Jagatara Tales

The history museum, Jakarta History Museum in the Old Batavia area (the present-day Kota), holds many collections that are quite interesting if one enquires about their origins, in addition to the portrait of Jan Pieterszoon Coen mentioned in the previous chapter.

If one goes straight from the central entrance to the back courtyard of the building, an antique cannon, as big as 15 cm caliber and four metres long, named "Si Jagur" appears in front of you. I remember that until several years ago the cannon was located on the pavement beyond the front square of the museum (now called Taman Fatahillah), but, according to old books[1] ,[2], it had once been positioned on the grass on the outside of the city wall. On the rear side of the barrel is attached an enormous fist, which must have been cast together with the barrel itself. Marquis Tokugawa, who saw it in 1921, wrote in his famous travelogue, Journeys to Java[2a], "Although it is a kind of item that, if in Japan, would be placed in a special room and hidden from public eyes, the Dutch do not mind and leave it there exposed to anyone. Then, people are not surprised." Indeed, the clenched fist with its thumb protruding between the pointing and the middle fingers looks strange even for us in these more modern times.

|

Si Jagur (alias: Kyai Setomo). The statue of Hermes is seen at the sight of the cannon. Jakarta History Museum. Photograph taken by M. Iguchi, 2007. |

|

Ki Amuk in the front yard of Banten Museum. Photographed by M. Iguchi, March 1998. |

According to the same book, there was a belief that Si Jagur was a man, alternatively called Kyai Setomo, and that "when he was to marry his fiancée cannon in Bantam [the present Banten Lama], Java would become independent by beating and expelling foreign powers", although in reality they were to be kept separated until today, even sixty-five years after the independence of Indonesia. In the front courtyard of the Museum of Banten Lama, I saw a cannon named Ki Amuk (or Ki Pamuk), which would match Kyai Setomo in both size and shape but with no fist attached, and it was said inThe Sultanate of Banten [3] that Ki Amuk was male and the other one in Jakarta was female, contrary to the description in Journeys to Java. In any case, according to the tradition written in a manuscript by Ranggawarsita, a famous 19th-century court poet in Solo, and cited elsewhere, Kyai Setomo with a man’s title was no other than a male and his partner was Nyai Setomi who lived in Solo. The story is roughly as follows [4]:

| "Once upon a time, the king of Pajajaran saw, in his dream, a

powerful weapon which sounded like thunder, and ordered his Patih [prime

minister] to look for it at the risk of his life. In great difficulty,

the Patih went into deep prayer with his wife, Nyai Setomi, to ask god’s

help, and did not show himself to the court. Receiving a report from a

messenger that two strange things were discovered in the Patih’s house,

the king rushed there and recognised that they were the very weapons he

saw in his dream. Then, a voice was heard that they were the

incarnations of Kyai Setomo and Nyai Setomi. "Later, Sultan Agung of Mataram who (made an expedition to Batavia in 1628-29 and) heard about the weapons ordered them to be brought to the royal capital, Kartasura. Kyai Setomo did not like to stay there and one night he went back to Jakarta by himself. When he arrived in front of the gate of Jakarta Castle, it was already morning and he could not go further. The local people regarded him as a holy cannon, called him Kyai Jagur, and offered little paper umbrellas; Nyai Setomi, who was left in Mataram and moved to the new capital, Surakarta [Solo], was not happy there and wept often. The tears she shed were received in a bowl." |

As an heirloom of the Solonese Royal Family, Nyai Setomi was held in a large coffer placed in the open hall of one of the palaces, Keraton Kasunanan Surakarta Hadiningrat, without being exposed to the eyes of the public. In a photograph found on the internet [5], a small bowl to receive the tears shed by Nyai Setomi was placed on the floor underneath the muzzle, although the size of the cannon itself looked rather small to match her lover cannon in Jakarta. In another photograph in a newspaper [6] taken in 2010 through a semi-transparent curtain on the occasion of the annual cleaning ritual, the diameter of the barrel was apparently comparable with that of Kyai Setomo, being as large as a human head.

|

Nyai Setomi, photographed on the occasion of annual cleaning ritual. KOMPAS Citizen Image 24 Feb 2010. http://citizenimages.kompas.com/citizen/view/52937 Jamasan Maulid. |

|

Guntur Geni, placed in the front square of the Kraton Surakarta Hadiningrat. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012. |

As mentioned in the previous chapter, Nyai Setomi and Ki Amuk along with another cannon, named Guntur Geni, also appeared in the Book of Sakhender as the payment to the Prince of Jayakarta by Baron Sukmul when he came from Spain and acquired Princess Tanuraga of Pajajaran royal lineage, although the destination of Nyai Setomi in that story was not Mataram but Cirebon.

Guntur Geni is also mentioned in the same book. The cannon located in the square in front of the Kraton Surakarta Hadiningrat is a huge one with a barrel of 5.3 m length and 36 cm diameter. Since its nickname, Pancaura, is interpreted to mean 1547, the cannon must have been related to the special event in 1547 Saka or 1625 AD when Sultan Agung was conferred the imperial title of Susuhunan. Although this cannon presumably cast in Mataram was not well made and had some cracks and defects, the detonating sound must have been enormous, giving the name, Guntu

Let us depart from the world of fiction. In reality, Kyai Setomo is believed to have been a trophy that the Dutch obtained during their attack at Portuguese Malacca in 1641 [7]. Also, some other antique cannons existing in Java have their own histories. According to a book by Dr. de Graaf [8], Nyai Setomi was an item that was probably presented to the Prince of Surabaya from the Portuguese around 1609 and was subsequently carried inland by the Mataramese when the latter seized Surabaya. Although the cannon was once plundered from the court (in Karta) in 1677 during the rebellion of the Bugis, it was regained in the next year when the Mataram–Dutch allied force recovered the old capital. Then, it was installed in Kartasura, the new capital of Mataram. It has been held in Surakarta (Solo) ever since 1746 when the royal capital was finally moved there. It is supposed that the name Nyai Setomi was derived from St. Tome, a town in Portuguese Goa (1510–1961), where it was cast, and the name, Kyai Setomo, from Sancta Mariam, the name of the ship that transported the cannon [9]. Probably, the Indonesian word, "meriam", for cannon originated from the same word.

Guntur Geni is also mentioned in the same book. The cannon located in the square in front of the Kraton Surakarta Hadiningrat is a huge one with a barrel of 5.3 m length and 36 cm diameter. Since its nickname, Pancaura, is interpreted to mean 1547, the cannon must have been related to the special event in 1547 Saka or 1625 AD when Sultan Agung was conferred the imperial title of Susuhunan. Although this cannon presumably cast in Mataram was not well made and had some cracks and defects, the detonating sound must have been enormous, giving the name, Guntur Geni (lit. Fiery Thunder)[10].

Back to Jakarta, there was a saying among local people that an infertile woman would be blessed with a child if she visited Si Jagur, as the name means "Mr. Robust" or "Mr. Fertility". In fact, I remember that flowers were offered and incense burnt around the cannon when it was still located outside the museum. On the rear side of the cannon's barrel is wound a bronze belt on which is carved in relief in Latin:

|

EX ME IPSA RENATA SUM [I was born from myself] |

I cannot guess the intent of the gunsmith who carved this phrase and put the strange fist on an object that was a weapon of war. With respect to Nyai Setomi in Solo, such prayers as "Oh Jesus, Thou art the most perfect being who guides people of the world" are said to have been carved, along with the symbol of the Portuguese king [11]. This is understandable as a sincere wish of a gunsmith.

The monument of Pieter Erberveld, a rebel

In the left-hand side (east side) of the museum’s back courtyard, one finds a stone wall on the tablet on which is inscribed in both Dutch and Javanese:

|

In consequence of the detested memory of Pieter Erberveld, who was punished for treason, no one shall be permitted to build in wood, or stone, or to plant anything whatsoever, in these grounds, from this time forth for ever more. Batavia, 14 April 1722 [12] |

This monument for remembering the rebellion of a certain Pieter Erberveld was originally a gate of his house that was walled up by cement. Before the Second World War, the skull of Erberveld, which was pierced by a spear and fixed with gypsum, and placed on top of the gate, was an attraction for sightseers. The summary of the incident was written in many books as, "Pieter Erberveld was born, as the last son of six brothers, to a rich merchant who came from Germany and made his fortune, and a local woman (or a Siamese woman). Unlike his elder brothers who grew up into European-like men, Pieter became a fanatic Javanist. He, together with some comrades, conspired to massacre all Europeans in Batavia, but the plot was uncovered and he was executed." The detail was found in Java: Past and Present, written one hundred years ago by Donald Campbell [13], an English businessman and historian. The description over ten pages is quite interesting, as if it were a script of a play, but let us follow the outline.

When Pieter Erberveld was planning a coup d’etat, he would have thought it difficult for him, a son of a mere merchant, to become the leader of a country. Then, Raden Kartadriya and his brother from the court of Mataram appeared with an ambition to become the king and the sultan, respectively, once the power was taken, the positions that were unexpected for them in normal situation due to their low ranks in the court. Pieter Erberveld himself was probably content if such a position as the Highest Priest in Java was to be assumed.

| The walled-up gate of Pieter Erberveld's house, on which his skull was put up. Jakarta History Museum. Photographed by M. Iguchi 2006. |

Digressing from the subject, a struggle for the succession to the throne was very common in Java ever since ancient times, as one might remember that in the 13th century the assassination of kings was repeated three times in Singasari after the kingdom itself was founded by the overthrowing of the king of Kediri by Ken Amrok, and that in the 16th century when Majapahit became weakened by domestic discords and eventually fell to Islamic power. Even in the New Mataram Kingdom, which was established in the 16th century and was to continue to date, there were three family wars, called the Java Succession Wars, in the early 18th century, and the territory was dived into two parts for the Susuhunan Family in Surakarta (Solo) and the Sultan Family in Yogyakarta in 1755, in accordance with the Treaty of Gianti interceded by the Dutch VOC.

Prince Diponegoro who fought the so-called Java War against the Dutch in 1825–30 was made one of the National Heroes after the independence of Indonesia and his name was borne on many town streets as well as the university of Semarang, but the reason for his rebellion was not only his own belief that he himself was destined to be the leader of Java and the sympathy among aristocrats whose rights of land had been detracted [14]. When his father Sultan Hamengkubuwono III died in 1814, the throne was not passed to him but to his younger half-brother, despite the fact that he was the first son of the sultan, because his mother was a woman of low birth, and he was appointed to be an advisor to the new sultan. This was arranged by the advice of Stamford Raffles who ruled Java during the British Era (1811–15). When the new sultan died young in 1923 he again had no chance, to his disappointment, for the same reason. In the beginning of the war, Diponegoro’s troops, using a guerrilla warfare, were successful in embarrassing the Dutch, but the tide soon turned against him. When he appeared for negotiation, he was captured as he did not abandon the title of sultan, which he himself declared. A descendant of the Sultan’s lineage once whispered to me that Diponegoro was remembered as a troublemaker in the family.

|

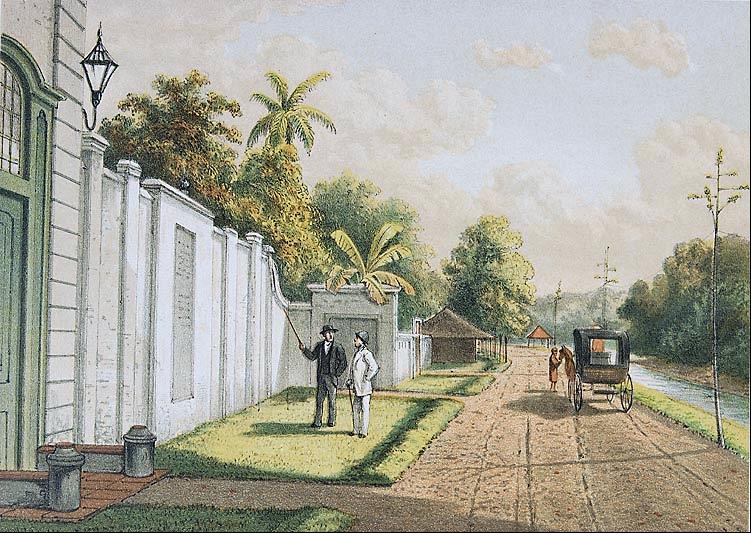

The house of Pieter Erberveld by Josias Cornelis Rappard 1888. Reproduced from: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pieter_Eberveld.JPG The panel to show the legend is seen on the walled-up gate and the skull of Erberveld, on the top. |

Returning to the subject of the conspiracy of Pieter Erberveld, Pieter was unmarried but had a step-daughter, Meeda, a beautiful girl of mixed parentage, adopted from his deceased brother. Despite Pieter’s intention to bring up Meeda like a pure native girl and to let her marry a native boy, Meeda's mind and taste inclined to the European side, and she fell in love with a young Dutch officer, who recognised it by telepathy.

One day, when the Dutch officer resolutely visited Meeda’s uncle to express his wish to marry her, he was sharply told by Pieter that Meeda could not be given to a white man. Although disappointed and exasperated, he found a chance to meet his loved one and proposed a private marriage. Late that same night, she was wondering whether she should betray her uncle and run to her lover. When she was vacantly looking outside from the veranda of her room, she saw some dark bodies pass across the gleam of light filtered through the lower-stair window. Being anxious about her uncle, she went to his room, but he was absent and his bed had no sign of having been pressed that night. Finding her uncle in the corridor, she followed him and saw him enter the dining room in which a number of guests seemed to be gathering. Wondering what was going on, she placed her ear to the keyhole of the door and heard some formidable words whispered between them. Putting her eye to the keyhole, she witnessed a frightful scene in which every man in the room placed his hand on his keris (sword) and, after kissing their hand, repeated the same gesture with the Koran. (This was the same ceremony as Christians swore on the Holy Bible.)

Horrified by what she had heard and seen, Meeda returned to her room and spent the night without sleep. Next morning she secretly wrote and sent a letter to her lover to inform him of the plot, begging if possible to conceal her uncle’s name as one of the conspirators. The young officer was equally horrified, especially by the fact that the meeting was held in the house of his lover’s uncle, but had to divulge the whole details to his senior officer. The government lost no time in sending a warning to the lords in Mataram and other districts in the whole of Java. On the eve of the planned coup, when Pieter Erberveld gave his last message to comrades, "Be ready one hour before the daybreak", his house was already surrounded by the government’s troops.

The fate of Meeda and the young officer, which has long been my question, was described in an old Christian society’s magazine, which recently came into my sight. According to an article, entitled "Pieter Erberveld’s Treason", Meeda and the Dutch officer, Piet van der Volt by name, were married in the old Dutch Reformed Church and the government authorities vied with the Dutch residents in showering honours upon them. It was also written that Pieter Erberveld’s father was a Dutchman named Karl and his mother was a Javanese woman named Boenga Haroem [15].

The sentences given to the principal conspirators, cited in the book by Campbell, were the most formidable ones I have ever read, the decision for Pieter Erberveld and Raden Kartadriya being that "the two shall be bound on a cross on which they have their right hands shall be cut off, and their arms, legs and breast, pinched with red-hot pincers until their flesh are torn away: their bodies ripped from the bottom to top and their hearts thrown away: their head cut off and fixed on the post [as it was seen in later days]". The author wrote, "Such was the punishment of the 18th century", but perhaps not only the Dutch were cruel at that time when, for instance, the burning on the stake and the boiling in a cauldron were said to have been practised in Japan.

With regard to Erberveld’s conspiracy, there is a different theory [16] in that the story was fabricated by the Dutch authority who wanted to expropriate the estate of Erberveld. Even though it was the case of two hundred years ago, it is hardly believable to myself, the theory itself being doubted as a fabrication.

The skull of Pieter Erberveld is supposed to have been demolished from the wall in 1944 during the Japanese occupation [17], but a question remains why the Japanese removed the symbol of a man who had stood against the Dutch. An answer given in Heuken’s book, a historian of Jakarta, was "to please the Indo [18] population of Jakarta", but I would like to think in a different way. Probably the Japanese occupation army was afraid that the local people would see them as overlapping the image of the brutal Dutch in the past.

A replica of Erberveld Monuments with the skull does exist in the Museum Taman Prasasti (Stone-inscription Park Museum), Tanah Abang, Central Jakarta.[18a] According to a caretaker, it was reproduced at the original site after the country’s independence and later moved to the present place. The wall in the History Museum was the genuine one, he added.

I wished to visit the site of the former house of Pieter Erberveld and asked Mrs. E. of the National Museum. She said it must be somewhere around the area called Kampung Pecah Kulit (lit. skin-braking village) and told her husband to accompany me. We went to the area, not far from Kota, where small houses are crowded along narrow streets, but the inhabitants did not know at all about the old traitor and looked indifferent to the loathsome name of their own area, which originated in the bloody execution. We came out to the high street, Jalan Pangeran Jayakarta, and called in to Greja Sion (Sion Church) to ask the location, where a sexton told us it was some two hundred metres down the street. At Jalan Pangeran Jayakarta No. 9–11 was now a modern showroom of Japanese automobiles, bringing no atmosphere of old days where Pieter Erberveld’s house had been replaced with an opium factory and subsequently with a palm oil factory.

The Japanese occupation army also destroyed the statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen in Weltevreden, the Mars and Minerva statues from the alcoves of Amsterdam Gate, the only part of the Batavia Castle that Herman Willem Daendels left untouched when he reformed Batavia, and many other Dutch monuments in the city. In fact, I once read somewhere that the statue of Themis, the Greek Goddess of Justice (equivalent to Roman Justitia), which was once mounted on the Parthenon-style front roof of the building of the Jakarta History Museum, was demolished, probably, in my own guess, by a low-level, uneducated officer who had thought that a Western woman exposing the skin from her shoulder to her arm was inappropriate for the symbol of the building that they had expropriated for their office. In this connection, in Singapore, the statue of Stamford Raffles, the founder of the British possession, was saved by Prof. Tanakadate who rushed there from French Indochina on the outbreak of the war to protect the Museum, in cooperation with Marquis Tokugawa who arrived later as the Supreme Advisor to the army, and returned it to the British after the war [19], [20], [21] . The two intellectuals never permitted the occupation army to touch cultural heritages. Unfortunately, such high-minded persons were not available in the Dutch East Indies. Tomoji Abe and other intelligentsia recruited and sent there for propaganda had no consciousness and discipline to give proper advice to the army. Most of them seem to have been enjoying their lives in the exotic land, some of them having spent most of their time in brothels [22].

Universities, research institutions and museums in Java were fortunately protected, however, by Prof. Tanakadate, who in Singapore worried about their fate. As soon as he flew to Java, he negotiated with the military authority not to touch those facilities and, within a short period, went all around the island to free Dutch academics and researchers from prisons and let them resume their activities. The record of his climbing to Mt. Merapi in Central Java, together with his volcanologist friend, Dr. van Bemmelen, was written inThe Seizure of Southern Cultural Institutions [23]. Another episode remembered is that Prof. T. Nakai from Tokyo Imperial University and Prof. R. Kanehira from Kyushu Imperial University, who served as the director of the Buitenzorg Botanical Garden and the head of the Herbarium, respectively, strove to protect the garden when the Japanese army wanted to cut down and use the trees for lumber [24]. Marquis Tokugawa and Prof. Tanakadate, who both participated as members of the Japanese delegation in the Fourth Pacific Science Congress held at Batavia-Bandung in 1929, must have been "prepared and willing to discuss and solve problems, standing aloof from politics and free from national chauvinism and other more or less egotistical motives", as Dr. de Graeff, the then governor-general of the East-Indies, expected and wished in the opening address of the same congress [25].

The Greja Sion, alias Black Portuguese Church, mentioned above, built in 1615 by the Dutch government for Portuguese–Indian slaves, is another precious historical heritage in Jakarta, having not been renovated for 400 years.

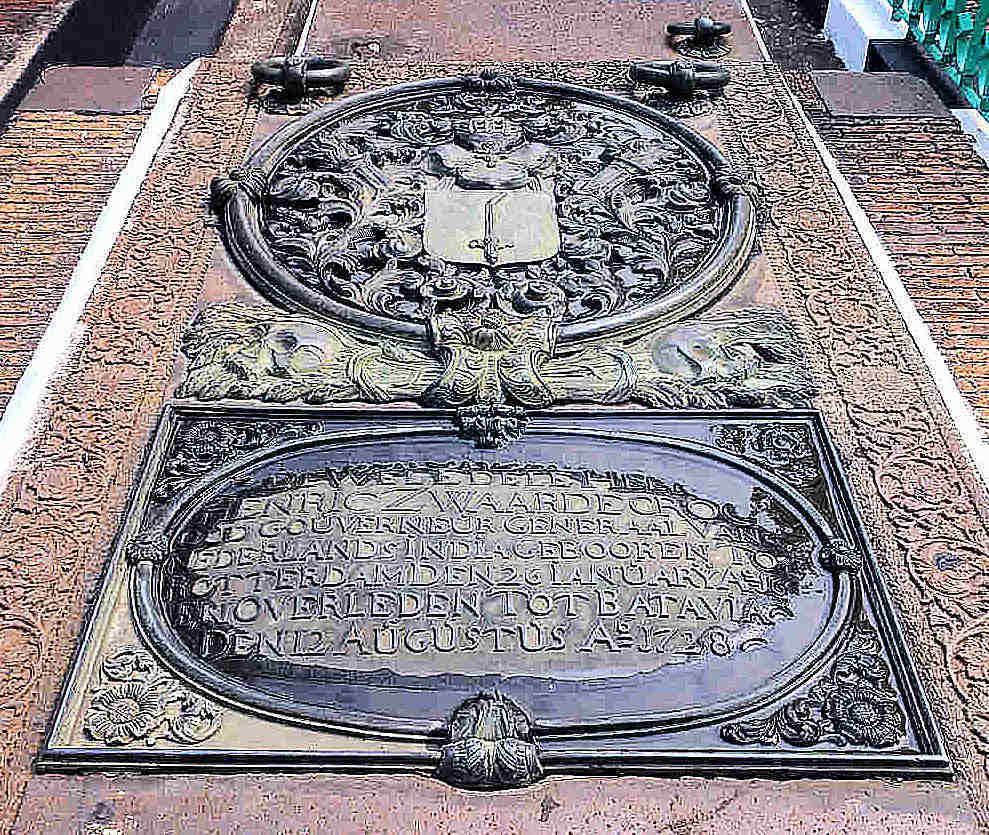

In front of the entrance of this church, on the left-hand side, there was a modest tomb and on the epitaph was inscribed:

| Here rests the honourable Heer Hendric Zwaardecroon, the former Governor-General of Netherland India born in Rotterdam on 26 January A° 1667 and died in Batavia on 12 Augustus A° 1728. |

|

The grave of Governor-General Henric Zwaardecroon in the Greja Sion (Sion Church). Photographed and presented by courtesy of Mr. K. Nishimi.. The epitaph reads, "Hieronder rust de weledele heer Henric Zwaardecroon. oud- Gouverneur-Generaal van Nederlands-India gebooren tot Rotterdam den 26 January A° 1667en overleden tot Batavia den 1 2 Augustus A° 1728". (See, English translation in the text). |

I thought that I was incidentally in front of the tomb of the governor-general who was in office (1718–25) at the time of Pieter Erberveld’s treason, without knowing the facts before, and made a sign of the cross in a Christian manner. Later, I learnt that Zwaardecroon introduced the planting of coffee and the production of silk to Java. Despite him being in such a high position as the governor-general, he preferred to be buried among the poor and lowly people and the silver tankard inlaid with gold was presented by the directors of VOC.

The hall of the church in which we were kindly ushered by the chief priest was a construction of simple Dutch type with no gaudy decoration, although it should have been a church for the Catholic faith. The priest told us that the denomination of the church was converted to Protestantism about a decade ago because of the decrease of Catholic believers in the area.

|

The interior of Greja Sion (Sion Church). Photographed by M. Iguchi 2006.. |

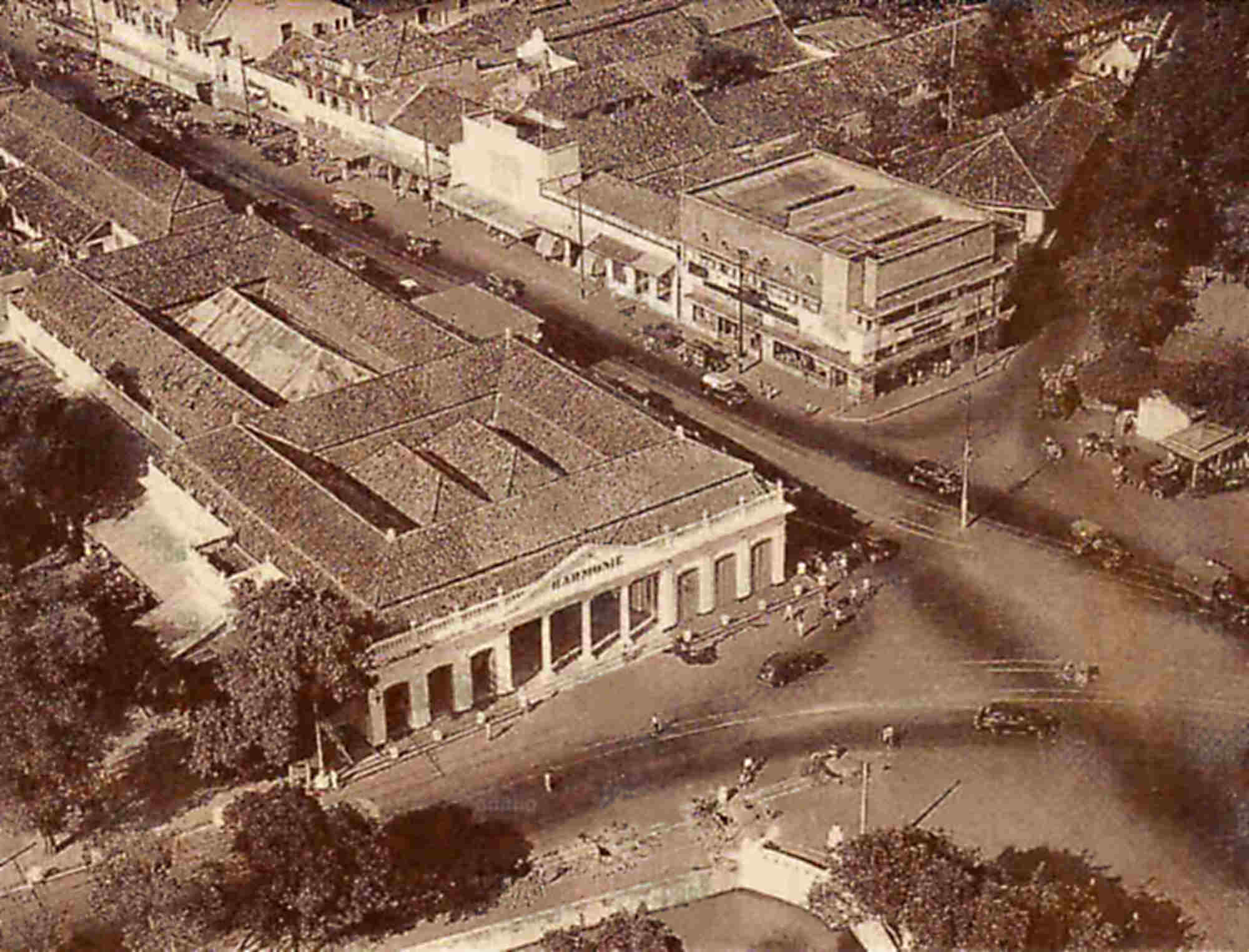

Another object that attracts visitors’ eyes in the back courtyard of the Jakarta Historical Museum is a bronze statue of Hermes, which used to be on the parapet of a bridge at Harmonie, halfway from Kota to the present-day city centre, but I did not see it for some years and was wondering where it had gone. On the tablet of the newly provided stand was inscribed that the statue was moved there in 2000 AD.

|

The Hermes Statue. Jakarta History Museum. Photographed by M. Iguchi 2006. |

Hermes, identical to Roman Mercurius, is, of course, the god of science, commerce, eloquence, and many of the arts of life in Greek mythology, and this statue like many others holds a wand, Kerykeion, the symbol of commerce that was adopted for the school emblem of the Tokyo College of Commerce, the present-day Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo.

In this connection, I should add that at the place in the city that is still called Harmonie stood a famous building named Harmonie, the construction of which was started by Daendels in 1810 and completed in 1815 at the time of Thomas Stamford Raffles. The building was primarily a high-society clubhouse but also a cradle of the present-day National Library and National Museum. It was also remarked as the first modern building constructed by a native contractor. It was awful that the building was demolished in April 1985 by order of the State Secretariat who did not know of its historical value, in order just to widen a road (Jalan Majapahit) and to provide an automobile parking space [26]. In fact, many old buildings were demolished during the time of President Soeharto (1968–98) who had no higher education. For example, the site of the famous Hotel des Indes (pronounced as [ɔtɛl dɛz‿ɛ̃d] in French manner as the founder was a Frenchman) near-by is now a shopping centre.

|

The photograph reproduced by courtesy of Mr. K. Nishimi from

|

In the semi-basement at the rear side of the History Museum building, there are several iron-barred cells in which one can see a number of iron balls of 15–25 cm diameter to which iron chains are attached. The cells were prisons when the building was the City Hall, and once Prince Diponegoro was said to have been detained in one of them until he was deported to Macassar. Needless to say, those iron balls were fetters.

On the ground floor of the museum, on the right-hand side, there are several rooms in which stone inscriptions of the Tarumanagara period (4th–8th centuries), the stone monument of the Pajajaran–Portugal Treaty (1522) and other historical remains are displayed. Although all of them are replicas, as the originals are held in the National Museum, it is an advantage for us to be able to see all of them together with concise legends. The history of the Tarumanagara and Pajajaran eras will be further mentioned in other chapters.

|

One of the cells on the semi-basement of the old City Hall building (the present-day Jakarta History museum). Photograph taken by M. Iguchi 2006. |

The insurrection of the Chinese

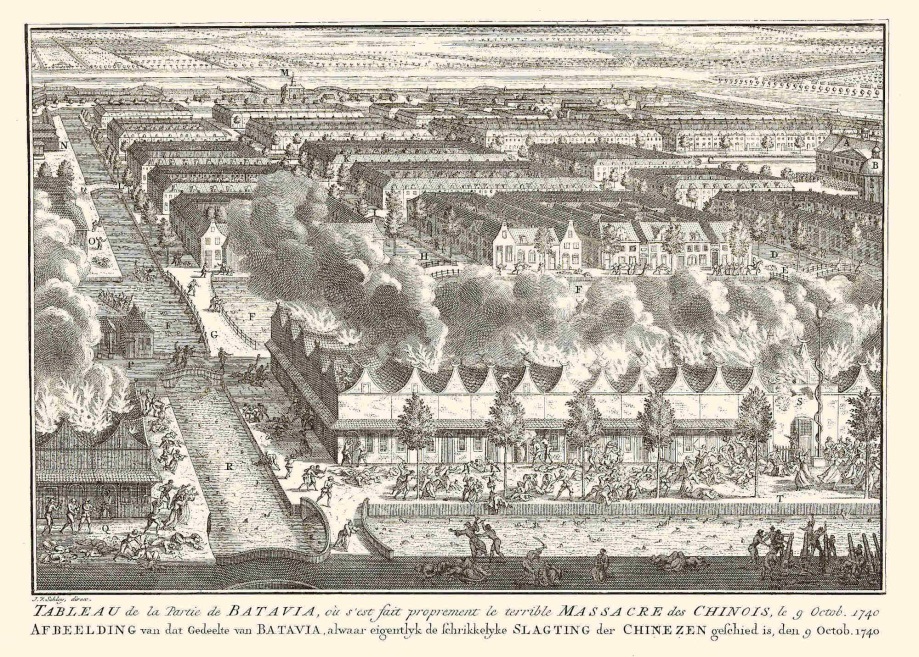

Whilst the rebellion of Pieter Erberveld was prevented before it happened, Batavia saw the bloodiest incident in its history, the insurrection of the Chinese, in October 1740. Although the details are written in many history books, let me cite a lively report that appeared inThe Scots Magazine in July the following year [27].

|

An account of the insurrection of the Chinese at Batavia in October 1740 and a description of that city, as published in Holland, according to letters sent thither from Batavia. |

"I cannot but impart to you the dismal misfortune we have lately met with, viz. a conspiracy amongst the Chinese dwelling in and about this city (who were upwards of 90,000) to massacre every one of us Europeans, and make themselves masters of the island of Java.

"Having with this intent, in bodies of 5 or 6,000 men, for some time infested the highlands, and committed great massacres, rapines, devastations by fire and sword, &c. the cause of which we were not able to learn, the Javans, and those they had forced to assist them, were sometimes taken 30 or 40 together, and 4 or 500 of them examined at once: whereupon 200, who could give no account how they subsisted, were sent to the island of Ceylon, and the rest, that could get their bread, discharged. But this salutary precaution did not avail; the riots increased every day in the highlands, till at last the government judged it expedient to send a detachment thither: for which purpose Mess. Van Imhoff and Van Aarden were sent with 800 men; who, having been some days in the said highlands, gave them battle, routed and dispersed them. In the meantime the Chinese dwelling in and about Batavia had made all manner of preparations, providing themselves with a sufficient number of wooden cannons and other warlike stores, and digging mines underground, which they charged with powder. The treachery being now on the point of execution, it pleased God to discover the whole affair to us, and that too by five Chinese, who of their own accord came and acquainted the government with the scene of blood which their own countrymen were preparing: whereupon all our guards and posts were doubled, and all the Clerks, and even first and second Supercargoes without exception were obliged to mount guard, completely armed, in the castle; tho’ the government did not apprehend the danger to be so great towards proved.

"Matters remaining in this situation for two days, we had intelligence on Saturday the 8th of October, that one of our advanced posts near the island Onrust [28], called Quale, had been surprised by the Chinese, all the Europeans murdered, and everything destroyed by fire: whereupon the government met, and ordered that no Chinese should open his door, appear in the streets, nor burn a light in the night time; and that the contraveeners should immediately be shot to death. Strong guards were also presently posted in all the streets and by-places.

"Whilst the government was yet assembled, in the evening, about 7 o’clock, the Chinese set fire to the suburbs, near the gate of Utrecht, expecting that we would come with all hands to extinguish it; in which case those within would have sallied from their habitations, and so have made an end of us altogether. But they were mistaken, the gates being kept close and well guarded.

"Towards 8, the members of the government took, two by two, the guard of the gates upon themselves, in order to execute in person what commands and orders might be given.

"At 9 o’clock the Chinese, to the number of 40 or 50,000, advanced with a terrible noise of drums, trumpets, basons, and hideous shouts, in order to give their comrades in the city a signal for the attack; but those within seeing our good regulation and order, and that they were deprived of every opportunity to join their brethren, kept themselves very quiet, being seized with fear; and indeed had they ventured upon the matter, in combination with the rest, we had all been destroyed, being little upwards of 3,000 sighting men.

"Meanwhile the Chinese that were before the city continued their havock with fire and sword. They surprised a guard of 15 blacks [29] without the gate of Utrecht, and likewise another without the Dies-gate, all whom they murdered and destroyed. They also fell upon a guard of 60 men near the New gate; but these defended themselves so gallantly that many Chinese were killed, and the gate remained in our hands, it being within reach of our cannon, which ply’d them with good success all that night: moreover, we made a fally with 160 men, both horse and foot, to relieve this post and other Christians inhabiting the out-parts. We could not make a stronger sally, having our sworn enemies both within and without. We spent the night with great courage, tho’ not without danger, finding ourselves in the midst of our foes.

"In the morning the Chinese quitted the suburbs; whereupon the government met, and an order was issued to kill all the Chinese, except the women and children, there being no other remedy to secure us within, and to defend ourselves against the multitudes of enemies without. Accordingly the doors and houses of the Chinese were forced open with axes and engines, and all the men hawled out and massacred; their wives and children were all conveyed to the Chinese hospital. Meanwhile the streets, rivulets and moats, were soon filled with dead bodies, and in some places one might have been over the ankles in blood, so great was the slaughter. In the interim some large guns were planted on the opposite side of the Roemolake [30], to play upon the Chinese Captain's house, where there were upwards of eight hundred Chinese: When we had stormed it, about 30 women came from thence, upon our promising to do them no hurt; however, the Chinese Captain was amongst them, endeavouring to escape in women’s apparel; but, being too well known, he was discovered, and sent to the castle.

"In the afternoon the forementioned Mess. Van Imhoff and Van Aarden returned with their men from the highlands into the city. At the same time, i.e. on Sunday about 2 in the afternoon, the whole city was in flames: for the Chinese, prompted with terror, set fire to their own houses, and perished miserably; and those that came out of doors were instantly slain by our people.

"This great conflagration caused a vast confusion, especially amongst the women, who fled in crowds to the castle, as also those from without, the city being by this time, for the greatest part, and chiefly where the Chinese dwelt, reduced to ashes. There were also 635 Chinese confined in prison, all which were, towards night, put to death pursuant to order.

"During all this confusion, the money and goods of the Chinese were a prey to any body that would enrich themselves by robbery, rapine and murder; and some there are, especially amongst the seafaring men, that have made booties worth 9 to common 10,000 rixdollars. The rest of the Chinese are fled into the mountains, where they continue to destroy every thing with fire and sword; however, our people kill many of them.

"In all this havock we have not lost above 200 men. At present there is a general pardon published for those Chinese that will submit themselves within a month, which several hundreds have already done: however, this pardon does not extend to their two chiefs, but, on the contrary, a reward is promised of 1,000 rixdollars to those that bring them dead, and 5,000 for taking them alive; for the inferior sort, 200 dead, and 300 alive. This pardon expires the 22nd of November, so that all those that have not surrendered by that time are outlawed.

"Such of them as were taken prisoners confess that their plot was to make themselves masters of Batavia, and all the trade there; and that, if they had succeeded, they would have impaled all the members of the regency, cut in pieces and then ate bodies of Imhoff and Tedens, whom they looked upon as enemies of their nation, burnt all persons of an advanced age, slaves of all the youth of both sexes, obliged the General of Batavia, and the Chief Director of the company, to form the meanest domestick offices to the Chief of the Chinese nation and his wife. ’Tis computed that near 12,000 Chinese were massacred."

|

Murder of Chinese in Batavia, 1740 , by Adolf van der Laan. Reproduced from https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/RP-P-OB-75.356 |

In the contemporary picture, it is an amazing fact that roads and canals regularly ran lengthwise and breadthwise and even Chinese houses with curved roofs were orderly arranged. One may say it was the city design, which the Dutch liked, but I cannot but admire their specific character. As far as I know, no scars of the Chinese insurrection remain today.

Let us visit Jakarta Kota Railway Station. The west side of the building with a unique semi-circular facFade and a semi-cylindrical roof is the front, but one may be perplexed as the southern and the northern sides have the same design. The inside of the hall is full of the atmosphere of typical such terminal stations as of Ueno Station in Tokyo or King’s Cross Station in London, and across the barrier are five to six platforms arrayed parallel on the front, some restaurants and souvenir shops on the corner of both sides, touching the heart of travellers. In rush hour, one must be prepared to be jolted in the mass of commuters flowing out of short-range trains from Bogor, Tanjung Priok and other suburbs, as I have actually experienced a couple of times. It was a long time ago during my short visit to Indonesia, prior to my staying in Bogor, that I asked a young station officer about the origin of the station building, as I had a couple of hours to wait for a night train for Central Java. According to a booklet he obtained from his office, the original station opened in 1870 was reformed into the present building in 1926 by a Dutch architect, Frans Johan Louwrens Ghijsels who tried to merge the characteristics of occidental and oriental architecture styles in its design. In those days, the name of the station was Batavia Zuid [31], or Batavia South, as it was located in the southern part of the original ward of Batavia, which constituted Greater Batavia along with Weltevreden, Tanjung Priok and Meester Cornelis. The station was popularly called BEOS, after the abbreviation of Bataviasche Ooster Spoorweg Maatschappij, which had first run a train there. The nickname is still heard today. When I took a taxi in Jakarta and told the driver, "To the station!", and was asked back, "BEOS or Gambir?", the above knowledge helped me to indicate the right destination. Gambir is the name of the station in central Jakarta, the original name of which, Weltevreden, is no longer accepted, unlike BEOS. Although the old name of the city, Batavia, is not heard either, its corrupted form, Butawi, is not completely obsolete, namely among elderly people, as one may hear in provinces, "He went to Butawi.", "Orang Butawi [Jacartans] are cunning.", etc.

|

Jakartakota Station. From the front cover of a Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s book, Tales from Djakarta, reproduced by courtesy of Equinox Publishing (Asia) 2000. |

In Java, the first train ran in 1867 between Semarang and Tangung in Central Java, five years earlier than in Japan between Shimbashi and Yokohama, probably to the surprise of some readers. In fact, the introduction of various modern facilities and systems in the Dutch East Indies was ten to fifteen years earlier and Japan caught them up as late as the 1920s (See Table 1).

|

Table 1 Adoption of modern systems and facilities* |

|

|

Java |

|

Japan |

dif** |

|

1851 |

Modern medical school (Batavia) |

1861 |

(Yedo) |

10 |

|

1858 |

Telecommunication (Batavia–Buitenzorg) |

1869 |

(Tokyo–Yokohama) |

11 |

|

1859 |

Submarine cable (Java islands) |

1872 |

(Shimonoseki–Moji) |

13 |

|

1864 |

Postal stamp |

1871 |

|

7 |

|

1867 |

Railway (Semarang–Tangung) |

1872 |

(Shimbashi–Yokohama) |

5 |

|

1881 |

Telephone (Batavia–Buitenzorg) |

1890 |

(Tokyo–Yokohama) |

9 |

|

1886 |

Modern port (Tanjung Priok) |

1894 |

(Yokohama) |

8 |

|

1925 |

Radio broadcast |

1925 |

|

0 |

|

1928 |

Airline company (KLIM) |

1928 |

(Tozai Airline) |

0 |

|

* Data from H. A. van Coenen Torchiana, Tropical Holland, An Essay on the Birth, Growth and Development of Popular Government in an Oriental Possession , University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1921; Takashi Shiraishi, Brochure for Pramoedya Selection Series 2, Mekon, Tokyo 1968 (白石隆,「プラムディア選集2-付録小冊子」, メコン, 東京 1968). ** Year difference |

||||

The development of infrastructure was far more advanced as Marquis Tokugawa [32] wrote in his travelogue, "The car ran like an arrow on a flat road, the surface of which was as smooth as that of a wheatstone." Those who were equally admired by visiting Java around the same time were not only Yosaburo Takekoshi [33] and Yusuke Tsurumi [34] from Japan, but also an American traveller, Frank Carpenter [35], who said that the quality of roads in Java was comparable with those in Europe and America. I also read somewhere that even a visitor from the Netherlands was envious for the road system in their possession.

In 1940, Ichizo Kobayashi, the founder of Hankyu Railway Company, who visited Batavia as the Minister of Commerce and Industry for the "Economic Negotiations with the Netherlands East Indies" published a book,The Dutch East Indies which I saw [36], which is rarely read today. He wrote about the situation as follows:

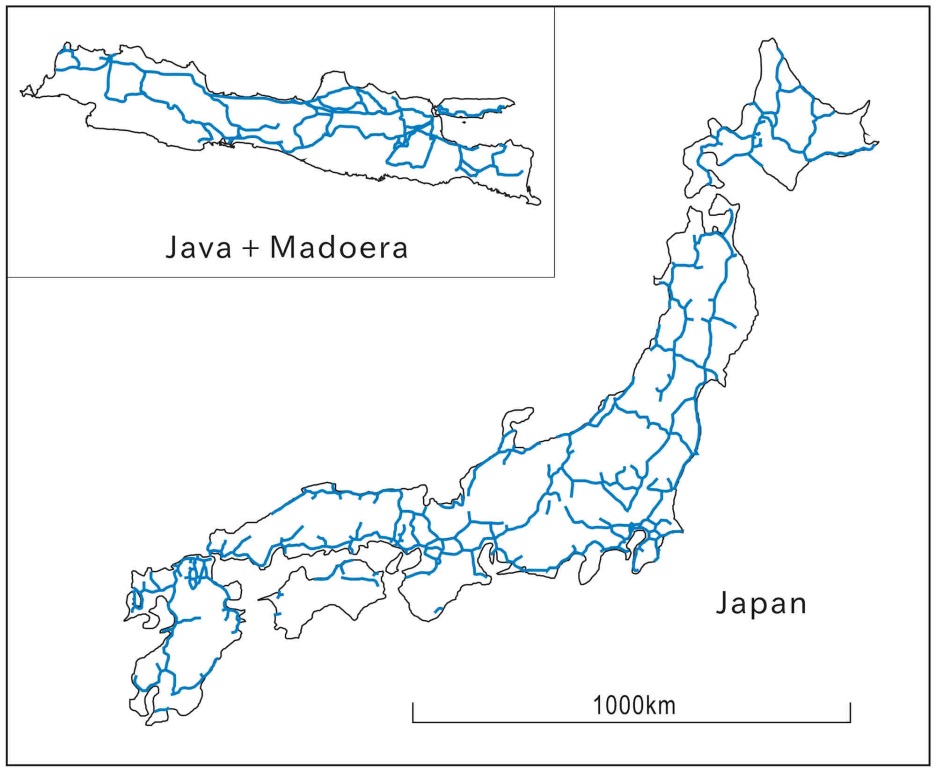

"As far as the Island of Java is concerned, the total length of the railway line is 5,400 km, the length per 100 square kilometre, 5,006, being almost the same as that in Japan, 5,008. The speed of the express train which covers the distance of 830 km from Batavia to Surabaya across the island by twelve hours, as well as the riding comfort and the facilities, is far better than ours on the Tokaido Line. More envious is the road system. The 830 km highway between Batavia and Surabaya, smoothly metallised with asphalt, is quite enjoyable to drive, shaded by banyan, tamarind, and silk trees lined on the both sides. Good works for motorway are complete not only in such a highway. Excellent roads extend from Batavia, Surabaya and Semarang and other cities to all directions up to remote villages and the tops of mountains."

|

Railway systems in Japan and Java-and-Madura in the early 1930s. Java-and-Madura: Redrawn from Kaart en Tekst, eerste Atlas van Nederlandsch-Indie voor de Indishe Lagere School , Groningen-Batavia 1938. Japan: Redrawn from: Railway systems in Japan (1936) http://www.rtri.or.jp/museum-rosen/rosen.html. |

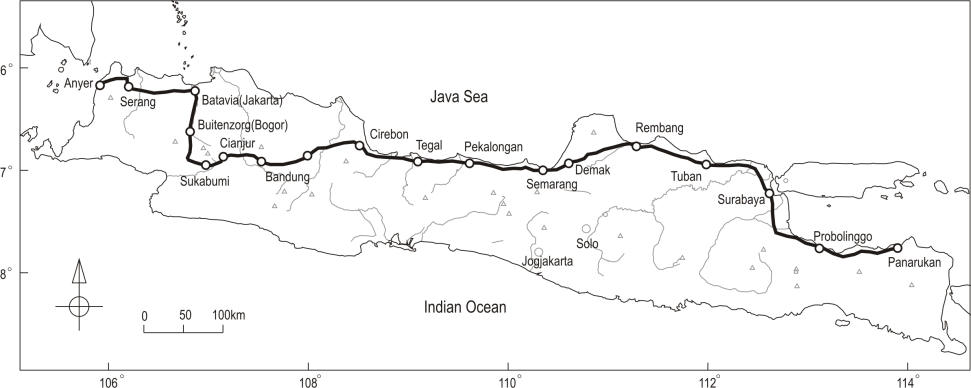

The beginning of modern roads in Java was the Great Post Road (or De Groote Postweg in Dutch or Jalan Raya Pos in Indonesian) of 1,000 kilometres long, between Anyer and Panakan located in the west and east ends of the island, which Daendels had constructed at the cost of numerous labour lives. In 1858, J. W. B. Money [37] who visited Java from England wrote in his Java or How to Manage a Colony that "along the chief lines of communication the roads are double, one for cattle, and one for horse and carriage traffic. The carriage roads are macadamized, and both the carriage and cattle roads are kept in excellent order. With the exception of the few short lines of railway in India, Java posting is the only civilized mode of land travelling in the East". He also wrote that "every twenty, thirty, or forty miles the traveller comes to a civil station, where he invariably finds a comfortable country inn, well supplied with wine, beer, European as well as native vegetables, good fresh bread, excellent poultry of all". Alfred Wallace who visited Java in the course of his tour around the Malay Archipelago wrote in his book [38], after describing the sceneries of rich fields watered by many branching streams, white buildings and tall chimneys of a sugar-mill and so on, that "the roads run in straight lines for several miles at a stretch, and are bordered by rows of dusty tamarind-trees. At each mile there are little guardhouses, where a policeman is stationed; and there is a wooden gong, which by means of concerted signals may be made to convey information over the country with great rapidity".

|

De Groote Postweg (The Great Post Road). Drawn by the present writer. |

"A wooden gong" mentioned in this passage was the so-called "slit gong", cylindrical wood with a slit along the centre, from which sounds were generated with a wooden hammer. Since the communication speed is determined by [the sonic velocity × distance] + [hammering time × the number of transmission points], the time required to send a message to a place of 500-kilometre distance would have been only more or less three hours, if the hammering time and the number of transmission points were assumed to be 30 seconds and 300 points, respectively. It is probable that this communication system was used, for instance, on the occasion of Pieter Erberveld’s rebellion to send warning from Batavia to remote districts. When I lived in Bogor, I bought a small gong of this kind, called kentungan in a souvenir shop at Cipadat Pass to the west of Bandung and used it at home to be informed of mealtimes, etc.

Back at Kota Station, one might wonder to see why the tracks at two adjacent platforms are excessively separated. While I was aware that, before the Second World War in Java, two types of gauges were used, the wide one (standard gauge) for trunk lines and the narrow one for small lines [39], I was once astonished when I heard in Bandung or somewhere that a young railwayman despatched from Japan Railway proudly said that the Japanese had done a good job during their occupation to unify the gauge system in Java. Although no document has been available, it seems that they had actually demolished the wide-gauge lines and replaced them with the narrow-gauge ones for the worse. It is hard to believe in this peaceful time, but when a Japanese army constructed a bridge on the River Kwai between Thailand and Burma, as is well known by the famous film [40], with the forced labour of Javanese recruits and Dutch and English prisoners, they carried not only locomotives and carriages away from Java but also rails by peeling them off from the existing railway lines in the land of Java [41]. When I once took a train from Jakarta towards Cirebon, I noticed that in some parts the embankment was apparently wide enough for double tracks while the line itself had a single track. That the space between platforms is excessively wide is common in other stations, Bogor, Bandung, Yogyakarta, Solo or elsewhere.

Gambir Station in Central Jakarta, rebuilt in the 1990s by demolishing the original building with a pair of twin clock towers, gives no image of old days when special trains were drawn up on the occasion of the Fourth Pacific Science Congress, vagabonds loitered after the independence as written in Pramoedya Ananta Toer's novel [42], etc. On the platform on the second floor, one may again notice the excessive space between the tracks. Is it for changing the tracks to wide-gauge in the future? Although some Japanese funds are used for the modernisation of the Indonesian railway system, it will be hardly sufficient to expiate their past sin.

Let us visit the National Museum located on Jalan Merdeka Barat across Independence Square. The first modern museum in Asia was created in the Batavia Society for Arts and Science, established in 1778, and the present white-marble building with Parthenon-style front design was open in 1868, constructed by the donation of J. C. M. Radermacher, one of the founders of the society. In the entrance hall are dozens of stone statues of Buddhist and Hindu deities, and in the courtyard, hundreds more statues both stone- and bronze-made are placed under the eaves of showrooms, which surround the open space. Thus, the museum is often called Museum Patung, or Museum of Statues. The statues include some pieces brought from ancient remains of Central Java where the Sanjaya and Sailendra kingdoms flourished in the 8th to the 10th centuries, and more from Singasari and other remains of subsequent centuries in East Java, the maintenance of which at local sites was difficult. Detailed legends of each piece are shown in both English and Indonesian.

In the showrooms on the ground floor, numerous collections gathered from all over the Indonesian archipelago are displayed, sorted into such categories as textiles, stoneware, earthenware, and others. Ceramics include some fine pots and plates made in Ching‑te‑chen, China, and Imari, Japan, while among antique weapons were traditional swords (keris) and spears. One is allowed to see gold and silver artefacts and various precious treasures from ancient kingdoms in the special upstairs room, if requested.

In my view, the most characteristic feature of this museum is that all collections of over 190 thousand pieces are purely those that have been gathered from the territory of Indonesia, with no single piece purchased from abroad as an attraction. It should be noted that during the Dutch time, they installed almost all treasures here, except some pieces carried to Leiden University for research purposes. Once, I was disappointed to see only a few collections from Indonesia in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, when I visited there with no background knowledge.

While it was rather common, for instance, for the English who came to India and other Asian territories during the colonial time to consider the colonies as the temporary place for their economic activities and return home after their retirement, a number of Dutch people lived and settled for generations in overseas territories without prejudice. In fact, among my Dutch friends are those whose father came from Palembang, South Sumatra, and whose wife was born in Tomoha, North Selawesi. Because the East Indies as well as Dutch Guiana (the present-day Surinam) and Curaçao Island constitutionally held the same status as the Netherlands since 1922 ( See Footnote 23 of Introduction), it was not unreasonable that, when the Netherlands were occupied by Germany in 1941, the then governor-general, Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer, proposed to move the seat of the monarch as well as the government in exile in London to Batavia, without anticipating the Japanese invasion, which took place in the next year; although the idea was not agreed by Winston Churchill, who worried about the long journey of aged Queen Juliana, or by the queen herself, who wished to stay near to the homeland.

I wrote above that the majority of historical relics in Indonesia were kept there, but there were some exceptions. In 1871, when the archaeological value of ancient remains and relics began to be recognised, several pieces of Buddha statues from Borobudur were presented to King Chulalongkorn of Thailand who visited there, in return for his gift of an elephant statue, which, having been placed in the front yard of the National Museum, was to give another nickname: Museum Gajah, or Elephant Museum. It is also well known that, earlier in the 1810s, during the British occupation, a stone monument in which the royal line of Airlangga’s kingdom that had flourished in East Java was inscribed was carried away by Stamford Raffles to India, and was to be called "Calcutta Stone". More than one thousand works of art and craft collected by Raffles are now possessed by the British Museum, donated by his executor, Rev. William Charles Raffles Flint. In Alfred Russel Wallace’s travelogue [43], it is written that, when he was admiring a carving of the Majapahit era and expressed a wish to obtain some such specimen, in Mojokerto, East Java, in 1861, he was surprisingly presented with that piece, a fine relief of the goddess Durga, the detailed sketch of which having been illustrated in the same book. (For Durga, cf. Chapter 5.)

|

A bas-relief of Hindu Goddess Durga acquired by Alfred Russel Wallace in Mojokerto, East Java. Reproduced from: Alfred Russel Wallace, The Malay Archipelago, the land of the orang-utan and the bird of paradise: a narrative of travel, with studies of man and nature, MacMillan & Co., London, 1886 (Google Books). |

The specific collections of super-antique value in this museum, the fossils of Java Man and other prehistoric finds shown in a special corner on the ground floor are really fantastic, inducing one to review the history of their discovery[44], [45]. It was in 1859 that Charles Darwin launched the theory of evolution inOn the Origin of Species [46] and foretold that "fossils of some intermediate species between man and ape would be discovered in the future". In 1887, Eugene Francois Dubois (1858–1940), born in Eijsden, Netherlands, who had studied anatomy in Amsterdam University but had a potential interest in archaeology, was stimulated by Darwin’s theory and came to the East Indies as a military doctor, abandoning a high position promised in the university. While working as a doctor, he tried some diggings in Sumatra in his spare time, but no such fossil was found in the initial years. Struck by this enthusiasm, the government made an arrangement for him to be able to concentrate on his search in 1890. He operated an excavation with scores of men at Trinil Terrace of Bengawan Solo, the river which was to be popular also by a song of the same name, and was rewarded by the discovery of some fossils of a tooth (Trinil 1) and a skull (Trinil 2, or Pithecanthropus 1) in 1891 and a fossil of a thigh bone (Trinil 3) in the next year, all of prehistoric man, and he named the species as Pithecanthropus Erectus. His claim that he had discovered the missing link was not accepted by others who doubted that the fossils might be of an ape or a man. Deeply discouraged, he retreated from arguments. It was three decades later, after the discovery of the Peking Man in China and Australopithecus in South Africa, that Dubois’ discovery was first recognised. It is hard to imagine nowadays that a government authority, namely the Ministry of Education and Science Japan, would approve such a treasure-hunting project as of Dubois. As a humble ex-scientist, I would like to praise the insight and magnanimity of anonymous officials in 19th-century Java who had boldly given support to the adventure of Dubois.

In 1910–40, a wide and large-scale survey was conducted in Java that led to the discovery of fossils, a Solo Man in Sangiran (1930–3), a head of an infant at Mojokurt (1936) and several more of Pithecanthropes at Sangiran. After the independence of Indonesia, the research was followed by Prof. T. Jakob, who later became the rector of Gajah Mada University, Prof. Sartono, Bandung Institute of Technology, and their colleagues. Although fossil specimens shown to the public in the National Museum, the Geological Museum in Bandung or elsewhere are said to be replicas, they do not look so to the eyes of ordinary people as the colours and defects have been precisely imitated.

It is away from Jagatara, the present-day Jakarta, but let me add a short report on my visit to Sangiran. The Geological Museum of Sangiran was found in a small village on the terrace of Bengawan Solo, located a 30–40 minute drive to the south of Solo city centre. Upon being ushered into the building by the director who kindly received my party visiting with no advance notice, I was amazed by numerous collections in which a gigantic tusk, four metres long, and an enormous jawbone of a mammoth were displayed along with fossils of other animals that contemporarily lived with Pithecanthropes, as I saw such specimens for the first time. Other interesting specimens were two pieces of flat, red-coloured stuff of 12–15 cm length and a grey-coloured, spherical stone of about 18 cm diameter. I was able to guess that the two flat stones were a chopper and a raw stone for that sort of tool, but the use of the spherical stone was hard to imagine. Given an explanation that it would have been a grenade for hunting animals, I was convinced that those who used such tools, and who might have been our remote ancestors, were not apes. The restoration of the head-part bone of prehistoric buffalo was going on in the laboratory, by assembling fossil fragments, many of them as small as 5 mm, by studying their colour and shape and filling the defective parts with gypsum, as if one is trying to solve a huge complicated jigsaw puzzle. It must be laborious work, but the Javanese researcher looked to be enjoying it.

|

Some collections of the Geological Museum of Sangiran. Skulls of Pithecanthropus (top) and stone tools (bottom). Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

With regard to the origin of man, what we were taught until a few decades ago was "the multi-regional evolution hypothesis", in which the apeman (Australopithecus) that originated several million years ago in Africa and evolved into "homo-erectus" 1.5 million years ago, spread over Eurasia 1 million years ago and continued to evolve in each region to "early homo-sapiens" and to "modern homo-sapiens", but the so-called "single-origin hypothesis" emerged in 1987 in which all "early homo-sapiens" that existed in Eurasia became extinct and the only one group that survived in Africa and evolved into "modern homo-erectus" spread over other continents 200 to 100 thousand years ago. According to the latter hypothesis based on computer analysis, the origin of mitochondrias of all modern women in the world can be traced back to that of one woman, called "Mitochondria Eve", who lived in Africa 190–140 thousand years ago. Some devotees to the second hypothesis say in such a tone as if the traditional research of hunting and classifying fossils, by dirtying one’s hands, were not of significance, but it is hardly agreeable to myself who has engaged in something like scientific experiments.

The visit of Mr. Yoshinobu Tokugawa

During my stay in Bogor, there was an occasion on which I attended (the late) Mr. Yoshinobu Tokugawa, a grandson of Marquis Tokugawa, the author of Journeys to Java. In January 2001, he gave me notice that he would come to Java, in response to my Christmas card of the previous December, in which I asked whether he could come to Java to trace the footsteps of his grandfather. Since the period he could spare for his trip was only five days, whereas Marquis Tokugawa had spent fifty days in Java (seven plus forty-three days) on his two journeys, I prepared a plan for him to visit several important spots as efficiently as possible. When I went to the National Museum to ask the director to receive his visit, she appointed Mrs. E., the head of Ceramics Division, to attend Mr. Tokugawa on behalf of the director herself, as she herself was scheduled to be abroad on the designated date. After going around the Bogor Botanical Garden, Bandung Institute of Technology, Borobudur and Prambanan remains near Yogyakarta, we were received by Mrs. E. at the National Museum. I met her for the first time and I was quite impressed that the scene of her guiding her guest looked good enough to be painted in a picture. After that occasion, she became not only my friend but my respectful teacher, and taught me many things about the history and culture of Indonesia. When I invited her to my house in Bogor, she was intently gazing at a portrait of a Javanese prince, which she had found in a book of old paintings painted by foreign artists [47]. To my question, which came suddenly to my mind, "Was he your ancestor?", she answered with a little hesitation, "Yes, he was my great-grandfather." I learnt that she was a princess, with the title of Raden Ayu, linked to the family of the Sultan of Yogyakarta, although she hid her bloodline and the title in her daily life, whilst the late Mr. Yoshinobu Tokugawa should have succeeded the title of Marquis, were not the traditional peerage system in Japan demolished after the Second World War under the American occupation. I reckoned this was the reason why the director of the museum had chosen Raden Ayu E. as her substitute among many possible candidates.

|

(The late) Mr. Yoshinobu Tokugawa and Mrs. E in the showroom of traditional textiles in the National Museum. Photographed by M. Iguchi, 2001. |

In Yogyakarta’s royal family, the sons and daughters of the sultan are given the title of Putra and Putri, respectively, those of the 3rd to the 5th generation, Raden Mas and Raden Ayu, respectively, and those of the 6th to 8th generation, Raden and Rara, respectively. Although the above rule is said to be more or less ambiguous in the Susuhunan’s family in Solo and the families of sultans in other lines, the titles are the evidence of noble descent, and gentlemen and ladies who hold them are paid respect by common people even today in Java, probably more than in countries in West Europe.

To the question, "Are there kings and nobles in Indonesia, despite the country’s structure as a republic?", I will answer that elsewhere.

Grand statue of Krishna and Arjuna

In the city centre of Jakarta, not far from the National Museum, by the roundabout in the southwest corner of Medan Merdeka (Independence Square), stands a magnificent bronze statue of Krishna and Arjuna, the former driving a chariot and eight horses and the latter in the rear seat holding a bow at the ready. It was created in 1987 by a famous Balinese sculptor, Mr. I Nyoman Nuarta, who had graduated from the department of Art, Bandung Institute of Technology. The eight horses are said to represent eight divinities who symbolise Asra Brata (the eight statesman’s virtues) [48] in Hindu philosophy, which the then President Soeharto favoured. I remember that the colour of the statue used to be whitish as it was originally made of polyester resin. Since the material was weathered, the statue was remade in bronze in 2003 at the cost of four billion rupiah (ca. 470 thousand US dollars). Although the large spending was argued at that time when the economy of the country, damaged after the Asian Economic Crisis (started in 1997), was yet to be healed, I appreciated the action of the government. The statue is widely known as the Arjunawiwaha Statue [49], but the reason is not certain to me because, if I am not mistaken, Krishna does not appear in the poetic Kakawin Arjunawiwaha (Arjuna’s victory) composed as a branch tale of the Ramayana in 14th-century Java, while both heroes do appear in the Bharatayuddha, an adaptation of the last chapter of Mahabharata, or the Mahabharata itself. (For old Javanese literature, see Chapter 6: Flowers of Java). In any case, the statue is one of the rare cultural monuments installed in the era of President Soeharto whose priority policy was economic development, whilst most of the monumental statues in the city of Jakarta are the relics of the first President Soekarno created to enhance the righteousness of independence.

|

The so-called "Arjunawijaya statue" at the southwest corner of Medan Merdeka (Independence Square). Photographed and permitted to copy by courtesy of Prof. N. Narayana Rao, Illinois University (http://faculty.ece.illinois.edu/rao/statue.html) and kindly permitted to copy. |

In President Soeharto’s era, a large public park of 240 hectares, called the Garuda Wisnu Kencana, with a gigantic, 150-metre-tall statue of Lord Vishnu mounted on the divine bird Garuda in the park’s centre, was planned to be constructed in Bali on the hill of Bukit Peninsula at the southern tip of the island, and Mr. Nyoman Nuarta, the sculptor of the Krishna–Arjuna statue in Jakarta was assigned to work on the new statue. It was in 2006, the year after the park’s opening, when I had a chance to visit there. Although the whole statue was yet to be completed due to the shortage of funds, the upper body of Vishnu and the head part of Garuda were already finished and placed separately on the ground. The two parts themselves measuring 20 and 18 metres high, respectively, were overwhelming in the environment, looking down at us, sightseers.

Some interesting spots in Jakarta

This essay is not aimed at being a travel guide, but let me introduce some spots that may have some atmosphere of old days. In front of the Jakarta History Museum (the old City Hall), across its front courtyard (now called Taman Fatahillah) is a restaurant-café called "Batavia Café", which is suitable to wet one’s throat with Pilsener beer, Bir Bintang, the heritage of Heineken, and to take a light Dutch-style lunch after visiting the museum. The year of construction of the luxurious, two-storey building, made of teak wood from the pillars to the window frames, is unknown to me, but, no doubt, a heritage from the good old days and the building itself has a museum-like value. There are numerous frames with the bromides of former stars, such as Marlene Dietrich, Marilyn Monroe, and other stars, as well as rare pictures of old sceneries and people, on the pillars and walls in the dining rooms, corridors, staircases and everywhere, but, in order to look at them for studying purpose, they must be sorted and ordered in one’s mind, as their placement is quite at random. Judging from the list of drinks and their prices on the menu, there would be a number of guests, in the evening, from Holland and other European countries who longed for the past, although I have not been there at dinner time.

|

Batavia Café (the late Mr. Yoshinobu Tokugawa, Mrs. E., National Museum, and Mr. A. B., Ministry of Industry). Photographed by M. Iguchi, 2001. |

Before Istana Negara (lit. National Palace, the former Official House of the Dutch Governor-General) on the way from Kota (Old Batavia), one finds a restaurant, Pondok Laguna, under the neon-sign of "gurame", at Jalan Batu Tulis Raya No. 45–47. Gurame, a freshwater fish, which resembles in shape a gourami for home-aquariums, and presumably belongs to the same family as the latter, but grows up to 30–40 centimetres, is a typical foodstuff of Sundanese cuisine served as gurame goreng (fried gurame) and gurame bakar (grilled gurame), both seasoned with chilli and spices. Since the quality of its white meat was extremely good for a freshwater fish, and has no muddy odour as of "ikan mas" ( lit. goldfish but more similar to crucian carp), I once placed a special order to roast the fish with only salt, as it was commonly done in Japan for sea fish. The result was good and I was quite satisfied with that taste. Every evening, the large dining room of the restaurant of some 200 square metres is full of gourmets who, in groups, are enjoying their favourite dishes, such as stir-fried beef and green kale, sapo tahu (beancurd soup), capcay (originated from Chinese chop suey, 雜采=mixed vegetables), various sate (skewer-roasted various meat), etc. While some hot Indonesian cuisines are not palatable for foreigners, the taste of this restaurant is sophisticated, or modified to be mild. I think their foods are better called "Makanan Butawi" (Batavian foods) rather than Makanan Sunda (Sundanese foods).

|

The neon-sign of a Sundanese restaurant, "Pondok Laguna". Photographed by M. Iguchi, January 2007. |

At Jalan Raden Saleh Raya No. 47, to the east of the city centre, is a restaurant named Oasis. The luxurious teak house with beautiful chandeliers and stained-glass, originally built in 1928 by a Dutch millionaire, Brandenburg van Oltsende, who owned tea, rubber and cinchona estates, as his private mansion, has such a history that the last Dutch governor-general lived here for a while during the Second World War, but the attraction of the restaurant opened in the 1970s is certainly the foods they offer. Although only one item is found on the dinner menu, one need not be worried, because the food, rijsttafel, is a full-course Dutch-style Javanese meal, which includes boiled egg with coconut sauce, beef cooked with spices, Indonesian-style chicken curry, sate of prawn, tempe (fermented soya-beans), fried banana and many others. They are carried by one dozen waitresses, who hold one dish each, to the table and one portion each is served on a big plate, around white steamed rice, which is first placed in the middle. Thus, there is no order in which to eat, even though it is a full course.

This style of serving by many waitresses is rather special, but the style of guests helping themselves to take portions as they like from bowls on the table is more traditional, as rijsttafel, or rice table, is said to have originated in old days in plantations that were remote from towns. I once had a rijsttafel dinner at the famous Gunung Mass Tea Plantation in West Java, being invited for a meeting, and enjoyed the rather informal dinner in a special atmosphere on the hillside, overlooking the vast scenery of tea fields. Rijsttafel has been transferred to Holland. When I was staying in Eindhoven, I found a special restaurant, called Jawa, near the Philips Headquarters, which was run by a gentleman who came from Java some thirty years ago. He told me that he visited his homeland every year to get spices. The taste was excellent and better than those in restaurants in Jakarta and Bandung, as the quality of meats and vegetables produced in the cool European province was superior to that in tropical Java.

Raden Saleh, which was put on the street of the Oasis restaurant’s address, was the name of the 19th-century painter, a pioneer of modern painting in Java who stayed for a long time in Europe. The hearsay that the Oasis building used to be his residence is wrong. The Raden Saleh Mansion, a gorgeous Roman-gothic house built on a near-by site was financed by his wife, Constancia von Mansfeld, a daughter of a German rich man. It is still of use today as part of a hospital.

|

A guest room of a coffee shop, "Bakoel Koffie". Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2007. |

At Jalan Raya Cikini No. 25, on the extension of Jalan Raya Raden Saleh, is a cosy coffee shop, Bakoel Koffie (lit. Basket Coffee), where my friend, Mr. B., has taken myself and Mr. and Mrs. E., in a recent year, saying that he had found an interesting place by chance. It was not only the Dutch-style spelling of the shop’s name and the logo mark of a charming country girl holding a coffee-bean basket upon her head, designed to fit the shop’s name and placed on every window glass, that provided an image of good old days. Both the interior decoration and furniture looked classic. At close sight, tables and chairs were recognised to be used ones, which would have been collected from old schools and offices, but they were revarnished in the same dark brown colour. The only game provided for killing time was the traditional "congklak", and neither the current electronic games nor chess sets, widely played ever since the Dutch time, were there, although bringing one’s own belongings seemed to be free as some customers were working on laptops in the back-side room. Under the eave of the small backyard hung a flag on which a history of coffee was printed as, "1000 AD: Physician and philosopher Avicenna of Bukhara is the first writer to describe the medicinal properties of coffee which he calls bunchum"… "1706 AD: The first samples of coffee grown in Java are brought back to the Amsterdam botanical gardens"… and "2001: Bakoel Koffie, started by Tek Siong’s great-grandchildren, open a shop in Jakarta, Indonesia". On the wall, there was a picture of an old Chinese man who, according to the shopkeeper, was Mr. Tek Sun Ho himself and commenced coffee-roasting business in Batavia in 1878.

The coffee served in this shop was the traditional "kopi tubruk" (Turkish coffee), prepared by pouring hot water over coffee powder in a cup and stirring. The sugar was also the palm sugar used in Java ever since ancient times. I assumed that "kopi tubruk" must be related to Tobruk, a strategic point in North Africa that was sieged by German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel during the Second World War, but I have had no answer yet to my own question why the name of the place was adopted for the preparative method of coffee. The coffee itself of this shop was rich in flavour, but was a little unsatisfactory to myself who prefers the traditional, deep-roasted, rather bitter taste.

Goods of foreign origin in Japan prefixed with "Jagatara"

Leaving the land of Jagatara, let me put some considerations on several goods imported into Japan during the Yedo Period (1503–1869) or before with the name of Jagatara. The most popular one among populace is Jagatara-imo (potato. Solanum tuberosum L), or Jagaimo for short, but, having operated some surveys, I was surprised by the ambiguity of its arrival. On the internet, there was an abundance of hits, but most of them were "copies of copies". Even the introduction on the homepage of the Japanese Society of Root and Tuber Crops, that "potato was carried to Nagasaki 400 years ago in the Keicho Era [around 1600 AD] by the Dutch who had then a base in Jakarta, Indonesia" was not better than that of a town talk. Among university homepages, I was not able to find any academic articles, among which were such strange descriptions as:

|

(1)

|

Such vegetables of the new-continent origin as pumpkin, chillies, maze and potato arrived in the Kamakura/Muromachi/Momoyama Era (G. University). |

|

(2)

|

Potato is said to have been brought to Nagasaki in the Keicho Era (1596–1614) by the Dutch. Some people assume it was in the 3rd year of Keicho, or 1598 AD (N. University and T. University). |

As to (1), it was impossible to include, at least, the Kamakura Era (1185–1333), because, even if the Nanboku-cho Period was added, the era did not persist beyond 1392, one hundred years earlier than the voyage of Christopher Columbus. In (2), it was not possible either that the Dutch brought them in 1598, because the first arrival of the Dutch ship, De Liefde, across the Pacific Ocean, wrecked on the shore of Usuki, Kyushu, with Captain Jacob Quaeckernaeck, Jan Joosten, William Adams and other crew members on board, was two years later.

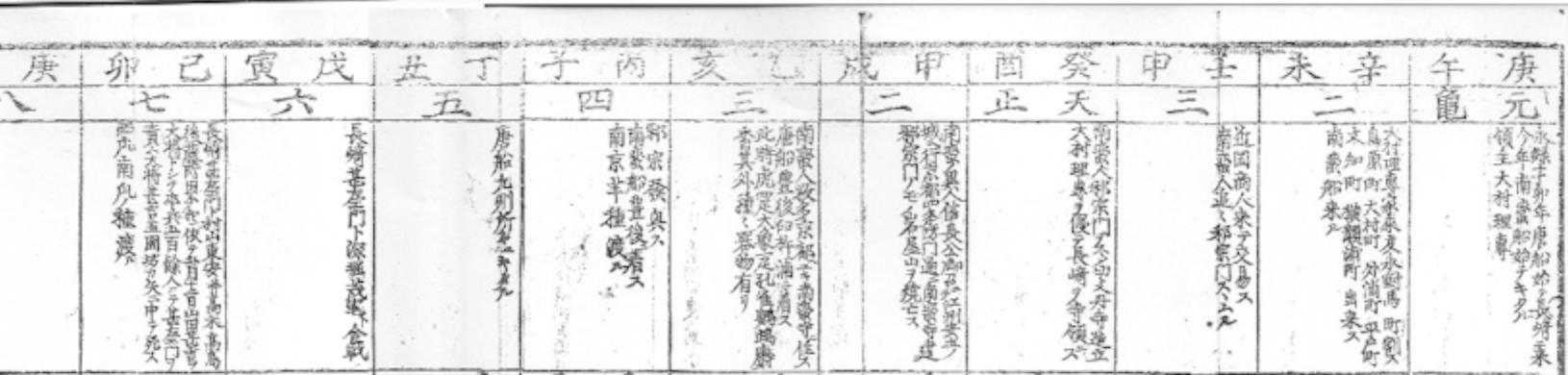

Since the first two Dutch ships from the south had departed from Johor and Patani, in Malayan Peninsula, in 1609 and 1611, respectively, the ship from Bantam in 1612 was the first one from Java. It was in 1614 that Ship Oud Zeelandia, accompanied by a yacht, Jaccatra, came from Jayakarta where they had set up their trading post three years earlier[50], [51]. Thus, it could not be impossible to imagine that potato was introduced in this year and was called Jagatara-imo or Jagaimo, provided it was really brought by the Dutch. While I was looking for more direct literature, I learnt that there was an old publication by Dr. Koutaro Shirai, a pioneer of modern botany in Japan, entitledConsiderations on the arrival of foreign plants [52]. In a copy of the rare book, which was luckily found in an antique bookshop, it read:

Jagatara-Imo (from Nibutsukou)

Name : Chinese: Yangyu (An Illustrated Textual Study on Plants), Japanese: Hassho-imo (Koshu), Seidayu-imo (Chichibu), Shouro-imo, Kinka-imo, Nanking-imo, Appra (Nibutsukou).

History : Grows wild in Andes, South America. Arrived in China sometime in the modern age. Nagasaki-ryaumen-kagami recorded that Nanking-imo arrived in the 4th year of Tensho (1576). The alias, Hassho-imo was born because 1 sho (1.8 litre) propagated into 8 sho (14.4 litre) a year. It is also called, Seidayu-imo, as a local magistrate, Nakai Seidayu, recommended to plant the plant for famine…

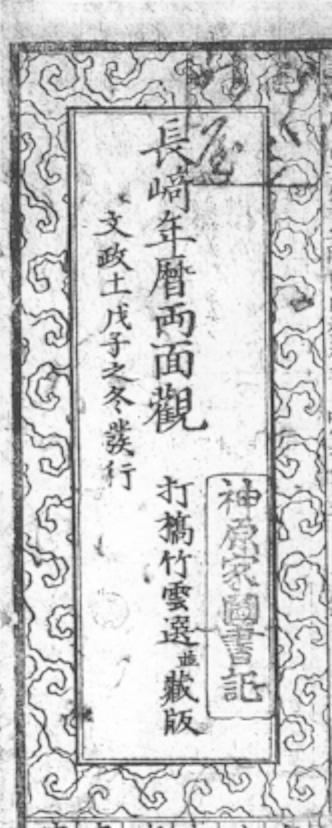

An alias, Appura is the corruption of the Dutch word, Aardappel.

I wished to see Nagasaki-ryaumen-kagami (lit. Nagasaki double-sided mirror), but the handwritten book authored by Chikuun Uchihashi in 1827, was not found in the catalogues of libraries, and one copy advertised in the antique book market was awfully expensive. Later, I learnt that the book was alternatively calledNagasaki-Nenreki Ryaumen-Kagami [53] and that a copy was held in the Library of Kagawa University. In the photocopy obtained by courtesy of the library, it was found in the column of 1576 that "Nanban-sen arrived at Bungo. Nanking-imo arrived."[53a] Although, according to a person from Nagasaki, Nanking-imo was locally a synonym of satoimo (taro, Colocasia esculenta) there, the very species, the arrival of which was recorded by Uchihashi as a special event, must be potato because taro of the Southeast Asian origin had existed in Japan since before the time of Manyō [54]. Generally, Nanban-sen, which literally means "south barbarian ship" and denotes a Portuguese ship, is distinguished from Oranda-sen or Ran-sen (a Dutch ship).

After some while, I found a booklet entitled Nagasaki-kotohajime (Nagasaki origins) [55] in which there was a description that "in a tradition, potato had arrived in Nagasaki in the 4th year of Tensho (1576) and was planted in the herb garden of Todos Os Santos Church". Although no reference was given, the year, 1576, agreed with the year in Nagasaki Nenreki Ryaumen-Kagami. The Todos Os Santos was a famous Jesuit church built in 1569 in Nagasaki but was destroyed in 1614–19.

Thus, I would conclude that potato was brought to Japan by a Portuguese ship in 1576 and acquired the brand name, Jagatara, to be called Jagatara-imo or Jagaimo.

In the above booklet, it was written that "the potato was also called Barei-sho (馬鈴薯) as it came from Malay Peninsula". I have thought of this possibility, as a kingdom prospered at Patani, in the northern part of the peninsula since the 14th century where Portuguese and Dutch ships often called in the 16th and the 17th centuries, respectively. In fact, the departing port of Oranje (schip) and Brack (jacht), which came to Nagasaki in 1611, were there, but there was no evidence that they brought potato. As far as I have checked, the common phonetic expression of Malay or Malaya in Chinese was 馬來, and no instance of being written as "馬鈴" was found.

In Nibutsu-kou, or Kyukou-Nibutsu-kou (a study on two items recommended to prepare for famine) [56], cited in the above mentioned book was authored by a 19th-century scholar, Chō-ei Takano (1804–50), mostly dictated by his disciple, the author picked up potato and soba (buckwheat) as useful plants to prepare for famine, and described the methods of their cultivation and cooking in great detail, after the introduction of their origins.

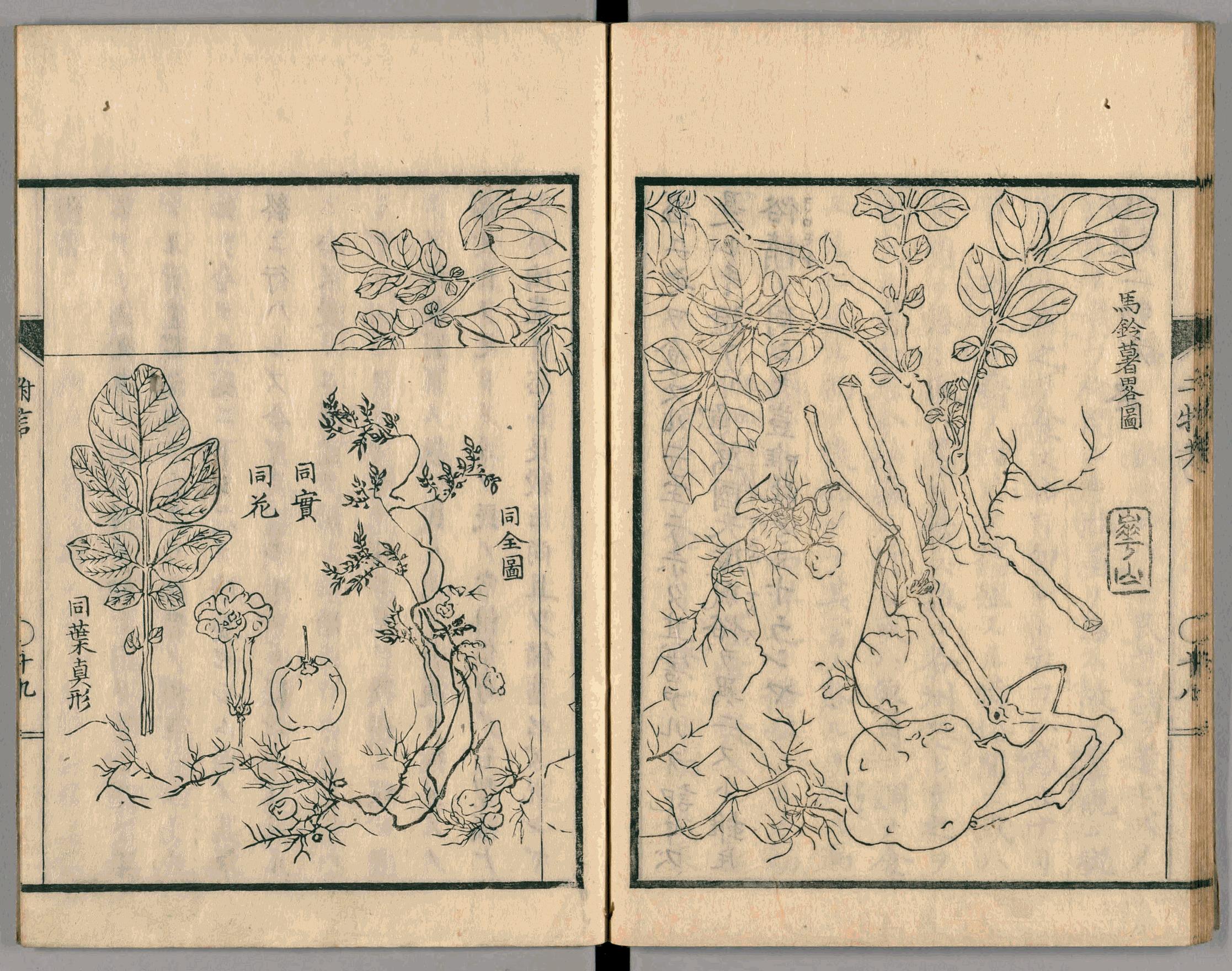

|

"The illustration of potato", by Kazan Watanabe (a famous painter) for the Chō-ei Takano’s Nibutsu-kau, 1836. Reproduced from the website of National Diet Library's Digital Collection, http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/2536207. |

Potato is cultivated in Java Island, but the suitable places for the vegetable of cool Andes origin are limited at highlands above 1,000 metres from the sea-level, such as Lembang at the mountainside of Mt. Tangkubanperahu in West Java or Dieng Plateau in Central Java. Once I obtained a gunnysack full of potato in Dieng when I visited there. The quality was very good, so I distributed some portions to my neighbours.

In A study on the arrival of foreign plants was Jagatara-Suisen, after Jagatara-imo.

Jagatara-Suisen

Name : Chinese: Unknown, Japanese: Jagatara-yuri (lily).

History : Originated in Mexico and arrived in the Era of Ka-ei, according to Souhon-dzusetsu. The notes in Hakurai-souhon-meisho that "Jagatara-yuri. The shapes of both the leaves and flowers are similar to those of knight’s star lily and its bloom colour is pale-red" would be on Jagatara-lily, although the colour was not necessarily agreeable.

Today, this plant is called amaryllis in its English name. Although the era of Ka-ei (1848–54) was already in the last stage of the Edo Period (1603–1868), "Jagatara" must have still been an exotic, attractive brand in Japan. Amaryllis is a popular flower also in Java.

In dictionaries, "Jagatara-jima" and "Jagatara-mikan" were also found.

Jagatara-Jima (Jagatara-Stripe)