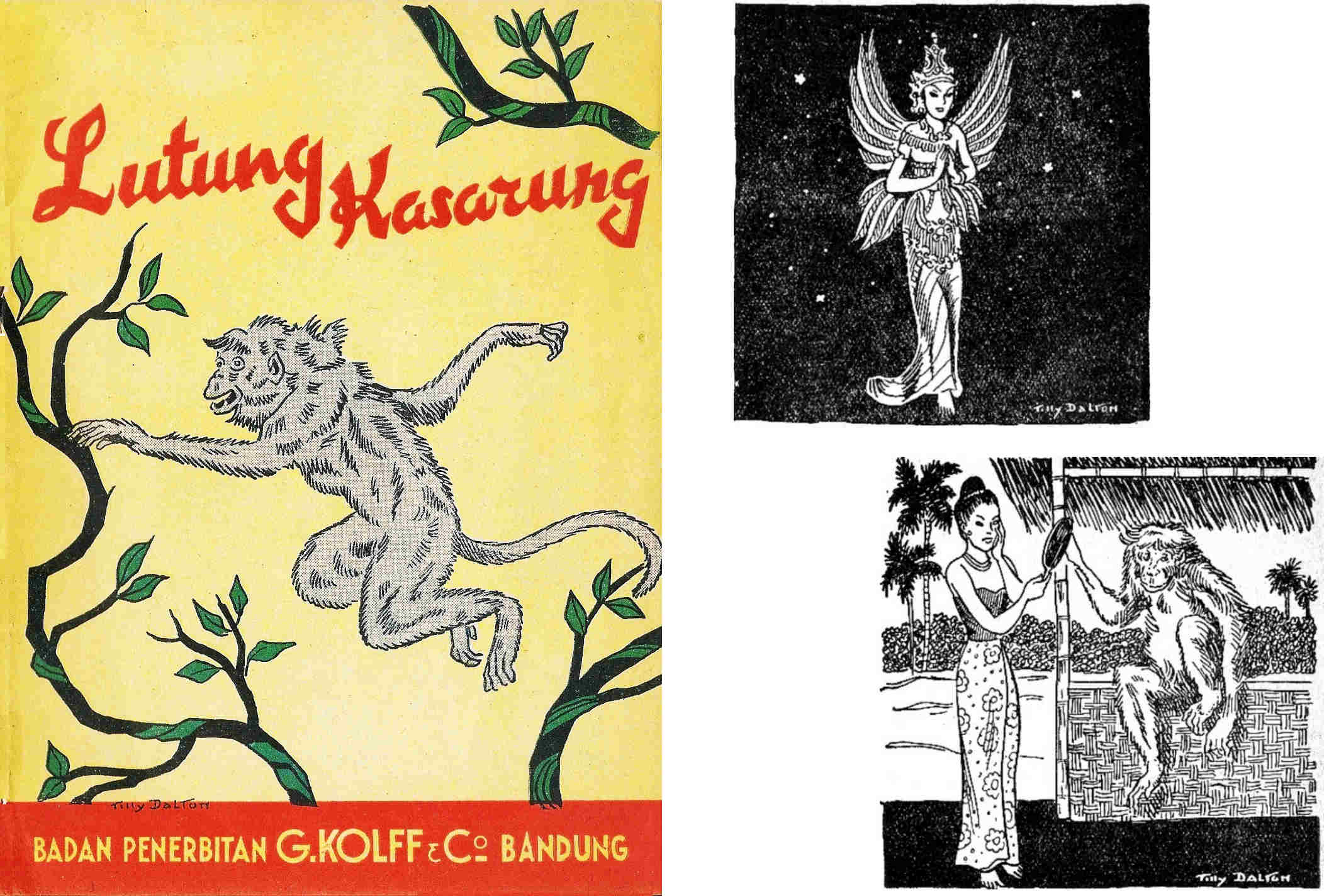

Lutung Kasarung, another title of contemporary Pantun Sunda that must be related to Manisuri (or Dharmasakti), the son-in-law of Ciung Wanara, is also famous. One version, which was written in a picture book like a fairytale, is as follows [53]:

“Guru Minda, the son of Dewi Sunan Ambu in Kahyangan [Heaven] was transformed into Lutung Kasarung [Black Monkey] and pushed down to the earth, because he wished to love her mother. He was taken to the palace by a hunter, where Purba Rarang, the elder daughter of Prabu Tana Agung, was monopolising the power by poisoning her younger sister, Purba Sari, to suffer from a skin disease and isolating her in the forest. She did it as she was jealous when the king was about to hand over the throne to the younger sister in accordance with the custom. Lutung Kasarung who was expelled from the palace, disliked by Pruba Rarang, met grief‐stricken Purba Sari in the forest, where Sunan Ambu occasionally appeared and gave her hand. Purba Sari was actually born to Prabu Tana Agung and his queen when they wished to have a beautiful daughter like Dewi Sunan Ambu who had appeared to their bedside. When Purba Sari bathed in a pond created by the tears of Sunan Ambu, her skin was healed and she revived into a beautiful princess.

“Although Purba Rarang gave various difficult problems to the younger sister, Lutung Kasarung solved them one by one. Purba Sari went to the palace. As soon as she heard the voice of heaven and declared that she was the legal successor, Lutung Kasarung took off his coat and turned into a handsome young man. They ruled the country wisely and the kingdom of Galuh prospered.”

| Cover and some illustrations of: Till Dalton (Illust.), Lutung Kasarung, G. Kolff & Co., Bandung (ca. 1950). |

The episode that the pond water was effective for the skin disease of Purba Sari could mean that it was hot-spring water from volcanoes existing in the surrounding areas.

Among various long and short versions of Pantun Sunda [54], a story recorded in Stamford Raffles’s The History of Java [55] , probably a dictation of a narration, is very specific in that the above two stories were connected. In short, it is written that Lutung Kasarung was the name given by his father, Ciung Wanara, together with a black-monkey coat, and that a son born between Lutung Kasarung and Purba Sari was Silawangi (Siliwangi) who became the king of Pajajaran, which prospered under his reign. Although there was actually a time difference of more than 600 years from the end of Galuh in the middle 9th century to the foundation of Pajajaran in the late 15th century, presumably the narrator would have linked the two historical heroes by his own idea in this fictional tale. One point that is common in both Lutung Kasarung and Siliwangi stories can be that both of them encountered their future partners, Purba Sari and Ambetkasih, respectively, with their identities hidden, being covered by the black-monkey coat or being painted with a black mixture of soot and sap.

The Raffles story furnished some knowledge of contemporary social background. For instance, (1) fishermen installed traps in the river; (2) rice-growing was propagated; (3) a significantly large ship was used to travel along the southern coast of Java Island; and (4) various plays were performed in the feast at Pakuan.

Most of Pantun Sunda, including those cited above, were based on episodes of kings and princes during the period from Kendan/Galuh to Pajajaran kingdoms and, despite being written in poetic phrases, they were principally the kind orally told to public audiences. It was natural because the literacy of common people pervaded only after the beginning of the 20th century with the introduction of primary education, but it does not mean that no high-literary poems were written even when the number of readers was limited. A famous example was Bujangga Manik, a long poem of 1,575 octosyllable lines presumably written in the late 15th or the early 16th century. In short, the story was as follows [56]:

“Despite he was a prince of Pakuan, Ameng Layaran (alias Bujangga Manik) became an ascetic monk and travelled around Majapahit in Java, but once returned home sick for his mother. Although his mother urged him to marry Princess Ajung Laran who longed for him, he departed for another journey and reached Bali via Java. Having seen that Bali was highly populated, more than Java, he returned to the territory of Pajajaran and, after roaming around, settled halfway down Mt. Patuha [57] to create a sacred place. He erected a jewelled linga [58], built several pavilions furnished with a kitchen, a shed for firewood and a place for threshing, and completed his practice after nine years. In the tenth year, his body ended without illness, but his soul ascended to beautiful heaven.”

Although the story itself was rather simple, his high mental spirituality was mentioned in many parts of the poem. In addition, a detailed description was given on various scenes throughout the whole volume and the itinerary, particularly of the second trip, was minutely recorded, providing me with useful knowledge of contemporary manners and customs and topography.

In the scene of his visit to her mother after his first journey, for instance, the room where the mother stopped weaving and welcomed Bujangga Manik was situated in a high-floored mansion, decorated with a seven-fold curtain and furnished with a gilded Chinese chest. The cloth she was weaving was an ikat with cotton yarn dyed in red, blue and yellow. From a line of the poem, she was supposed to be an aunt of Siliwangi. When Jompong Laran (probably a relative lady) who had seen Bujangga Manik told Princess Ajung Laran that “he is well-matched for you. He is exceedingly handsome, more than Siliwangi, he is highly intellectual and speaks Javanese, etc.”, the princess presented a tray of betel with her love to Bujangga Manik by entrusting it to Jompong, a tray of betel that she carefully prepared with leaves of sirih (Piper betle), nuts of pinang (Areca catechu), lime stones, fragrant sandalwood, etc., all of the best quality, covered with a ceremonial cloth. The ships that Bujangga Manik took during his trips (from Pamalang, Central Java, to Sunda, and to and from Bali in the first and second journeys, respectively) were large junks [59], the original countries of her crew members having been various, depending on their expertise. On departure, guns were fired seven times, shawms were played, gongs and cymbals were tolled and sailors sung boat-songs.

A question remains about who the composer of this poem was. It would be almost certain that only the traveller himself was able to write, or dictate, the detailed itinerary with the names of mountains, rivers and villages. I should like to conjecture that the whole volume, including the scenes of the death of the hero and the ascension of his soul to the heaven, were composed by a certain prince named Ameng Layaran himself prior to the end of his life.

A set of four pieces of stone discovered in Cibadak village, forty kilometres south of Bogor, with an inscription of forty lines, recorded that the monument was erected on the 12th day of the white-half of the month, Kartica in the year 952 Saka (11th October 1030 Gregorian) by King Maharaja Gaped of Sunda who, according to Pustaka rajya rajya i bhumi Nusantara (The Book of Kings in the Land of Archipelago) , was the 20th King of Sunda who reigned 1030–42. Since the notice in the inscription was something like, “Fishing in the river in a region from one upstream point to another downstream point is forbidden”, it is my own view that such stone monuments might have been placed also in some other places. Since the language used was the Sunda Kuno (Old Sundanese), it is considered that the colour of Indian heritage seen in the age of Tarumanagara would have already faded out and that the Sunda Kingdom was the kingdom of Sundanese people [60].

Around that time, in Central Java, the Sailendra and Sanjaya kingdoms prospered and erected such magnificent temples as Borobudur and Prambanan, whereas no such fine monuments were left by Hindu kingdoms in Sunda probably because they had to frequently move their capitals suffering from floods and volcanic eruptions and had insufficient funds to build big monuments.

Old Hindu temples in West Java

The only one Hindu temple that remains in West Java is the well-known Candi Cangkuang discovered in 1966 by the lakeside of Bagendit in Leles village in the suburb of Garut[61]. Since a hot spa existed on a near-by mountainside, the lake itself was a popular resort ever since the old days.

When Marquis Tokugawa visited there in the 1920s, he wrote in his travelogue, Journeys to Java [62] , that his party was welcomed with angklung [63] music played by local children and offered flowers from lovely girls. I have visited this sightseeing spot twice in the last decades when the same atmosphere still remained.

When my friend and I crossed the lake on a small boat called a “sampan”, a candi about eight metres tall appeared. It was a typical Hindu-style temple with a motif of Semeru (Mt. Meru) just like candis in Prambanan in Central Java and Singasari in East Java. Although it was much smaller than those in Java, I thought the reassembling of scattered stone pieces must have been hard work, like the solving of a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. When we walked close to it, however, there were no reliefs such as those carved on the candis of Java. There was no Kala’s head [64] on the beam of the gate either. In the niche, there was a small stone statue of about one-metre height, which was recognised to be a carving of Siva sitting cross-legged on Nandi from the head of an ox seen underneath, although the face was not clear. The statue must be a pretty old one, as the surface was quite rough, due probably to the weathering, and its waist part was apparently broken and bonded, but the size was small for the space of the niche. (Above was the observation in February 2000 and, if not mistaken, the niche was empty when I visited ten years earlier.) Thus, there was no awe-inspiring atmosphere that one feels in old shrines and temples in general. Around there was no board to explain the history such that is commonly seen in other sightseeing sites. After returning home, I had a look in several books, but no detail of this particular candi was found.

|

Candi Cangkuang (with Prof. K. Kajiwara). Photographed by M. Iguchi, 2000. |

|

Statue of Siva in Candi Cangkuang. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 2000. The scattered papers are offerings of banknotes. |

A rumour said that what had actually remained was only the stone foundation of 4.7 m × 4.7 m square, which was estimated to have been laid around the 8th century and the candi itself was designed and built by someone of modern times. Then, I remembered that the shape of the candi was more or less similar to that of Candi Pawon near Borobudur in Central Java. Nevertheless, some stone building must have existed at the site of Cangkuang according to a book [65] in which it was written that the stone blocks found around there were re-used for Islamic tombs.

Relatively recently, I learnt that another ruin of candi existed in the vicinity of Cicalengka, thirty kilometres east of Bandung, and visited there. The excavation site was found in a small village called Bojongmenje, where we were received by Bapak M., a dilettante historian from Banten, who had been working alone ever since the discovery of the ruin in 2002. In the middle of the field of some one-quarter acre fenced with iron net was a stone foundation of five metres square, and several hundred stone blocks were piled up in a corner of the field, as well as in a work shed, in a disorderly manner. Among them were some pieces on which some patterns were engraved, although they were quite blurred by weathering. There was a special piece, a stone ball of about 15 cm diameter, which was supposed to have been the orb on the tower placed on a cubic block. Bapak M. told us that there was a small statue of Nandi (sacred bull), but it was moved to a museum in his home town for security reasons. He lamented that the authority did not give much support to his excavation.

|

The foundation (top) and stone blocks (bottom) of a candi discovered in Bojongmenje village, near Cicalengka, West Java. Photographed by M. Iguchi, January 2009. |

Around Cicalengka must have been the place where the Kendan Kingdom, founded in 516 AD by Manikmaya, a son-in-law of King Suryawarman of Tarumanagara, had existed for a period of one century until the capital was moved to Galuh in 612 AD. If the candi was the one built in that period, it must be pretty old, or even older than those candi remaining in Central Java. Later, I found an article that mentioned an archaeological view that the candi was the construction of the 7th–8th centuries [66].

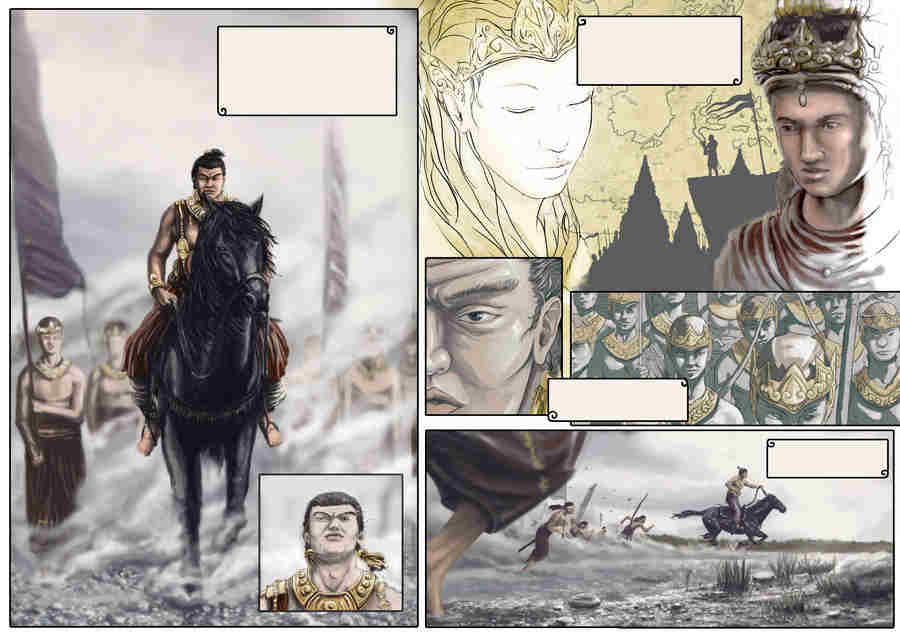

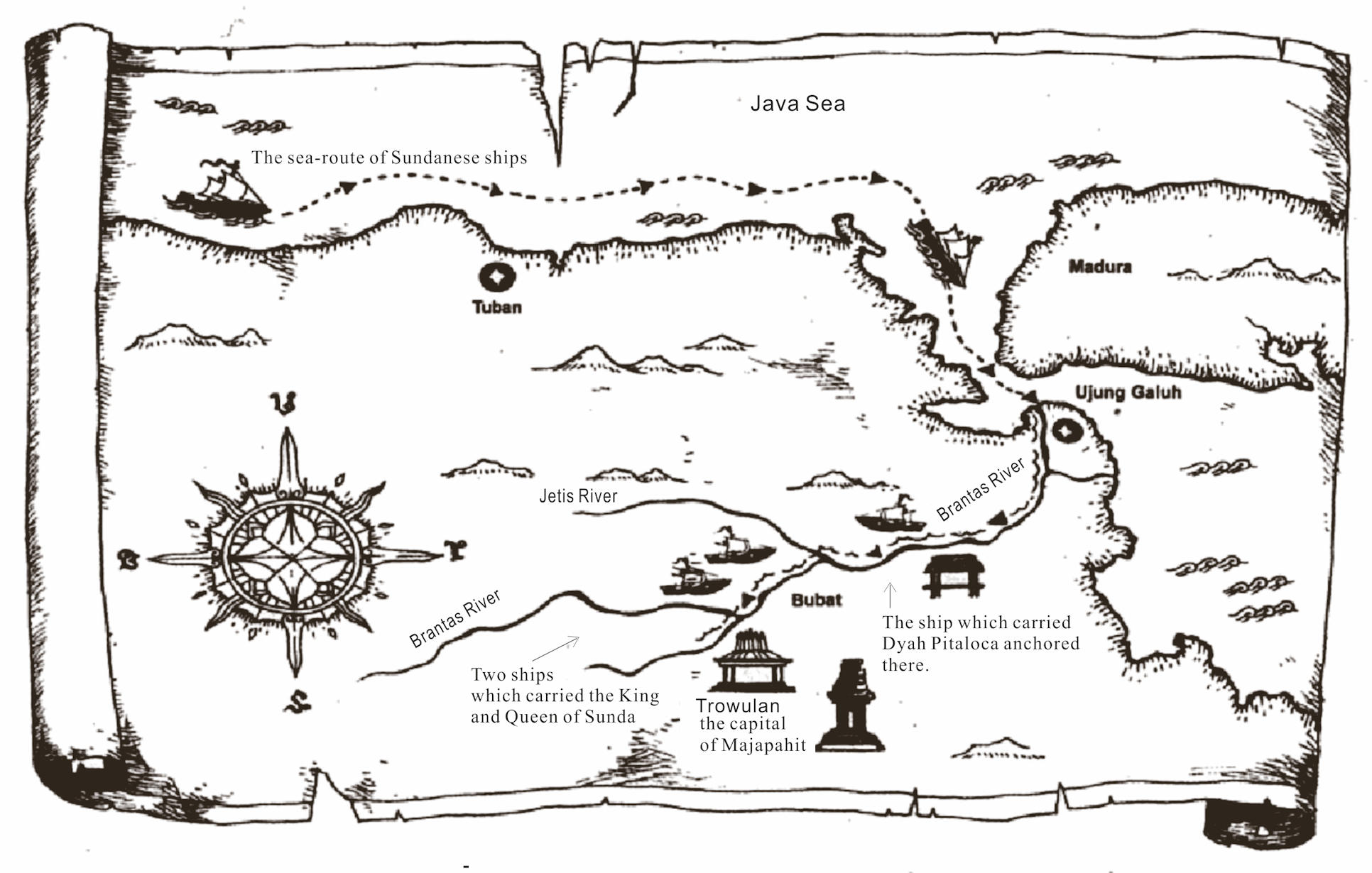

It was in 1357 when the capital of Sunda was in Kawali that an incident, which is still remembered as “The Tragedy of Bubat” among Sundanese people, happened. At that time, the Majapahit Kingdom with its capital in East Java was in the zenith of its prosperity under King Hayam Wuruk, with the aggressive service of Premier Gajah Mada (short name for Maha Padi Madah), ruling East and Central Java, and expanding its territory to Sumatra, Borneo and other outer islands.

When Hayam Wuruk, who was still single and looking for his consort, received a portrait of a renowned peerless beauty, Princess Dyah Pitaloka Citraresmi of Sunda, from a painter, Sungging Prabangkara, whom he had despatched to Sunda to draw her picture, Hayam Wuruk immediately fell in love with the figure in the picture and sent a messenger to Sunda to ask for the princess’s hand. The Sundanese side welcomed the proposal, but some royal family members objected to the request to conduct the wedding ceremony in Majapahit, because the visiting of the bridegroom’s side to the bride’s side was common at that time [67]. King Maharaja Linggabuana finally said it did not matter and started on a voyage to Majapahit accompanying Queen Dewi Lara Linsing, Dyah Pitaloka and some family members as well as some ministers and imperial guards, with a big fleet of 200 vessels and small boats, 1,000 in number. At the time of embarkation, they saw that the blue sea water turned to red, a bad omen, but sailed off the port and ten days later arrived at Bubat on the bank of Brantas River in the suburb of Majapahit’s capital. There, they were told by Gajah Mada, who hid an ambition [68] to conquer the whole Java Island and get the better of the king, that Dyah Pitaloka was not to be received as the queen but would be a tribute, and that the Sundanese kingdom should be a dependency of the Majapahit kingdom.

With no means of asking the true wishes of Hayam Wuruk, being surrounded by Gajah Mada’s army, King Maharaja Linggabuana decided to fight as a warrior rather than to be affronted. He told the queen and daughter to return to Sunda, but they said they would stay there. When the battle started, the Sundanese fought well, despite that they were much inferior in number. The king was a good warrior and beat many enemies, but the king and all Sundanese men died on the battlefield of Bubat. Having seen the disastrous scene, Dyah Pitaloka, Queen Lara Linsing committed suicide and the second queen of Sunda and wives of ministers followed [69].

|

Images of the Bubat War of a modern artist. Reproduced by courtesy of Mr. Gilang Kencono Nugroho, Bandung, from: http://browse.deviantart.com/?qh=§ion=&global=1&q=bubat. The persons on the left, top-left and top-right are Premier Gajah Mada, Princess Dyah Pitaloka and King Hayam Wuruk, respectively. Boxes are deliberately blanked by the artist to leave the contents to readers’ conjecture. |

Hayam Wuruk must have been truly wishing to marry Dyah Pitaloka and to establish a kinship with the Sundanese Kingdom. He, who at last realised the treachery of Gajah Mada, collapsed on the body of his deceased fiancée, which he found in the field and vowed that he would join her soon to be united with her forever. He sent a Balinese ambassador who had been there to be the witness of the expected wedding to Sunda to deliver his apology to Minister Eyang Bunisora Suradipati, King Linggabuana’s brother, who was in charge of the kingdom during the absence of the king. After conducting the ritual, Hayam Wuruk pined away and died shortly afterwards. After the magnificent royal funeral, which was held for one month and seven days with various performances, Gajah Mada, who was accused by the uncles of the king, meditated for a while and disappeared as if his body evaporated.

Above is the brief summary of a poem, called Kidung Sunda (Song of Sunda) [70], written around 1550 AD by an anonymous author and discovered in the modern age in Bali, to which some names of characters and some backgrounds were supplemented with reference to the descriptions in such other books as Pararaton ( Book of Kings)[71] and Carita Parahiyangan. A literary work, the poem includes some modifications in the light of the real history. In fact, Hayam Wuruk survived until 1389 AD, while Gajah Mada died in 1364 AD in Probolingo in the eastern province of Java, according to Desawarnana (also called Nagarakertagama) [72], which is reputed as the most reliable chronicle. With respect to the details of the story, there are various versions. [73] For instance, opinions split whether after the incident Gajah Mada retired himself or he was dismissed by the king. As to the origin of the incident, there seems to be a theory that Gajah Mada had just simply misunderstood Hayam Wuruk’s will to face the Sundanese, but it would be too sympathetic to Gajah Mada. It is also said that the cause of the death of Gajah Mada was an injury that he had suffered by Dyah Pitaloka who had joined the battle with a kujang (knife) inherited from the time of Tarumanagara.

The location of Sunda’s capital is not found in Kidung Sunda, but it must have been Kawali. They are supposed to have sailed downstream to the mouth of Citanduy River and turned around the coast of Java Island clockwise to the bank of Brantas River. It would have been possible to cover the distance of 1,000 kilometres in ten days, as the royal vessels were said to have been multiple-sail Chinese-style junks, which were common ever since the occasion of the invasion by Mongolians. [74], [74a]

Trowulan, the old capital of Majapahit

Once I visited the site of the old Majapahit capital, present-day Trowulan, near Mojokerto, forty kilometres south of Surabaya, where in an area of five kilometres square were magnificent gates, temples and bathing places of Hindu style, and where a huge water reservoir of some 400 × 200 metres [75] remained full of water. The excavation of the keraton was still continuing and the meditation room was just exposed. It was a small cell of about 1 × 3 metres, which looked unbalanced for the big building of over 1,000 square metres, but I thought it might have fitted the purpose and imagined the figure of Hayam Wuruk who would have sat and crouched in it after the carnage in Bubat.

In this old capital, one fact that was impressive to me was that most of the buildings were made not of stones but of fine bricks of 37cm × 21cm × 7 cm[76], proving that they had not only advanced technology of mass production but also a sort of industrial standard. Later, I found a similar observation inThe Malay Archipelago authored by Alfred Russel Wallace in 1869[77]. In The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores (Ying-yai Sheng-lan, 瀛涯勝覧, 1416), Ma-Huan (馬歡) who accompanied the great expedition of Admiral Zheng-He (鄭和) of Ming Dynasty, only wrote about the standards of volume and weight in Java (Majapahit) [78], but also the standards of length must no doubt have existed there.

|

Candi Pajang Tatu in the outskirts of Trowulan. Left: Total view, Right: Close-up. Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2009. |

| An excavation site of a building that was supposedly a palace of Majapahit time at Trowulan (left); A small cell which is considered to have been a meditation room (right). Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

The Trowulan Museum held a very large collection of stone statues, reliefs, ceramics, metal pieces and other artefacts, and a terracotta figure of Gajah Mada’s head caught my eyes. I murmured, “Does not his face look treacherous?” Was it because of a prejudice of myself who, having lived in Sunda for some years, was inclined to the Sundanese? When I asked the director of the Museum about the site of the Tragedy of Bubat, he corrected my words, saying, “Ah, the Incident of Bubat!”, and put a mark on my map. Indeed, for Javanese people, it was probably a small incident that occurred during the golden age of Majapahit. The field of Bubat behind the museum did not offer any image of old battleground and the air was peaceful, farmers’ houses standing here and there and vegetables growing under the tropical sun. In Desawarnana, it was written that tall buildings stood in Bubat and religious services and fighting competitions were held in the middle of the field, but no account was given on the Bubat War in this book, which assumed the nature of paean for the monarch.

|

A terracotta figure of Gajah Mada’s head part, held in Trowulan Museum. Photograph by Dinas Purbakala. Claire Holt papers, #14-27-2648. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, reproduced by courtesy of the library. |

Since I have repeatedly written “West Java of Sundanese people and Central and East Java of Javanese people”, readers might wonder why not all inhabitants in Java Island were not Javanese. In fact, I myself was quite astonished when, soon after I settled to live for the first time in Java Island in Bandung in 1990, a girl student who came to my house said, “My parents went to Java.” Despite that both Sundanese and Javanese descended from the same Southern Mongoloid stock and they were racially not different, they had little contact with each other from ancient times, as Europeans clearly distinguished Sundanese and Javanese people and, even in the 16th century, misunderstood that Sunda and Java were geographically two separate islands. Although 200 years have passed since the unified rule started under the Dutch administration and sixty years since the Republic of Indonesia was formed, Sundanese people still insist that they are different from Javanese and that West Java is the territory native to Sunda. Their consciousness seems to be as strong as, or even stronger than, those of the Scottish people against the English who are different in their origins[79].

|

Map of Java Island (Descripcao da ilha de Iaoa) Madrid 1615(?). By courtesy of Portuguese National Digital Library, reproduced from http://purl.pt/1442/1/P1.html. Note that the left-hand side is the north, and a waterway down between the West and the Central Java. While the north coast facing the Java Sea was detailed, the south coast was yet to be explored. “Dayo” indicated in West Java shows Pakuan, the capital of Pajajaran mentioned by Tome Pires in 1512. The position of “Mataram” in central Java is not correct. From the facts that Mataram was founded in 1584, that the Portuguese–Pajajaran Treaty was signed in 1522, and that Jayakarta was renamed from Sunda Kelapa in 1619, the original map is assumed to have been drawn in 1512-1584. |