Ancient Stone Monuments – The Prasasti of Tarumanagara

In a corner of the crossing of Salak and Pangrango Streets in Bogor, not far from the Botanical Garden is located Taman Kencana, a small park of about 100 metres square. In a green-rich environment, the park is surrounded by the old campus of Bogor Agricultural University’s Veterinary Department (former Veterinary School), the site of the Research Station for Rubber Technology where I used to work, a row of small shops, which sell foods and daily goods, and some old houses, and the park itself, covered with grass and a planting of flowers and trees. Thus, the park is not like alun-alun, or town-centre squares, that are found in many towns in Java Island, but a place of recreation and relaxation for neighbouring inhabitants, although it is often used for such a purpose as a polling station on the occasion of a general election.

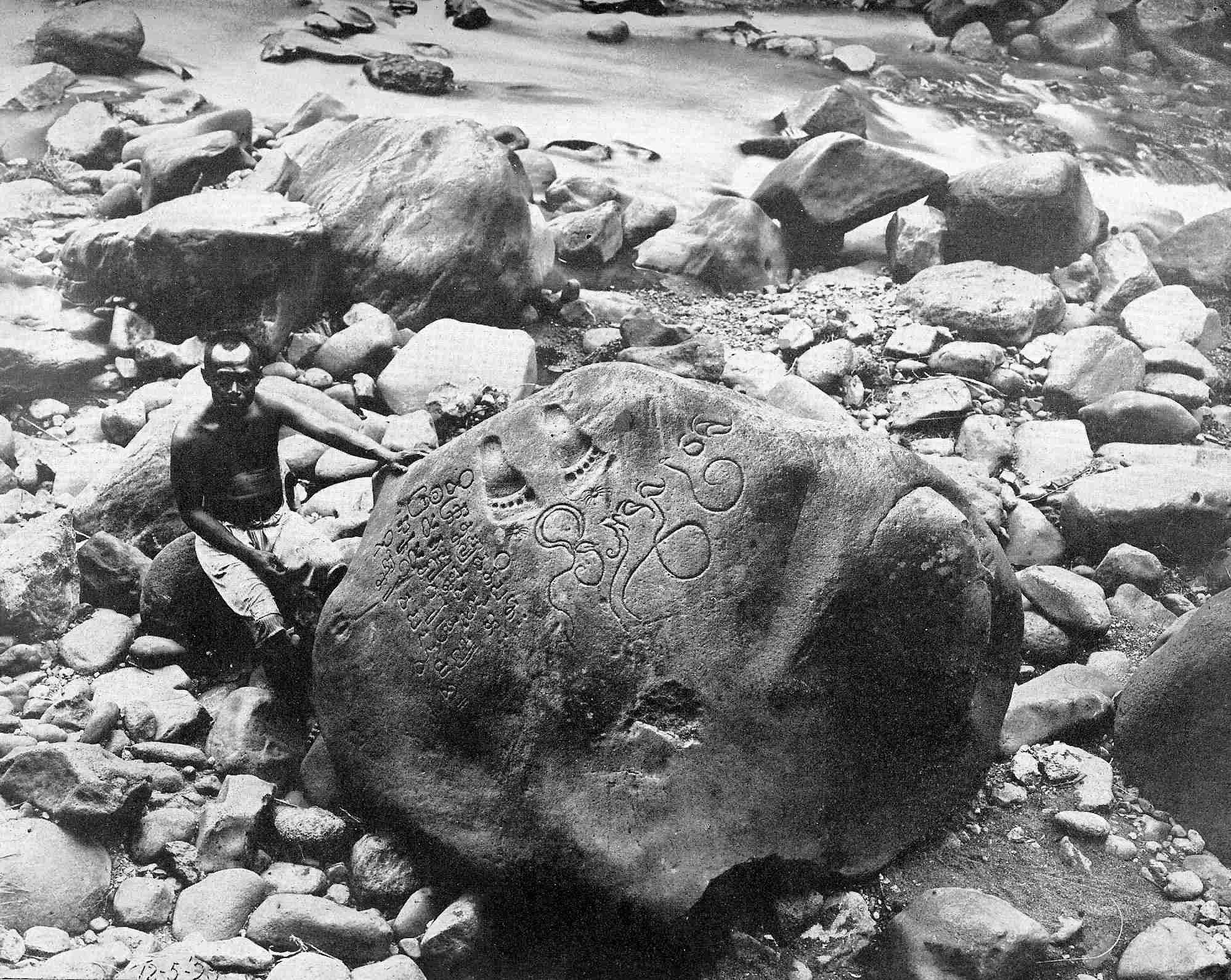

In the middle of the park, there was a stone-like object about four metres wide, on the smooth surface of which were inscribed a pair of human footprints and some pictorial letters. I was told that it was a replica of a stone monument of the Tarumanagara Kingdom, which prospered in West Java in ancient times. The real monument was found in a riverbed of Ciaruteun (Aruteun River) [1] in a suburb of Bogor and its existence was reported in the 1860s. It was the time when modern archaeological study had just started in Java and the stone caught the interest of contemporary researchers [2].

| Prasasti Ciaruteun. Reproduced from: W. F. Stutterheim, Pictorial history of civilization in Java. Translated by Mrs. A. C. de Winter‑Keen, The Java Institute and G. Kolff & Co., Weltevreden, 1926. |

The symbols inscribed were very similar to those used in the Pallava Empire, which prospered in India in the 4th–5th centuries, and the language was Sanskrit. The large symbols on the right-hand side of the footprints meant “The King Purnawarman of Tarumanagara”, decoded in early days and the strings of small symbols on the left-hand side were deciphered in the 1920s [3]. In English, it says:

|

Of the valiant lord of the earth, the illustrious Purnawarman, [who is] the ruler of the town of Taruma, [is] the pair of footprints like unto Vishnu’s. |

This suggests that Purnawarman was regarded and respected as the incarnation of the Hindu God Vishnu, or an existence with a similar divinity.

Ancient stone monuments are called “prasasti” in Indonesian language. As four more pieces of prasasti of this age have been found in the vicinity of Bogor, one in Tugu to the east of Jakarta, and one in Cidanghiang to the south of Banten in the west part of the Jakarta plane, the ruling of Tarumanagara is considered to have ranged over a fairly wide area [4]. In addition, stone axes and other stone tools that are regarded as the same age have been abundantly unearthed all over the Jakarta plane and a few pieces of copper plates, discovered within the same area. Two pieces of stone statues of Vishnu found in the neighbouring area of Karawan in the east part of the plane proved that Tarumanagara Kingdom embraced Hinduism [5].

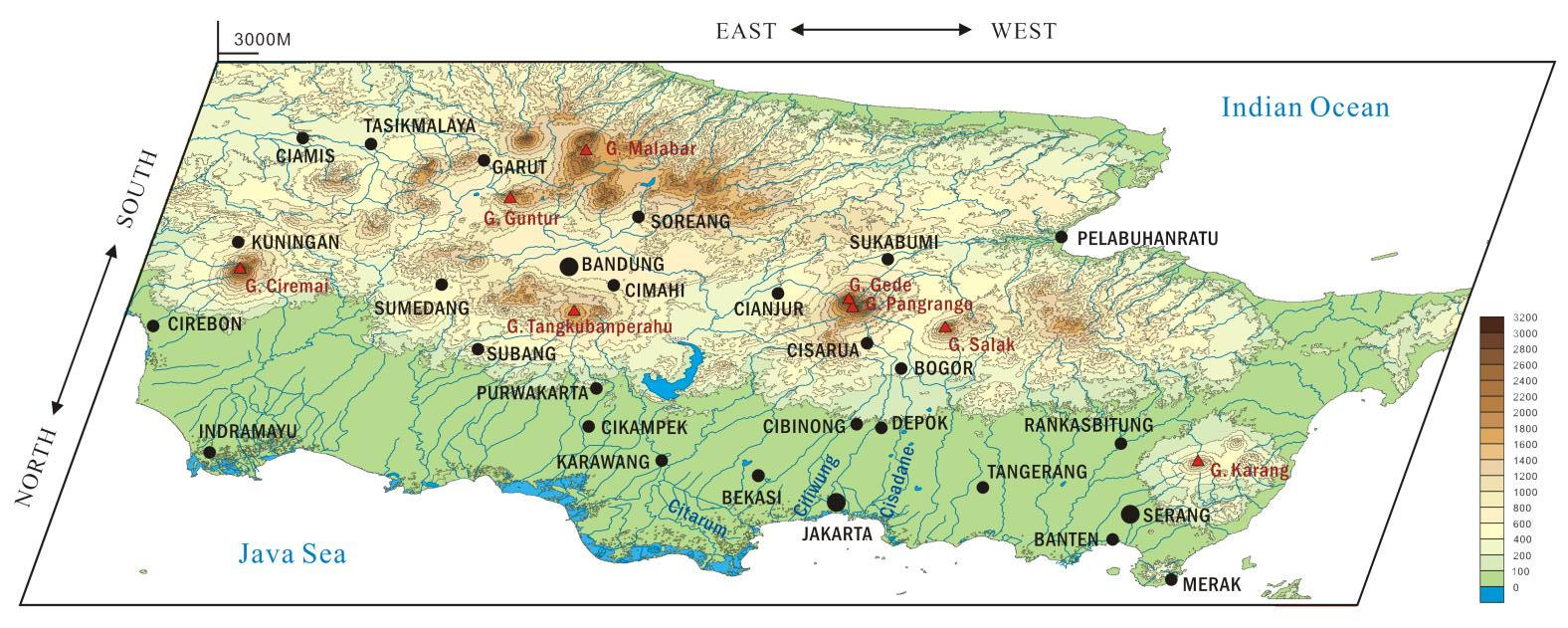

Let us see the records [6] on some prasasti that are quite diverse. “Prasasti Kebun Kopi” found in a coffee plantation and reported in the 1860s is alternatively called “Prasasti Telapak Gajah” because a pair of elephant’s footprints are carved. On it was inscribed:

|

Here appeareth the pair of the (brilliant) Airawata-like elephant of the Lord of Taruma [who is] great in strength and victorious. |

Airawata was the white elephant that was the vehicle of Indra, the God of War, whereas Nandi, an ox, was the vehicle of Shiva, and Garuda, an imaginary bird, was a carrier of Vishnu, the name of the last having been adopted as the national emblem and the name of national airlines of Indonesia. Since endemic Javan elephant (Elephas hysudrindicus) was extinct before historical time, the king and the followers would have brought their elephants from Sumatra or the continent.

| Prasasti Kebun Kopi. Reproduced from: Vogel, J. Ph., The earliest Sanskrit inscriptions of Java, Publicaties van den Oudheidkundingen dienst in Nederlandsch-Indie-Deel1, lbrecht & Co., Batavia 1925. |

A stone existed on a rock mountain, Pasir Koleangkak, in Jambu, 30 km west of Bogor, was known since the 1850s and called “Prasasti Jambu” or “Prasasti Pasir Koleangkak”. It had a pair of human footprints and a two-line verse:

|

Illustrious, munificent, and true to his duty was the unequalled lord of men – the illustrious Purnawarman by name – who once [ruled] at Taruma and whose famous armour (varman) was impenetrable by the darts of a multitude of foes. His is this pair of footprints which, ever dextrous in destroying hostile towns, is salutary to devoted princes, but a thorn in the side of his enemies. |

This stone monument, considered to have been erected after the death of Purnawarman, suggests that the king was excellent also as a warrior.

Prasasti Tugu formerly exposed only 10 cm of its head on the ground and local people offered flowers and burnt incense in its side. When dug out in 1879, it was revealed that it was a triangular stone of about 1-metre height and that on the surface of it was an inscription of a 5-line, 100-word poem recording the river works conducted during the time of King Purnawarman.

|

Formerly the Candrabhaga dug by the king of kings, the strong-armed Guru [the King’s father?], after having reached the famous town, went to the ocean. In the twenty-second year of [his] increasing, prosperous reign the illustrious Purnawarman – who shineth forth by prosperity and virtue and who is the ornament [lit. the banner] of the rulers of men – hath dug the charming river Gomati pure of water, long six thousand, one hundred and twenty-two bows [dhanus], having begun it on the eighth lunar day of the dark half of [the month of] Phalguna and completed it on the thirteenth lunar day of [(the white half) of the month of] Caitra. [The river] which had torn asunder the camping-ground of the Grand-father and Royal Sage, now floweth forth, after having been endowed by the Brahmins with a gift of a thousand kine. |

This description is ambiguous in some parts. Firstly, although Candrabhaga and Gomati were probably named after the rivers that existed in India, it was not sure to which rivers in West Java they actually corresponded. If they are assumed to be the rivers near the site of the stone’s discovery, one of them may be regarded as Bekasi River, but it is more plausible that they were Ciliwung and Cisadane, the two major rivers that ran through the area of the present Bogor and flew into the Java Sea. Secondly, it is doubtful whether it was possible to dig a river or a canal of such a length as 6,122 dhanus, which is assumed to be 7 miles (11.3 km) or 12 miles (22.9 km) within a matter of twenty-one days [7]. The relationship between Purnawarman to “the king of kings” and the Grand-father and the Royal Sage are obscure [8].

| Prasasti Tugu (Replica), Jakarta History Museum. Photographed with permission by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

The records suggest, however, that the rulers such as Purnawarman had made efforts to manage rivers, which often flood even today, and that Tarumanagara ruled the area as a solid kingdom.

Records in Old Chinese documents

Although these prasasti are the only direct evidence to prove the existence of Tarumanagara, many documents apparently concerned with this kingdom had remained in China [9]. In a book of the Later Han Dynasty, The Book of Southern Barbarians (南蠻西南夷列傳), was described that “in 131 AD, the king of Ya-diao (葉調), from the exterior of the Vietnamese coast, sent a mission to this dynasty: the emperor gave a gold stamp and a purple-ribbon medal to the king” [10]. Ya-diao was interpreted as the phonetic transcription of Jawadwipa (dwipa means island) and the king was assumed to have been Dewawarman of Salakanagara [11], a kingdom that had existed in West Java before Tarumanagara to be mentioned below.

In the early 5th century, a Buddhist priest, Fa Xian (法顕), from the Eastern Chin Dynasty, arrived in Jawadwipa on his way back to China from Ceylon, after a hard voyage of ninety days, and stayed there for five months. In A Record of the Buddhist Countries written in 414 AD, he wrote that “There were a large number of pagans [i.e. the native Sundanese inhabitants] and Brahmans but no Buddhist” [12]. Although the name of the kingdom was not explicitly given, the country is assumed to have been Tarumanagara.

A more suggestive description about Taruma was found in Sung Shu (The Book of Sung) [13] in that “in the 7th year of Yuanjia (元嘉, [430 AD]) a mission from a certain country, 呵羅單國, often read as ‘holotan’ in alphabet, which ruled Java presented gold rings, red parrots, Indian cotton fabrics, etc., and in the 10th year (434 AD) the ruler of the country, 毗沙跋摩, praised the great achievement of Emperor Wendi (文帝, [424–53])…” Even to the eyes of myself, a non-linguist, the name of the ruler (毗沙跋摩) looked to be the phonetic transliteration of Wisnuwarman, the 4th king of Tarumanagara who had succeeded Purnawarman in 356 Saka (434 AD).

What was the country that was phonetically transcribed as 呵羅單國 (Holotan or Karatan)? At that time, I could find no answer in the literature [14]. I asked several friends of mine in Bogor, but there seemed to be no place in West Java that sounded like “ka-ra-tan”, the pronunciation obtained from a Chinese–English dictionary. When I visited and asked Mrs. M., a Chinese-Indonesian friend in Jakarta, she told me, after thought that the pronunciation could be “a-lo-tan”, or possibility “a-ro-tan”, as the sound of the middle character (羅) could be “ro” as Roma was transliterated as “羅馬”. On my way back from her house, I was humming “a-lo-tan” or “a-ro-tan” and an idea flashed into my mind. It must be "Aruteun" of Ci-Aruteun, where the “Prasasti Ciaruteun” and the “Prasasti of Kebun Kopi” were found! Literally, Ci- is just a prefix for water in Sundanese. In Ciaruteun, I have seen several pieces of large cubic stones of about 50 cm square, which must have been the foundation stones of a palace or some magnificent building, as described below. If the above interpretation is correct, it leads to an assumption that the capital of Tarumanagara would have existed in the present-day Ciaruteun and the country itself was also called “Aruteun country”, and that the despatch of the mission to Sung was done during the reign of Purnawarman and continued in the era of Wisnuwarman.

Several days later, I spoke about my theory to Mrs. E., of the National Museum of Indonesia to whom I pay great respect as my teacher of Javanese history and culture. Although she was a person who was cautious in the interpretation of historical matters, she appreciated my idea and told me, “It would be complete, if some other supporting facts were available.”

Don't be too sure of yourself! A few years later I was a little disappointed to find a description in a book [15] that the word Holotan (呵羅單) in the Chinese chronicle must be the phonetic transcription of Aruteun and that the capital would have been located somewhere around Ci-Aruteun, although no mention was made of the remaining large foundation stones that I thought were important evidence for determining the location of the capital. The statement in the same book that “Aruteun was the earliest kingdom in [the island of] Java, which had existed before Tarumanagara”, is open to question. In common-sense terms, I believe the Aruteun country (呵羅單國) in The Book of Sung was more likely another name of Tarumanagara.

Among the presents to Sung, Indian cottons must have been imports, whilst gold rings might have been domestic artefacts as there were gold mines in West Java. As wild parrots must not have been in the Island of Java, red parrots as presents would either have been captured in an eastern island or their offspring [16]. In any case, it is interesting that this bird, which imitates the human voice, has been a pet since ancient times.

The fact that the Aruteun country must have possessed excellent ships that enabled them to frequently send missions to remote China as early as in the 4th century is a little surprising, whilst many Japanese embassy fleets to the Tang Dynasty China in the 7th–8th centuries were frequently wrecked on their much shorter sea-route.

In China, the name of Tarumanagara appeared in documents of later centuries (e.g. in The New Book of Tang (新唐書) and The Encyclopaedia of Statecraft (通典) as "Ta-ro-ma (多羅磨)” [17] ), implying that the country continued to have existed well into the 7th century.

Although documents were scant, the history of ancient kingdoms was orally passed down from one generation to another even up until after the religion changed from Hinduism to Islam. A series of chronicles, calledNaskah Wangsakerta, compiled in the 17th century in Cirebon [18] is quite informative and rated as important resources. Let us briefly review the history after the Salakanagara Kingdom [19].

Salakanagara, the oldest country

Salakanagara, also called Rajatapura, which was marked as Argyre in the world map of Ptolemy (150 AD), is said to have been founded by Dewawarman who came from Pallava, India, to Java and was married to the daughter of the local ruler, Aki Tirem (alias Aki Luhur Sang-mulya). The kingdom with its capital at Teluk Lada (in the present-day Pandeglang County) ruled the area for over 200 years until 358 AD, when Jayasinghawarman, the son-in-law of Dewawarman VIII, founded Tarumanagara in the eastern part of the territory, and probably continued to exist for a certain period as a regional kingdom. Jayasinghawarman himself was a high priest in Salankayana, a dependency of the Pallava Empire in India, but took refuse in Java, as his homeland was conquered by the Magada Kingdom. Purnawarman was his grandson. The fact that the stone inscription was written in accurate Sanskrit with beautiful Pallava letters [20] is reasonably understandable from such background of his family.

It is said that Jayasinghawarman, the founder of Tarumanagara, who passed away in 382 AD, was interred at the bank of the Gomati River and that the second king, Darmayawarman, who died in 396, was interred at the bank of Candrabhaga, but the places are unknown, as mentioned before. During the reign of Purnawarman, from 395–434 AD, the kingdom was most prosperous with forty-eight vassal kingdoms ranged from Salakanagara to the west and Purwalingga (the present-day Purbolinggo, Central Java) or Cipamari (Breves River in Central Java) to the east. In 397 AD, he constructed a new capital, Sundapura, near the coast, which is supposed to be the later Sunda Kelapa, in the present-day North Jakarta [21].

In 526 AD, Manikmaya, a son-in-law of the 7th king, Suryawarman, founded a small new kingdom at Kendan in the eastern part of the territory (around the present-day Cicalengka, east of Bandung), and in 612 AD, Wretikandayun, a great-grandson of Manikmaya, erected Galuh Kingdom in a far eastern area, near the present-day Ciomas. Tarumanagara itself was attacked and defeated around 650 AD by Sriwijaya, a strong kingdom based on Sumatra, and became weakened. In 669 AD, the 12th King Linggawarman of Tarumanagara devolved the kingdom to his son-in-law, King Linggawarman of Sunda and the history of Tarumanagara ended. What was the reason why the family of Jayasinghawarman chose Java as the place of refuge? Beside the facts that Salakanagara founded by Dewawarman from the same ethnic origin had existed and that the soil of the island was quite fertile, spices abundantly available around the archipelago might have been an attraction. They included clove and nutmeg indigenous to Molucca, which was to be called in later centuries Spice Islands. Needless to say, spices from Asia were indispensable as preservatives and deodorisers of meats, also in Europe, before the emergence of modern storage methods, as the cutting off of the traditional trade route via the Middle East by Ottoman Turks in the 15th century [22] urged the Portuguese, the Spanish and the Dutch to explore new routes to reach Asia.

Since the arrival of Jayasinghawarman to Java coincided with the golden age of the Roman Empire where demands for spices must have soared, the export of those items would have greatly contributed to the finance of the kingdom, whether or not they had directly participated in the spice trade that was traditionally undertaken by Indians, Arabs and Phoenicians.

Among special products of Java would have been indigo, as “Tarum” of Tarumanagara as well as of Citarum, the biggest river in West Java, meant indigo. Probably, the dye was produced in large quantities to represent the name of their country, already at that time. In fact, before the synthetic indigo became common in the beginning of the 20th century, Java was the leading supplier of natural indigo to the world market. Just for information, the Javanese indigo is obtained from a plant of the Pea or Pulse Family (Indigofera tinctoria L), and is different from the Japanese indigo, “Ai” from Buckwheat or Knotweed Family (Polygonum tinctorium).

Immigrants from overseas to Java

With regard to the relationship between the immigrants from India and the native Sundanese people, Fruin-Mees wrote her view in her book9 as, “Although the newcomers from India were culturally superior to the Sundanese, they were characteristically not the people who tried to force others to adopt their liberal arts. It was probable that they did not much associate but rather co-inhabited with Sundanese who held their ancestor worship, and the inter-marriage were rare. According to their caste system [23], the natives would be regarded to belong to the lowest Sudra class, but the Indians did not rule them by force. The Sundanese themselves were not well developed to adopt the high-level religion and culture.” On the other hand, in a school textbook authored by Eijkman and Stapel [24] in the same age, it is described quite differently, as follows: “It was sure that the Hindu kingdoms (such as Tarumanagara) were founded in a peaceful manner. Many immigrants married with Indonesian women and the two races merged. The merger of the natives’ manners and customs and the Hindu culture and religion became evident after the 8th century, as seen in the remains of Hindu-Java temples in Java [25] .”

While I was conscious of this conflict for several years, a solution was discovered in a volume of the modern translation ofPustaka rajya rajya i bhumi Nusantara(The book of kings in the land of archipelago) [26], which I had happened to find in a small library of Sri Baduga Museum in Bandung. There were lines, “Among those who came to Java (Aji Saka and entourage) from Bharata (India) were traders, officials and religious leaders”, “They hoped their wives and children could live peacefully there”, “Sang Dewawarman from Pallava was friendly with the residents of coastal communities in West Java, Pulau Api and the southern part of Sumatra Island”, etc. Despite that they had accompanied their families, intermarriage is considered to have been also common. Not to mention the expedition of Alexander the Great, when we look back, the overseas exploration of Europeans, the majority of those who came to Asia and other areas were men, at least until the emergence of safe steamers, as the voyage across oceans was so hard and dangerous for women that they had to find their partners among local women, unlike those people who emigrated to North America of relatively short distance and those to the remote part of South America (Argentina and Uruguay) and Australia in the later centuries. Although how many Indians came to Java in the 4th century and earlier is not certain, the number of women is considered to have been relatively smaller. It is hard to imagine that the pure blood was maintained for the long period of 300 years in Tarumanagara in which twelve kings reigned, although it could have been possible in the early few generations.

In the Kutai-Kurtanegara Regency in East Kalimantan (Borneo), some seven pieces of prasasti with Pallava scripts, which were similar to those on the prasasti of Tarumanagara, were found. They recorded in Sanskrit that a certain great king, Mulawarman of Martapura, or Martadipura, had dedicated twenty thousand cattle to Hindu gods and priests, observed rites, the names of his father and grandfather were Aswawarman and Kundungga, respectively, the latter being the founder of the kingdom, etc. From the characteristics of the scripts, the kingdom is assumed to be older than Tarumanagara and the first kingdom in the East Indies. From the similarity of the end part of the names, the royal family is considered to have originated from the same ethnic group as of Tarumanagara, which emigrated from India. The kingdom is widely called Kutai Kingdom, named after the KutaiKurtanegara Sultanate established in the 16th century [27], and the original name, Martapura, is rarely seen even in academic books, let alone textbooks. The name, Martapura, is never seen in Japanese books.

My wish to visit the home of the old kingdom was nearly realised at last in 2007, but there was no chance to see the remains. When I and my friend arrived at Mulawarman Museum in Tenggaron, driven one hour up along Mahakam River from Samarinda by Dr. Mrs. W., of Mulawarman University, which was also named after the great king, the 19th-century Dutch-style building in the sultan’s palace was unfortunately under renovation and only the sounds of hammers were heard. To go to the place where the prasasti were found, I was told that a voyage of two days and nights on a boat upstream of Mahakam would be required. Mrs. W. sympathetically told me that the prasasti housed in this museum were mere replicas, the real pieces having been moved to the National Museum in Jakarta. Looking at the stream of the great Mahakam River, which was as wide as 500 m and full of water, I had an image of the ancient kingdom in my mind and felt happy even to be there. Mrs. W. who came from West Java had rich knowledge about Tarumanagara as well as Martapura. As to the reason why the ancient Indians had come to settle in such a far away place in East Borneo, she said that it was located on the sea-route to China and they would have used it as a trading point. I also learnt that gold used to be produced in East Kalimantan, whereas major products now are woods and petroleum.

|

One of Prasasti Mulawarman (Replica). National Museum of Indonesia. Photographed with permission by M. Iguchi, January 2009. |

The history of this area after the time of Mulawarman until the rise of the Islamic kingdom in the 17th century is completely unknown. In the 17th century when Admiral Cornelis Speelman of VOC (the Dutch East India Company) attacked Gowa Kingdom in Celebes and Sultan Hasanuddin was defeated with the fall of Macassar in 1667, several thousand Buginese who did not want to surrender exiled to Kutai across the strait. The sultan of Kutai warmly accepted them and gave them land where a town called Samarinda, literally “equal treatment”, was born. The date, 21st January 1668, has been adopted as the anniversary of the present city of Samarinda. Is it because of this tradition that we do not hear of any ethnic issues in this area, despite that the 600,000 inhabitants of Samarinda comprise not only of Kutai and Bugis but also Dayak from the interior of Kalimantan and other races from other islands? The atmosphere of the departments in Mulawarman University looked peaceful with no factional discord.

The genuine piece of Prasasti Ciaruteun, mentioned in the early part of this chapter, was moved in 1990 from the riverbed where it was found, and placed under the shed on a near-by bank. One-and-a-half-hour drive from Bogor, the location is in a typical West Java village among banana and cassava fields. When I and colleagues visited, a gentleman who was entrusted as the caretaker of the remains kindly guided us. The stone monument lay in the middle of an open building surrounded by an iron fence under the roof of which appeared to be the same as its replica that I saw in the park in Bogor. I was quite shocked to find extraneous graffiti of dates and initials inscribed in modern characters on several parts of the stone, and realised the reason why the authorities decided to move it to a safe place. There was a noticeboard saying, “Those who damaged the article are imposed a fine of one hundred million rupiah!” From the huge amount, which was roughly five million yen (at that time), one can guess how important the stone monument was for the Ministry of Education and Culture, Indonesia. According to the caretaker who was involved in the evacuation operation, the whole work was conducted only by manpower, as bringing heavy machines in the heavily vegetated bluff was impossible. Since the stone was as heavy as over ten tons, it took six months and ten people to finish, and on some occasions it could be moved only 8–10 cm a day. Later, I incidentally saw some photographs that depicted the operation in Museum Taman Prasasti (Stone Monument Park Museum), Tanah Abang, Jakarta, and thought over the hard work achieved by the caretaker and his colleagues.

|

A shed, which holds Prasasti Ciaruteun. A noticeboard is seen in the front-left. Photographed by M. Iguchi September 2006. |

|

Evacuation operation of Prasasti Ciaruteun. A picture reproduced at Museum Taman Prasasti Tanah Abang by permission of the authority by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

Prasasti Telapak Gajah (Stone Monument of Elephant’s Footprints) was found 200 metres away from the site of Prasasti Ciaruteun. We were told that it was the original place and on a pillar of the shed, which had been built to enclose the stone, was the same noticeboard. In the surrounding field, coffee trees were no longer there, having been replaced by cassava plants, despite the fact that the stone monument still bears the alternative name, Prasasti Kebun Kopi.

Next, we were guided to a place where we saw four pieces of stone of some half a metre diameter. Two of them embedded in the ground had ten-odd holes of 6–7 cm diameter on the flat surface. A young colleague of mine, Mrs. R. smiled and said, “Oh, dear! This is congklak! I used to play it when I was a child.” The intellectual game called congklak in Sunda, alternatively called Dakon in Java, is still popular among children in Indonesia. Although a different theory says that the origin of the game was not in India but somewhere in Africa, it is certain that it was the Indian people who founded Tarumanagara who introduced it into Java Island. It was amusing to imagine that ancient people were playing the game around these stones.

|

Play arena of congklak of Tarumanagara Age. Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

Also interesting were several pieces of granite stones of about 50-cm cubic shape, with a hollow of about 40 cm square and 5 cm depth on one of their surfaces, laid under the eaves of the caretaker’s house. Several more of the same type of stones were found scattered in the near-by banana field. The stones must have been the foundation stones of a building, and judging from the size of pillars to fit the square hollow, the building was considered to have been a very big one. I thought over the possibility that the palace of King Purnawarman would have stood there. The guide told us that the name of Darmaga village halfway from Bogor, well known as the site of the new campus of Bogor Agricultural University, would have origins from King Dharmayawarman, the predecessor of Purnawarman.

|

Stone blocks that are supposed to have been the foundation stones of a large construction of the Tarumanagara Age. Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

In the early part of this article, concerning the replica of the Prasasti Ciaruteun found in Taman Kencana in Bogor city, I wrote, “there was a black stone…” in the past tense. In fact, when I revisited the park after several years, the replica was not there and a lamp pole to light up the park in the night stood in the same spot. People around there told me that the monument was removed a few years ago, but none of them knew its whereabouts. When a friend of mine enquired on my behalf to the district’s sightseeing office, they answered, “The monument was destroyed and removed because it was obstructive. It was a mere ornament, prepared from glass-fibre and resin, to decorate the park”, to my disappointment. The demolishing of valuable structures by ignorant officials often happens anywhere and I remembered the case [28] that the famous Harmonie Building in Jakarta, constructed in the early 19th century by a native contractor, was destroyed and removed in order to widen the road and provide an automobile parking place. Although I had lived in the neighbourhood of the park for three years, I had not taken a picture of the monument, because I had never anticipated its disappearance. I do not know how many replicas were prepared, but I still believe it was one of them. In any case, it was the very thing that induced me to study the ancient history of West Java.

Those people who find it difficult to visit Ciaruteun village can see its replica, as well as the replicas of other prasasti from Kebun Kopi, Tugu, etc., in the Jakarta Historical Museum (the old city hall of Dutch East Indies period) in Taman Fatahillah, North Jakarta. They are extremely fine replicas that one would believe to be the real ones, if not told. The National Museum, in Jalan Merdeka, Medang Meredeka Barat, Central Jakarta, housed numerous historical treasures collected from all over the Indonesian archipelago. The new building, which was opened in November 2006, has floors designed to display their collections from the aspect of culture, technology, etc. When I visited there prior to the opening by courtesy of my friend, a curator of the museum, a corner was being prepared to show the development of scripts in Indonesia from the time of Kutai and Tarumanagara kingdoms to the modern time. I admired the efforts of epigraphers who were studying those documents, which to me looked to be mere strings of curious symbols to the eyes of a non-professional, supposing that the process of the change from the Sanskrit to the Javanese and the Sundanese scripts would have been similar to that in Japan where hentaigana (intermediate cursive-style Japanese scripts) was born from cursive-style Chinese letters and evolved into hiragana (present-style Japanese scripts).

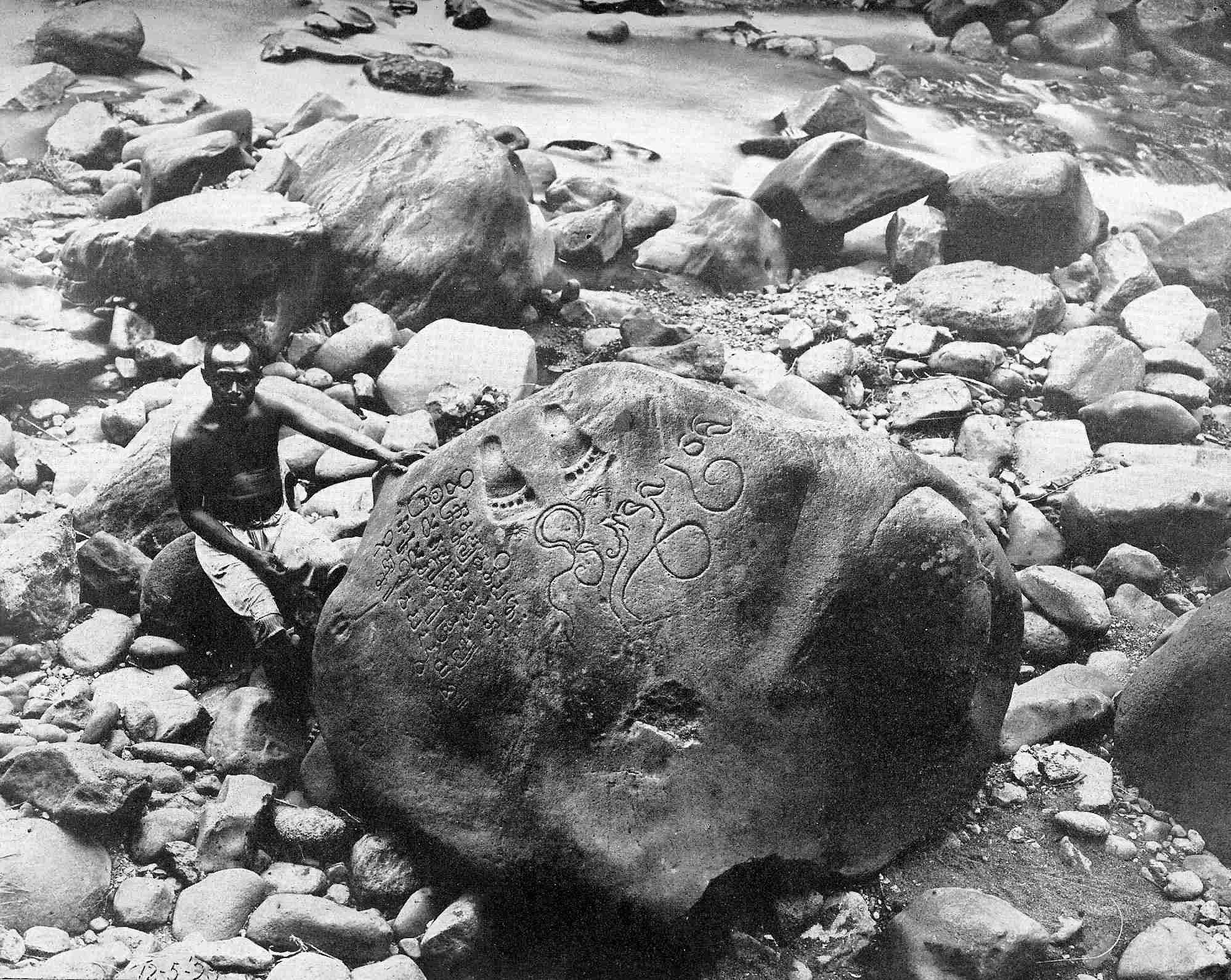

The mountainous district between Mt. Gede/Pangrango to the east and Mt. Salak to the west is an exceedingly pluvial area in Java Island, which belongs to the tropical rainforest climate, as Bogor is called Kota hujan (Rain city), the annual precipitation being over 2,500 mm. According to my experience, rain comes at least once every three days even in the dry season (normally April to September) and, in the wet season (October to March), it is not rare to miss sunshine for one week. The rain is almost always accompanied by a thunderstorm, as the Guinness Book of Records notes the city has the “most days per year with thunder” (322 thunderstorms/year) [29]. The lightning is so intense that many big trees in the Botanical Garden and those lined in the streets are frequently split. Since powercuts for half an hour are not unusual even with modern lightning-protection facilities, candles and lanterns are the necessities of houses, and private power generators are equipped in many offices and hotels. During my stay in Bogor, I had my computer modem damaged once or twice by lightning surges, which entered from the telephone line, and I learnt that unplugging the cable when the sky was covered by dark clouds was the best measure as the normal surge arrester was ineffective. As the water precipitated on the mountains and fields poured into the Ciliwung and Cisadane rivers, soil and water conservation was a big issue for the government ever since the Dutch time, or the era of the ancient Tarumanagara Kingdom. While the damage in Bogor located in the middle basins of these rivers was not considerable as roads were temporarily turned into rapids, the muddy water turbid with eroded volcanic soil ran down to Jakarta to cause disastrous floods once every several years.

|

A bird’s eye view of the middle part of West Java. (View angle= 45°) Contour lines were obtained by QGIS geographic programme with SRTM 90m Digital Elevation Data, Srtm_58. Data of rivers and lakes were obtained by Diva-GIS with "IDN_water_lines" and "IDN_water_area", respectively. |

Nevertheless plenty of water containing all sorts of minerals from volcanic ash has been a Heaven’s blessing for agriculture from ancient times, allowing Java Island to become the most densely populated area in the world. In West Java, the hills around Mt. Gede/Pangrango are extensively cultivated for growing rubber, tea and other plantation crops, as well as fruits and vegetables for daily consumption, whilst fertile paddy fields develop in the peripheral plains. Cianjur located to the east of the mountains is famous for producing the best quality rice in Indonesia, being equivalent to the Uwonuma district in central Japan. [30]

Tropical Java has no snowfall, but hail, locally called hujan es (ice rain), does come often as broadcast by television or reported in newspapers. It was my experience of twenty-four years ago when I was alone driving the ascending road of Jalan Cihampelas in Bandung on a rainy night that some small grains, glittering like diamonds in the dim street light, hit the windshield of my car. The traffic was sparse in those old days. Wondering what they were, I pulled off the road, picked up the grains on my palm and finally recognised that they were no other than grains of ice! [31]

During my stay in Bogor, there was an interesting event. In an evening after the rainy season the outside surface of the glass window of my house was covered with numerous insects of beige colour with transparent wings and many of them intruded into the room through the cracks. Turning off the light, I went out and saw the night light of the garage dimmed, flocked by the insects, whilst I was busy for shaking off many of them adhered to my white shirt. Soon a flock of bats which must be those inhabited in the Botanical Garden 200 metres away came to my garden and started to flutter about in the air in a height range from just above the ground to the level of eaves, how they knew the event unknown. On the wall and sash were dozens of white tokey (Latin: Gekko gecko) of 15 - 25 cm long, despite only a few of which were usually seen, crawling about to catch the insects, whereas on the ground were a number of toads jumping around in an unbelievably swift manner. The drama of nature finished within a matter of half an hour and the window and wall were cleaned. In the morning, small ants were collecting the small fragments. A friend taught me that the insect, measuring about one inch wide, is a kind of winged ant, locally called laron, and that the larvae which had lived in the soil emerged altogether in that night. Although all of the insects apparently became the prey of other creatures, a few of them must have successfully coupled and laid eggs to maintain the species. According to the friend's mother, during the last world war some Japanese soldiers who came to occupy Java from French Indochina or elsewhere were joyfully eating laron, removing the wings and frying in a pan. Since such a food is not in Japanese cuisine, they must have learnt it in their former place (This paragraph is new in this web-version).

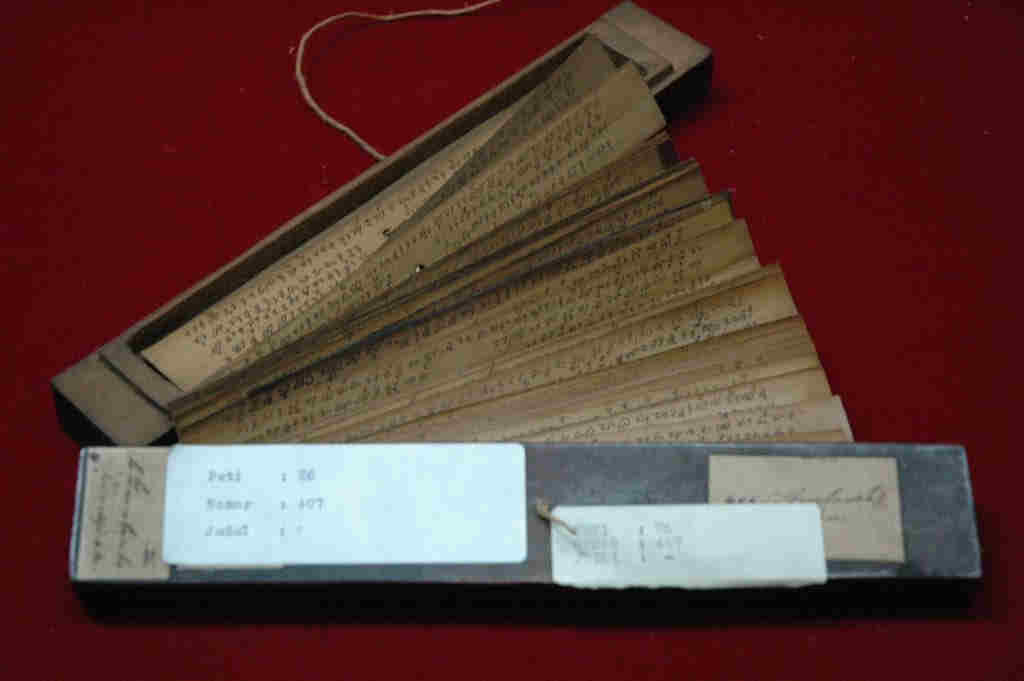

It is a matter of debate why documents other than stone inscriptions remained in Java. In old days before paper was invented in the 1st century BC by Cai Lun in the Later Han Dynasty spread, parchment or sheepskin was used in Europe as the materials for recording, whereas the sheet traditionally used in Java was “lontar” [32]. It was prepared from the leaves of lontar or siwalan palm (Borassus flabellifer) by cooking them in herbal water, cutting in the shape of a strip, and pressing, on which letters and often illustrations were engraved by means of an iron pen, and filling the scratch with a compound of soot and oil. The strips were bunched like a Venetian shade. Such materials themselves were not the kind that was durable for centuries in the hot and humid tropical climate, but it would have been possible that they were buried under the strata formed by volcanic ash from Mt. Salak to the west and Mt. Gede/Pangrango to the east of Bogor, which were both quite wild and frequently erupted. Thus, not only documents but also buildings were probably embedded under the earth, and only stone monuments that were washed by rain and river water appeared to the eyes of today’s people.

|

An example of Lontar document. Reproduced from: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Naskah_Sunda_Lontar.jpg (Contributed by Aditia Gunawan). The legend says it is an old Sundanese document, but the time is unknown. |

Volcanic eruption in ancient time

Mt. Krakatau or the Island of Krakatau located to the west of Java Island in the Strait of Sunda is also famous for a major eruption in 1883. In the article, entitled “The earlier eruptions of Krakatau”, contributed toNature, Prof. Judd introduced a description in The Book of Ancient Kings (Pustaka Raja Purwa), held in the library of Solonese court, which recorded a gigantic volcanic explosion of ancient time [33].

“In the year 338 Saka [i.e. 416 AD] a thundering noise was heard from the mountain Batuwara [now called Pulosari, in Banten], which was answered by a similar noise coming from the mountain Kapi, lying westward of the modern Bantam. A great glaring fire, which reached to the sky, came out of the last-named mountain; the whole world was greatly shaken, and violent thundering, accompanied by heavy rains and storms, took place; but not only did not this heavy rain extinguish the eruption of fire of the mountain Kapi, but it augmented the fire. The noise was fearful and, at last, the mountain Kapi with a tremendous roar burst into pieces and sunk into the depths of the earth. The water of the sea rose and inundated the land. The country from the east of the mountain Batuwara, to the mountain Kamula [now called Gede, to the east of Bogor], and westward to the mountain Raja Basa [in Lampung, in the southern part of Sumatra] was inundated by the sea; the inhabitants of the northern part of the Sunda country to the mountain Raja Basa were drowned and swept away with all their property.

“After the water subsided the mountain Kapi and the surrounding land became sea and the Island of Java divided into two parts.

“The city of Samaskuta, which was situated in the interior of Sumatra, became sea, the water of which was very clear, and afterwards was called the Lake Sinkara. This is the origin of the separation of Sumatra and Java.”

The Book of Ancient Kings was said to have been written by Ranggawarsita III with reference to some traditions or older documents. The same story of Krakatau’s eruption was written more in detail in a book authored recently by Prof. Purwadi [34]. An abridged translation is as follows:

“The following story was based on the Serat Mahaparwa [the story of Mahaparwa] authored by Empu Satya in 851 Saka [929 AD during the era of Kediri Dynasty].

“Once, God came from the heaven of Mt. Tengguru [Himalaya] to an island spanning from Aceh to Bali and named it as Java, after Dawa, which meant ‘long’. In 78 AD, a Brahmin, Aji Saka, was sent from India to Java and the year became the first year of Saka Calendar. He opened the forest of Mount Hyang and settled there with his real name, Empu Sengkala. Then, the sultan [35] of Rum sent 20,000 families to settle there, but due to epidemics, the number of families gradually decreased to 2,000, to 200 and finally to 20. In response to Empu Sengkala’s entreaty, the sultan gathered another 20,000 families from Keling, Ceylon and Siam and sent them to Java. After the death of Empu Sengkala, Java had no king. In 102 Saka [160 AD], gods in India despatched a group of saints, led by Resi Mahadeva Buda, to Java. They were welcomed by the inhabitants and restored the kingdom at Medang Kamulan.

“In the era of Sri Maharaja Kanwa in 329 Saka [407 AD], there was an incident when his daughter Dewi Srigati was kidnapped by Prabu Karungkala of Pidana [in Sumatra], although she was subsequently rescued by Raden Sengkan who later became her husband. In exasperation, Sri Maharaja Kanwa crushed the Pidana Country and destroyed Prabu Karungkala. Then, Prabu Sangkala, the king of Samaskuta [in Sumatra], a brother of Karungkala, no longer acknowledged the authority of Sri Maharaja Kanwa. In 338 Saka [416 AD], Sri Maharaja Kanwa attacked the Samaskuta Country and destroyed Prabu Sangkala.

“After that, Sri Maharaja Kanwa headed to Mt. Pulosari [in Banten] and killed Resi Prakampa, the father of the brothers, suspecting the latter might have been behind the whole affair, although he himself was innocent. Since the supernatural power of Resi Prakampa was maltreated, Mt. Kapi [Krakatau] exploded, accompanied by the disasters of flooding water, heavy rain and typhoon storm. Mt. Kapi collapsed and entered the earth, and the seawater flooded the mainland from Mt. Gede [near Bogor] to Mt. Rajabasa [in Lampung]. After the subsidence, Java Island was divided into two islands, and the western part was named as Sumatra, while the eastern part remained to be called Java. The part of land around Mt. Krakatau sank and became the Sunda Strait, and Samaskuta Country vanished to the earth to become Lake Singkarak in Padang.”

In his book, Catastrophe – An investigation into the Origin of the Modern World [36] , David Keys assumed that various calamities experienced in various places on the Earth after the middle of the 6th century were caused by an extraordinary natural phenomenon and speculated that it was the great explosion of Krakatau that occurred in 535 AD. The same author also referred to a record in History of Southern Dynasties (of Sung) that in December (intercalary) in 529 AD, thunder claps were twice heard from the southwest direction [37], and supposed they were the noises of Krakatau’s eruption, which he assumed to have happened in 535.

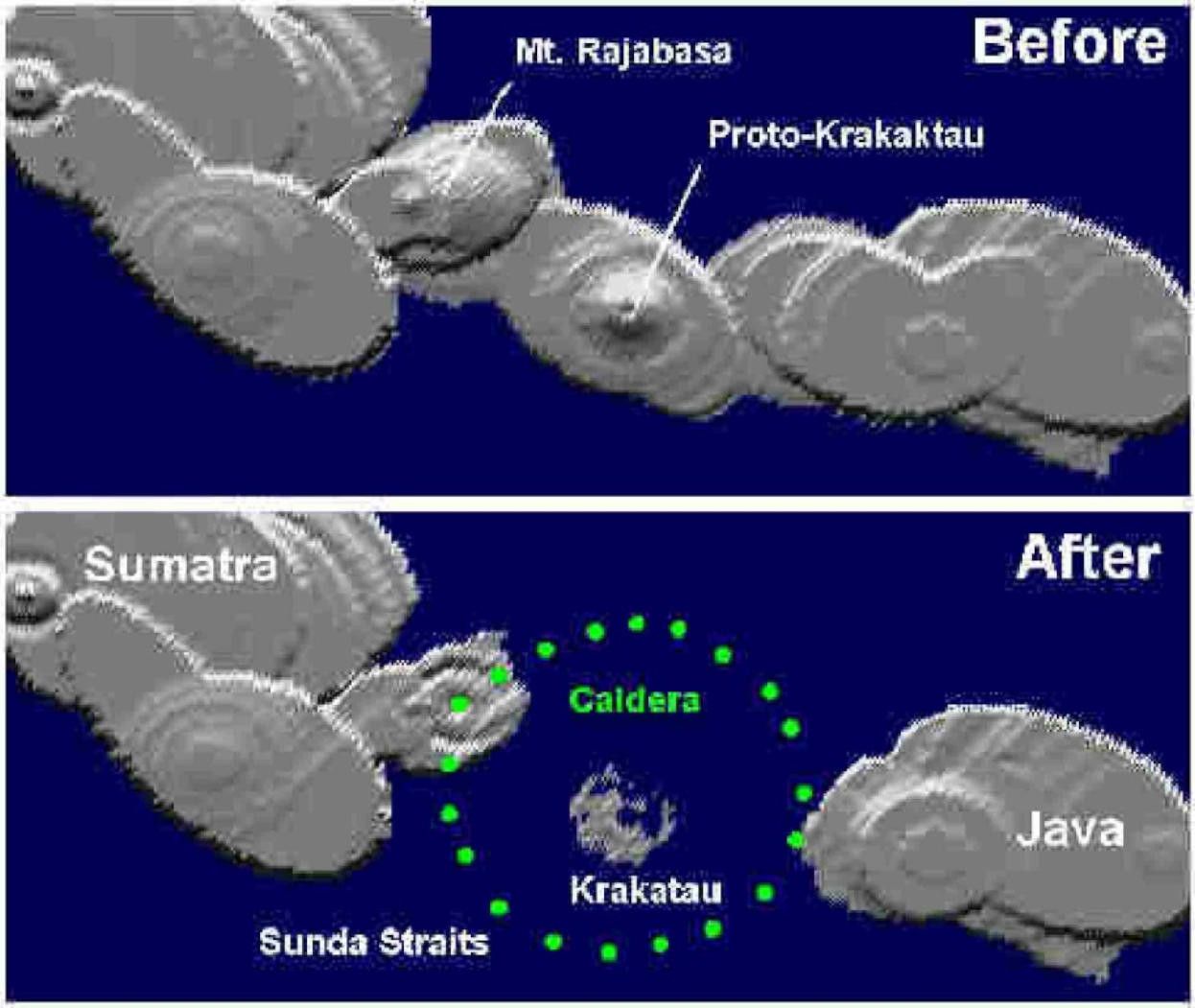

Dr. Wohletz [38] who cooperated with Mr. Keys in raising the hypothesis had carried out a computer simulation, by assuming the amount of emitted magma as 200 cubic kilometres (i.e. several times bigger than that from Mt. Tombora in Samba Island, Flores in 1815, the largest ever recorded in the historical time) and the diameter as 50 kilometres, and by placing Mt. Proto-Krakatau at the crater, and showed a map in which Sumatra and Java Island had been connected by land.

|

Computer simulation to show the break-up of Java and Sumatra Islands by the eruption of Krakatau in an ancient time. Reproduced by courtesy of Dr. K. H. Wohletz, from: |

A question remains as to when the eruption had really happened. As to the difference of 119 years between 535 AD assumed by Mr. Keys and 416 AD in The Book of Ancient Kings, the author wrote that the latter year would have been an error arisen when the book was compiled on an oral tradition or a document of some 1,000 years older that might not have remained, but that possibility would be pretty low as the description in the source book was quite systematic. What the readers should note is that the year as well as the location of Mr. Keys’s assumption was nothing but the result of induction from circumstantial evidence. The simulation by Dr. Wohletz itself was not the kind that was to help the determination of the year. A view that “In early Chinese documents, Java and Sumatra were not well distinguished and, in some period, the two islands were called by one single word. This situation continued until early 400 AD”[39] in the article by Prof. Chihara, an expert of ancient Javanese architecture, could not be direct supporting evidence either.

The year 416 AD was in the heyday of Tarumanagara under the reign of the third king, Purnawarman (395–434 AD) and the prosperity continued in the time of the next king, Wisnuwarman (434–45 AD) when he sent a mission to Sung and established diplomatic relations with China. Although it was not referred by Mr. Keys, a stone inscription called Prasasti Pasir Muara found near Prasasti Kebun Kopi recorded:

|

This is a statement by Rakryan Juru Pengambat in Saka 458 [536 AD] that the country’s government returned to the King of Sunda |

in which Rakryan Juru Pengambat is considered as an official [40]. The year 536 AD was around the time when the throne of Tarumanagara was succeeded from the 6th king Chandrawarman (515–35) to the 7th Suryawarman (535–61), and when Manikmaya, the son-in-law of Suryawarman had founded a new kingdom in Kendan to the east of the present-day Bandung (reigned 516–68 AD). It suggests that there was some calamity that obliged the move of the government seat, although who the King of Sunda was and where the capital was, is completely unknown; it does not necessarily hint whether the eruption was such a huge one to split the island into Java and Sumatra.

Pulau Api (Api Island) in the above-mentioned The book of kings in the land of archipelago is supposed to be an island where Mt. Api (Mt. Kapi or Mt. Krakatau) existed. From the fact that “West Java, Pulau Api and the southern part of Somateria Island” were coordinated, these islands are regarded to have already been separated and independent from each other, at least in the 2nd century. As far as I have checked, in the same book, no description that suggested a volcanic eruption was found.

From studies of sedimentary deposits around the Strait of Sunda, an estimation that the ancient Krakatau had occurred about 60,000 years ago has been published, but it does not seem to be sure among geologists [41].

The explosion of Krakatau in 1883

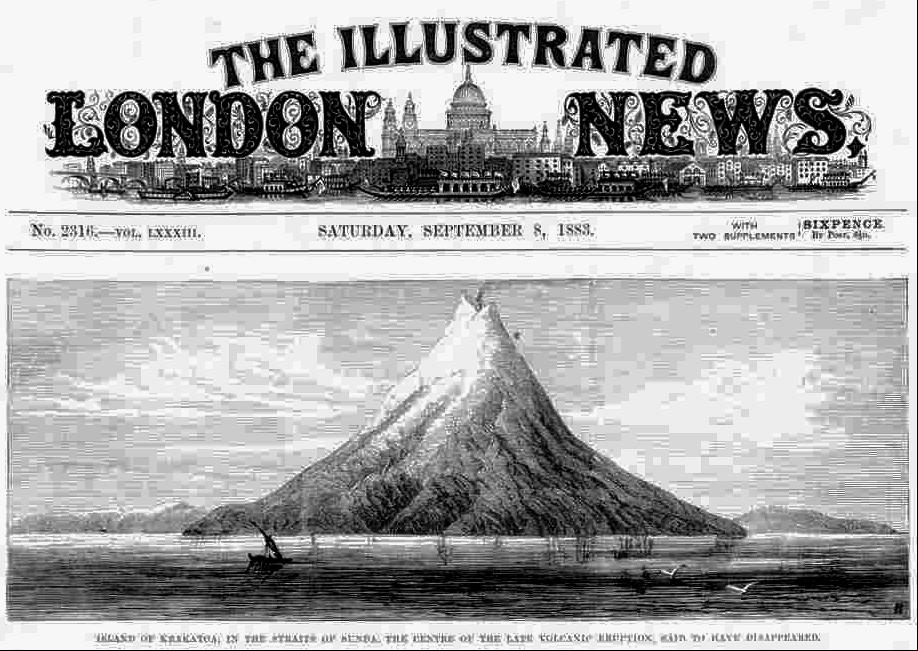

The explosion of Krakatau in 1883 itself was also a world-shaking event of nature in which an island with a main peak of 813 metres high was blown off; the noise was heard 3,500 km away in Perth, Western Australia, and the island of Rodrigues in the Indian Ocean, 4,800 km away. The huge tsunami drowned the towns and villages in coastal areas of Java and Sumatra to claim tens of thousands of lives, the official toll being 36,417 persons.

|

A sketch of Krakatau before the eruption in 1883. (The Illustrated London News, 8 September 1886). Reproduced from: http://alltomvetenskap.se/index.aspx?article=4474 |

In the heyday of cinerama, there was a film, entitled Krakatoa –East of java [42], the story of which was related to this calamity. Having reviewed it on DVD, I was quite impressed again by the realistic scenes of emitting fire and flowing lava filmed, long before the emergence of digital technologies, in this Academy Award nominee film for Best Visual Effects.

At the eruption of Krakatau in 1883, in response to the call of reports by the scientific journal, Nature, a Victorian poet, Gerald Manley Hopkins (1844–89) described the colour of the sunset, which he saw on the evening of 19th October 1884 in Dublin, in one of his letters to the editor as follows [43]:

|

It was intense: bronzy near the earth; above like peach, or of the blush colour on ripe hazels. It drew away southwards. It would seem as if the volcanic “wrack” had become a satellite to the Earth, like Saturn’s rings and was subject to phases, of which we are now witnessing a vivid one. |

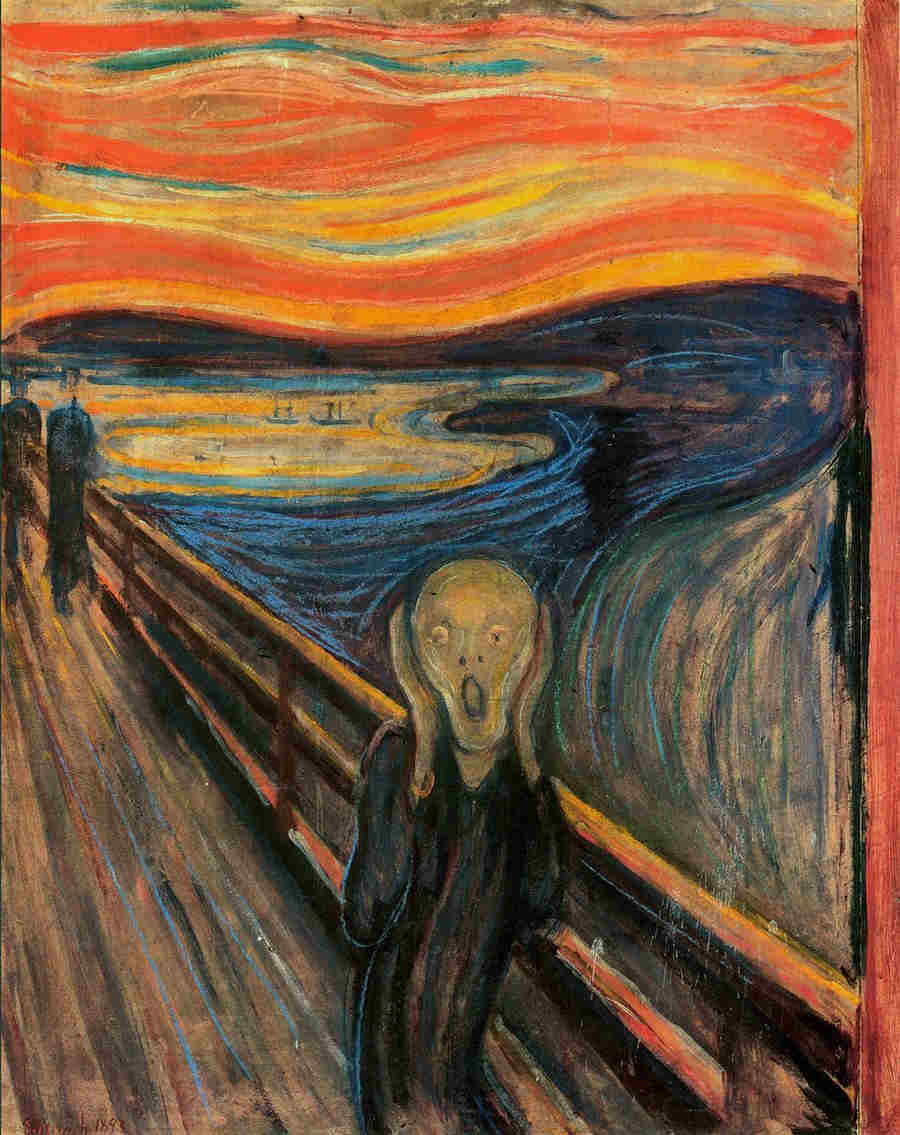

Indeed, a poet and academic who had a position in a university (Dublin), Hopkins was able to describe the scene of the sunset by words which Norwegian artist Edvar Munch expressed later by colour in The Scream (1893).

|

The Scream by Edvard Munch 1893. Reproduced from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Scream.jpg |

In a number of books and articles, a poem below was quoted as a work of Lord Alfred Tennyson:

|

Had the fierce ashes of some fiery peak Been hurled so high they ranged about the globe? For day by day, thro’ many a blood-red eve, The wrathful sunset glared. |

It sounded “Krakatau-like”, but it had long been my question whether this quatrain was really a complete work of the Victorian poet laureate who usually wrote long poems. In 2003, the answer was received from Prof. Jeff Matthews [44] who kindly tackled the problem in that it was actually an unauthorised extract, by an unknown person, from an 80-line poem, "St. Telemachus" [45], in which the poet had imagined that the atmospheric conditions had been similar in 400 AD when the monk (also known as Almachius) heard God’s voice in Asia (the present-day Asia Minor or Anatoria) and went to Rome to stop the bloody gladiatory game. (After St. Telemachus was martyred to death by the stones cast by the mob, Emperor Honorius prohibited the gladiatory game from being performed in Rome forever.) Krakatau Island, which had vanished by the explosion of 1883, appeared again above the sea-surface in 1927 and grew to Anak Krakatau (lit. Child of Krakatau), the peak of which being as high as 300 metres in 2005. The little mountain slowly blowing out a strand of smoke can be seen from Anyer in the west coast of Java.

|

St Telemaachus. Reproduced from: Ade Bethune, Eye Contact With God Through Pictures: A Clip Book of Pictures from the Ade Bethune Collection , Sheed & Ward, Kansas 1986. |

Let me add several lines about the name of Krakatau, which is alternatively called Krakatoa, namely in English. It is alleged to have come from the misspelling of the Portuguese, “Krakataõ”, made by a British journalist at the time of the 1883 eruption. Probably, this is a very rare case that a wrong spelling has been adopted for a long time, up until today. While the name, Krakatau itself is widely said to have derived from a Sanskrit word, “karkata” for “crab”, it was written in a recent book that “krakara” for “saw” in Sanskrit was the origin [46]. From the similarity of the spelling and the notched shape of the mountain, which existed before the 1883 eruption, the latter assumption might be more plausible.

Before ending this chapter, let us review the royal lines of major kingdoms that existed in the past in West Java, which are known from The Book of Kings in the Archipelago and other sources. The lineage of Tarumanagara, which commenced by Jayasinghawarman in 358, was maintained for more than twelve centuries until the end of Pajajaran in 1579, during which fifty-two kings reigned. If we count it from the founding of Salakanagara in 130 AD by Dewawarman the First, the period spanned over fourteen centuries and the number of kings was sixty-four ( See the detail in Appendix 3.2).

| Salakanagara Kingdom | 130–358 | 12 kings |

| Tarumanagara Kingdom | 358–669 |

12 kings |

| Kendan/Galuh Kingdom | 516–852 | 14 kings |

| Sunda Kingdom | 669–1333 | 28 kings |

| Kawali Kingdom | 1333–1482 | 6 kings |

| Pajajaran Kingdom | 1482–1579 | 6 kings |

[1] Ciaruteun, literally Aruteun River. Ci- is a prefix in Sundanese meaning “water”, or river, lake, swamp, marsh, etc. In West Java there are a number of places with this suffix.

[2] J. Ph. Vogel, The Earliest Sanskrit Inscriptions of Java (in: F. D. K. Bosch, (Ed.) Publicaties van den Oudheidkundigen Dienst in Nederlandsch- Indie, Deel 1 , Albrecht & Co., Batavia 1925).

[3] Stutterheim wrote in 1925 that it was not yet deciphered (W. F. Stutterheim, (Trans. by Mrs. A. C. de Winter-Keen), Pictorial history of civilization in Java, The Java Institute and G. Kolff & Co., Weltevreden, 1927), but the translation into a modern language was shown in a treatise by Vogel (Footnote 2) in the same year, 1925.

[4] Abdurachman Surjomiharjo, Pemekaran Kota Jakarta/The Growth of Jakarta, Penerbit Djambatan, Jakarta 1977.

[5] The first statue was discovered in 1959 (1957?) by a Frenchman, Jean Boisselier, and judged in the next year as a curving of the 7th century by Prof. Edi Sedyawati, University of Indonesia. The second statue was unearthed in 1975. (The Jakarta Post, “Sites tell of prehistoric societies”, The Jakarta Post (27 February 2007), http://www.southeastasianarchaeology.com/2007/02/27/sites-tell-of-prehistoric-societies-indonesia/).

[6] Based on the decipherment in Footnote 2, but some unclear part has been filled by the present writer with reference to: Saleh Danasasmita, Sejarah Bogor, Pemerintah Daerah Kotamadya DT II Bogor, 1983.

[7] Phalguna and Caitra of the Hindu calendar correspond to 20 February–21 March, and 22 March–20 April, respectively. See Appendix 3.1. Since each month is divided into white-half (new moon to full moon) and dark-half (from full moon to new moon), the period in the text is calculated to be twenty-one days.

[8] F. D. K. Bosch, Selected Studies in Indonesian Archaeology, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague 1961.

[9] Akira Goto, A history of Islamic world, University of Air 1993 (後藤明, 「イスラーム世界の歴史」, 放送大学教育振興会 1993).

[10] Chinese text, 永建六年, 日南徼外葉調王便, 遣使貢獻, 帝賜調便, 金印紫綬. http://toyoshi.lit.nagoya .ac.jp/maruha/kanseki/houhan076.html.

[11] The interpretation that Ya-diao (葉調) corresponded to Dewawarman was given by Paul Pelliot (1916) and G. Ferrand (1919) (G. Coedes, Indianized States of Southeast Asia, University of Hawaii Press 1968). Whilst G. Ferrand regarded “便” as Warman and “調便” as Dewawarman (Translator’s note in [W. Fruin-Mees, Geschiedenis van Java, Vol 1: Het Hindoetijdperk. Vol 2: De Mohammedaansche rijken tot de bevestiging van de macht der compagnie , Commissie voor de Volkslectuur, Weltevreden 1919 & 1920 /Japanese translation by Matsuoka: Madame Fruin-Mees, History of Java, Iwanami Publishing 1924 (フロイン・メース夫人著・松岡 静雄訳「爪哇史」岩波書店 1924)].Kurihara assumed that “調” in “調便” was an extraneous character (Tomonobu Kurihara, Study on the history of Qin and Han, Yoshikawa-koubunkan 1986 (栗原朋信 「秦漢史の研究」吉川弘文館 1986 ). A theory that “葉調王便” was Purnawarman in Daigoro Chihara, The architecture of Borobudur, Hara-Shobo 1970 (千原大五郎「ボロブドールの建築」, 原書房 1970) is obviously wrong as the time difference is as much as 250 years.

[12] Chinese text, 乃至一國名耶婆提其國外道婆羅門興盛佛法不足言, Classic Book Publisher, The life of Faxian, Xinfua-bookstore 1955 (文學古籍刊行社出版「法顯傳」, 新華書店, 上海 1955).

[13] Chinese text, 「呵羅單國治闍婆洲。元嘉七年,遣使獻金剛指鐶,赤鸚鵡鳥,天竺國白疊古貝,葉波國古貝等物。十年,呵羅單國王毗沙跋摩奉表曰: 常勝天子陛下:諸佛世尊,常樂安隱,三達六通,. . .」。 (Nagoya University, Sung Shu [The Book of Sung] Vol. 97, Legends 57, Foreign Countries: Arotan Country (宋書卷九十七・列傳第五十七・夷蠻: 呵羅單國), http://toyoshi.lit.nagoya-u.ac.jp/maruha/kanseki/songshu097.html.

[14] In K. Iwamoto, “Sailendra Dynasty and Borobudur”, [In: Southeast Asia – History and Culture, Society of South East Asia History, Heibonsha, Tokyo] 1981 (岩本薫, “Sailendra王朝とCandi Borobudur”, 東南アジア史学会「東南アジア‐歴史と文化」, 平凡社), Iwamoto wrote that “The author considers that '呵羅單國' was the phonetic transcription of Sailendra”, showing neither any phonetic interpretation nor any historical evidence. This is obviously wrong, primarily because there was a 3.5-century time difference between the heyday of Tarumanagara (ca. 400 AD) and the rise of Sailendra (mid-8th century). In the latter kingdom, there was no name of a king that sounded like Wisnuwarman.

[15] Slamet Mulyana, Dari Holotan ke Jayakarta, Yayasan Idayu, Jakarta 1980.

[16] Parrots belong to the so-called Australian species distributed to the east of the Wallace-line, which passes between Bali and Lombok Islands, and between Borneo and Celebes.

[17] Chinese text, 單單在振州東南多羅磨之西. 唐書卷二百二十二下・列傳第一百四十七下・南蠻下 (Tang Shu [The Book of Tang] Vol. 222-1/2, Legends 147, Foreign Countries 2, “Taruma...” ), http://toyoshi.lit.nagoya-u.ac.jp/maruha/kanseki/xintangshu222c.html.

[18] Naskah Wangsakerta, also called Naskah Cirebon, compiled by Panitia Pangeran Wangsakerta (Prince Wangsakerta Committee). They include such books as Pustaka rajya rajya i bhumi Nusantara (The book of kings in the archipelago),Pustaka Pararatwan i bhumi Jawadwipa ( The Book of Jawadwipa) and others, altogether some thirty books.

[19] Saleh Danasasmita, Sejarah Bogor, Pemerintah Daerah Kotamadya DT II Bogor, 1983, and some other literature.

[20] Poerbatjaraka, Riwajat Indonesia, Dijilid I, Djakarta 1952, cited in, A. Surjomihardjo, Pemekaran Kota Jakarta/The Growth of Jakarta, Penerbit Djambatan 1977.

[21] http://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kerajaan_Salakanagara.

[22] 1453 AD, the fall of Constantinople.

[23] First Class: Brahman=Priesthood, Second Class: Kshatriya=Aristocracy and warriors, Third Class: Vaisya=Farmers, artisans and merchants, Fourth Class: Sudra=Labourers and slaves.

[24] A. J. Eijkman, F. W. Stapel, Leerboek der geshiedenis van Nederlandsch-Indie 9th Edition, Gronongen-Batavia 1939 (エイクマン, スタぺル (村上直次郎, 原徹郎訳)「蘭領印度史」, 東亜研究所 1942).

[25] Here, “Java” means Central and East Java where Javanese people live, and the “remains” denote such monuments at Dieng, Borobudur, Prambanan, Singasari, etc.

[26] Atja, (Ed.) S. Ekadjati, Pustaka rajya rajya i bhumi Nusantara, suntingan naskah dan terjemahan I 1 , Bagian Proyek Penelitian dan Pengkajian Kebudayaan Sunda (Sundanologi), Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 1987.

[27] J. G. de Casparis, Indonesian palaeography, E. J. Brill, Leiden/Koeln 1975.

[28] Adolf Heuken SJ, Historical Sites of Jakarta, 6th Ed., Cipta Loka Caraca Foundation, Jakarta 2000.

[29] The average from 1916 to 1919/ Norris McWhirter, Ross McWhirter, The Guinness Book of Records, Guinness Superlatives Ltd, London, October 1970.

[30] This paragraph and the bird’s eye view of West Java have been added in this English edition (Not included in the Japanese edition published earlier in October 2013).

[31] This paragraph is new in this English edition, not in the Japanese edition published earlier in October 2013. In Indonesia, snow falls only on Puncak Jaya (4, 884 m), the highest peak in Papua (formerly called Irian Jaja or West New Guinea) or the Pacific Basin.

[32] Paper arrived in Japan relatively earlier in the 6th–7th centuries, whilst it was transferred to the Islamic world and Europe in the 14th and the 15th centuries, respectively. To Java, paper must have been brought by the Portuguese in the 15th century at the latest, but it was not until the 19th century that it became widely used.

[33] J. W. Judd, “The earlier eruptions of Krakatau”, Nature 40, 1889, 365. Pustaka Raja Purwa (Book of ancient kings) written in the 1860–80s by a Solonese court poet, Ranggawarsita III, is said to be the longest book in the world. The book held in the court library in Surakarta (Solo) is not open to the public.

[34] Purwadi, Sejarah asal-usul tanah Jawa, Persada, 2004 [In, Hamamdin, Aceh Hingga Bali Membentang Dalam Satu Pulau, May 11, 2009] (http://poestaka-ku.blogspot.jp/2009/05/aceh-hingga-bali-membentang-dalam-satu.html).

[35] The age of Aji Saka was six hundred years earlier than the emergence of Islam in the 7th century. Although the word “sultan” primarily meant the sovereign or chief ruler of an Islamic country, this word became used for a dictator or tyrant in general, e.g. “Sultan Cromwell” in English (OED2). Thus, the using of this word in the Serat Mahaparwa in the 10th century was not inadequate.

[36] David Keys, Catastrophe – An investigation into the Origin of the Modern World, Century, London.

[37] Probably, the original author refered to a record in History of Southern Dynasties Vol. 7 – Liang Book Middle Chapt. 7 (南史總目卷七, 梁本紀中第七, “大通元年 (西暦529)閏十二月丙午, 西南有雷聲二”). The present writer has also found a record in the Liang Book 2 – Main 2 that “In the era of Emperor Wudi in November 505 AD, the weather was fine, lightnings were seen in the southwest direction and thunder claps were heard three times: in Intercalary December in 505 AD thunder claps were heard twice in the southwest direction (武帝中, 天監四年 (西暦505年)十一月甲午, 天晴朗, 西南有電光, 聞如雷聲三;天監五年 (西暦506年)閏十二月丙午, 西南有雷聲二).

[38] K. H. Wohletz, “Were the Dark Ages triggered by volcano-related climate changes in the 6th century?”, EOS Trans Amer Geophys Union 2000, 48 (81), F1305 (http://deephaven.ca/were-the-dark-ages-triggered-by-volcano-related-climate-changes-in-the-6th-century/).

[39] 佐和隆研編「インドネシアの遺跡と美術」, 日本放送出版協会 1973 (Ryuken Sawa (Ed.), Historical remains and art in Indonesia, NHK Publishing 1973).

[41] E.g. Ian W. B. Thornton, Krakatau: The destruction and reassembly of an island ecosystem , Harvard University Press, 1997; Simon Winchester, Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded: August 27, 1883, Harper Perennial, 2005.

[42] Directed by Bernard L. Kowalski, starring Maximilian Schell, Diane Baker et al., Distributed by Cinerama Releasing Corporation, 1969. The location of the volcano was changed on purpose from the west to the east of Java Island.

[43] Nature, 30 Oct. 1884, page 663. Also in; Norman White, Hopkins: A literary biography, Oxford University Press, 1995.

[44] Jeff Mathews, “Tennyson, Vesuvius & St. Telemachus”

http://www.naplesldm.com/tenn.html

[45] Alfred Lord Tennyson, The Works of Alfred Lord Tennyson Poet Laureate, Macmillan and Co., London 1894, p.840–1.

|

The first eleven lines of St. Telemachus are as follows: Had the fierce ashes of some fiery peak Been hurl’d so high they ranged about the globe? For day by day, thro' many a blood-red eve, In that four-hundredth summer after Christ, The wrathful sunset glared against a cross Rear’d on the tumbled ruins of an old fane No longer sacred to the Sun, and flamed On one huge slope beyond, where in his cave The man, whose pious hand had built the cross, A man who never changed a word with men, Fasted and pray’d, Telemachus the Saint. |

[46] Arysio Santos, The Lost Continent Finally Found, North Atlantic Books 2011. An example of mountain named after the resemblance of the shape with the tooth of saw also exists in Japan, i.e., Nokogiri-dake (Lit. Mt. Saw, 2,685 m) in the Akaishi Mountain Range.