Bells ring around the Dutch quarter.

Jagatara O-Haru is wet and sobbing,

The gong of a departing boat echoes. [1]

Jagatara – The Destination of Haru

| Rain pours over

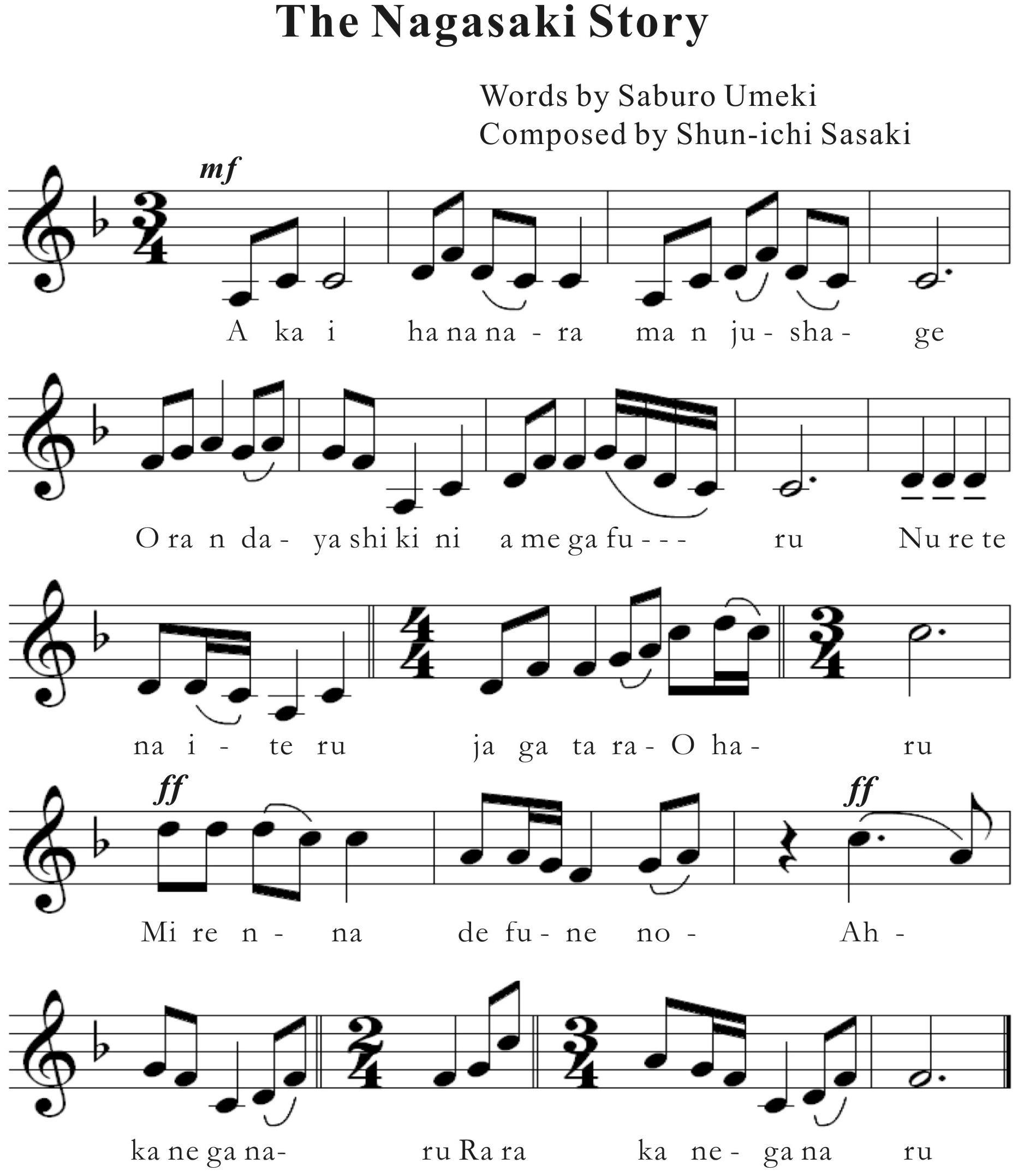

red amaryllises, Bells ring around the Dutch quarter. Jagatara O-Haru is wet and sobbing, The gong of a departing boat echoes. [1] |

It must have been on the eve of the last day of the Great East Asian War that I first heard this song, although that it was on that particular date, 14th August 1945, had no significance. I remember that a peaceful atmosphere was present to celebrate the three-day Buddhist Bon festival that still remained in a remote countryside where my family had evacuated from an air-raided city, allowing young villagers of both sexes to show their amateur plays and songs on the stage temporarily situated in the school ground. The slow and sorrowful melody of the song in a minor key sounded unfamiliar to the ears of a small boy and was imprinted in his mind, as all other songs heard at that time were stirring, military songs. When I asked my uncle about the meaning of the verse of the seven–five syllables, he, a country gentleman who had broad knowledge for a villager, taught me that it was written after the episode of a girl of mixed parentage, called Haru, who once upon a time was born in Nagasaki and was exiled to Java, according to the anti-Christianity policy of the Tokugawa Shogunate government. Although I thought over the fate of the tragic heroine in my infant brain and imagined the scenery of the southern island where palm trees grew as I saw in a “Java stamp” in an album, I never thought of visiting there in the future and living there for some years. In the 1980s, there were several occasions to travel to Indonesia, but I was only fascinated by exotic sceneries and cultural things that I glimpsed in the breaks from work. When I arrived there again in 1990 to stay for a certain period and I thought about my family, which I had left 7,000 kilometres away in Japan, the memory of Haru’s story was suddenly revived. According to a letter from my wife whom I had asked to investigate the details of “O-Haru’s song”, the correct title was ‘The Nagasaki Story’, written by Saburo Umeki and composed by Shunichi Sasaki in 1939, and the song became popular throughout the country. There were three more verses after the one I remembered, which could be translated as:

| 2. |

Moon cast a pale light over the stained glass. Because her father was a foreigner, Holding a golden cross in her mind though, The girl of her blooming age is melancholic. |

| 3. |

Night falls over the pavement On the hill of Nagasaki, Towards the offshore of Deshima [2] , The soul of her mother sails on a straw boat. |

| 4. |

Letters she writes come to Hirado From hundreds of miles away, Why Jagatara O-Haru does not return? The bell of Santa Cruz rings. |

The score of ‘The Nagasaki Story’ (Song). The staff notation from Chikusa Publishing’s Free Library. The words were added with reference to Zen-on Kayokyoku Zenshu Vol.1, 2006. |

Later, I learnt that the story was mentioned in many books. In his travelogue, A Book of Southern Countries published in 1910 [3], Yosaburo Takekoshi, an eminent statesman and historian through the eras of Meiji, Taisho and Showa, wrote his emotion as:

“Batavia where the Jagatara Letters written by Princess Jagatara, most informative of the overseas situation in the era of the Shogunate regime, came from, where Japan had a long relationship as the name of Jagatara-imo (potato) originated and where the traditional batiks as valuable as many hundred thousand yen per one square inch were produced, is now underneath my foot!”

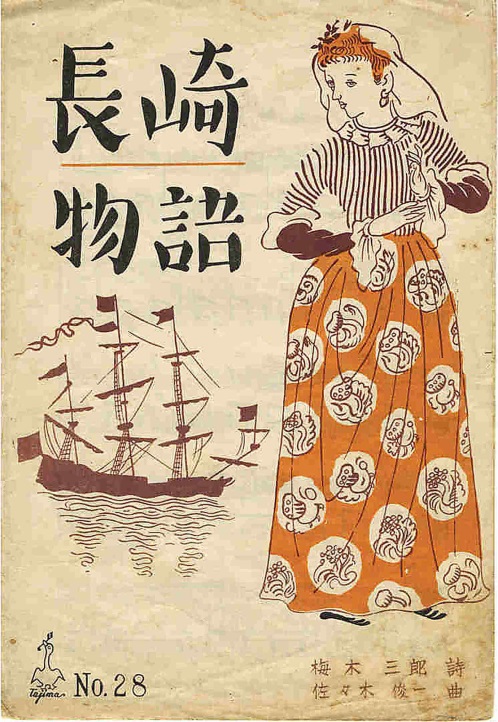

Although Haru was neither a daughter of a noble nor a lord family and the “Princess Jagatara” was just a flowery phrase characteristic to the author known as a rhetorician, she must have been a beautiful girl of mixed parentage. The portrait on the cover of the score of ‘The Nagasaki Story’ painted by an anonymous painter gives us a good image.

| The cover of the score of ‘The Nagasaki Story’, written by Saburo Umeki and composed by Shunichi Sasaki in 1939. By courtesy of Mr. M. Miyagawa, Nagasaki Prefecture. |

Marquis Yoshichika Tokugawa, who visited the same place in 1921, wrote in his famous travelogue, Journeys to Java [4], as follows:

“When the Shogunate government banned Christianity in September of the 15th year of Kwan-ei Era [the 16th year of Kwan-ei = 1633 AD], amongst those people who did not agree to convert their religion and were expelled from Nagasaki was a girl called O-Haru. Being home-sick for Japan in exile in the foreign land, she wished to grow plants of her parents’ country to remember her home where she would never visit again. She wrote a letter requesting some seeds and sent it by courtesy of a Dutch kabitan [5]. The letter tells us how she was lonely and nostalgic. There must have been many other people who bore a grudge against their fate and whose bones were buried in this soil.”

Although it was an incident that would have been suitable to be adopted to the title of a joururi (dramatic narrative) or an ukiyo-zoushi (lit. illustrated books on fleeting life), neither Monzayemon Chikamatsu wrote a playbook nor Saikaku Ihara published a picture book, unlike the contemporaneous “Kokusenya-gassen” (Coxinga’s battle) in which Watōnai, alias Tei-Seikō (c. Cheng Cheng-koeng), born of a Chinese father and a Japanese mother in Nagasaki, fought against Qing in an attempt to revive the Ming dynasty, presumably because they were afraid of the prosecution by the Shogunate government. Probably for reaction, a number of criticisms boiled up after the Meiji Restoration and the reopening of the country.

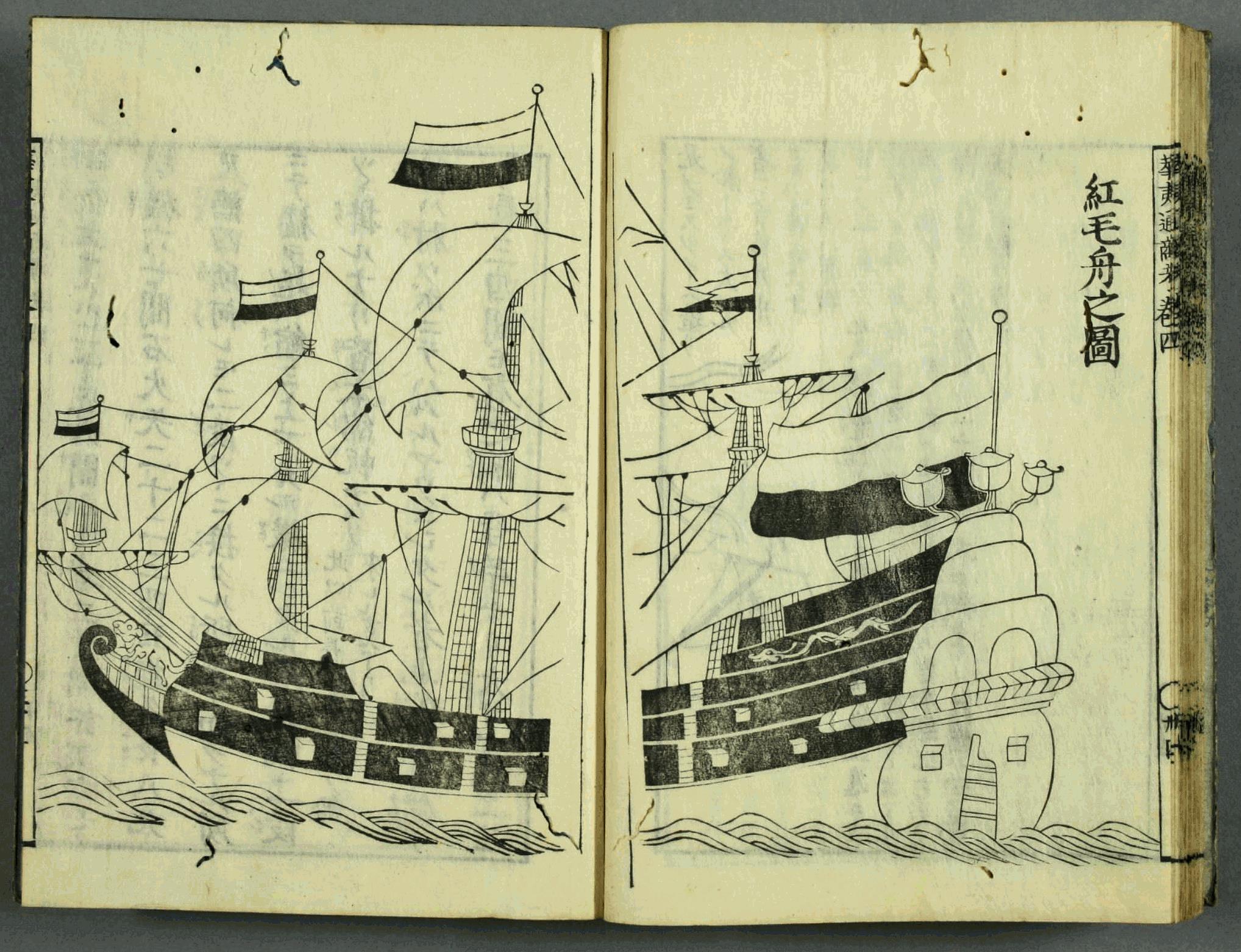

The tragic story was originally written in Nagasaki Night Tales (Nagasaki Yobanashi Kusa) [6], a collective volume of essays authored in 1719 by Nyoken Nishikawa, an astronomer and geographer in the mid-Edo Era, after his retirement. In the prologue of an article entitled “The deportation of the children of Red-hairs [7] – A Jagatara letter attached”, the author wrote that “among eleven male and female descendants of Red-hairs in Nagasaki and Hirdo deported in the 16th year of Kwan-ei Era [1639] was a girl called Haru who was born in Nagasaki and brought up by her relatives. She was beautiful and tenderhearted and good at writing. Three years after her arrival at Jagatara (咬𠺕吧), she was so homesick that she asked a Dutch mail boat to send a letter to Japan”, and cited the so-called “Jagatara-letter of Haru”, which was to be praised later by Takekoshi as one of the finest proses in history.

|

It was in October, the month of tempest when a bitter storm blew and the evening moon was hidden, that in the pouring shower I left my homeland for a one-way journey to this unknown land. It is far away across the oceans, but my mind can cross over. The way to Yamato[8] which I think of is distant though I am able to travel in my dream every night. … (A middle part omitted) … Please, send me the seeds of pine, Chinese arborvitae, Japanese cedar and belvedere. I am sorry that this letter may not be easily readable because I am writing it being choked with tears. Dawn is near and the summer insects seem to have awakened. I have never worn the clothes of foreigners. How I can be like a barbarian, even though I am in a foreign land. Oh, I miss Japan, I would like to see you. Haru, from Jagatara

|

In the epilogue, Nishikawa wrote, “In her nubile age, Haru married a Chinaman and had children. She had frequently sent letters to Japan and died around the 9th year of Genroku [1696] at the age of 76 or 77.”

| A Dutch Ship in Nyoken Nishikawa’ book. Kyurinsai Nishikawa (Ed.), Accounts on Foreign Trades – Enlarged edition Vol. 1-5, Kansetsudō, Kyoto 1708. Reproduced by courtesy of the Waseda University Library, from: http://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/i13/i13_00581/i13_00581_0004/i13_00581_0004.pdf, by courtesy of the Library. |

The original copy of Haru’s letter does not now exist, whereas several pieces of contemporary letters arrived from Japanese deportees remain. Although Nagasaki Night Tales, which vividly recorded such events as “The prohibition of the voyage to overseas” in the 12th year of Kwan-ei (1630) and “The deportation of the children of Barbarians” in the next year, is regarded as a reliable historical resource, whether the letter of over 3,000 characters written in a classic style with citations of many phrases from ancient poems and proses had really been produced by a girl of seventeen years of age is said to have already been questioned soon after the death of Nishikawa by his disciple, Saisuke Yamamura, and a famous Dutch-studies scholar, Gentaku Ootsuki.

On the other hand, the aforementioned Yosaburo Takekoshi wrote in an article, entitled “The tragedy of Princess Jagatara” contributed to a journal in 1926, as follows [9]:

“Recently opinions that question the real existence of the author [of Haru’s Jagatara Letter] have been raised from the viewpoint that such a skilful letter could not have been written by a young girl, but I am not agreeable. Firstly, a devoted, pure scholar, Nyoken, who made efforts to introduce the situation of the West to people in Japan prior to Hakuseki Arai, was not a kind of person who made an apocryphal work. Secondly, there is no reason that only highly educated scholars can write a letter that can make a deep impression. Even a young girl could touch people’s hearts by her writing brush [or pen] at the extremity of her grief for her love for her homeland, family and friends. Thirdly, the death register of a family which proves the existence of Haru has been discovered by Mr. Koga, my friend.”

With regard to the letter of query in Nagasaki Night Tales, Prof. Iwao wrote in 1987 in his book [10],

“Detailed descriptions regarding the situation of people in Jagatara and the consideration to her close relatives in Nagasaki would have been true. Nishikawa who was 22 years younger than Haru and whose earlier 51 years overlapped with Haru’s life must have heard of the letter or seen it himself. He might have rewritten the letter in such a way as to arouse the interest of audience.”

While Nagasaki Night Tales was the only source of information on Haru in Japan, many documents that prove her to have been a real-life person remained in the Dutch side. In the eras from Meiji to Showa, the pioneer of the history of the Japan–Holland relationship, Dr. Naojiro Murakami, discovered the name of Haru in the list of passengers on De Breda (departed Nagasaki in 1639) in the National Archive in Den Haag, and Haru’s marriage certificate and some other documents in the Regional Archive in Batavia [11]. The study of this field was followed namely by professors Madoka Kanai and Seiichi Iwao and other scholars. In particular, Prof. Iwao visited Batavia several times in 1925–39 to survey massive documents and found some contracts and wills signed by Haru herself. Thus, the outline of Haru’s life has been revealed (Table 1).

| Table 1 Personal history of Haru (Jeronima Marino)* |

|

1625 (Kwan-ei 2) |

Born in Nagasaki. Father: Nicholas Marino (an Italian pilot), Mother: Maria (Japanese woman). She registered herself as a widow of an Englishman. Elder sister: Man (Magdalena). |

|

31.10.1639 (Kwan-ei 16) |

Deported to Batavia onboard ship De Breda with her mother, sister and the sister’s son. The son was put into the care of someone in Taiwan (because he was too weak to continue voyage). |

|

1.1.1640 (Kwan-ei 17) |

Arrived at Batavia. |

|

1642 (Kwan-ei 19) |

Sent a letter (introduced in Nagasaki Night Tales) to Japan. |

|

22.1.1642 (Kwan-ei 19) |

Man (Magdalena) married Buzayemon, a rich Japanese businessman. (Man died probably in 1644) . |

|

1625 (Kwan-ei 2) |

Born in Nagasaki. Father: Nicholas Marino (an Italian pilot), Mother: Maria (Japanese woman). She registered herself as a widow of an Englishman. Elder sister: Man (Magdalena). |

|

29.11.1646 (Shouho 3) |

Married to Simons Simonsen (born in Hirado in 1624, a Junior Merchant of VOC, and had three sons and four daughters*. |

|

1647 (Shouho 4) |

Mother, Maria, died. |

|

1661 (Kwanbun 1) |

Lived in Jonkers Street (according to the will of Michiel Diaz Sobe). |

|

14.12.1663 (Kwanbun 3) |

Simonsen declined to be transferred to Holland. Later, he was promoted to the Harbour Master of Batavia. |

|

13.2.1665 (Kwanbun 5) |

Will signed by Simons and Haru. |

|

5.1672 (Kwanbun 12) |

Simons died. |

|

7.5.1681(?) (Tenwa 1) |

Sent another letter (signed by Haru, widow of Simons) to Japan. |

|

17.5.1692 (Genroku 5) |

Will. |

|

20.3.1697 (Genroku 10) |

Revised the will. |

|

4.1697 |

Died at the age of seventy-four. |

|

A

Extracted from: Seiichi Iwao,

A sequel to: The study on the Nangyang Japanese town, Iwanami-shoten 1987

(岩生成一「続・南洋日本町の研究」,

岩波書店 1987). |

With reference to the study of Prof. Iwao, it is evident that the comments on Haru by Yosaburo Takekoshi, Marquis Tokugawa and others in earlier times were full of speculations and assumptions. Nagasaki Night Tales itself seems to have some errors, although it described the truth as a whole. First, the phrase in the prologue that Haru was brought up by her mother's relatives implied that she was an orphan, but her mother was actually alive and embarked on the same boat with Haru and her other daughter, Man (Magdalena). The description that Haru married a Chinaman written in the epilogue was not true as her partner was a young man, named Simons Simonsen, born from a European father and a Japanese mother in Nagasaki and deported to Batavia like Haru. The age of her death was four or five years different, although that might not be important.

Let us dare to see the words of ‘The Nagasaki Story’, which was most influential to popularise the story, although they were written by Saburo Umeki, a writer of Tokyo Nichi-Nichi Shinbun (Tokyo Daily Newspaper), for mere entertainment purpose with no academic insight. The writer misunderstood whether Haru’s mother was already dead, probably following the description in Nagasaki Night Tales. He imagined that red amaryllises were in bloom, but the flowers must have already wilted as the actual date of their departure was 31st October in the Gregorian calendar. That the bell of Santa Cruz rang was an obvious error. Before the promulgation of the Christianity Prohibiting Edict in 1614, there were more than ten churches in Nagasaki, including the famous Todos os Santoz (existed 1569–1619), and one church called Santa Crus Temple really existed[12], but they all must have been deconstructed twenty years earlier than the year of the deportation of Haru and others in 1639 [13].

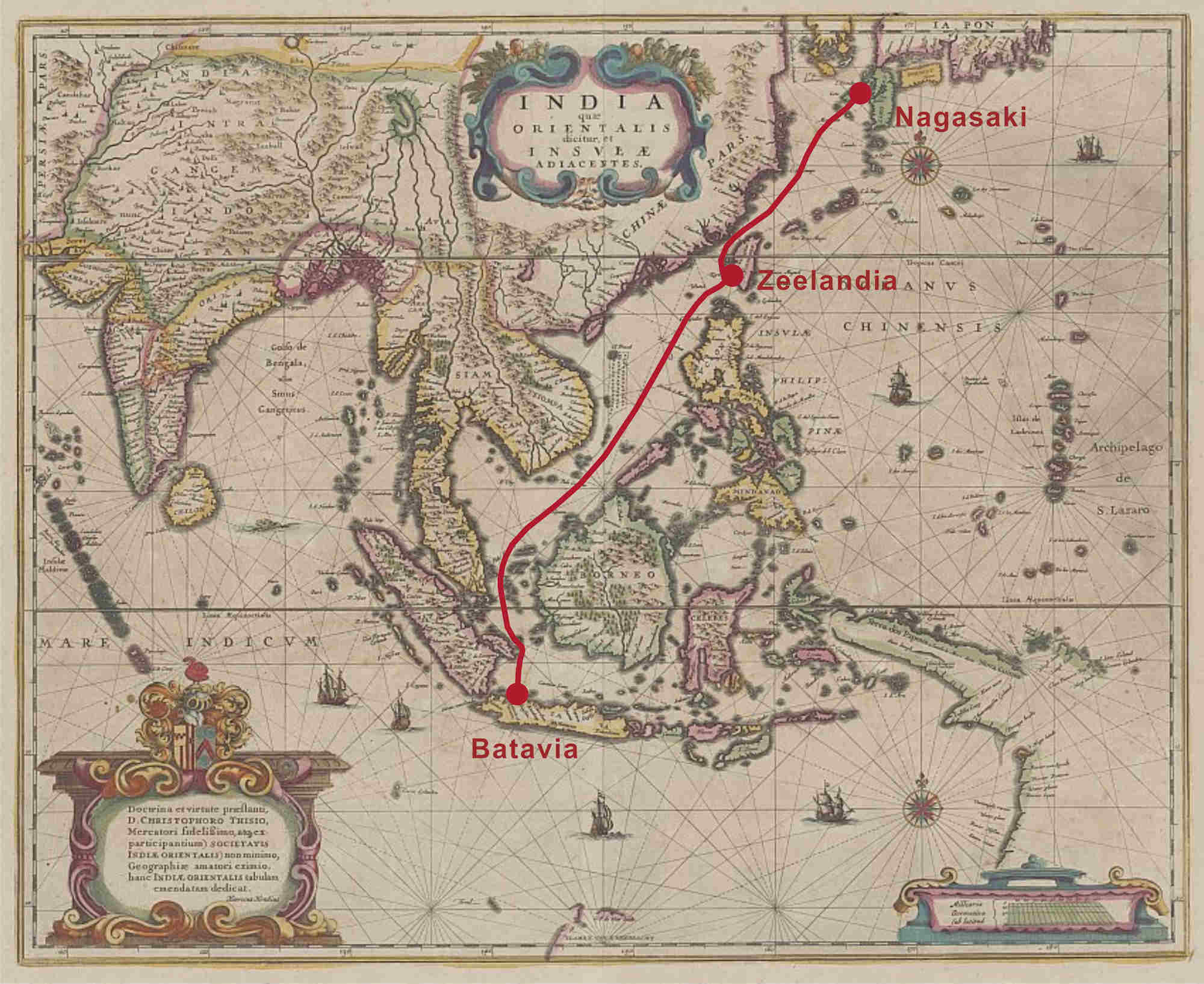

The ship on which Haru and her party embarked, De Breda, named after a town in southwest Holland [14], departed Nagasaki on 31st October 1639, docked at Zeelandia [15] in Taiwan and arrived at Batavia on 1st January in the next year. It was a voyage of 4,000 sea-miles distance, which took two months. The passengers included Haru herself, her mother, Maria (Japanese name unknown), her elder half-sister, Man (Magdalena), and other children of Dutch and English fathers and Japanese mothers, the total number being eleven (or thirty-one passengers including other foreigners and their wives, according to the Dutch-side record). Maria registered herself as a widow of a protestant Englishman, not as that of a Catholic Italian, probably because she had thought until the last moment that pretending to be so would give her a chance to be able to stay in Japan, although she and her daughters were eventually deported.

| The sea-route of De Breda from Nagasaki to Batavia via Zeelandia (1639). |

The map, “India quae orientalis dicitur, et insulae adiacentes” by Hendrik Hondius (1597–1651), Amsterdam, was adopted, by courtesy of the National Library of Australia, from the Library’s Item Number RM 174. The year of print, 1639, coincides with the year of the departure of Haru and other deportees sailed from Nagasaki. The route (estimated) has been added by the present writer.

How was the situation of Jagatara at that time? Twenty years having passed since the Dutch first built a fortress, the port was bustling with arriving and departing ships and the town was developing fast, the population having increased to 8,000 in 1632 from only 2,000 in 1620 [16].

Let us briefly review the history. The harbour on the mouth of the Ciliwung River, the origin of the present-day Jakarta, was an important port ever since the time of Tarumanagara Kingdom, which prospered in the 4th to 8th centuries, and later called Sunda Kelapa. In the 15th–16th centuries, it was the main outer port of the Pajajaran Kingdom (1482–1579), the capital of which was located in Pakuan (the present-day Bogor), and the direct trade with Western countries started in 1513 when the first Portuguese ship arrived there. It was the time when Moslems who had risen in Central Java and crushed the Majapahit Kingdom and already obtained Cirebon in the northeast part of the Pajajaran’s territory. To prevent the further expansion of the Islamic power, Pajajaran had signed a defence treaty with Portugal in 1522, but the construction of the Portuguese fort had not been finished before the Moslems, led by Fatahillah (alias Faletehan), came to attack Sunda Kelapa in 1527, after seizing Bantam, another good port located in the west part of the Pajajaran’s territory, in the previous year. After that, the Portuguese could not contact the land-locked Pajajaran and continued their activities in the East Indies with their base in Malacca, which they had acquired earlier in 1511 (until it was taken by the Dutch in 1641). The capital of Pajajaran, Pakuan, fell to the hands of Moslems and the kingdom perished in 1579. In a book published in Ming Dynasty China in 1617, An Account on the East and West Oceans (東西洋考) Vol. 3, by Chang Hsieh, it is correctly written as:

|

“Kelapa is a dependency of Bantam where one can reach in half-day [from the latter].”[17] |

Sunda Kelapa was renamed, by Fatahillah, Jayakarta (literally “big victory”), or Jakarta for short [18]. Jayakarta was corrupted as Jaccatra in Europe and as Jagatara in Japan. The three Chinese characters (咬𠺕吧), which Nyoken Nishikawa applied for Jagatara, was the phonetic transliteration of Kelapa, of Sunda Kelapa, and was of use in Japan to call the town, and often Java, for a long time even after it was again renamed Batavia in 1619.

It was in 1596 when a Dutch ship came to Java for the first time at the port of Bantam. The event was four years earlier than the arrival of De Liefde to Japan, wrecked at the shore of Usuki, in the present-day Ooita Prefecture, Kyushu, with twenty-four survived men out of the initial 110 crew members, including Captain Jacob Quaeckernaeck, Jan Joosten, the sailing master, and William Adams, an English-born sea pilot. Jan Joosten was to be remembered by the name of a place, Yaesu, in the present-day Tokyo, whilst William Adams was to become famous with his Japanese name, Anjin Miura. The first voyage of the Dutch to the East Indies was also a hard one as the number of crew who managed to return home was only eighty-seven out of 240 members who were initially on board. Although the amount of pepper and other products obtained was not large, interfered with by the Portuguese, they earned some profit in Holland, urging many small merchant groups to collect funds and despatch fleets. It was soon realised, however, that the provision of large fleets was necessary to cope with the Portuguese, who had been active in Asia since one century earlier by reaching Calcutta in 1498 and founding a base in Malacca in 1511, and the English, who had defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588 and were beginning to explore the Orient. In 1603 under the charter of Prince Maurits van Nassau, the Dutch established the United East India Company (VOC), known as the first model of the modern joint-stock companies, to send strong fleets and opened a trading house in Bantam in the same year.

To avoid troubles with the English in Bantam, they built a new fort in Jayakarta and moved their trading centre there in 1611, but the English also came to Jayakarta four years later. In February 1619, the English attacked the Dutch fort in alliance with the local governor of Bantam, Jayawikarta. It was during the absence of the governor-general of the VOC, Jan Pieterszoon Coen, who had temporarily retreated to Amboyna in the Spice Islands, where they had another trading post, in December of the previous year, by anticipating the raid of the English led by Admiral Thomas Dale. Despite frantic efforts of Pieter van den Broecke to defend the fort, it fell to the hands of the English. Coen, who returned there with his re-equipped fleet in May, recovered the occupied fort after a hard battle and controlled the town. He built a new fort, Fort Batavia, and named the town also Batavia after the Latin word, Bataaf, for Hollanders. Batavia was attacked twice in 1628–9 by Sultan Agung of the Mataram Kingdom, which had risen in Central Java, but successfully routed the enemy and Batavia became the stronghold of Dutch activities in the East Indies.

|

Wayang dupara puppets of Sultan Agung and Jan Pieterszoon Coen. Photographed by M. Iguchi at Jakarta History Museum, September 2006. The board on the left-hand side explains, “The wayang dupara tells the invasion of Sultan Agung, King of Mataram, in 1628 and 1629 to Batavia, which was then controlled by the Dutch.” Wayang dupara was a new type of wayang (shadow play) depicting episodes from the history of the New Mataram Kingdom. (See Chapter 6.) |

From the middle of the 16th century to the promulgation of the National Isolation Edict by the Shogunate government in 1639, some number of Japanese went to Southeast Asia on board Portuguese ships and Goshuin-sen (government-licensed ships), but those who settled there were not many [19]. After opening their trading house in Hirado in 1609, the Dutch recruited Japanese men to fulfil the shortage of labour and military force in Asia, the number of officially contracted emigrants between 1613 and 1621 being as many as 225 [20]. As Europeans who came to Japan after turning around the Cape of Good Hope and landing at the coasts of India and Southeast Asia were surprised to find a highly civilised society in the Far East [21], there were many clerical workers with the abilities of reading, writing and arithmetic, whereas most ordinary people were illiterate even in Europe. The skill of artisans who were trained in the construction of temples and castles was superior to the European masters and, above all, freelance samurai were valorous fellows who lived through actual fighting in the Age of Battles. In fact, among the army of Coen, which recovered the fort of Jayakarta, were fifty Japanese mercenaries beside 400 Dutch soldiers, and the defence force of the same fort, when it had fallen to the hands of the English–Bantam ally, had twenty-five Japanese men. Indeed, in 1618–19 Portugal, Spain and China, whose vessels were attacked by Dutch ships, entreated with the Shogunate government to prohibit Dutch (and English) ships to carry Japanese military persons.

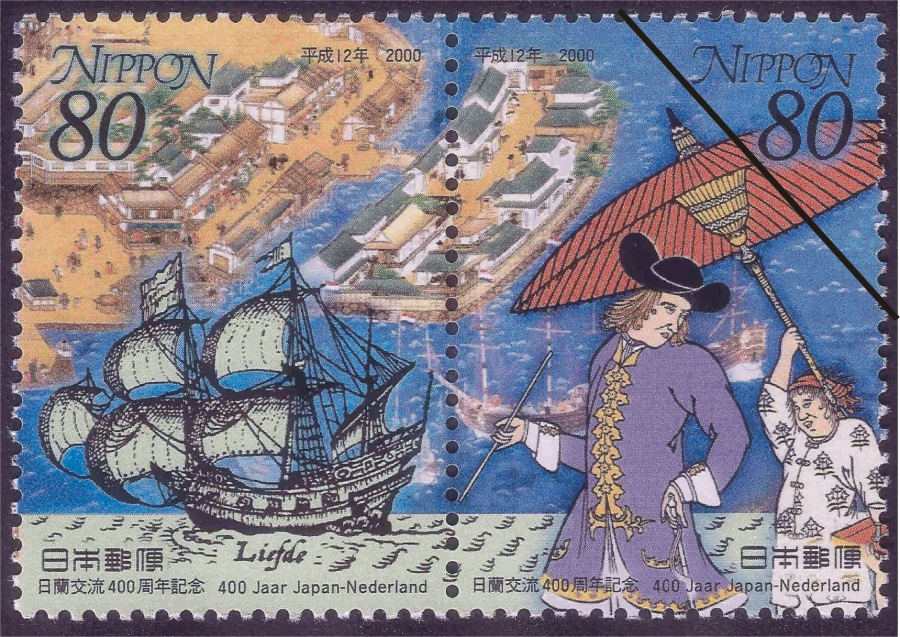

| A commemorative stamp of Japan Post for the 400th Anniversary of Trade Relations between Japan and the Netherlands. |

The ship, De Liefde, which arrived in Japan in 1600 AD and the Deshima Island in the background, from “Kwanbun Nagasaki Folding Screen” 1673. The Dutch Kabitan with a Javanese servant, from a coloured woodcut: ‘A picture of a Dutchman’, Nagasaki-Hariya, Houreki Period (1751–64).

The Dutch also recruited many Japanese women. Since it was the time when the voyage to distant Asia was so dangerous that losing some vessels in fleets by storms and sea-battles and some crew members and passengers by disease was common, the emigration of “normal” females, not to say those from upper- and middle-class families, from their fatherland was hardly expected. All of those who voluntarily came were “light women”, as the first governor-general, Peter Both, had petitioned the Herren XVII in 1612, “not to allow any more of them [light women] to emigrate from the Fatherland, since there were too many of them there already and those females led scandalous and unedifying lives to the great shame of the nation”[22]. In such a situation, men had to find their partners among local women, but most of the Javanese parents who were already Islamised did not allow their daughters to marry heathens, whereas marrying Catholicised women of both natives and Eurasians produced during the Portuguese era was not recommendable. Although, Balinese women, whose religion, Hinduism, was rather generous for intermarriage, were their reasonable choices, women from highly civilised Japan were quite attractive. In fact, Jan Pieterszoon Coen himself frequently sent letters to Hirado, writing, “We look forward to the arrival of married couples and their children as well as unmarried women from Japan at an appropriate time, Do not forget to transport unmarried Japanese women [from Amboyna and Banda], if possible” [23], etc.

Cornelia, a daughter of Cornelis van Nijenrode

Having read such a history, I remembered a painting that I once saw in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, displayed in the centre of the main hall of the first floor. It was a family portrait in which a Dutch gentleman, his half-Japanese wife and three daughters stood in front of their luxurious house with their servants. At that time I was only impressed by the fact that “among those deportees to Jagatara was such a girl who married a Dutchman and had a rich life”, but later learnt that the painting was a piece entitled ‘Pieter Cnoll and his Family’, painted by Jacob Coeman in 1665, and that the lady was Cornelia, a daughter of Cornelis van Nijenrode who was the Chief Merchant in Hirado (1623–33) and his Japanese wife, Surisio[24]. Cornelia went to Batavia in 1637, two years earlier than Haru, together with her half-sister, Hester. She married Pieter Cnoll, who was to be promoted to Chief Accountant and Port Master of Batavia. Four years after Pieter passed away in 1672, she remarried Joan Bitter, a newcomer, or orang baru in the local words, who came from Holland, and was four years younger than herself.

|

Pieter Cnoll and his Family by Jacob Coeman 1665. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam: Identification code: SK-A-4062. Reproduced by courtesy of the museum, from http://www.rijksmuseum.nl/ |

Unfortunately, their relationship soon deteriorated, as the new husband claimed the proprietorship of Cornelia’s property, which she had amassed with her first husband. In 1687, Cornelia and Joan went to Holland on board different ships to settle the case at the court and Cornelia ended her life presumably in 1692, as written in detail in Butterfly or Mantis? The Life and Times of Cornelia van Nijenrode by Leonard Blusse [25]. Contrary to the naive image in the picture, Cornelia would have been a woman of strong will. In the Japanese translation, the title of the book was changed to The Struggle of Otenba Cornelia. I have learnt that the common Japanese word “otenba” to describe an active and uncontrollable woman was derived from the Dutch word, ontembaar, from a friend of mine in Jakarta who is fluent in Dutch and knows Japanese language a little. Although the second-half of Cornelia’s life was miserable, her life in Batavia before she was bereaved of her first husband was smooth sailing as she herself wrote in her extant “Cornelia’s Jagatara Letter”, in contrast to the life of Haru as was sympathetically written in such a way as “perished as though trees and weeds” and “ended harbouring a grudge” by Yosaburo Takekoshi and Marquis Tokugawa, respectively. With reference to Prof. Iwao's study, it would be better to imagine that Haru also had a happy life in Batavia except that she had no hope to visit her homeland again, as written without prejudice by Tetsushi Masanobu in A Novel: Jagatara O-Haru published in 1996 [26]. In “The Legend of Haru”[27], written by Hiroko Shiraishi and published in 2001, the author assumed that Haru’s life was a happy one and wrote about it by adding her own imagination. I would also imagine that both Haru and Cornelia who were dreaming teenagers when they arrived at Batavia would have submitted to their fates and faced up dauntlessly to their new lives in the new land. In Batavia, Haru at the age of twenty-one married Simons Simonsen, a young man, probably born in Hirado between an Italian sailor who had arrived there by a Portuguese ship and a Japanese mother, who was deported like Haru herself. Although she lost her elder sister, Man, two years earlier and her mother one year later, her married life was smooth, blessed with three sons and four daughters. Her husband once received an order to be transferred to the VOC’s headquarters in Holland, but the couple remained in Batavia as the company accepted their wish to stay there as half-Asians. Then, Simons was promoted up to the Harbour Master of Batavia. Although Haru lost her husband from a disease when she was forty-seven, she lived there surrounded by her children and grandchildren until she died at the age of seventy-two, a long life at that time. Among extant “Jagatara Letters”, there is one piece signed as “Haru, Widow of Simons”, which was written in a plain style, unlike the elegant first letter in Nagasaki Night Tales, and believed to be authentic. It included a large list of presents, such as white cotton cloth, calico and figured satin, which were sent to her ten-odd relatives in Japan, and her requests to have some white cloth dyed in Japan and returned to her, to ship some barrels of Japanese sake, etc., with the money she remitted. This ensures that Haru was quite rich in Batavia.

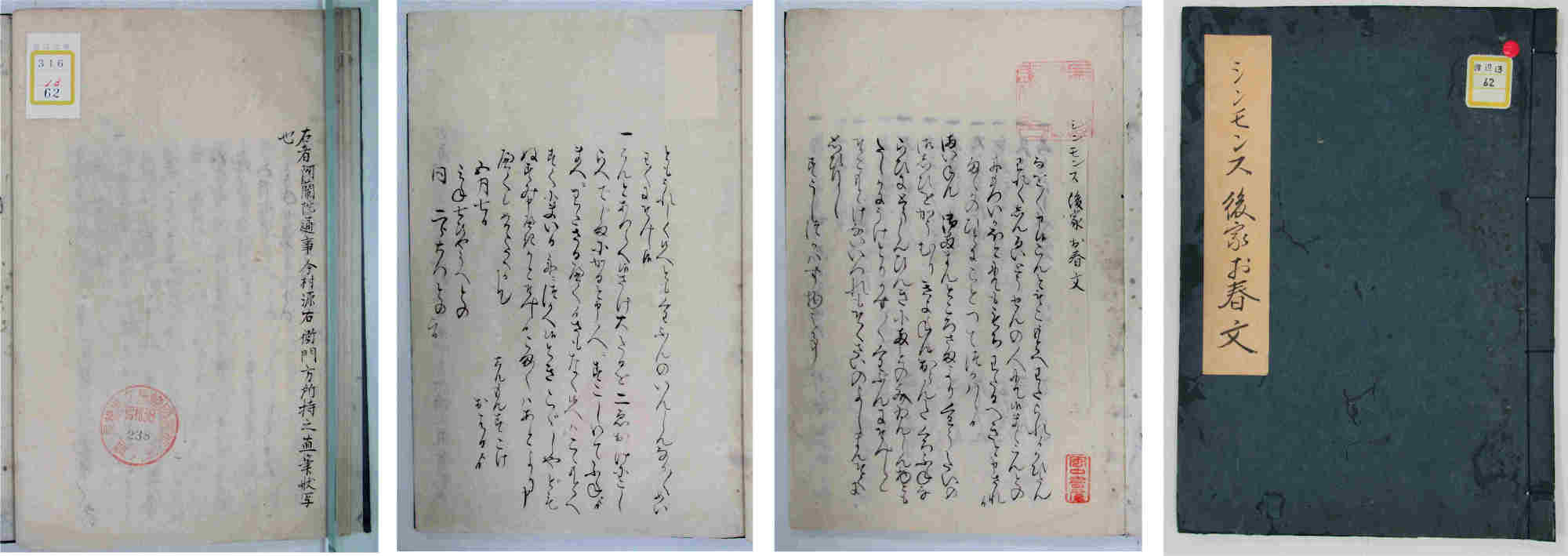

| A letter from Haru, Widow of Simmons.

Copy obtained from Nagasaki History and Culture Museum, by courtesy of the museum. From the right to the left, Cover, Page 1, 11 and 12 (last page). At the end of the text (p.11) it is dated as the 7th May and addressed to Messrs. Shichibei Mine and Jirouyemon Mine. On the last page, it is written that “This is a hand-writing copy held by Gen-yemon Imamura, an interpreter”. Judging from the context, some more paragraphs are supposed to have existed in the original copy before the first page. |

Whilst most Japanese women, including Haru and Cornelia, married Dutchmen, by the latter's preference, the partners of Japanese men were mostly Balinese and Batavian women, save such a rare case as that of Haru’s half-sister, Man (Magdalena), married to Buzayemon Murakami, an influential person among Japanese inhabitants. Thus, pure Japanese stock was rarely reproduced in Batavia and their community gradually deteriorated namely after the “Deportation of the offsprings of Red-hairs” and almost disappeared by the end of the 17th century, as it happened also in Ayutthaya in Siam and Manila in Luzon. [28] , [29]

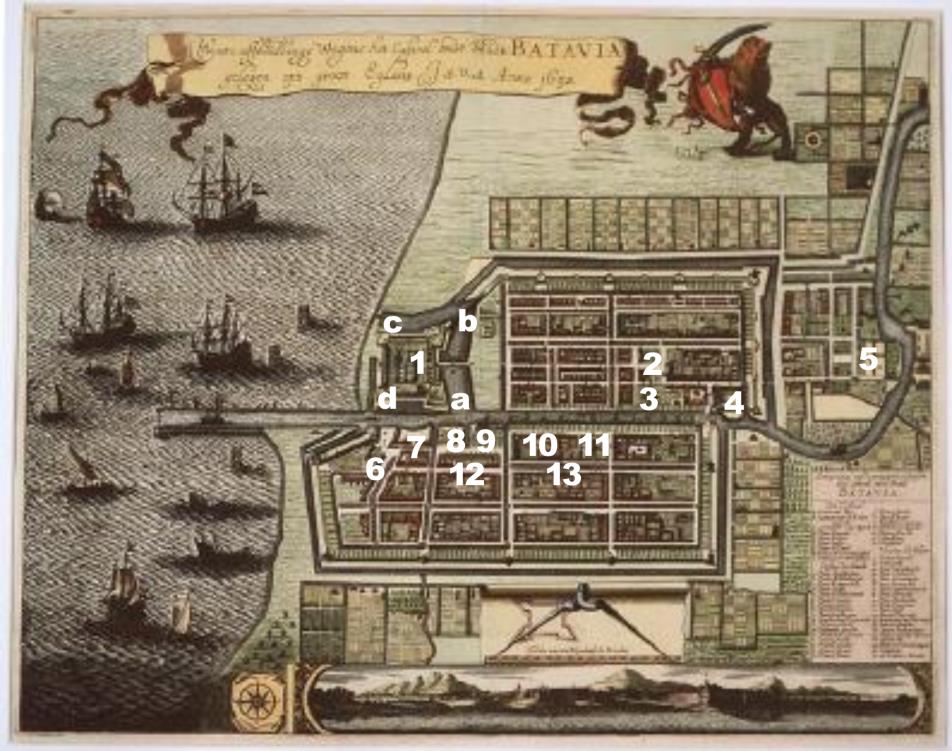

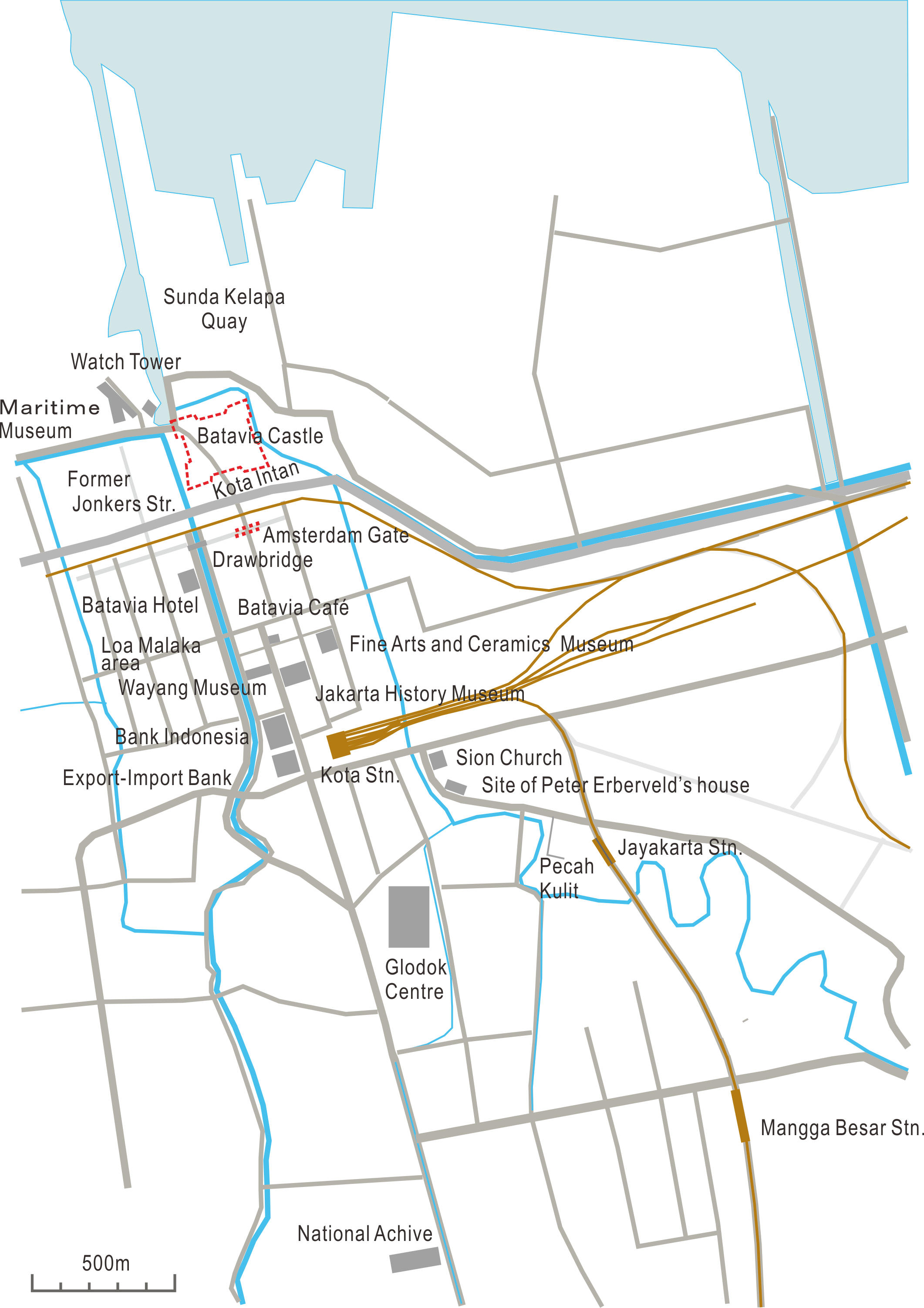

The time when Haru spent her life in Batavia coincided with the period when the town developed. The meandering part of Ciliwung River near its mouth was modified into the straight Kali Besar (lit. Big River) and the city was designed in such a way that canals and roads run lengthwise and crosswise like in towns in Holland. To the south of the fort on the east side of the river were located the Stadthuis (city hall), a church, a hospital and other public buildings, whereas on the west bank were situated shipyards, a fish market, etc. [30]. According to an old document discovered by Prof. Iwao, Haru lived, at least for a certain period, in a housing area to the west of the river. In a picture, ‘Fortress of Batavia (a view from the Kali Besar West)’, painted at that time by Andries Beeckman, it is seen that the urban area was still unfilled, many people gathering in an open market in the shade of palm trees and some officers riding horses on the opposite bank in front of the wall of the castle. People drawn around the market are various, as one can see Europeans, Chinese, Javanese and those of different ethnicities from peripheral islands, and a man who looks like a Japanese is among them. Their statuses and professions are various too. Besides those who are selling and buying goods, there is a married couple with a parasol, Ambonese warriors who are dancing cakalele (war dance), a group of people who are playing sepa raga (indigenous football), etc. Four hundred years having passed, Batavia has grown to be one of the largest modern cities in Asia, being renamed Jakarta after Indonesia’s independence. Prior to picking up some topics from the city’s history, let us visit the area where Haru would have lived.

|

Batavia in c. 1652. Map from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jakarta (estimated to have been drawn by De Jonghe in Amsterdam from some other similar copies). Note the direction, Left points the north. 1: Fort Batavia (a. Diamond, b. Ruby, c. Pearl, d. Sapphire), 2: Stadhuis (City-hall), 3: New Church, 4: Hospital, 5: Governor’s residence, 6. Square, 7. VOC Shipyard, 8: Chinese shipyard, 9: Pasar Ikan (Fish market), 10: Vegetable and Meat Market, 11. Portuguese Church, 12. Jonkers Street (Simons’s house was near by), 13. Roea Malacca (Roa Malaka). The locations have been added with reference to F. de Haan, Oud Batavia (Eerste Deel), G.Kolff & Co., Batavia 1922 and Abdrurrachman Surjomihardjo, Pemekaran Kotas Jakarta/The Growth of Jakarta, Penerbit Djambatan, Jakarta 1977 |

|

Fortress of Batavia, or Batavia Castle, seen from Kali Besar West with Pasar Ikan (fish market), or Vegetable and Meat Market(?), in the foreground, by Andries Beeckman ca.1656–8, held at the Troppenmuseum. Reproduced from http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andries_Beeckman. Another painting with a similar composition is held in Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. |

If one leaves the skyscrapered Jakarta city centre and goes four or five kilometres towards the north to the downtown area called Glodok, where Chinese descendants concentrate, the atmosphere suddenly changes. The scenery in which pavements in front of shops are crowded by people and handcarts, both busily moving back and forth, may remind you of an old Chinese phrase, “shoulders bump and shafts of carts crash”. In the backstreet are shopping centre buildings full of small booths in which all kinds of electronic, computer and machine products and parts are sold. It was the place I frequented during my stay in Bogor to hunt laboratory tools and requirements. The area in the north of Glodok is called Old Batavia or Kota (meaning “city” in the local language). If you walk several hundred metres passing the side of Jakarta Kota railway station and the old building of the former Java Bank (now occupied by Bank Indonesia), you will find an open space, called Taman Fatahillah (lit. Fatahillah Park), i.e. the front yard of the old Stadthuis, now used for the Jakarta History Museum. In the west side of the square is the site of old Kruiskerk (Cross Church), now of use for the Wayang Museum, and Kali Besar runs behind it. The houses on both banks of the river with lovely Dutch facades are well preserved, as if they were somewhere in Holland, and several hundred metres downstream remains an old drawbridge similar to those painted in Vincent van Gogh’s paintings. The former Jonkers Street (now Jalan Ekor Kuning) behind the west bank where Haru’s house had existed gives an atmosphere of typical backstreets, which offers no image of 350 years ago at all.

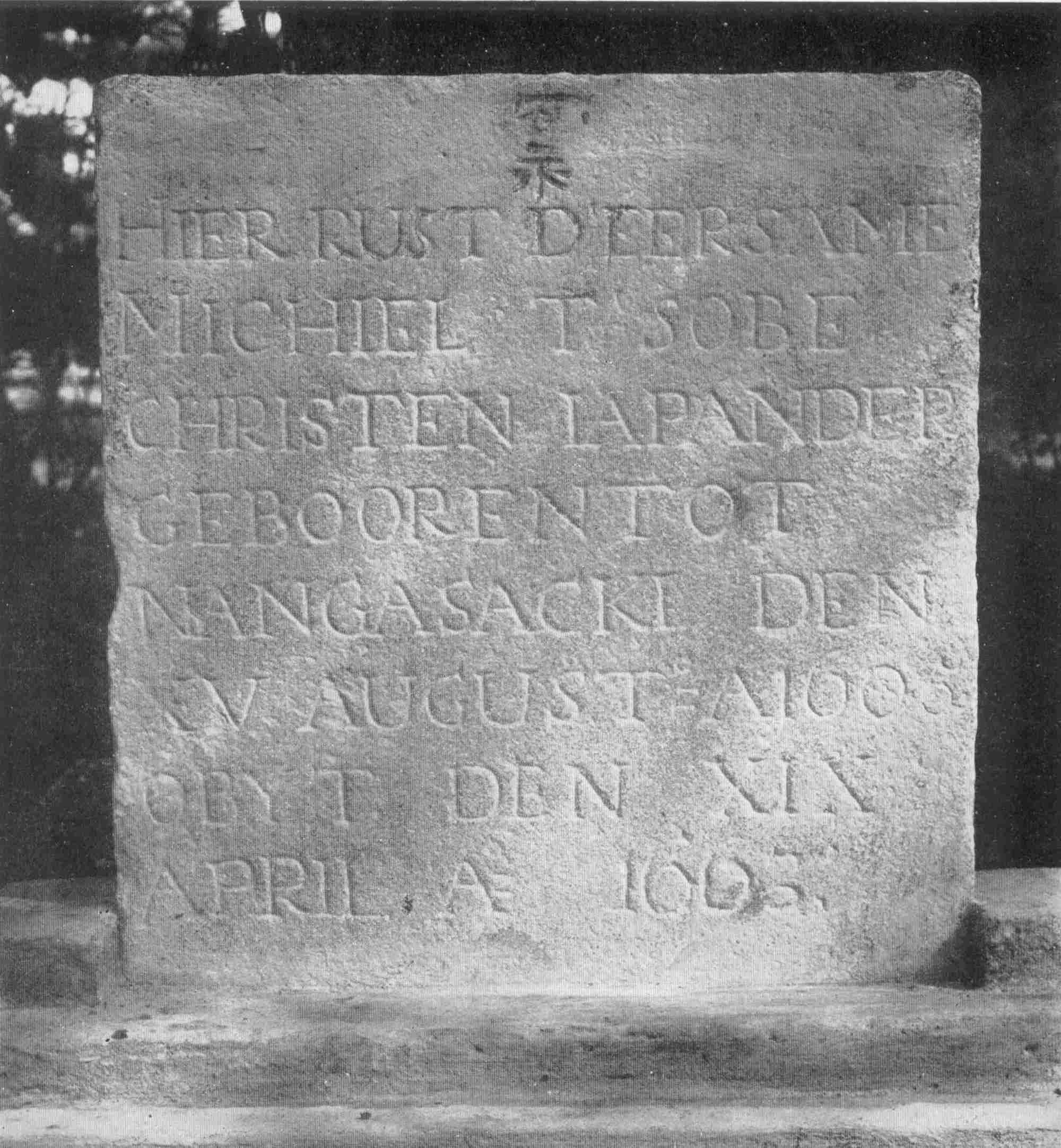

The tombstone of Michiel T’ Sobe

The location of Haru’s house was recorded in the will of a certain Michiel Diaz Sobe. In 1886, before the document was discovered, a tombstone on which a name, Michiel T’ Sobe, was inscribed was found on the pavement of Kali Besar West and aroused interest among historians. Soon, the stone was taken to the Anglican Church in Prapatan by the discoverer, Rev. Armine Francis King, and in 1911 moved to the front yard of the Japanese Consulate [31]. When Marquis Tokugawa visited there in 1921, he wrote [32]:

“There was a grave in front of the Consulate. According to the inscription, it was the tomb of a Japanese man, named Michiel T. Sobe, born in Nagasaki in 1605 [the 10th year of Keichō Era] and died here in 1663 [the 3rd year of Kwanbun Era]. Judging from his age, he was supposed to be one of those who led a resentful life in this land deported from Nagasaki with Oharu, the sender of Jagatara-bumi.”

|

Tombstone of Michiel T’ Sobe. From: F. de Haan, Oud Batavia – Gedenboek uitgegeven Genootschp van Kunsten en wetenschappen naar aanleiding van het driehonderdjarrig bestaan der stad 1919 (Eerste Deel), G.Kolff & Co., Batavia 1922. The text reads: HIER RUST D’EERSAME MICHIEL T’SOBE CHRISTEN JAPANDER GEBOOREN TOT NANGASACKI DEN XV AUGUST °A 1605 OBYT DEN XIX APRIL A° 1663 (See, the English translation in the text.) [33] |

In Oud Batavia, the 300th-anniversary book of Batavia, edited by Frederik de Haan and published in 1925, it was mentioned, “While a samurai had a family name, T’ Sobe must be a given name. Michiel might be a young man who came to Batavia from Nagasaki and married in 1630”, with no further details.

In the will of Michiel Diaz Sobe dated 29 March 1661, it was described:

“Because the testator has no family, he will present, after his death, one third each of all his movable and unmovable properties, stocks, bonds and all other properties, to Sijmon Sijmonsz, Upper Merchant, the Harbour Master and the Licensor of VOC, Michiel Buzayemon and Jan Sukezayemon, both Japanese Christians. This will has been prepared in the house of Meester Sijmonsz, in Jonker Street on the opposite side of the river.”

Sijmon Sijmonsz must be nobody else but the same person as “Simons”, the husband of Haru, and this document suggested that Sobe was a close friend of Haru’s family. Another document to prove that the will was properly executed was also found[34] . When Sobe came to Batavia is unknown. He was alone when he attained his advanced age, although he might have once been married if the man in Oud Batavia corresponded. Whether Sobe was resentful for being in the foreign land or not, he was no doubt a successful person as he left such a significant sum of properties. It is interesting to note that in his text Marquis Tokugawa chose the specific character 惣 for the “so” of Sobe(i), the same character that appeared in the signature in the old documents, among many phonetic alternatives. When I asked the late Mr. Yoshinobu Tokugawa, a grandson of the author, he agreed that the author would have learnt it from Prof. Iwao and applied the specific character when his travelogue was published in 1931, because the author, a biologist and historian, was a person who always pursued perfection.

The tombstone disappeared in the chaotic period after the declaration of the independence of Indonesia. Knowing that chance was scarce, I visited the Museum Taman Prasasti (Stone-inscription Park Museum) in Tanah Abang and the Anglican church accompanied by a friend of mine, Mrs. E., a curator of the National Museum, but nobody knew about the stone itself and no information was obtained. Unsatisfied with it, I prepared a handout on which the photograph of the stone, as well as a message that a reporter would be entitled to receive some reward was printed and distributed around the junk street in Surabaya Street, Jakarta, but no news was heard either.

A portrait of ‘A Japanese Christian who remained in Jakarta after Sakoku [closing of the country of Japan in 1639]’, painted by Andries Beeckman ca. 1656 remains to date. It is one of the ten-odd portraits that are supposed to have been sketched prior to his ‘Fortress of Batavia’ and arranged in it. In the source article it is said that the fact that the man’s religion was Christianity is indicated by his clerical hat [35]. The man with the features of an old pure Japanese face wore a dress that looked similar to a Japanese kimono over his body, a pair of Japanese sandals on his feet and a Japanese sword on his waist, although whether it was his daily wear or special attire requested by the painter is not sure. The man’s name is unknown, but, judging from the fact that he was chosen as a model by the famous painter, he is supposed to have been a certain Japanese inhabitant in Batavia. The year of the work, ca. 1661, was several years later than that of the preparation of Michiel Diaz Sobe’s will. Wasn’t the old man with a solitary appearance Michiel Diaz Sobe himself?

|

A Japanese

Christian who remained in Jakarta after Sakoku, by Andries Beeckman ca.

1656, Reproduced from: Marie-Odettte Scallie, Archipel 54, 1998. The same paper includes 13 more portraits: A European of mixed blood, A Chinese merchant, A Chinese labourer A Chinese artiste, A Chinese in Ming costume, A Malayan, A Javanese, A Mardijker (descendant of free slave), A vegetable seller, A rice-pounding woman, A person of mixed-blood (albino), An Ambonese warrior, An Alfour (definition unknown to the present writer). |

In the area of Pasar Ikan (Fish Market) in the west side of the mouth of Kali Besar, you will see a three-storey brick building. It was a watchtower built in 1839 at a corner of the former VOC shipyard and functioned like a control tower in modern airports. Several old cannons placed at the edge of the yard to point to the sea must have been the provisions to protect the port from dangerous ships, if they approached. From the top floor of the tower, which is now empty, you can see a panorama of Sunda Kelapa, on the quay of which are anchored hundreds of Buginese ships [36], many of them being fully loaded with wood from Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo). Because of the silting of sands carried by Ciliwung River, the port of Sunda Kelapa became unsuitable when large modern vessels emerged in the late 19th century. Then, a new port was constructed five kilometres to the east at Tanjung Priok, designed after the port of Rotterdam. Although it has been a long time since the age of the passenger boat ended, Tanjung Priok is still busy as a major trading port of Java Island, parallel with Tanjung Perak of Surabaya, East Java.

|

A view of Pasar Ikan in the Old Batavia area. In the right-hand side, a part of the old city wall remains in front of an old VOC warehouse, which is now of use as the Maritime Museum. The watchtower of Sunda Kelapa harbour is seen in the distance. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012. |

Close to the watchtower, there remains a VOC shipyard building [37] and several old warehouses. While the former is now of use as a restaurant, one of the latter has been used for the Maritime Museum since 1997. On entering the large two-storey building, which was built in 1652 and continually reformed and extended until the end of the 18th century [38], one may be surprised to see large, wooden pillars and beams sawn from giant teak trees, which could not be found today even in the depths of the jungles. When I visited there for the first time I thought that the building itself had great antique value. Picturing a scene where the shelves in the warehouse were full of nutmeg, pepper, coffee beans, tea and quinine, I imagined how Java was rich in olden days. As I learnt in school, the price of pepper was equivalent to that of silver by weight in 17th-century Europe. Although the collections of the museum, such as the models of old ships and old ship fittings, displayed on both the ground and the first floor, looked outshone by those in the Rotterdam Maritime Museum on the other end of the sea-route where I had once visited, they were enriched recently by adding new pieces, such as a traditional fishing boat of New Guinea, called candik or karere, with a long float (outrigger) devised some three metres apart parallel to the main boat.

|

A VOC shipyard building, now a restaurant, viewed from the top floor of the watchtower. Photographed in March 2014 and presented by courtesy of Mr. T. Hirosawa. The sign on the wall must be new, as it says “VOC-Galangan” in Indonesian (This picture is new in this English edition, not included in the Japanese Edition). |

In front of the Maritime Museum, one may find a fragment of the original city wall, but no trace of the old fort remains on the opposite side of the river. According to old plans, Fort Batavia was a bastion-type construction, adopted in Japan later in 1866 for Goryoukaku in Hakodate, Hokkaido. I have had chances to see the same type of forts, Fort Speelwijk in Bantam (the present-day Banten Lama), West Java, and Fort Rotterdam in Macassar, Sulawesi (Celebes). While only stonework of bastions remained in the former, the latter was almost perfectly preserved, including its whitewashed stone-made gate, barracks with red-tile roofs and other facilities, save that what was flying on the pole was not the tricolour Dutch flag but the bicolour Indonesian flag. Imagining the old-day soldiers on the people in the court, I thought over the scene of old Batavia Castle. Although small in scale, the Benteng Vredeburg (Fort Vredeburg) found not far from the Palace of Yogyakarta, on Malioboro Street, was the same bastion type. Although a part of the internal buildings are of use as a museum to commemorate Indonesia’s independence, no atmosphere of a facility for war is sensed now, as various stalls in the courtyard are crowded by people every night.

“Diamond”, one of the four bastions of the Batavia Castle (i.e. Diamond, Pearl, Sapphire and Ruby), retains its name in Jalan Intan or Kota Intan ( lit. Diamond Street or Diamond Town, respectively). The yard of the former fort was flattened for certain sightseeing facilities and the watchtower of the harbour was seen in the north. Having heard from a local gentleman who had a small house there until 1995 that an entrance of an underground vault or a trench had remained until 1997, I thought I was fifteen years too late to visit there.

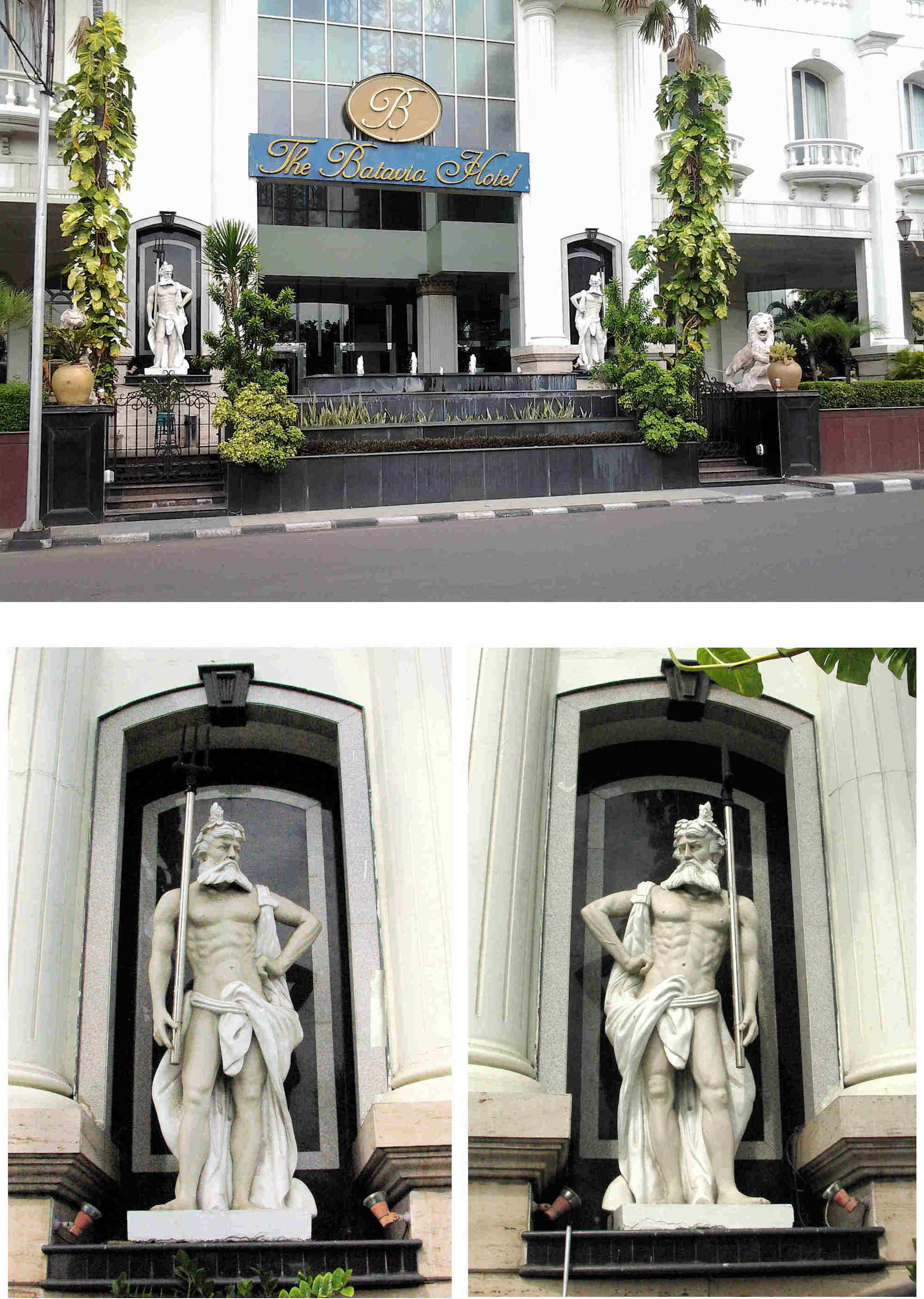

The only modern building that stands around Kali Besar is the Batavia Hotel, Jalan Kali Besar Barat 44–6, opened in 1995. I was charmed by its front design with a pair of white marble statues placed in the alcoves of both front pillars, as it looked a little similar to that of the Amsterdam Gate (De Amsterdamse Poort), which had once existed to the south of Batavia Castle. Although the statues were symmetrical with each other and dissimilar to those of Mars and Minerva [39] in the Amsterdam Gate, which I had seen in old pictures, I supposed they were modelled after some Roman deities. According to my friend in Jakarta who made an enquiry for me, the present manager of the hotel had no knowledge about their origin. Having referred to books [40], I became convinced that the model was none other than Janus, the Roman Deity of doors and the beginning of things, from which the word “January” was derived. While Janus was generally depicted as a figure with two faces [40a], the anonymous artist who worked for the Batavia Hotel had symmetrically duplicated the body to be separate statues. Just for reference, the two statues of the Amsterdam Gate were removed and probably destroyed in 1942–5 by a Japanese occupation army and the gate itself was demolished in 1950 by the Indonesian government for the reason that it was an obstacle for transportation.

|

Top: Front view of the Batavia Hotel. Photographed by Ir. Arief Budhiono, a friend of M. Iguchi, March 2012. Bottom: The statues of Janus. Photographed by M. Iguchi, February 2012. |

|

The Amsterdam Gate of Batavia Castle (demolished in 1950). Photographed by Marquis Yoshichika Tokugawa in the 1920s. Reproduced by courtesy of the Owari-Tokugawa Family. |

|

Batavia City Hall and the Holland Church by Johannes Rach 1770. Reproduced from: Max de Bruijn and Bas Kist (text), Johannes Rach 1720–83 Artist in Indonesia and Asia, The National Library of Indonesia/The Rijksmuseum Amsterdam 2001. The building in the centre is apparently the “old” city hall, which was replaced with the “new” city hall in 1707–10, whilst the New Holland Church on the right-hand side was built in 1732. The reason why the “old” city hall was drawn in this picture is unknown to the present writer. |

Time passed and when Europe was under the control of Napoleon Bonaparte, the status of Holland changed from the United Netherlands to the Batavia Republic in 1795 and to Holland Kingdom crowned by Louis Napoleon in 1806, and the country was finally merged into France in 1810. General Herman Willem Daendels, a votary of Napoleon who went over to the French side, was appointed the governor-general of the East Indies to defend the territory from the anticipated attack by the English, and arrived in Java in 1806. The first task he performed was the reforming of Batavia. By abandoning the fort near the port, he constructed the new town, Weltevreden, eight kilometres to the north, placing a parade ground there, and prepared a defence line in Meester Cornelis (the present-day Jatinegara), another twenty kilometres to the south, by utilising the stone and other materials that had been used for the old fort. The parade ground, formerly called Koningsplein, was renamed Medan Merdeka (lit. Independence Square) after the independence of Indonesia and the Independence Tower (locally called Monumen Nasional or Monas for short) was placed in its middle. The open area still functions for the ventilation of the crowded central area of Jakarta.

Daendels also constructed a fortified city, 180 kilometres east by southeast of Batavia, in the basin of the present-day Bandung surrounded by mountains, the date of breaking ground 10th May 1810 being adopted today as the birthday of the City of Bandung. These were not all of Daendels’ preparations. In 1808, he ordered the construction of an 800-kilometre long post road, De Groote Postweg (locally, Jalan Pos Raya) across Java Island from Anyer in the west end to Panarukan in the east end, and completed it within one year at the expense of 20,000 lives. Despite his efforts, Daendels was relieved from his post in May 1811, as his administration did not run smoothly because of his fierce personality, and it was General Jan Willem Janssens who faced, and surrendered, to a British Army, which actually came to occupy Java three months later, led by Lord Minto. When the restoration of Java and its dependencies to the Netherlands was agreed in the Peace of Vienna in 1815 [41], King Willem the First decided to govern the East Indies by the hand of the government, not by entrusting the administration to such a company as the former VOC. Thus, Batavia entered into a new era. The VOC itself officially became bankrupt in 1799, but the company’s balance had already slipped after the middle of the 18th century due to the internal conflicts and the payment of excess dividends demanded by the shareholders [42].

Let us visit the old Stadthuis, the present-day Jakarta History Museum. If you enter the two-storey building of some fifty metres wide with a dome in the middle of the roof, you will notice that the building is constructed with gigantic teak pillars and beams. On the right-hand wall of the corridor passing from the entrance to the backyard is a large black plate on which is inscribed in gold in Dutch [43]:

|

This Government House was started to be built on the site of the old building by the Governor-General JOAN VAN HOORN on 25th January 1707AD. It was completed on 10th January 1710AD under the Governor-General ABRAHAM VAN RIEBEECK. |

The original building is said to have been designed after the city hall of Amsterdam and, according to an old picture, it seems to have been a little smaller than the present building. Since the construction had been finished in 1637, three years earlier than the arrival of Haru, it must have been there that she submitted her marriage registration form and her wills. In the interior of the present building are housed various relics related to Jakarta, such as a large bookshelf with glass doors placed in the large main hall on the upper floor along with various furniture. Among many paintings displayed on the walls, a portrait of Jan Pieterszoon Coen is most conspicuous. Although there are some complex feelings among Indonesians for the person who established the Dutch presence in the East Indies, it is undeniable that he was one of the greatest men who brought prosperity to both the modern Holland and the East Indies. To myself, it was impressive that the wife of a Dutch friend, a daughter from a noble family, stood still, gazing at the picture with respectful eyes.

|

Top: City Hall (Stadthuis) built in 1627. Replaced with a new building in 1707–10, which remains to date. Bottom-Left: Portuguese State Church (Stadskerk). Burnt in 1808. Bottom-Right: Portuguese Suburban Church (Buitenkerk). Remains to date as Sion Church. Reproduced from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Algr001disp04ill55.gif |

A tale of Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the founder of Batavia

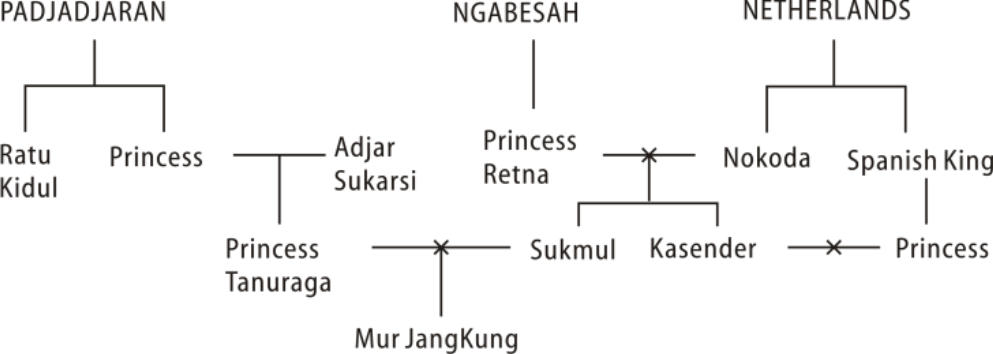

Although Coen was a pure Dutchman born in Hoorn in 1587, there is an interesting tradition. According to The Book of Baron Sakhender ( Serat Baron Sakhender), written in the 18th century in Solo in the Javanese language in the form of a long poem, Coen was a man called Mur Jangkung born of a Pajajaran Princess, Tanuraga, and Baron Sukmul, a brother of Sakhender (Alexander) from Spain. Although accessing the original copy of its Dutch translation was difficult and citations in many articles were fragmental and ambiguous, a book [44] in which the story was explained in detail in English was available. The story of Mur Jangkung was written in the second part of the book.

“Probably in the middle of the 16th century when the Islamic power led by the Pangeran[45] of Jayakarta encroached on the territory of Pajajaran Kingdom, one of the princesses fled to a mountain, where she became pregnant by the Ajar Sukarsi[46] and gave birth to a daughter of surprising beauty, named Tanuraga. The Pangeran of Jayakarta abducted Tanuraga but could not sleep with her because flames emitted out of her genitalia. She was therefore deported to a small island. Pulau Putri [lit. Princess Island] in the Bay of Jakarta. The Sultans of Cirebon and Mataram in turn took her for themselves but neither of them was successful to possess her either, for the same reason. She was sent back to the island and lived there in sorrow.

“There, Sukmul came from Spain on board a trading ship and bought her for three pieces of cannons[47] and took her home. Sukmul and Tanuraga married and a son born between them was named Mur Jangkung. When Mur Jangkung grew up to be a famous warrior and heard about his origin, he decided to take revenge upon the Islamic princes who had disgraced his mother and ruined her country, Pajajaran, and sailed to Java with a fleet of fifteen warships. Although Mur Jangkung was well received not only by Dutch settlers but also the Pangeran of Jayakarta and mixed with the local people with Malay which he had learnt from his mother, he was all the while making military preparation for his revenge. When a cannon ball accidentally fell in the ground of kraton [palace] during his practice, the Pangeran told him in anger to leave Jayakarta, but he begged a pardon saying that he would suffer a great commercial loss. It was the Pangeran himself who, in accordance with the will of God, moved to Gunung Sari [within the boundary of the present-day Jakarta] to get away from the Dutch and their cannon. Mur Jangkung was pleased at this and built a castle called Kuta Tai. The Dutch attacked the Pangeran, but the war situation became deadlocked, as the Pangeran’s younger brother, Purbaja, a warrior with a supernatural power, joined the enemy. Sukmul who heard of this in Spain came to Java and gave advice to his son. When coins were discharged, instead of cannon balls, towards Gunung Sari, the soldiers of Jayakarta ran out to pick up the money. Then, real cannon balls were shot to fell them down. By the will of God, filled with fear, the Pangeran of Jakarta retreated to the mountains to the south of Jakarta, but soon his troops left him. He became a mere rebel, practising asceticism with local people, with no hope to recover any lands. In great sorrow, he thought that he had once sold the daughter of Sukarsi and the Princess of Pajajaran was his error and, asking himself within his heart, ‘What is the will of God for my course of life?’, deplored that he would be punished by Sultan Agung of Mataram and die. The Dutchmen in Batavia grew even more, setting forth their designs to create a city surrounded by water. The River Ciliwung was incorporated in the city.”

In the above story, it is said that Mur Jangkung came not from Holland but Spain. It was because in the first part of the long poem in which the family line of Sukmul and the situation in Europe were described, Spain was placed under the control of Holland. The first governor of Holland was Nakoda (lit. Captain) who was born, cut out of the womb of his mother. Although he was an orphan, he became famous in battle and rich as a merchant, and took twelve daughters of twelve kings as wives. These wives were infertile, but when Nakoda went to the mountains and implored a hermit, Mintuna, for help, eleven of them became pregnant and gave birth to eleven sons, who all later became the board members of the company (VOC). The wife who did not have a baby at that time was Sang Retna (Princess Retna) of Ngabesah. She had been treated coldly by her husband and put to live apart in the cooking-place, but, after fourteen years, produced a sea-shell from which twin sons, Sukmul and Sakhender, appeared. After fourteen years, Sakhender was called by Mintuna to visit the latter’s hermitage. He was almost eaten by the hermit but managed to kill him. Sakhender went to Spain and, being entrusted by the king as a distinguished warrior, married the princess. Then, he won an important war [48]. The fact that the king of Spain was a long-separated brother of Nakoda was revealed and the throne was given to Sakhender. Although Spain prospered under the rule of Sakhender, after a while, Sakhender left Spain for Java where commerce was also excellent, handing over the throne to Sukmul. In Java, Sakhender became a vassal of the Sultan of Mataram.

The adventure of Sakhender was supported by the magical power of a demon king, Singgunkara, as well as several retainers, including Kaseber and Suhuruman, twin brothers born almost simultaneously from a mango-stone produced by his mother’s maid, a horse called Sumbrani, who was said to be a brother of Sakhender, and a bird called Garuda, who was said to be a brother of Kaseber. Indeed the story reminds us of some Arabian Nights.

A family tree such as below can be derived from the Book of Sakhender.

According to this genealogy [49], an assumption is possible that Mur Jangkung (or Jan Pieterszoon Coen) who had the blood of Pajajaran returned to his mother’s country rather than conquering Jayakarta. The time when this book was written was already 200 years since the Javanese had first encountered the Dutch and the former should have acquainted with right knowledge about European history. Why was such an unrealistic story created? The prime answer can be, “It was fiction.” As to the reason why the author wrote such an allegory that might justify the invasion of foreigners, there is an interpretation that it was not a matter of concern for Javanese (in Central and East Java), because the land of Sunda, or the west part of Java Island, was regarded to be a foreign land. [50] One could alternatively say that the idea of self-determination only evolved after the First World War as a political principle, proposed by the then American president, Woodrow Wilson, in the 20,000-year-long human history.

|

Left: A portrait of Jan Pieterszoon Coen. Reproduced from: http://commons.wikimedia.org/ Right: Wayang Golek Puppet of Mur Jangkung (Jan Coen). Reproduced from: http://indonesia.elga.net.id/wayang/ |

Lingering charm of old Dutch churches

In the Wayang Museum located on the left-hand side (west side) of the Stadthuis’ front yard (Taman Fatahillah) is a large collection of puppets for wayang golek as well as wayang kulit, not only for playing classic Mahabharata and Ramayana but also for semi-modern titles. Although the puppet of Mur Jangkung, which I saw in a picture, was unfortunately not found, there was an interesting pair of puppets, Jan Pieterszoon Coen in his military uniform and Prabu Siliwangi, the king of the Pajajaran Kingdom in his traditional costume, standing face to face. Historically, they should not have had a chance to meet with each other because the kingdom had perished forty years earlier than the arrival of Coen. Presumably, there might have been a fictional story in which the two prominent figures had met with each other, but the curator of the museum was not sure of it.

|

Wayang Golek Puppets. King Siliwangi (left) and J. P. Coen (right). Wayang Museum, photographed by M. Iguchi 2007. |

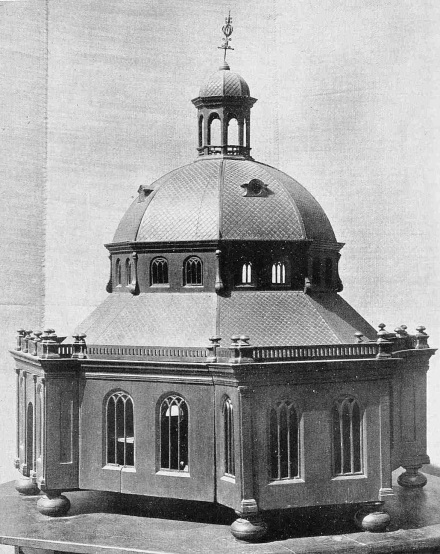

In the same building, what looked strange to me was a number of tombstones placed like panels on the walls of the corridor on the ground floor, on the largest one of which was the inscription of Jan Pieterszoon Coen’s legend. As mentioned earlier, this was the place where Kruiskerk (Cross Church, alias Hollandsche Kerk) was originally built in 1632–40. A picture drawn in the 1680s shows many faithfuls gathering around the church. They were, needless to say, the Reformers who followed Calvinism, the same sect that drove the independence of the Netherlands from Spain [51]. Haru, who was a Catholic, when first baptised in Nagasaki would have converted to the Reformed faith in Batavia [52], attended this church every Sunday and celebrated her wedding there. As to the wedding party of the old days, I could find only one picture painted 100 years later. The party style in which invited guests were going round in front of the bride and bridegroom standing in the front of a hall was probably similar at the time of Haru. The Dutch party style was followed up until today as I saw in the wedding parties of my acquaintances that included a niece of the Soekarno family, and sons and daughters of my friends and my young colleagues, without respect to the class or the level of family

|

Wedding in Batavia by Jan Brandes (around 1778–85). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam: Identification Code: NG-369. Reproduced by courtesy of the museum from the museum’s website. |

|

The model of the Holland Church (now displayed in the Jakarta History Museum). Reproduced from: F. de Haan, Oud Batavia (Eerste Deel), G.Kolff & Co., Batavia 1922. |

|

De Kruiskerk (The Cross Church), by Johan Nieuhoff 1682. Reproduced from http://www.onderwijsbeeldbank.geheugenvannederland.nl/ |

Judging from the social status of Simons Simonsen, Haru’s husband, I assumed that they were also buried in the same churchyard, but only tombstones of several governor-general class people remained in the court of the old church. Although many others are said to have been removed to the graveyard in Tanah Abang, the present-day Museum Taman Prasasti, I found no tombstone of Haru’s time. On the site of the Cross Church, the Calvinist’s Reformed Church (Gereformeerde Kerk or Nieuwe Hollandsche Kerk) was built in 1736, but it was closed in 1808. The religious centre of the same denomination was transferred to the Willemskerk (now Gereja Immanuel or Immanuel Church) built in 1835–9 in Weltevreden, the new city centre.

|

Immanuel Church, Medan Merdeka Timur, Jakarta (The former Willemskerk, Weltevreden, Batavia). Photograph taken by M. Iguchi, December 2000. |

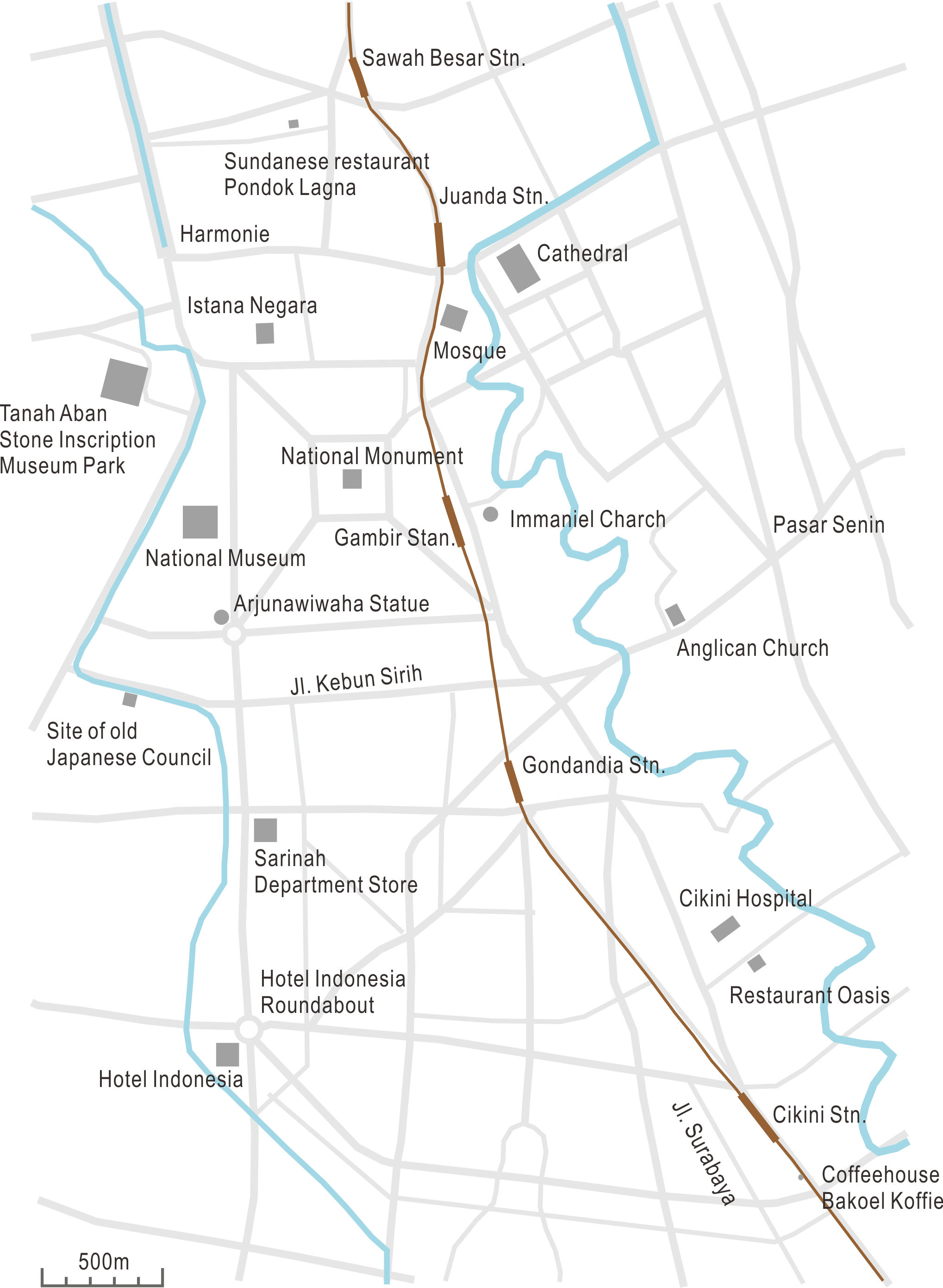

| Jakarta Map |

| North Jakarta (Old Batavia Area). Roads, railways and waters drawn on Google Earth. |

| Central Jakarta. Roads, railways and waters drawn on Google Earth. |

[1] The English verse is a trial translation by the present author. Jagatara is the corrupted form of Jayakarta (the present-day Jakarta) in Japanese. It was corrupted in Europe as Jaccatra ( See text in p.35). “O-“ is a prefix for the given name of women commonly used in olden-day Japan, but not today.

[2] A small artificial island of only 1.31 hectares in Nagasaki, which was furnished for the Dutch to hold their trading post from 1641 to 1859, after the expulsion of the Portuguese in 1639.

[3] Yosaburo Takekoshi, A book of southern countries, Niyusha 1910 (竹越與三郎「南國記」, 二酉社 1910).

[4] Marquis Tokugawa (translated by M. Iguchi), Journeys to Java, ITB Press, Bandung 2004/Marquis Tokugawa (diterjemahkan oleh Ririn Anggraeni dan Apriyanti Isanasari), Perdjalanan Moenoedjoe Jawa, Penerbit ITB 2006 (徳川義親 「じゃがたら紀行」, 郷土出版社 1931 (十字屋書店 1943, 中公文庫1975).

[5] Kabitan, a corrupted form of the Portuguese word, Capitão, denoted a chief of a foreign trading house, originated during the Portuguese Era in Japan (1543–1639). The word was applied for chief Dutch traders (first arrived in 1600) instead of the Dutch word, Opperhoofd.

[6] Seikyu Nishikawa (Ed.), Nagasaki Night Tales, Ryushiken, Kyoto 1720 [In: S. Mishima (Ed.),Nanban-Kibun Cho, Chobunkaku, 1929; Nyoken Nishikawa, Chonin-bukuro, Hyakusho-bukuro, Nagasaaki Night Tales, Iwanami Paperback 1942 (西川正休 (編), 「長崎夜話艸」, 柳枝軒, 京都 1720 [In: 三島才二編「南蠻稀聞帳」, 潮文閣 1929; 西川如見「町人嚢・百姓嚢・長崎夜話草」, 岩波文庫 1942]). “Seikyu” was the nom de plume of Nyoken Nishikawa.

[7] Nyoken Nishikawa, Chonin-bukuro, Hyakusho-bukuro, Nagasaaki Night Tales, Iwanami Paterback 1942 (西川如見「町人嚢・百姓嚢・長崎夜話草」, 岩波文庫 1942). Red-hairs (Koumou) denoted Dutchmen and occasionally Englishmen, while the Portuguese and Spanish were called Southern Barbarians (Nanban).

[8] Elegant or poetic name of Japan.

[9] Yosaburo Takekoshi, Jisseikatsu, No.2, Nov. 1916 (竹越與三郎, 「實生活」 No.2, Nov. 1916). Hakuseki Arai in this citation was a distinguished scholar and bureaucrat in the mid-Edo Period. He interrogated Giovanni Battista Sidotti, an Italian priest who came to Japan against the Christianity Prohibition Edict and, based upon the knowledge acquired from Sidotti, authored Seiyo Kibun (An Oral Account on the West) in 1715. Mr. Koga (Jūjirou Koga) was a devoted scholar of Nagasaki-ology who published The history of occidental studies in Nagasaki I, II (長崎洋学史, 上, 下), 1969, Nagasaaki Bunken-sha, and other books.

[10] Seiichi Iwao, A sequel to: The study on the Nangyang Japanese town, Iwanami-shoten 1987 (岩生成一「続・南洋日本町の研究」, 岩波書店 1987).

[11] Madoka Kanai, A study on the history of Japan– Holland relationship, Shibunkaku 1986 (金井圓「日蘭交渉史の研究」, 思文閣 1986).

[12] Kaoru Fujishiro, Chronological Table of Nagasaki History, (藤城かおる「長崎年表」) , http://f-makuramoto.com/01-nenpyo/.

[13] “1614: Destruction of 11 Kirishitan temples” was recorded in Chikuun Uchihashi (Ed.), Nagasaki Nenreki Ryaumenn-kagami (長崎年歴兩面鏡), 1828. A copy of the very rare chronological table was presented by courtesy of the Library of Kagawa University.

[14] Built in 1637 and put in service 1638–57. Load capacity 1,050 ton, Crew 300. http://www.vocsite.nl/schepen/detail.html?id=11501.

[15] Fell in 1662 attacked by Ch’eng-koeng (See text in p.31). Masaharu Shingu, A Samurai of Zeelandia, Shin-jinbutsuouraisha 1989 (新宮正春「ゼーランジャ城の侍」, 新人物往来社 1989).

[16] Madoka Kanai (Footnote 11).

[17] Chinese text:

加留巴[Kelapa], 下港[Bantam]屬國也, 半日程可到。

Xie Zhang, Accounts on Eastern and Western Countries Vol. 3, 1617

(張燮 「東西洋考 卷三 西洋列國考 巻三」 1617),

http://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=en&res=87006.

[18] The date 22 June is defined as the municipality day of present-day Jakarta. Some historians are not agreeable, as in a newspaper article, Alwi Shahab, “Jakarta anniversary date must be changed: Historian”, The Jakarta Post (23 June 2004. http://www.thejakartapost.com /news/2004/06/23/jakarta-anniversary-date-must-be-changed-historian.html.

[19] Seiichi Iwao, Licensed ships and Japanese town, Shibundou 1962 (岩生成一「朱印船と日本町」, 至文堂 1962). Famous among them was Nagamasa Yamada (1590–1630) who became the king's guard of Ayutthaya.

[20] Madoka Kanai (Footnote 11).

[21] E.g. Michael Cooper, They Came to Japan: An Anthology of European Reports on Japan, 1543–1640 , University of California Press 1965.

[22] C. R. Boxer, The Dutch Seaborne Empire 1600– 1800, Penguin Books–Hutchinson, London 1990.

[23] Madoka Kanai (Footnote 11).

[24] K. Zandvliet, et al., The Dutch Encounter with Asia 1600–1950, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam – Waanders Publisher, Zwolle 2003, etc.

[25] Leonard Blussé, Strange Company: Chinese Settlers, Mestizo Women and Dutch in VOC Batavia (KITLV Verhandelingen Ser No, 122) , Foris, Utrecht 1988/ Japanese translation of “VIII Butterfly or Mantis? The Life and Times of Cornelia van Nijenroode” by Fukuya Kurihara: Leonard Blussé, The Battle of Otemba Cornelia, Heibonsha, 1998 (レオナルド・ブリュッセイ (栗原福也訳)「おてんばコルネリアの闘い」, 平凡社 1998).

[26] Tetsusi Masanobu, Nobel-Jagatara Oharu, San-ichi-shobo 1996 (正延哲士「小説じゃがたらお春」, 三一書房 1996).

[27] Hiroko Shiraishi, Information of Jagatara O-Haru, Bensei-shuppan 2001 (白石広子「じゃがたらお春の消息」, 勉誠出版 2001).

[28] Madoka Kanai (Footnote 11).

[29] Masahiko Wada, Southeast Asia in the Modern Age, University of Air 1991 (和田正彦「近現代の東南アジア」, 放送大学教育振興会 1991).

[30] Abdrurrachman Surjomihardjo, Pemekaran Kota Jakarta/The Growth of Jakarta, Penerbit Djambatan, Jakarta 1977. Ciliwung River was meandering in a map of 1627, but was straightened in the map of 1635.

[31] F. de Haan, Oud Batavia – Gedenboek uitgegeven Genootschp van Kunsten en wetenschappen naar aanleiding van het driehonderdjarrig bestaan der stad 1919 (Eerste Deel) , G. Kolff & Co., Batavia 1922. The original report is found in: Rev. A. F. King, “A gravestone in Batavia to the memory of a Japanese Christian of the seventeenth century”, Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan Vol. XVII, Hakubunsha, Tokyo 1889, pp.79–101 (Google Books).

[32] Marquis Tokugawa (Footnote 4).

[33] A rubbing of the inscription exists in the National Museum of Japanese History, Sakura, Chiba, Japan.

[34] Seiichi Iwao (footnote 10).

[35] Marie-Odette Scalliet, “Une curiosité oubliée: le Livre de dessins faits dans un voyage aux Indes par un voyageur hollandais du marquis de Paulmy”, Archipel 54, 1998.

[36] Bugis is an ethnic group originally from Selawesi (Celebes). They were seafarers and, according to tradition, those who went to Madagascar and settled there in the prehistoric time were the Buginese.

[37] The Jakarta Post, “Ex-Dutch shipyard now trendy cafes”, The Jakarta Post (16 September 2000 ), http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2000/09/16/exdutch-shipyard-now-trendy-cafes.html

[39] Mars was the Roman god of war and agriculture, while Minerva was the goddess of poetry, medicine, wisdom, commerce and arts. They correspond to Ares and Athena, respectively, of Greek mythology.

[40] C. Scott Littleton, Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology, Vol. 6, Marshall Cavendish, 2005; Christopher Irving, A Catechism of Mythology: Being a Compendious History of the Heathen Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes (1822) , Kissinger Publishing 2010.

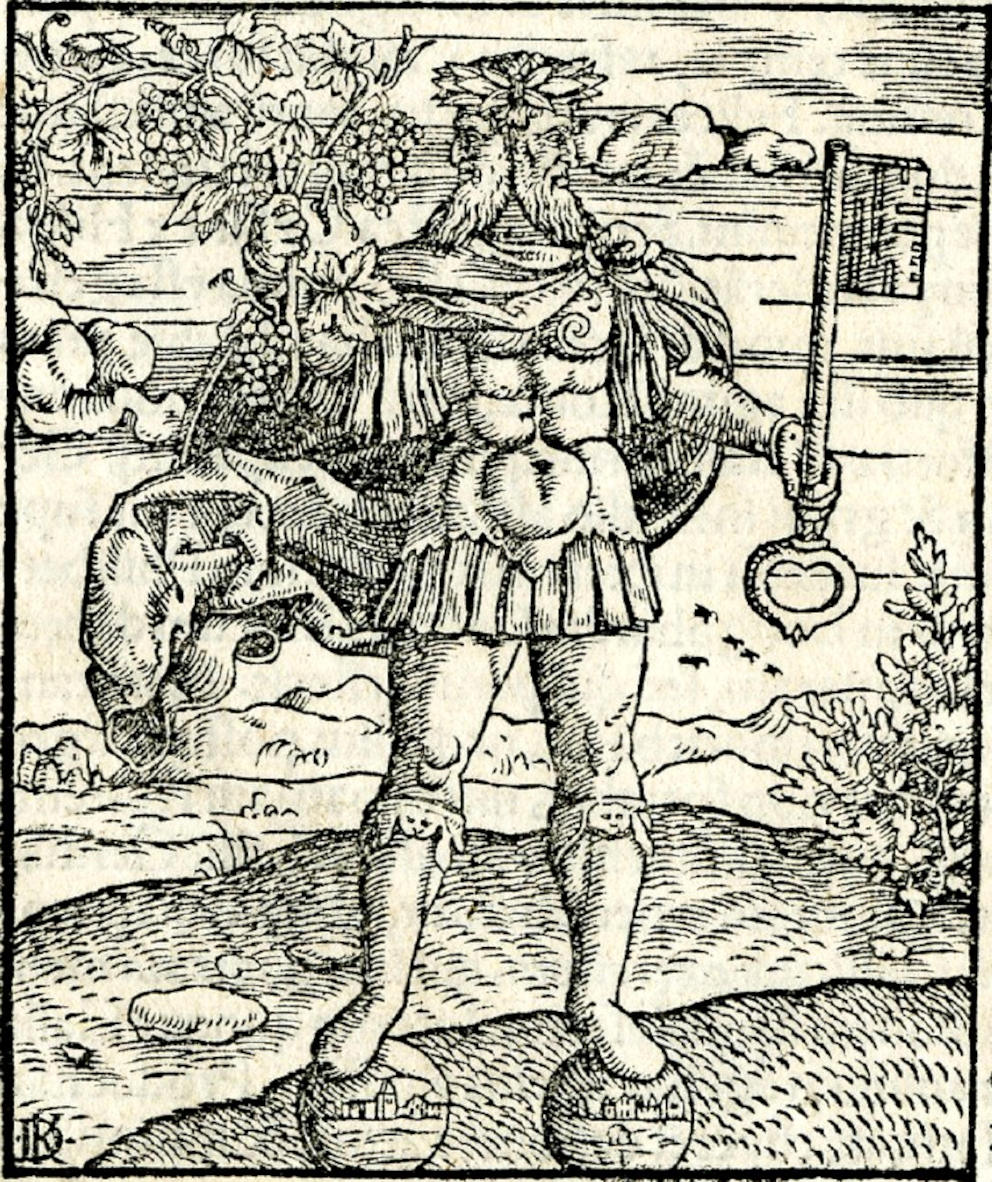

[40a] An example of Janus in: Sebastian Münster, Cosmographia, Heinrich Petri, Basel 1550 (Duplicated from: Wikimedia commons).

[41] The Cape Colony and Ceylon occupied by the British were not returned. The South Netherlands returned became independent as Belgium Kingdom in 1830.

[42] Madoka Kanai, Modern Japan and Holland, University of Air 1993 (金井圓 「近世日本とオランダ」, 放送大学 1993); Kozo Shinano, A history of the Dutch East-India company, Doubunkan-shuppan 1988 (科野孝蔵「オランダ東インド会社の歴史」, 同文館出版 1988), etc.

[43] The Dutch text: “Dit Stad-huis is na het af-breeken van het oude begonnen den 25sten Januari A° 1707 onder de Regeeringe van den Heere Gouverneur Generael JOAN van HOORN” – “En vol-bouwt onder de Regeeringe van den Heere Gouverneur Generael ABRAHAM van RIEBEECK, den 10den July A° 1710”.

[44] M. C. Ricklefs, Jogjakarta under Sultan Mangkubumi 1749– 1792: A History of the Division of Java, Oxford University Press, London 1974.

[45] Pangeran=Prince or lord.

[46] A name, “Ajar Sukaresi”, appears in “Ciung Wanara”, one of the Sundanese traditional poems called Pantun Sunda, as the holy name of King Sang Permana Kusumah (Ciung Wanara’s father) after he became a hermit (See Chapter 4). The spelling is very similar, but whether he was the same person as “Ajar Sukarsi” is unknown to the present author.

[47] Guntur Geni, Ki Pamuk and Njai Setomi. They were transferred to Mataram (Solo), Banten and Cirebon, respectively, and became their regalia.

[48] The enemy was somehow Ngabesah, the grandfather of Sukmul himself, who demanded a princess of Spain, allied with England, France, China, etc. In one speculation, Ngabesah was Abyssinia (Ethiopia).

[49] Ratu Kidul, the descendant of Pajajaran on the left-hand side of the family tree, legendary Queen of the South Sea, has no bearing on the Book of Sakhender. Among various versions, a tradition said, “Dewi Srengenge, a daughter of Mundinglaya Wangi [Siliwangi] was expelled from the palace, when she suffered from a skin disease by the black magic of a witch employed by Dewi Mutiara, the second consort of the king, who had wished her son to be the heir. When Dewi Srengenge reached the southern coast [on the Indian Ocean] and bathed in the sea-water, her disease was healed and an exceeding beauty was bestowed. At the same time, she obtained a supernatural power and became Ratu Roro Kidul, or the Queen of the Southern Sea” (Argo Wikanjati, Kumpulan Kisah Nyata Hantu di 13 Kota, Penerbit Narasi 2010). According to Babad Tanah Jawi, compiled in 18 th-century Java, Panembahan Senopati had exchanged marriage vows with Ratu Kidul and obtained power, and the same relation persisted with the successive kings of Mataram (Nancy K. Florida, Indonesia, No. 53, Apr. 1992 (pp. 20–32), published by: Southeast Asia Program Publications at Cornell University).

[50] E. g. Anthony Reid, “Early Southeast Asian categorization of Europeans”, in S. B. Schwartz (Ed.), Implicit Understandings, Cambridge University Press 1994.

[51] The Eighty Years War (1568–1648). The seven northern provinces were essentially independent before the turn of the century.

[52] The VOC was instructed in orders, dated 1622, to “uphold the religion of the state”, “maintain the sanctity of the church”, and to “destroy all false religions and worship of idols, fight against the anti-Christ, and glorify the kingdom of Jesus”. (James J. Fox (Ed.), Indonesian Heritage Vol. 9: Religion and Ritual, Periplus, Singapore 1998.) They coerced people in Java and the outer islands who were Catholic since the Portuguese Era to convert to the Dutch Reformed faith. The freedom of religion was granted in the East Indies when Herman Willem Daendels (1808–11) was the governor-general.