In the Chinese Book of Sung (宋書) it was described that “A certain country, written in Chinese as ‘呵羅單國’ had ruled Java, the country had sent envoys to China three times in 430s AD, that the king of the country was usurped from his position for a while....” Ever since the record received attention in the late nineteenth century, the identity of the country had been a matter of debate among historians. Some of them assumed the country would have existed somewhere in the Malay Peninsula, but others thought it must have been in the Island of Java. In 1980, an Indonesian scholar published an idea that the name of the country which was first transliterated and read in alphabet as “Ho-lo-tan” would have corresponded to Aruteun of Ci-aruteun River in West Java. The same idea independently occurred to the present author some years later as detailed in his book, “Java Essay”, published in 2013 and 2015 in Japanese and English.

Meanwhile in West Java, several stone monuments, locally called “prasasti”, were found piece after another in and after the mid-nineteenth century and, from the fragmental epigraphs, it was established that a kingdom named Tarmanagara had existed around the fifth century, that the kingdom was ruled by King Purnawarman at least for a certain period and that the king’s family had worshipped Hinduism, although the whole figure of the kingdom remained obscure.

Whilst no historical documents which must have been written in ancient times existed, a group of documents, which is said to have been compiled in the court of Cirebon in the late 17th century and called Naskah Wangsakerta (Wangsakerta Manuscripts), was collected in the 1970s by a member of the State Museum of West Java Province, Bandung. Although the authenticity of the documents was questioned by senior archaeologists, one of them, Pustaka Pararatwan i Bhumi Jawadwipa Parwa 1, Sargah 1 (The Book of the Stories of Kings on the Soil of Java Volume 1, Issue 1), hereinafter PPBJ 1-1, described the events in West Java from the primeval times to the period of Tarumanagara quite in detail.

During the last decade the present author has tried to identify the Ho-lo-tan Country, translating the relevant part of the Book of Sung into Japanese and English and studying the Indonesian text of PPBJ 1-1, and has become convinced that Ho-lo-tan Country was another name of Tarumanagara, the capital of which was located on the bank of Ci-aruteun (Aruteun River) that ran, and still runs, through the present-day Desa Ciaruteun Ilir, Kecamatan Cibungbulang, Kabupaten Bogor (where the stone monuments, viz. Prasasti Ciaruteun and Prasasti Kebon Kopi, were found).

Manuscripts written about the results have been submitted to several history journals but rejected, if not ignored, saying that the author should consult with an expert of ancient Chinese language, the Wangsakerta Manuscripts were not approved as historical documents, etc. The academia of history and culture might be more or less exclusive and conservative, compared to that of science and technology with which the author was familiar. A professor whom he visited seemed not much interested in the work of an outsider.

Although his own website was a possible medium, the author has thought that, if published as a book, this work may have more chances to draw the attention of those who are concerned with the subject.

Three appendices, 1: The Pronunciation of Key Chinese characters (假, 羅, 單, 津, 婆), 2: Hindu Calendar/Saka Calendar, and 3: Test-translation of PPBJ 1-1, Part II, have been added.

Any criticism and comments are welcome.

Masatoshi Iguchi

Tokyo, Japan.

E-mail: maiguch@gmail.com

Website: http://www.maiguch.sakura.ne.jp/

March 2021

The interpretation of the text in the Book of Sung was helped by Prof. Naohiro Matsunami, Department of Philosophy, Gakushuin University, Tokyo. The English translation from the Indonesian text of Pustaka Pararatwan i Bhumi Jawadwipa Parwa 1, Sargah 1 was kindly checked by Prof. Iratius Radiman, Bandung Institute of Technology. The contents of this book were intensively discussed with Raden Ayoe Ekowati Sundari, M. A., The National Museum of Indonesia, Jakarta. The author expresses his sincere thanks to abovementioned persons, as well as anonymous Indonesian colleagues, from whom he received a great deal of knowledge about the history and culture of Indonesia. Special thanks are due to Prof. Malcolm Mackley, Cambridge, who kindly read and edited the draft to bring it up readable as English. The final manuscript was checked by my granddaughter, Kanako, a student in Hokkaido University.

Dr. Masatoshi Iguchi, born in 1938 in Nagoya, Japan, had finished the Graduate School of Tokyo Institute of Technology, awarded a doctor of engineering in 1966. He served most of his career time for a governmental research institution under the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, Japan, to work in the area of polymer science and technology until retired in 1999. Then, he obtained a fellowship from the Science and Technology Agency, Japan, and worked at Bogor Research Station for Rubber Technology, Bogor, West Java, Indonesia, for three years. After retired from full-time occupations in 2002, he became interested also in the history and culture, viz. of Indonesia. He published the following books in the category of history and culture.

(1) Marquis Tokugawa, Journeys to Java - translated by M. Iguchi, ITB Press, 2004.

(2) Marquis Tokugawa, Perdjalanan moenoedjoe Djawa, diterjemahkan oleh Ririn A, dan Aprianti I., Penerbit ITB 2006 (Retranslation to Indonesian from the above English translation).

(3) Masatoshi Iguchi 井口正俊, Java Quest: The History and Culture of a Southern Country ジャワ探究 - 南の国の歴史と文化, Maruzen, Tokyo 丸善, 東京 2013

(4) Masatoshi Iguchi, Java Essay: The History and Culture of a Southern Country, Troubador, Leicester 2015.

(5) Masatoshi Iguchi, Gutta Percha: A Journey, With Appendices on Xylonite (Celluloid)/Amber & Copal , Amazon.com, 2021.

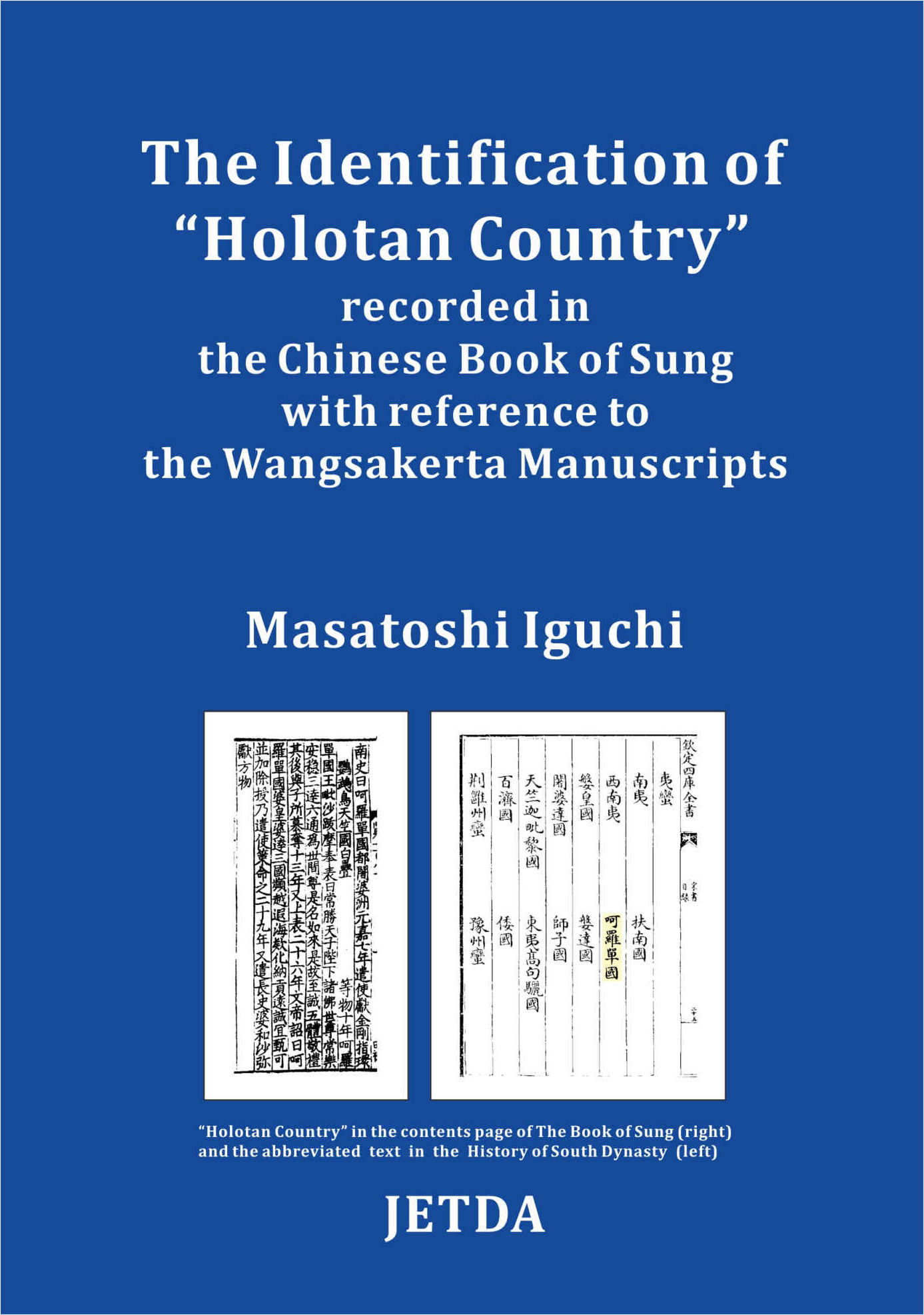

"Holotan Country" in the cntents page oof The Book of Sung (right) and the abbrevviated text in the History of South Dynasty (left).

(Top row)

A Wangsakerta Manuscript (left) and the collective volumes (right) in The Ajip Rosidi Library. Photographs from: https://www.kairaga.com/2019/08/01/naskah-kuno-koleksi-perpustakaan-ajip-rosidi/

(Middle row)

Prasasti Ciaruteun, Prasasti Tugu and Prasasti Cianten of Tarumanagara Era (from left to right). Photographs taken by M. Iguchi, 2006, 2006, 2015.

(Bottom row)

Congklak game arena (left) and large foundation stones (middle and right) in Ciaruteun Ilir Village. Photographs taken by M. Iguchi, 2006.

Introduction

Modern studies on the ancient history of Java that started in the late nineteenth century has relied primarily upon relics, viz. stone inscriptions, as documents which must have been written from time to time did not remain, presumably neglected or destroyed in the course of Islamic Invasion. In fact, even copies of such chronicles or books of historical interest, such as Pararaton[1], Nagarakertagama[2] and Kidung Sunda [3], written in the Majapahit Period, which are available today, were those discovered after the late nineteenth century in Bali or Lombok, where Javanese nobles had evacuated with their belongings. Such epics as the Javanese-version Ramayana, Bharatayuddha, Krsnayana, Bhomakawya (Bhomantaka) etc. composed between the ninth and twelfth century did not remain either in Java. [4] The copy of Bujangga Manik, a story of pilgrimage of a prince and monk of Pajajaran Kingdom that gives useful knowledge about the topography and the customs and manners of the fifteenth-sixteenth centuries Java was somehow taken to England and stored in a library at Oxford since 1627 or 1629 [5].

In West Java, several stone monuments, namely Prasasti Ciaruteun, Prasasti Kebon Kopi, Prasasti Jambu, Prasasti Tugu and Prasasti Cidanghiang, which bore Sanskrit phrases written in Pallava scripts, were intensively studied ever since the mid-nineteenth century, and it was established that a certain kingdom named Tarumanagara had existed around the fifth century, that the kingdom was ruled by King Purnawarman at least for a certain period and that the king’s family had worshipped the Hinduism. From the style of scripts, the founder of the kingdom was assumed to have come from Pallava, India, and, from the distribution of these monuments, the power of the kingdom was considered to have ranged over a significantly wide area of West Java. The details will be reviewed in Chapter 2.

In China, the chronicle of every dynasty, specifically from the Former Han Dynasty (206 BC-8 AD) to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD), included the history of the countries which had contemporarily existed in Southeast Asia and elsewhere in the world. In The Book of Sung (the Southern Sung Dynasty, 420-479 AD), it was recorded that a certain country, written in Chinese as “呵羅單國”, ruled the province of Java (闍婆), the country sent envoys to China in 430 AD, ….” In the late nineteenth century this record had received the attention of G. Schlegel [6], who assumed, or “identified” in his own term, that the country which he transliterated into alphabet as Holotan or Kalatan, must have corresponded to Kĕlantan or Kĭlantan on the Malay Peninsula. The location of the country was debated thereafter by a number of scholars, somehow adopting the above transliteration, “Holotan” or “Ho-lo-tan”, as it was. Whilst L. L. Moens [7] was of the same view as Schlegel, Paul Pelliot[8], K. A. Nilakanta Sastri[9], O.W. Wolters[10], et al. considered that Holotan would have been located in the island of Java. R. C. Majumdar[11] in particular believed that it was in West Java where Tarumanagara Kingdom prospered.

A peculiar idea that Holotan Country (呵羅單國) was the phonetic transcription of Sailendra was once presented by K. Iwamoto, [12] but this theory is considered of little value, firstly because no linguistic explanation was given, and secondly because the rise of the Sailendra was around the mid-eighth century (in the Central Java), whereas the records in The Book of Sung was issued in the early fifth century. Rather recently S. Suzuki [13] voiced a theory that Holotan was not in Java Island but Kelantan on Malay Peninsula, without referring to Schlegel’s and Moens’s papers, and that the Malayan country had ruled a part of Java, asserting that Java at that time had not been civilised enough to be able to send missions to China, whether an audience would lend his/her ear or not.

To what extent these authors looked into the relevant Chinese text in The Book of Sung is unknown, except for Schlegel [14] who gave a short abridged translation (ca. 90 characters from ca. 945 characters).

In any case, the origin of the country does not seem to have been determined so far.

In an essay published in 2013/2015 [15], the present author has assumed that the three Chinese characters for the country’s name (呵羅單), originally transliterated as Ho-lo-tan, could alternatively be read as “A-ro-tan” and that the A-ro-tan Country was the representation of Tarumanagara by the name of its capital which would have existed at least for a period around the present-day Ciaruteun Ilir Village (Ilir = downstream), where Prasasti Ciaruteun and Prasasti Kebon Kopi were found. In the same essay, he also reported for the first time on two other stone relics, i.e., a game arena situated on the ground and a score of foundation stones for pillars of a large building, possibly a palace or a pavilion, allegedly of the Tarumanagara age.

It must be acknowledged, however, that a theory to regard Holotan as Aruteun had been published earlier by Slamet Muljana in 1980 [16] a few years before the same idea occurred to the present author. The existence of the rather rare book came to notice to the present author in a later year in a local bookstore in Bogor. It was the time when Internet search was yet to be available. The details of the theory will be discussed in Chapter 3.

Although no contemporary documents other than those on stone inscriptions remained, the history of ancient times from prehistoric times down to the New Mataram Era was recorded in the so-called Naskah Wangsakerta (Wangsakerta Manuscripts), which are said to have been compiled in the 17th century in Cirebon by Pangeran Wangsakerta (Prince Wangsakerta) and his committee members, assembling old fragmental records and oral traditions.

The manuscripts were elaborately collected by Drs. Atja in the 1970s and intensively studied by Dr. Edi S. Ekadjati,[17] Dr. Ayatrohaedi[18] et al. Sejarah Bogor (A History of Bogor), authored 1983 by Drs. Saleh Danasasmita[19], was one of the earliest publications in which knowledge from the stone inscriptions were complemented and the genealogic relationships between kings and lords analysed.

Meanwhile, the authenticity of the Wangsakerta Manuscript, whether the contents were not fake, was argued after the 1980s by senior archaeologists, viz. Dr. Boechari[20], Prof. R. Soekmono[21], Prof. R. P. Soejono [22], et al., who suspected they were not written by Prince Wangsakerta and his team in the 17th century but were fabricated by someone in the early 1960s after the publication of Prasasti Indonesia II by Prof. J. G. de Casparis in1956[23]. Even the existence of Prince Wangsakerta was questioned. The fact that the manuscripts gathered were not the originals but copies was also reason for dissatisfaction.

These criticisms were countered by Drs. Atja[24], Dr. Ayatrohaedi[25], Prof. Edi S. Ekadjati[26], Prof. Nina, H. Lubis[27], et al., verifying that the Prince Wangsakerta was a real character and that his purpose was basically to “reproduce” the history, as such deeds were undertaken in the East and Central Java and elsewhere in the world. It was also claimed that the availability of old documents only in the form of the copy of copy was common elsewhere. Assuming that Wangsakerta Manuscripts were created by some other person, a question would remain on why the writer had a reason not to publish the works of more than 50 volumes, each consisting of 150 to 280 pages, by his/her own name.

Most relevant articles have been compiled in Polemik Naskah Pangeran Wangsakerta[28]. As a whole, the present author had an impression that negative opinions were more or less conservative and fundamentalistic. The descriptions about Tarumanagara Kingdom in Pustaka Pararatwan i Bhumi Jawadwipa Parwa 1, Sargah 1 (lit. The Book of the Stories of Kings on the Soil of Java Volume 1, Issue 1)[29], hereinafter PPBJ 1-1, at least, seems to be informative, as will be discussed in Chapter 4.

In this book, after reviewing the contents of stone monuments of the Tarumanagara Era and carefully examining and translating the text in The Book of Sung (宋書), the abovementioned assumption that the Holotan Country (呵羅單國) would have been a synonym of Tarumanagara will be discussed in comparison with relevant descriptions in the Wangsakerta Manuscripts, namely PPBJ 1-1.

Inscriptions on the prasasti of Tarumanagara era and notes on stone relics in Aruteun village

Seven stone monuments are known today. Although the results of transliteration and translation of the epigraphs as well as their origin and features of the monuments have been given in various publications [30], let us briefly review them herewith, adding some comments, for the sake of facilitating later discussion.

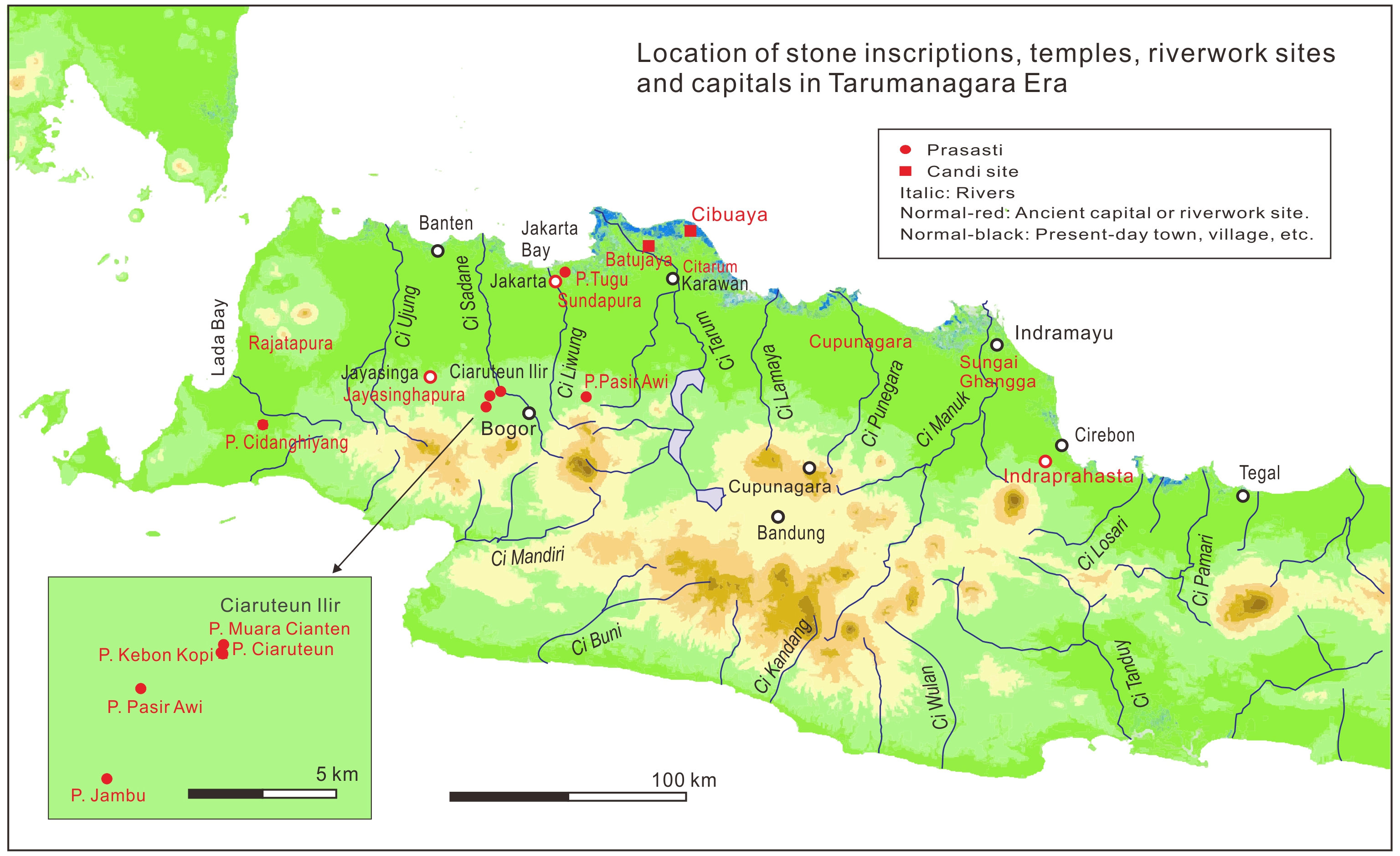

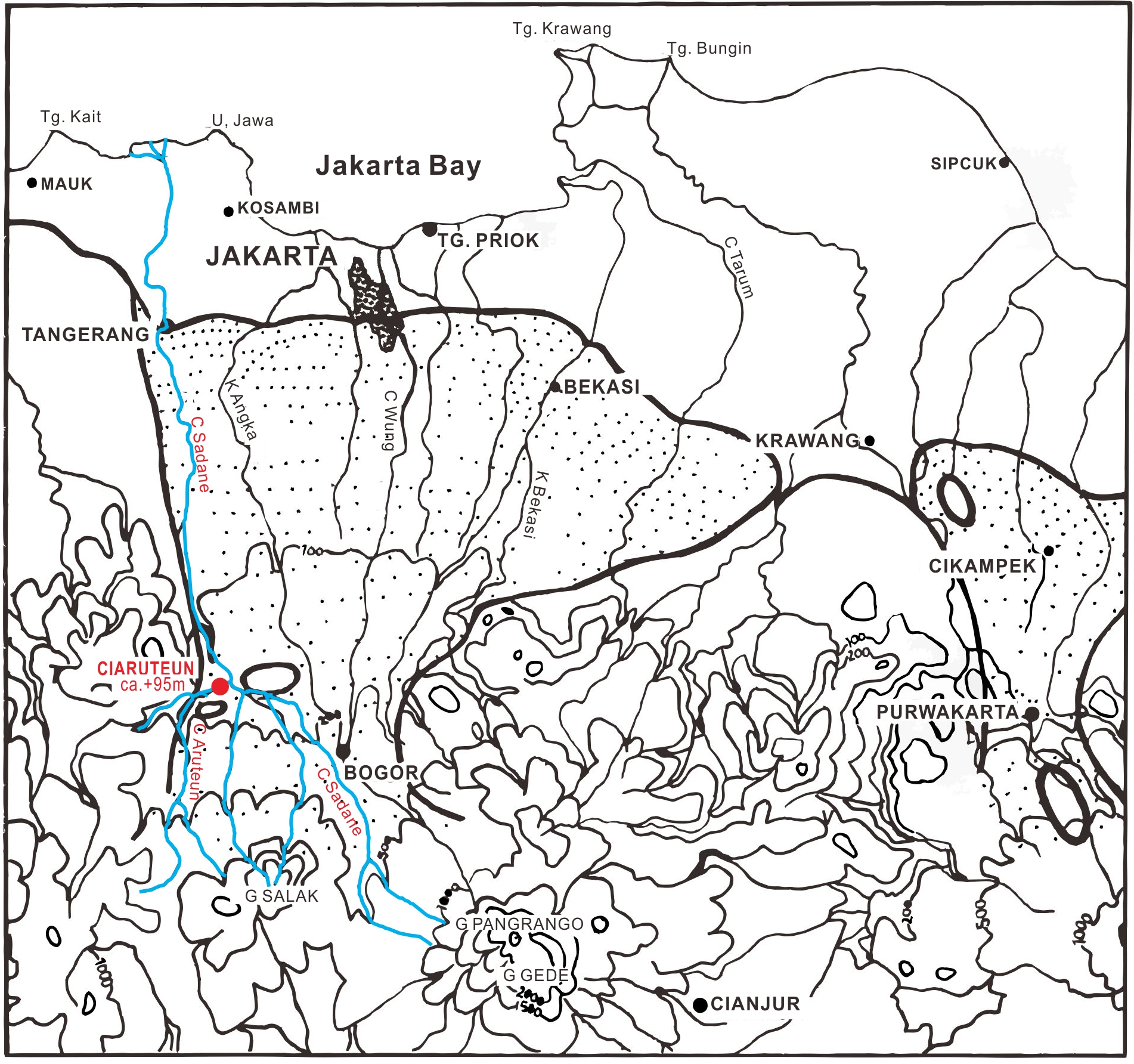

Figure 1 shows the location of stone inscriptions, as well as temples, riverwork sites and capitals, in Tarumanagara Era.

|

Figure 1 Location of stone inscriptions, temples, riverwork sites and capitals in Tarumanagara Era. The topological map has been prepared with DIVA-GIS/Country Data (Indonesia). |

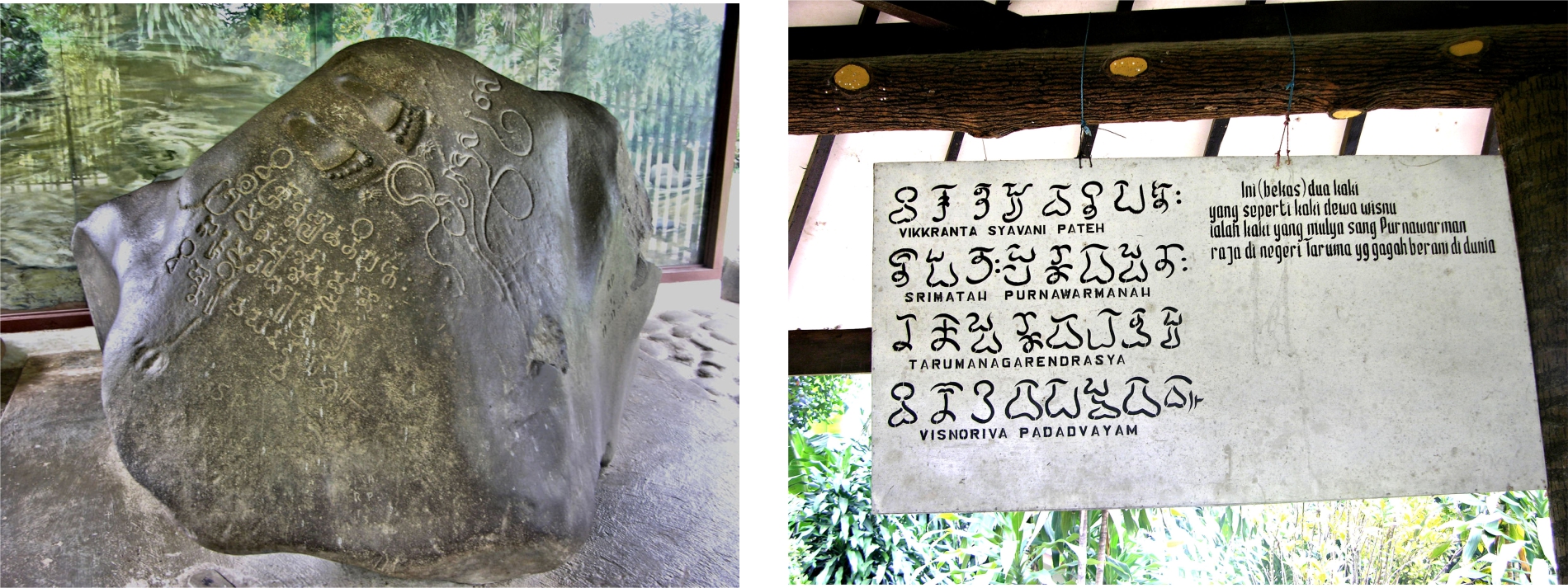

This stone monument was found in a riverbed of Ciaruteun (Aruteun River) in Desa Ciaruteun Ilir, Kecamatan Cibungbulang, Kabupaten Bogor in the 1860s. It was a round natural rock of about 2.2 metres wide and 1.4 metres high, on the surface of which were carved a pair of human footprints and some symbolic letters (Figure 2). The symbols inscribed were similar to those used in the Pallava Empire which prospered in India in the fourth-fifth centuries and used Sanskrit as their language. The large symbols on the right-hand side of the footprints were decoded in the early days as “The King Purnawarman of Tarumanagara”, and the strings of small symbols on the left-hand side were deciphered in the 1920s. In English, it said:

|

Of the valiant lord of the earth, the illustrious Purnawarman, [who is] the ruler of the town of Taruma, [has] the pair of footprints like unto Vishnu’s . [31] |

This suggested that King Purnawarman of Tarumanagara was regarded and respected as the incarnation of the Hindu God Vishnu, or an existence with a similar divinity.

| Figure 2 Prasasti Ciaruteun and the epigraphs on it. Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

This stone monument found in a coffee plantation, not far from Prasasti Ciaruteun, and reported also in the 1860s (Figure 3) is alternatively called “Prasasti Telapak Gajah” because a pair of elephant’s footprints are carved on it. The Sanskrit text inscribed between the two elephant’s footprints said:

|

Here appeareth the pair of foot-prints of the (brilliant) Airawata-like elephant of the Lord of Taruma [who is] great in strength and victorious . [32] |

Since Airawata was the white elephant that was the vehicle of Indra, the God of War,[33] the king and his family is supposed to have believed in the Hinduism. Since endemic Javan elephants (Elephas hysudrindicus) had become extinct before the historical time[34], the elephants are supposed to have been brought from Sumatra or the Asian continent by the king and his followers.

| Figure 3 Prasasti Kebon Kopi and the epigraphs on it. Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

This rock inscription, also called “Prasasti Pasir Koleangkak” which existed on a hillock named Pasir Koleangkak, in Kebun Jambu [35], Desa Parakanmuncang, Kecamatan Nanggung, about 30 km to the west of Bogor, was known since the 1850s. A two-line Sanskrit verse was read as:

|

Illustrious, munificent, and true to his duty was the unequalled lord of men – the illustrious Purnawarman by name – who once [ruled] at Taruma and whose famous armour (varman) was impenetrable by the darts of a multitude of foes. His is this pair of footprints which, ever dextrous in destroying hostile towns, is salutary to devout princes, but a thorn in the side of his enemies .[36] |

This stone monument is considered to have been erected after Purnawarman’s death as a eulogy to record that Purnawarman was an excellent warrior.

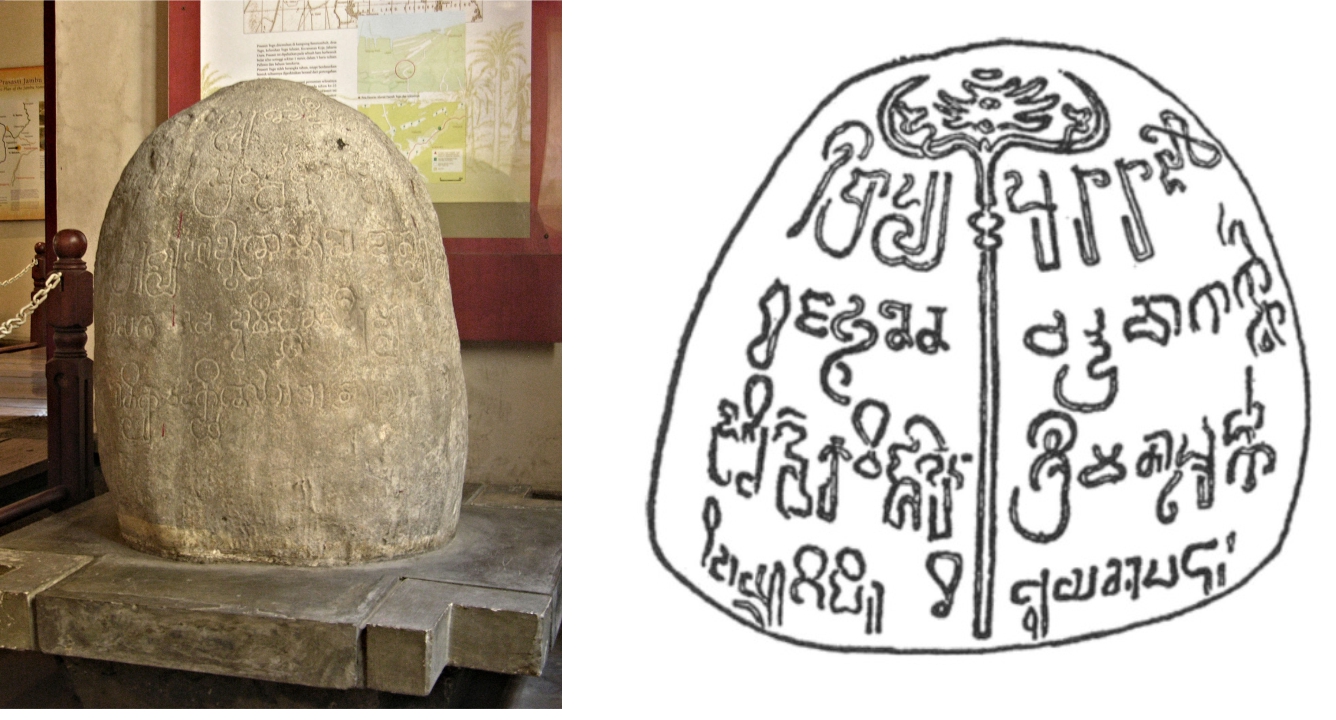

This stone monument (Figure 4) had formerly exposed only 10 cm of its head on the ground, near the coast to the east of Tanjung Priok, in Desa Tugu, Kecamatan Koja, North Jakarta. Local people offered flowers and burnt incense in its side. When dug out in 1879, it was revealed that it was a round-triangular or egg-shaped stone of about one metre height and that on the surface of it was an epigraph of a five-line, 100-word poem recording the riverworks conducted during the time of King Purnawarman. It was translated as follows:

|

Formerly the Candrabhaga dug by the king of kings, the strong-armed Guru [the King’s father?], after having reached the famous town, went to the ocean. In the twenty-second year of [his] increasing, prosperous reign the illustrious Purnawarman – who shineth forth by prosperity and virtue and who is the ornament [lit. the banner] of the rulers of men – hath dug the charming river Gomati pure of water, long six thousand, one hundred and twenty-two bows [dhanus], having begun it on the eighth lunar day of the dark half of [the month of] Phalguna and completed it on the thirteenth lunar day of [(the white half) of the month of] Caitra. [The river] which had torn asunder the camping-ground of the Grand-father and Royal Sage, now floweth forth, after having been endowed by the Brahmins with a gift of a thousand kine [cows] .[37] |

| Figure 4 Prasasti Tugu (Replica), Jakarta History Museum (photographed with permission by. M. Iguchi, September 2006) and a part of epigraphs on it (duplicated from Bosch, F. D. K.: Selected Studies in Indonesian Archaeology, The Hague Martinus Nijhoff, 1961). |

This description is ambiguous in some parts. Firstly, although Candrabhaga and Gomati were probably named after the rivers that had existed in India, it was not sure to which rivers in West Java they actually corresponded. Assuming that the stone inscription was placed at the site of the riverworks, Candrabhaga was regarded as the present-day Bekasi River, and the river name was interpreted to have derived as:

candrabhaga → sesibhaga → bhagasasi → bagasi → bekasi,

by R. M. Ng. Poerbatjaraka [38], whereas the fact that the location of the stone inscription was closer to the Cikajang River was pointed out.[39] Secondly, it was doubted whether it was possible to dig a river or a canal of such a length as 6,122 dhanus, which is assumed to be 7 miles (11.3 km) or 12 miles (22.9 km) within a matter of twenty-one days [40]. The year of the work was not written. Thirdly, the relationship of Purnawarman to “the king of kings” or the Grand-father and the Royal Sage was obscure. [41] Notwithstanding, the records suggested that the rulers such as Purnawarman had made efforts to manage rivers in West Java which often flood even today, and that Tarumanagara ruled the area as a solid settlement.

This stone monument, often called “Prasasti Lebak” or “Prasasti Munjul”, was found in 1947 on the edge of Cidanghiang River, in Desa Lebak, Kecamatan Munjul, Kabupaten Pandeglang, Banten. The two-line inscription on it was deciphered and translated in the 1960s as:

|

This is the conqueror of the three worlds (with his three steps), his majesty king Purnavarman, the great king, the hero, (and) to be the banner of all kings in the world .[42] |

or

|

Illustrious, munificent, and true to his duty was the unequalled lord of men – the illustrious Purnawarman by name – who once [ruled] at Taruma and whose famous armour (varman) was impenetrable by the darts of a multitude of foes. His is this pair of footprints which, ever dextrous in destroying hostile towns, is salutary to devout princes, but a thorn in the side of his enemies .[36] |

The content was another homage to King Purnawarman but the fact that this stone inscription was located far away from others manifested that the power of Tarumanagara had ranged over a wide area of West Java. In respect to this inscription an interesting comment is found in an article [44] that can be paraphrased as “Before our ancestors got the guidance of the Islamic Almighty God, they needed a person, king, community chief or whosoever, who gave guidance for their life”. To the author’s understanding, this is still true today particularly among average people in the island of Java.

This rock inscription (shown in Figure 5) was found in the 1860s in the riverbed of Cisadane River near the junction point of the tributary Cianten River, as “muara” meant river end, in Kecamatan Cibungbulang, Bogor, not far from Desa Ciaruteun Ilir where Prasasti Ciaruteun and Prasasti Kebon Kopi were found. Besides some botanical ornaments which look like runners protruding out of tubers, some curly symbols are sculptured, but what they mean has not been clarified. [45]

| Figure 5 Prasasti Muara Cianten. Photographed by. M. Iguchi, February 2015. |

This inscription was found in the 1860s in the Cipamingkis forest on the southern slope of the Pasir Awi Hill in Desa Sukamakmur, Kecamatan Sukamakmur, Bogor. On the surface were carved a pair of footprints and some curly patterns. The latter could be some letters but not be deciphered. [46]

In summary, it was proved from these seven inscriptions that:

(i) A certain kingdom named Tarumanagara had existed around the fifth century in West Java.

(ii) The kingdom was ruled by King Purnawarman (at least for a period).

(iii) The king’s family had worshipped the Hindu gods, viz. Vishnu and Indra.

(iv) The founder of the kingdom is supposed to have come from Pallava, India, from the style of the script.

(v) The rulers made efforts to manage rivers in their territory.

(vi) The power of Tarumanagara ranged over a significantly wide area of West Java.

Nevertheless, the following points remained questionable.

(i) The relationship of Purnawarman to “the king of kings” or the Grand-father and the Royal Sage are obscure.

(ii) The identity of the Candrabhaga and Gomati rivers is not certain.

Besides the abovementioned seven stone monuments, one more monument, called “Prasasti Pasir Muara”, was found in Ciaruteun Ilir Village in the nineteenth century and said to have been somehow lost in the 1940s. The text written with Kawi script in Old Malay was deciphered by F. D. K. Bosch [47] as,

|

This is the monument issued by Rakryan Juru Pangambat in [the year of] 854 [Saka] (936AD) to notify that the ruler of Sunda will be restored in the former state . [48] |

Although in the normal manner the three figures of the year should be read from the right to the left as 458 Saka, Bosch put them the other way round as 854 Saka (932 AD), because the year, 458 Saka, was too early for the use of the Malay language. Thus, this inscription was not included in the monuments of Tarumanagara Era.

(8) Congklak arena and large foundation stones in the Aruteun Village

As briefly mentioned above, when the present author visited Aruteun village, the caretaker of the archaeological site guided him to a spot, not far from the places of Prasasti Ciaruteun and Prasasti Kebon Kopi, where five pieces of stone of some half a metre diameter remained. Two of them embedded in the ground had semi-spherical holes of 6–7 cm diameter on the flat surface, about twenty together (Figure 6). As his friend admired, it must be an arena of a game called “congklak” in Sundanese, alternatively called “dakon” in Javanese or “mancala” in Europe, which is still popular today among children in Indonesia as a table-top intellectual game. Although different theories say that the origin of the game was not in India but somewhere in Arab or Africa, it is certain that the game was introduced into this site by the immigrants from India who founded Tarumanagara. It was amusing to imagine that ancient people were playing the game around these stones.

The caretaker also showed us several pieces of granite blocks of about 50-cm cubic shape, with a hollow of about 40 cm square and 5 cm depth on one of their surfaces, having been collected and laid under the eaves of his house (Figure 7). Several more pieces were found scattered in a near-by banana field. The stone blocks must have been the foundation stones of a building and, judging from the size of pillars to fit the square hollow, the building is considered to have been a big palace or pavilion of King Purnawarman which had stood at that site.

| Figure 6 Play arena of congklak in the Aruteun Village. Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

| Figure 7 Stone blocks, which are supposed to be the foundation stones of large construction of Tarumanagara age, collected under the eaves of a house (left) and one of the blocks remained in a banana field. Photographed by M. Iguchi, September 2006. |

The caretaker told us that the name of Darmaga village halfway from Bogor, well known as the site of the new campus of Bogor Agricultural University, would have been originated from King Dharmayawarman, the predecessor of Purnawarman, although no substantial evidence was available.

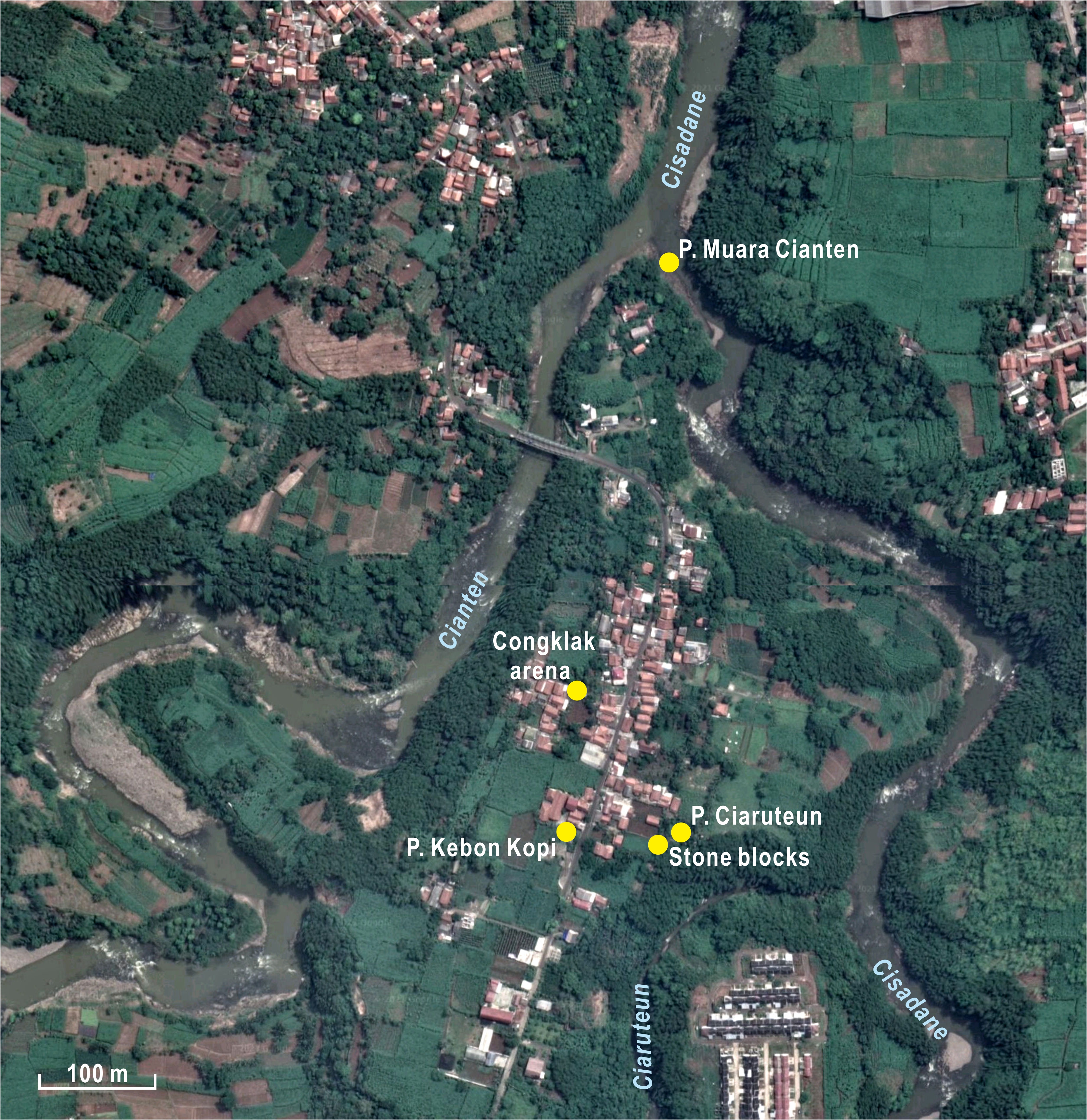

| Figure 8 The area where Ciaruteun and Cianten Rivers merge to Cisadane River. Prepared on the Google Map. |

Before ending this chapter, let us focus on a small area, shown in Figure 8, where Ciaruteun and Cianten Rivers merge to Cisadane River, in which five Tarumanagara relics, i.e., Prasasti Ciaruteun, Prasasti Kebon Kopi, Prasasti Muara Cianten, congklak arena and foundation stone blocks, remain. This area is supposed to have been the centre of Tarumanagara Kingdom for a certain period, as will be discussed in the next chapter.

Full translation of the records on the “Holotan Country” in The Book of Sung

In common with other old books, The Book of Sung (Sun Shu, Vol.97, Biography Series 57, Barbarians 宋書卷97, 列傳第57, 夷蠻) [49] was written with no punctuations and brackets. The source text [50] comprised 776 characters to which 169 punctuations and brackets were added by the editor. For convenience, the text was divided into 8 paragraphs as below.

Paragraph 1 described the governance of the country.

|

(1) |

|

呵羅單國治闍婆洲。 |

|

Aruteun Country rules the province of Java. |

The reason to read the county’s name, 呵羅單, as “A-ro-tan” and regard it as the transliteration of “Aruteun”, was hinted by a Chinese descent in Jakarta, an acquaintance of the present author, who was not a linguist but talented in language. When questioned, she answered that the original sound for the name would have been “a-lo-tan”, or possibly “a-ro-tan”. The ambiguity is ascribed to the fact that, although the middle character, 羅, is usually pronounced as “lo” or “luó”, it is also applied to the sound of “ro” in the words of foreign origin, e.g., 羅馬 (Rome), 歐羅巴 (Eu rope) etc. Then, an idea that the three Chinese characters must be the transcription of “Aruteun” of Ci-Aruteun (Aruteun River), where the Prasasti Ciaruteun and the Prasasti of Kebon Kopi were found, flashed into the present author’s mind.

Perhaps the sound of the first character, 呵, is controversial. Although “ho” seems to be common for idioms in the Wage-Giles system as actually adopted for transcribing the country’s name as “Holotan”, the basic sound was “a” or “ā” and used for such words of foreign origin as “a cha chia” for 呵吒迦 (Skt. hāṭaka), “a lo lo” for 呵羅羅 (Skt. Atata, the third of the eight cold hells), etc. The third (last) character, 單, has no other choices but “tang” in Wage-Giles and “dan” in Mandarin. [51]

Let us also examine the province name, 闍婆, which was traditionally transcribed in alphabet as “She-po”. Although the first character is usually pronounced as “she” or “tu”, it is also of use for “ja” for Sanskrit words, such as yojana (踰闍那, length unit, ca. 7 km), Jātaka (闍陀迦, stories of previous life), etc. The common sound of the second character, 婆, is “po” but the character is also used for “va” as in the Sanskrit words, “Shiva (濕婆)”, “Deva (提 婆)”, etc. More examples are shown in Appendix 1.

The theory of Muljana[52], mentioned above, was obtained in a different way, as he emphasised, from “toponym” or the study of the name of places derived from topographical features.

(1) In West Java, there are many places named Ciliwung, Cisadane, Citarum etc. which bear prefix, “Ci-”, meaning water.

(2) A kingdom located close to the sea at the mouth of a river was often called by the name of the port.

(3) Fifteen centuries ago, when the alluvial sediment of Cisadane was far less than today, the river is supposed to have had a long estuary and a port existed at the upper end, near the present-day Ciaruteun Ilir, where Ciaruteun River joins Cisadane River.

As to the backword transliteration of “Holotan” to Aruteun, the author just mentioned that “Holotan and Aruteun show a very similar sound”. [53]

With regard to Cisadane River, although whether the estuary had ranged up to the present-day Ciaruteun Ilir is uncertain, it must have been the sole waterway for transportation from this point to the Java Sea, as still is. Figure 9 is a raft seen in a recent year near the river junction.

| Figure 9 A raft in Cisadane River near the junction point of Cianten River seen from the top of Muara Cianten rock. Photographed by M. Iguchi, January 2015. |

Figure 10 shows the alluvial sedimentation around the Jakarta Plain, a work by H. Th. Verstappen.[54] According to the Google Earth, the height of the riverbed of the Ciaruteun’s downstream is ca. +95 metres above sea level. It must have been lower than that in the Tarumanagara Era.

| Figure 10 Alluvial sedimentation around the Jakarta Plain toword Jakarta Bay. Original map by H. Th. Verstappen (Dithertation 1953), in: Suryomiharjo, Abdurrakhman, The growth of Jakarta, Djambatan, Jakarta 1977 [55]. Redrawn on CorelDRAW and the location of Ciaruteun Ilir has been added, Cisadane, Ciaruteun and Cianten Rivers shown in blue by the Author. |

Muljana further claimed that “Aruteun Kingdom was the first ever kingdom existed in Java Island before Tarumanagara” and that “the kingdom was conquered or subordinated by Purnawarman of Tarumanagara”. These claims are not appropriate, if referred to the Wangsakerta Manuscript which described that Salakanagara was the first kingdom founded in West Java and that the kingdom was passed down to Jayasinghawarman who married to the daughter of the last king of Salakanagara, Dewawarman VIII, and established Tarumanagara. Purnawarman was a son of Jayasinghawarman (See, Chapter 4).

Back to The Book of Sung, Paragraph 2 described the sending of a mission to China in 430 AD and the list of tributes.

|

(2) |

|

元嘉七年, 遣使獻金剛指鐶, 赤鸚鵡鳥, 天竺國白疊古貝, 葉波國古貝等物。 |

|

In the 7th year of Yuanjia (430 AD), [the country] sent an envoy and presented a gold ring, red parrots, white fine cotton fabrics from Tianzhu (天竺國), cotton fabrics from Kasyapa (葉波國), etc. |

Among the listed tributes, the gold ring might have been a native product from Java but the red parrots were allegedly the species captured somewhere in Nusa Tenggara (Lesser Sunda Islands beyond Bali, in the eastern side of the Wallace Line) or their offspring. This suggests that the country had interaction with such remote areas. The cotton fabrics from Tianzhu and Kasyapa imply that the country had trade relations with India.

Paragraph 3 recorded a letter from the king of Aruteun submitted probably by a messenger in the 10th year of Yuanjia (元嘉), 433AD. The letter was a long one in which as many as 234 characters were spent for the homage to the Chinese emperor, who is identified as Emperor Wen (文帝, reigned 424-453 AD) of Liu Sung (劉宋).

|

(3-1) |

|

十年, 呵羅單國王毗沙跋摩奉表曰: |

|

In the 10th year (433 AD), the King of Aratan, Wisnuwarman submitted a letter and said, |

|

常勝天子陛下: |

|

The Ever-winning Your Majesty [Emperor Wen [文帝] of Liu Song, Esq! |

|

諸佛世尊, 常樂安隱, 三達六通, 爲世間道, 是名如來, |

|

Buddha and Sakyamuni are in the state of eternal bliss and the three kinds of wisdom (三達) and six kinds of supernatural powers (六通) are used for the guidance for the world. This is named Tathagata (如來). |

| (3-2) |

| 應供正覺, 遺形舍利, 造諸塔像, 莊嚴國土, 如須彌山, 村邑聚落, 次第羅匝, 城郭館宇, 如忉利天宮, 宮殿高廣, 樓閣莊嚴, 四兵具足, 能伏怨敵, 國土豐樂, 無諸患難。 |

| With the bones of truly enlightened Arhat, towers are built and statues are sculptured so that the land of the country is glorious. Thus, as if in Mt. Semeru, villages and towns are spirally developed and the castle walls and buildings soar. As if the Trāyastriṃśa [on the top of Mt. Semeru], the palace is tall and wide and the multistoried pavilion is majestic. Four armies [elephants, horses, chariots and infantry] are perfectly provided and able to beat ambush enemies, the land of the country is prosperous and safe and there is no worry and difficulty. |

|

奉承先王, 正法治化, 人民良善, 慶無不利, 處雪山陰, 雪水流注, 百川洋溢, 八味清淨, 周匝屈曲, 順趣大海, 一切衆生, 咸得 (徳?) 受用。 |

|

We hear of the previous king, the country is ruled according to the true dharma (teaching of Buddha), all people are good and happily no one is disfavoured. Snow remains in mountain slopes and snow water emits and flows full into hundreds of rivers. Clean eight-merit waters wind around the mountain and flow towards oceans. All living beings receive dignity and virtue. |

|

於諸國土, 殊勝第一, 是名震旦, 大宋揚都, 承嗣常勝大王之業, 德合天心, 仁廕四海, 聖智周備, 化無不順, 雖人是天, 護世降生, 功德寶藏, 大悲救世。 |

|

Among various countries and lands, the best is this country that is called the Cinasthana. In the capital Yang (揚都) [of the Great Liu Song], the practice of the Ever-winning Emperor is followed, the virtue accord with the divine’s will and the benevolence is heard over four oceans. |

|

爲我尊主常勝天子。是故至誠五體敬禮。 |

|

“To the respectful ever-victorious Emperor, I would sincerely salute with the whole five parts of my body. |

|

呵羅單國王毗沙跋摩稽首問訊 。 |

|

I, Wisnuwarman, the King of Aratan should like to bow to the floor and press my palms” |

The backward transliteration of the king’s name, 毗沙跋摩, as Wisnuwarman, would be reasonable, as Wisnuwarman actually appeared in the Wangsakerta Manuscripts as the person who succeeded the throne of Purnawarman and made efforts to keep friendly relationships with China and other foreign countries, as will be mentioned in Chapter 4.

The long and courteous homage seems to show the subordinate position of Aruteun to Liu Sung, although such homage would have been a common protocol at that age. The fact that great many phrases were cited from Buddhist sutras suggests that the king of Java and probably his guru were well versed in Buddhist philosophy despite the fact that their religion was Hinduism, even if the fact that the Buddhism had hierarchically derived from the Hinduism is taken into account. For writing Chinese, they would have received assistance from the ambassador from China stationed at their capital.

Paragraph 4 wrote about an incident, a coup to usurp the throne.

|

(4) |

|

其後爲子所篡奪。 |

|

After then, a bad child (an evil man) usurped the throne [of Aratan]. |

Paragraph 5 recorded another long letter of 390 characters from King Wisnuwarman sent to China in the 13th year of Yuanjia (元嘉), 436 AD. After a long homage, the king wrote that he had lost his position by the coup d’état but had a strong will to revenge and that he wished the Emperor would help his retainer, dispatched to Liu Sung, with purchasing necessary things and returning home safe.

|

(5-1) |

|

十三年, 又上表曰: |

|

In the 13th year (436 AD), [The Aratan Country] again submitted a letter: |

|

(5-2) |

|

大吉天子足下: |

|

The Great Fortunate Emperor, Esq! |

|

離淫怒癡 , 哀愍羣生, 想好具足, 天龍神等, 恭敬供養, 世尊威德, 身光明照, 如水中月, 如日初出。 |

|

Staying remote from luxuria (淫) and hate moha (or complaint, 癡), being compassionate for living beings, with holy characteristics, and being respected even by heavenly gods and the Dragon God is the dignity and virtue of Shakyamuni which manifest themselves in his body light, like the moon in water or the rising sun. |

|

眉間白豪(毫?), 普照十方, 其白如雪, 亦如月光, 清淨如華, 顏色照曜, 威儀殊勝, 諸天龍神之所恭敬, 以正法寶, 梵行衆僧, 莊嚴國土, 人民熾盛, 安隱快樂。 |

|

His urna (the light-emitting hair in the middle of Buddha’s forehead) enlights all ten directions like white snow and like moonlight. His cleanness is like that of flowers. His face colour illuminates. His dignified manner is most admirable, being venerated and respected by heavenly gods and the Dragon God. With the treasure of true dharma, monks practice asceticism. The land of the country is glorious. People are fierily active, safe and enjoyable. |

|

城閣高峻, 如乾他山, 衆多勇士, 守護此城, 樓閣莊嚴, 道巷平正, 著種種衣, 猶如天服, 於一切國, 爲最殊勝吉。 |

|

The castle (of this country) is lofty as if it were a mountain. Many warriors guard this castle. The palace is majestic. Roads and towns are just flat. Various clothes look like the divine attire. This country is the greatest and most blissful of all countries. |

|

揚州城無憂天主, 愍念羣生, 安樂民人, 律儀清淨, 慈心深廣, 正法治化, 共(供?) 養三寶, 名稱遠至, 一切並聞。 |

|

The Emperor in the peaceful castle of Yang zhou (揚州) is compassionate to living beings and comfort people. Your faith is clean, your benevolence is deep and broad, your governance accords with dharma and you venerate the three treasures [Buddha, dharma and sangha]. Your name reaches to distant places and everything is heard in common. |

|

民人樂見, 如月初生, 譬如梵王, 世界之主, 一切人天, 恭敬作禮。 |

|

People joyfully see you like a newborn moon or a divine king, as if Brahma is venerated as the king of the world by all people and by heavenly gods. |

|

呵羅單跋摩以頂禮足, 猶如現前, 以體布地, 如殿陛道, 供養恭敬, 如奉世尊, 以頂著地, 曲躬問訊。 |

|

I, Wisnuwarman of Aratan would salute with my head on your foot and, in front of you, lay my body flat on the ground which is like a palace’s stairway. I venerate and respect you like Sakyamuni and, bow to the ground by bending my body and pressing my palms. |

|

忝承先業, 嘉慶無量, 忽爲惡子所見爭奪, 遂失本國。 |

|

I had gratefully succeeded the predecessor’s practice and my delightfulness was immeasurable, but soon I was usurped by a bad child (evil man) and eventually lost the country. |

|

今唯一心歸誠天子, 以自存命。 |

|

Now, I wholeheartedly entreat Your Majesty in order to keep my life. |

|

今遣毗紉問訊大家, 意欲自往, 歸誠宣訴, 復畏大海, 風波不達。今命得存, 亦由毗紉此人忠志, 其恩難報。此是大家國。 |

|

Now, I dispatch Wijin (毗紉) and press my palms to Your Majesty. I wish to come myself and implore the situation [but] I am afraid that the oceans, winds and waves may prevent me from reaching your place. Now, I am alive. As to Wijin, he is a man of faith and repaying his favours is difficult. [He is] in this great country. |

|

今爲惡子所奪, 而見驅擯, 意頗忿惋, 規欲雪復。 |

|

Now that the bad child (evil man) is usurped, I suffer [misery of] the expulsion with high resentment and anger, I wish revenge to justify [the situation]. |

|

伏願大家, 聽毗紉買, 諸鎧仗袍襖及馬, 願爲料理毗紉使得時還。 |

|

I bow and wish that Your Majesty would listen to my desire to let Wijin purchase various things, the armour, weaponry, attire (gown and coat) and horses and let him timely return home. |

|

前遣闍邪仙婆羅訶, 蒙大家厚賜, 悉惡子奪去。 |

|

The former envoy Jayasinbalaka (闍邪仙婆羅訶) received Your Majesty’s favours but was robbed of them by the bad man. |

|

啟大家使知,今奉薄獻, 願垂納受。 |

|

Well, I have informed you. Your Majesty, [of my problem]. Now I present humble tributes and wish you to receive them.” |

This coup d’état might correspond to an incident described in the Wangsakerta Document, as will be mentioned in Chapter 4.

Paragraph 6 wrote the arrival of another envoy.

|

(6) |

|

此後又遣使。 |

|

After then, an envoy came again. |

This implies that the king had recovered his position, as actually had, as written in PPBJ 1-1.

Paragraph 7 recorded a decree of the Emperor Wen issued in 449 AD.

|

(7-1) |

|

二十六年, 太祖詔曰: |

|

In the 26th year (449 AD), Taizu (Emperor Wen) said in his decree: |

|

訶羅單, 媻皇, 媻達三國, 頻越遐海, 款化納貢, 遠誠宜甄, 可並加除授 。 |

|

Three countries, Holotan (訶羅單), Bhad (媻皇) and Bhawu (媻達), frequently cross over oceans and sincerely submit tributes. The sincerity of distant countries should be appreciated and proper assignments (除授), be given. |

|

乃遣使策命之曰: |

|

In fact, the letter to the envoy said: |

|

(7-2) |

|

惟爾慕義款化, 效誠荒遐, 恩之所洽, 殊遠必甄, 用敷典章, 顯茲策授。爾其欽奉凝命, 永固厥職, 可不慎歟。 |

|

“I think the longing for affection and justice [of yours] will make your sincerity reach to remote regions. The favour [of mine] will widely range and be found for certain in distant places. Make use of rules and give decrees for it. Firmly bow to duties. How could one fail to behave?” |

In this paragraph, in the names of three countries, the first Chinese character of the first country, Holotan, 訶, was different from that appeared in Paragraph 1, 呵 of 呵羅單. John Guy [56] assumed that the set of three countries, 訶羅單, 媻皇 and 媻達, read as Kelantan, Pahang and Perak, respectively, were the countries that had coexisted in the Malay Peninsula. An Internet article by Koji Sato [57] speculated that the three countries were located in the present-day Viet Nam.

Thus, the present author would assume that the above paragraph had nothing to do with the “Holotan” country in Java, having been erroneously incorporated from some source material during the compilation of The Book of Sung.

The last Paragraph 8 recorded another visit of the envoy.

|

(8) |

|

二十九年, 又遣長史媻和沙彌獻方物。 |

|

In the 29th year (452 AD) again an envoy, Chief Secretary, trainee monk Panho (?) presented local products. |

It is not sure either whether this content was concerned with Tarumanagara.

For reference, the summary of the record on the “Holotan Country” is included in Nanshi (南史, The History of South Dynasty), compiled by Li Yanshou 李延壽 and published in 659 AD in the Tang Dynasty Era, specifically in Vol. 78, Biography Series 68, Surrounding Barbarian 1/2, Maritime Countries [58].

|

(1) |

|

呵羅單國都闍婆洲。 |

|

(2) |

|

元嘉七年,遣使獻金剛指環、赤鸚鵡鳥、天竺國白疊、古貝、葉波國古貝等物。 |

|

(3-1) |

|

十年,呵羅單國王毗沙跋摩奉表曰: |

|

常勝天子陛下,諸佛世尊,常樂安隱,三達六通,爲世間導,是名如來, |

|

(3-2) |

|

・・・是故至誠五體敬禮。 |

|

(4) |

|

其後爲子所篡奪。 |

|

(5-1) |

|

十三年,又上表。 |

|

(5-2) |

|

・・・ |

|

(6) |

|

・・・ |

|

(7-1) |

|

二十六年,文帝詔曰:「呵羅單、婆皇、婆達三國,頻越遐海,欵化納貢,遠誠宜甄,可並加除授。」乃遣使策命之。 |

|

(7-2) |

|

・・・ |

|

(8) |

|

二十九年,又遣長史婆和沙彌獻方物。 |

In this summary, the fifth character (治, rule, govern) in the Paragraph 1 of the Book of Sung was replaced with a different character (都, capital city), so as “Aruteun Country is the capital of the province of Java”, instead of “Aruteun Country rules the province of Java”, although the meanings of the two sentences were virtually the same.

The Paragraph 3-2 was shortened and Paragraphs 5-2, 6 and 7-2 were omitted, whether the compiler had carefully examined and judged the contents extraneous.

As a record of contemporary Java, a passage in A Record of the Buddhist Countries (佛國記) or The life of Faxian (法顯傳) is well known. In 414 AD, a Buddhist priest, Fa Xian (or Fa Hsien, 法顯), from the Eastern Chin (Jin) Dynasty (東晉), arrived, after a hard voyage of ninety days, in Javadvipa (lit. Java Island) on his way back to China from Ceylon and stayed there for five months. He wrote:

|

乃至一國名耶婆提其國外道婆羅門興盛佛法不足言 [59] . |

|

Thus [I have] come to a country named Javadvipa. In this country, the paganism and Brahmanism flourish but Buddhist dharma is trifling. |

Although the name of the kingdom was not explicitly given, the country has been widely accepted as Tarumanagara. “Paganism (外道)” in this passage must have meant the ancestor worshipping of the native Sundanese inhabitants. [60] The word “Brahmanism” was commonly used in China as a synonym of what is broadly called “Hinduism”. Then, this description agrees with the aforementioned assumption derived from the stone inscriptions that the immigrants were “Hindu” worshippers.

Relating descriptions in the Pustaka Pararatwan i Bhumi Jawadwipa

(1) A brief note on the document

The PPBJ 1 covered the chronicles of many countries or kingdoms which rose and fell in Java Island from ancient times to the establishment of New Mataram in the late 16th century. Amongst, PPBJ 1-1 wrote about the rulers and their genealogy as well as the events and achievements in the period from the beginning of Salakanagara to the era of the fourth king of Tarumanagara, Wisnuwarman, preceded by the introduction and the prehistory of primeval times. Leaving aside the argument about the authenticity mentioned in the Introduction (Chapter 1), the data included in the manuscript is considered useful for supplement the knowledge from the stone inscriptions and The Book of Sung, as partly done by Danasasmita [61] for the former.

The book referred to[62] in this work consisted of three chapters:

Chapter I: Introduction,

Chapter II: The text summary,

Chapter III: Transliteration and Translation of the original text.

The second chapter was easy to follow, as the contents of the original text, which were inconsistent in some parts and contained redundant expressions, have been digested and orderly rewritten by the translators, but the unabridged, word-for-word text in the third chapter was also referred to. The test-translation of Chapter II from Indonesian to English is given in Appendix 2.

(2) The founding and the genealogy of Salakanagara and Tarumanagara

The main part of PPBJ 1-1 commenced with the founding of Salakanagara, the first country that had existed on the soil of Java Island before Tarumanagara.

|

In the early 2nd century AD a group of migrants originated from the families of Salankayana and Pallava from the east and the south India, respectively, arrived and eventually settled at a certain place on the west coast of Java Island. Their leader, Sang Dewawarman from Salankayana married the daughter of a local chief and, in 52 Saka (130 AD), founded a kingdom named Salakanagara, probably after Salankayana in India where they came from. The kingdom’s capital was Rajatapura. [63] Dewawarman was the king until 90 Saka (172 AD). His second son, Aswawarman, married the draught of Sang Kudungga in Bakulapura [east Kalimantan] and grew Bakulapura into an established kingdom. The throne of Salakanagara itself was succeeded by Dewawarman’s first son. The royal family line persisted until 285 Saka (363 AD), the last king being Dewawarman VIII. |

It was additionally said that a son of Dewawarman VIII became the crown prince and, after his father’s death, became the king of Salakanagara, but his territory was under the command of Tarumanagara, a new kingdom established in 270 Saka (348 AD) by Jayasinghawarman who came from Salankayana and married the daughter of Dewawarman VIII, named Dewi Minawati.

It ought to be noted that a contemporary record in The Book of Later Han (後漢書) has been argued ever since the early twentieth century. In the Biography Series 76: South Barbarian - Southwest Province, it was written,

|

順帝永建六年, 日南徼外葉調遣使貢獻, 帝賜調便金印紫綬. |

|

In the 6th year of Yongjian Era during the reign of Emperor Shun (131 AD), [the king] Ye-bian (or Ye-tioa) from the exterior of the Vietnamese coast sent an envoy and submitted tributes. The emperor gave a gold stamp and a purple-ribbon medal [to Ye-bian]. |

In this line, Ye-bian (葉調) and Bian (便) were interpreted by G. Ferrand [64] as Jawadwipa (Skt. Yava-dvipa) and Warman (Skt. Varman, =Dewawarman), respectively. According to Tomonobu Kurihara [65], the first character (調) of Diao-bian (調便) could be regarded as a sort of “extraneous character”, so that the emperor gave the items to “the messenger”. In any case, if Ye-bian was the transliteration of Jawadwipa, then it is highly possible that the country was Salakanagara, because no established kingdom had existed in the early second century Java.

(3) The kings in the early Tarumanagara Period

As mentioned above, Tarumanagara was founded in 270 Saka (348 AD) by Jayasinghawarman who arrived from Salankayana and married the daughter of Dewawarman VIII of Salakanagara. His kingdom was initially a small village but grew to a significant size. The capital named Jayasinghapura is allegedly the origin of the present-day Jasinga, located about 45 km to the west of Bogor. [66] He was famous as “The Sage of the House of Ghomati (Sang Lumah ri Ghomati)”. He reigned until 304 Saka (382 AD).

|

Jayasinghawarman was succeeded by his son, Rajarsi Dharmayawarman. In addition to being a king, Dharmayawarman became the head of all religious teachers. He ceded the throne to his first son, Purnawarman, in 317 Saka (395AD) and lived in hermitage for two years before he died. Dharmayawarman was also known as “The Sage of the House of Candrabhaga (Sang Lumah ing Candrabhaga)”. Dharmayawarman’s younger brother, Nagawarman, became a high-commander and visited many foreign countries to establish and keep friendly relations. He became the ambassador in China and later in Swarnabhumi in Syangkanagari (Thailand). |

Purnawarman, whose name appeared in the stone inscriptions, was a great king who subjugated or conquered regional kings around West Java and expanded the territory of Tarumanagara to such an extent as judged from the locations of the discovered stone inscriptions (Figure 1). The Empress of Purnawarman was a princess of Swarnabhumi (Thailand), whereas other consorts were from Bakulapura (East Kalimantan) and Central Java. From the empress was born the crown prince named Wisnuwarman. The younger sister of Purnawarman, named Harinawarmandewi, became the wife of a rich man of Bharatanagari (India). He had a younger brother, Mandala-Minister Cakrawarman, who became the warlord and, after the throne was succeeded from Purnawarman to Wisnuwarman, attempted a coup d’état to become the King of Tarumanagara. This coup d’état must correspond to the record in The Book of Sung.

During his reign, Purnawarman made efforts to establish friendly relations with foreign countries, performed a number of riverworks, built two temples and edited many books, as will be mentioned below. His reign ended in 356 Saka (434 AD) and his throne was succeeded by his son, Wisnuwarman. He was called the Lord in “The Abode of Taruma River (Yang Bersemayam di Sungai Taruma)”.

Wisnuwarman, the fourth king of Tarumanagara, was the person who sent envoys at least twice to China. His seat was once seized by his uncle, Cakrawarman, but the treason was settled after a while. He married Princess Dewi Suklawati of the king of Indraprahasta (a subkingdom) who captured the rebel, as his first empress had already passed away. The incident will be mentioned below. He was succeeded by his son, Indrawarman, in 377 Saka (455 AD).

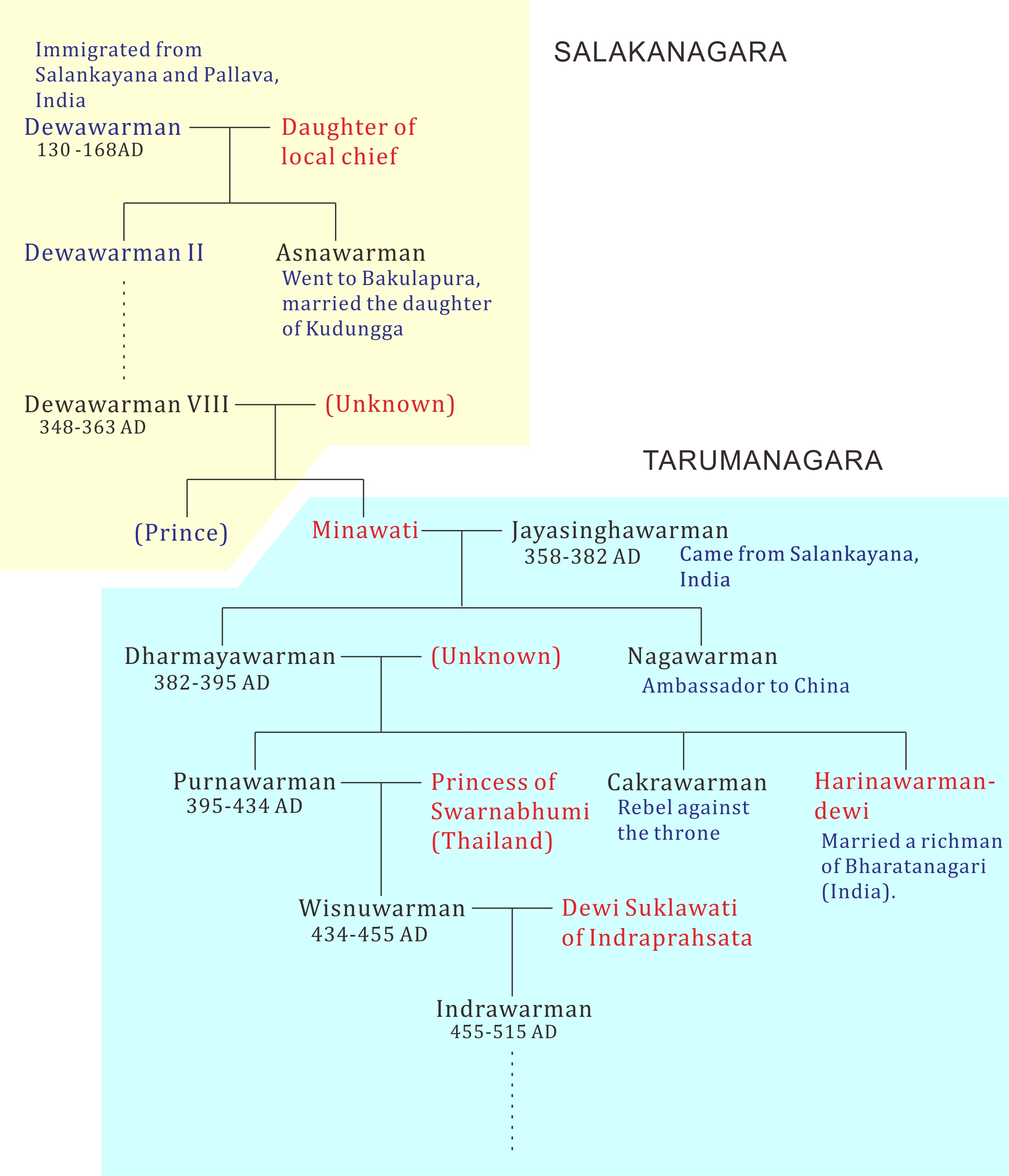

Figure 11 shows the genealogy of kings and their family members in Salakanagara and Tarumanagara covered by PPBJ I-1. The list of all kingdoms that had existed in West Java was given with reference also to other sources by Danasasmita.[67]

| Figure 11 The genealogy of kings and their family members in Salakanagara and Tarumanagara covered by PPBJ I-1. |

Now let us pick up some topics from the PPBJ 1-1 and discuss.

(4) Purnawarman’s personality and his capital

As a warlord, Purnawarman was portrayed in the PPBJ 1-1 as follows.

|

Since he was powerful and skilled in battle, he was feared by enemies as “The Tiger of Tarumanagara”. He was believed as the incarnation of Indra who was ready to attack his enemy. He was invincible. He always wore iron armour and rode on an elephant-back. He waged war against regional kings who did not accept his supremacy and always won. He also destroyed pirates who had infested around the Java Sea, namely in the sea battles in 321-325 Saka (399-403 AD), and made the water of the sea quite safe. .… |

With regard to the location of the capital, an interesting passage is found.

|

After Purnawarman became the king, he moved the capital to outside, where he made an inscription written by himself marked with the soles of his foot as a sign of his fame and power. |

Although “outside” in the first clause is implicit, the subsequent clause strongly suggests that the capital was “Aruteun” on the bank of Ciaruteun where the Prasasti Ciaruteun would have originally existed, though it was actually discovered in the riverbed and moved above the bluff in 1980s [68].

The above passage was followed by a line,

|

Purnawarman dwelled in the new palace with his empress and all his companions. |

This suggests that the large foundation stones that remained near the Prasasti Ciaruteun, mentioned above, were of use for the palace built by Purnawarman. The previous capital which Purnawarman moved from, is supposed to have been Jayasinghapura where his grandfather, Jayasinghawarman, had founded Tarumanagara.

In a later paragraph, the text said that

|

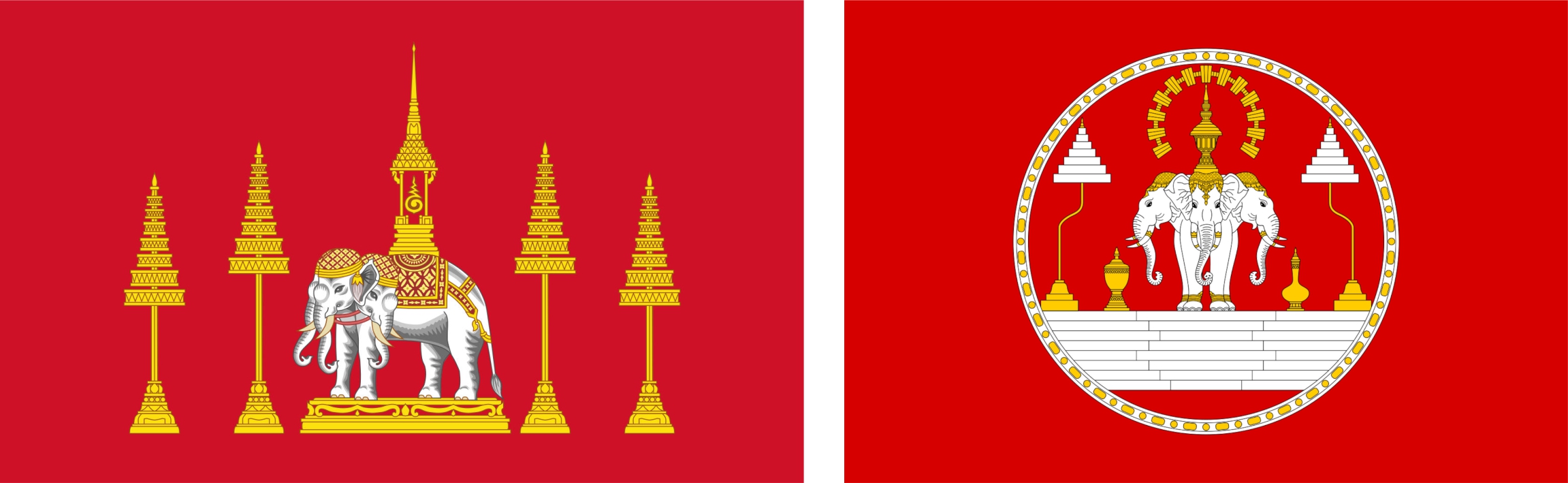

It was like a mandala. More than 12 kings from surrounding countries visited Tarumanagara. As for Purnawarman, he was in the palace in the capital city of Sundapura on the bank of Ghomati River. There, the flag of the Tarumanagara emblem, i.e., a symbol of a red lotus over the head of the elephant of Erawata (Airawata) [69], fluttering above the palace was seen. Navy ships and commercial boats were around the sea coast. |

Figure 12 shows the image of flags with the symbol of Airawata in the modern kingdoms of Siam and Laos.

| Figure 12 Royal standards of modern kingdoms with the symbol of Airawata. Left: Siam 1855-1891 (Rama IV), Right: Laos 1952-75. Both from: Wikimedia Commons. |

The above paragraph suggests that Purnawarman moved the capital again. The phrase, “the capital city of Sundapura on the bank of Ghomati River” is worth paying attention to. If the Prasasti Tugu in which the name of Gomati (Ghomati) River appeared was placed not far from the site of the riverwork, then the location of Sundapura would have been around the present-day Tanjung Priok, North Jakarta. The centre of Sundapura is supposed to have shifted due to the change of the coastline [70] and developed into Sunda Kelapa, the main port town of the Pajajaran Kingdom which was occupied and renamed as Jayakarta by Moslems in 1526-7 AD and subsequently became the nucleolus of the Dutch Batavia (Jakarta) constructed in 1621.

It is considered that Purnawarman had decided to build the new capital Sundapura at the coast of the bay for the sake of convenience of sea trading, as his kingdom had become solid and safe, whilst the previous capitals at Jayasinghapura and Aruteun, both located at the confluence of rivers in mountainous areas, were advantageous from the defensive point of view. For the environment of Aruteun, see Figure 8.

A passage in the PPBJ 1-1 said that Dharmayawarman tried hard to teach their religion (Hinduism) to the native inhabitants but many of those who adhered to believe in their ancestors were not easily taught and consequently the natives were divided into four caste groups, i.e., Bhrahmana, Kastryah, Waisya and Sudra, in which the lowest one was the majority. In another passage it was written that

|

In religious life Purnawarman worshiped Wisnu but there were people who worshiped Sangkara (Shiva) and Brahma. Also, there were a few Buddhism worshipers. Many indigenous people in the interior area still revered the spirit of their ancestors, retaining their old customs. |

These descriptions about the religious situation coincide with the aforementioned comment in A Record of the Buddhist Countries (佛國記) that “In this country, the paganism and Hinduism flourish but Buddhist dharma is trifling.”

The fact that Purnawarman worshiped Wisnu was proved in the epigraphs of Prasasti Ciaruteun which said that “the pair of footprints like unto Vishnu’s are Purnawarman’s”. In the PPBJ 1-1 it is also written that all participants in the banquet organised on the occasion of the ceremony of honour praised Purnawarman and his queen, as if they were God Wisnu, (the supreme lord in the Vaishnavism) and Goddess Laksmi (the goddess of wealth, fortune and prosperity), respectively.

Ever since ancient times the control of river water and the irrigation of the field have been big issues, namely in West Java, one of the most pluvial areas in Java Island or in the world.

With regard to the riverworks at Candrabhaga and Ghomati Rivers, it was described in the PPBJ 1-1 as follows.

|

Between the 8th of the dark-half of Phalguna [February] and the 13th of the bright-half of Caitra [March] in 339 Saka (417 AD), works to strengthen and beautify the banks along the Candrabhaga River and Ghomati River were performed. The work was carried out day and night by several thousand men and women for their respect for Maharaja. The inauguration ceremony and the thanks-giving ceremony were held by Purnawarman with 1000 cows, clothing and various delicacies. There the maharaja erected an inscribed stone inscription.

Then the Brahmins gave blessings to Sang Purnawarman. There, the maharaja made a stone inscription with an epigraph. Like he always did in other villages, he erected a statue of himself, an inscription of his footprint and an inscription of footprints of the holy elephant, Erawata (Regarding the relationship between the Hindu and Gregorian calendars, see Appendix 2). |

It is quite stunning that the dates of both starting and finishing of the work, as well as the number of immolated cows, exactly coincide with those written on the Prasasti Tugu. Then, the year of the work which was not inscribed on the Prasasti Tugu is considered to have been 339 Saka (417 AD). Now it is almost certain that “the king of kings” and “the Grand-father” in the Prasasti Tugu would have denoted Jayasinghawarman. “The Royal Sage” is still uncertain but the person would have been Dharmayawarman who was a devout religious teacher. The above description was preceded by a description that

|

As for the Candrabhaga River, since riverbank work was done some decades earlier by Jayasinghawarman, the Purnawarman’s grandfather, perfectly, beautifully and firmly. Purnawarman did this work for the second time. |

This corresponds to the first verse of the Tugu Inscription. Although the work period, 21 days seems to be very short to dig such a long canal of over 11 km, the work could have been done because the work at Candrabhaga River was just for repairing and also because the whole work was incessantly conducted day and night by concentrating such a great number of labourers, as much as several thousands. If one assumes that 5,000 labourers had engaged for the work of 11 km, the section of the bank per person was only 2.2 m in average.

Let us see the description of the riverwork at Sarasah River [71].

|

In 335 Saka (413 AD) a work to beautify and strengthen the banks of the Sarasah River (or Cimanuk River) was performed. Because Purnawarman was sick at the time, he was represented by the prime minister and some royal authorities to hold the sacred sacrifice [ceremony]. The tributes were 400 cows, 80 buffaloes, Brahman’s clothing, a Tarumanagara flag, 10 horses and a Wisnu statue. The impact of the work made the farmers happy because many marshlands became fertile. |

The statue is said of Wisnu’s in this case but supposed to have been the image of Purnawarman. The farmland created by riverworks is considered to have been provided with a drainage and irrigation system for agriculture. With respect to the Prasasti Tugu, it was concluded [72] that “the canals described were excavated in order to control the flooding of the river in the port area, rather than for the purpose of irrigation, as had been suggested by George Coedes [73] and others” but this was not the case at least at the Sarasah River.

In addition to the abovementioned river sites, Purnawarman conducted riverworks at three more sites. The name of the rivers and the year of the work were as follows.

|

Ghangga River in Indraprahasta [74] 332 Saka (410 AD), Cupu River in Cupunagara [75] 334 Saka (412 AD). Citarum [76] 341 Saka (419 AD). |

For the riverwork at these remote places in subkingdoms, Purnawarman sent a large number of labourers from the central kingdom. After the completion of the works, a thanks-giving ritual and a banquet were held as usual and monuments were erected.

The description that Purnawarman erected a statue of himself, as well as stone inscriptions, in multiple places (at the sites of Candrabhaga/ Ghomati Rivers, Sarasah River and other villages) is noteworthy. Although the two statues found in the Cibuaya Site were named as Arca Wisnu Cibuaya I and II, their photographs (Figure 13 (1) and (2)) give an impression that they were modelled after an armoured warlord, presumably Sang Purnawarman himself, who as aforementioned always wore iron armour. The age of the making of the two statues, assumed as the fifth or sixth century from the archaeologically aspect [77], is not much different from the time of Purnawarman’s reign, 317-356 Saka (395-434 AD). The Wisnu statues from Cibuaya, Figure 13 (1) and (2), are quite in contrast with the hallowed image of other rulers, e.g., the statue of King Airlangga of Kediri (3), who was also believed as the incarnation of Wisnu and that of King Kertarajasa (Raden Wijaya) of Majapahit (4), who was simulated to Harihara, a deity of half Shiva and half Vishnu.

| Figure 13 (1) and (2) Arca Wisnu Cibuaya I and II (photographed with permission at Museum Nasional Indonesia by. M. Iguchi, June 2019), (3) Statue of King Airlangga of Kediri (duplicated from https://alchetron.com/Airlangga), (4) Statue of King Kertarajasa (Raden Wijaya) of Majapahit found at Candi Sumberjati, Blitar (Duplicated from http://collectie.wereldculturen.nl/...) |

While Rajarsi (Dharmayawarman), the father of Purnawarman, retired and lived two years in hermitage before he died, Purnawarman made an inscription on a stone column, built a temple for Rajarsi on the bank of Candrabhaga River and another temple for Rajadhirajaghuru (Jayasinghawarman), the grandfather, on the bank of Ghomati River.

It was quite new at least to the present author that Purnawarman had constructed temples. From the above description, it is obvious that the temples on the bank of Candrabhaga and Ghomati Rivers had given the honourable names, “The Sage of the House of Candrabhaga” and “The Sage of the House of Ghomati”, for his father and grandfather, respectively. The year of the construction of the temples was not written but the year for the first one at Candrabhaga, at least, is assumed to have been between 317-319 Saka (395-397 AD).

These temples, however, are considered to be different from those discovered at the sites of Batujaya and Cibuaya located to the north of the present-day Karawan.

Besides the two temples at the banks of Candrabhaga and Ghomati Rivers, a passage which was grammatically inconsistent, but could be interpreted as follows, was found.

Dewawarman VIII of Salakanagara (reigned 270-285 Saka or 348-363 AD) built a temple (or temples) and installed the statues of Siwa and Wisnu,

This suggests that some temples had been built and statues, installed already in the third century during the Salakanagara Era.

(8) Diplomatic relations with China and other countries

In PPBJ 1-1, it was written that

| Purnawarman fostered equal, friendly relationship with China, Cambay in Bharatawarsa [India], Yawana [East India], Bakulapura [east Borneo], Syangka [Thailand], Palestine, Sibti [?], Arab Abbasid [78], Barusa [Kashmir], Cambay [west India], kingdoms in Central Java and East Java, and so on. Tarumanagara sent ambassadors to these friendly countries and vice versa. |

and that

| In 357 Saka (435 AD), Wisnuwarman sent his envoys to various countries, viz. China, Bharatanagari [India], Campanagari [Champa], Bakulapura [east Borneo], Dharmanagari [south Thailand], etc. Their mission was to inform to the kings of friendly countries that the king of Tarumanagara was changed to Wisnuwarman and that the friendship that had been nurtured would continue. |

According to The Book of Sung, the Aruteun Country sent envoys to Liu Sung China three times, for sure, in 430, 433, and 436 AD. Although no name was given for the first instance, the sender is considered to have been Purnawarman on account of the period of his reign, 395-434 AD, and the chief envoy, his uncle, Nagawarman.

The sender of envoys in 433 and 436 AD was apparently Wisnuwarman. In the former instance (430 AD), since Wisnuwarman was still the crown prince, it is probable that he wrote the letter with his signature on behalf of King Purnawarman. The year 436 AD in The Book of Sung is considered to correspond to the year 435 AD in the PPBJ 1-1, although one year difference lies between them.

The incident recorded in The Book of Sung that Wisnuwarman had once lost his position by a coup d’état may agree with the case written in PPBJ 1-1. As to the reason why the year is not found in the Chinese book, it could be probable that the relevant passage was a record from another letter received in 437 AD or in a later year.

(9) Coup d’état of Cakrawarman

Let us summarise the rather long description in the PPBJ 1-1 in short.

| Three years after the start of Wisnuwarman’s administration (359 Saka, 437 AD), an earthquake and a lunar eclipse occurred. They were bad omens. He was also plagued by nightmares and became troubled. One night when Wisnuwarman and his queen were in bed in the palace, someone stole into the room to assassinate the king but in vain, as he was found and captured by the guards. At first the intruder refused to say who had masterminded the assassination but later confessed that the task was given by Cakrawarman, an uncle of Wisnuwarman, or younger brother of Purnawarman. |

Although Cakrawarman had failed to assassinate Wisnuwarman, he is considered to have taken control of the country for a while as written in The Book of Sung.

| Several months later, four of the rebels were arrested but Cakrawarman and his high-ranked followers fled eastward into the forest at the edge of the Taruma River. When they arrived at the Cupu subkingdom, King Satyaguna immediately expelled Cakrawarman and his followers because the king remained loyal to the Purnawarman-Wisnuwarman line. Then, Cakrawarman and his followers hid in the forest in the southern part of Indraprahasta. Although Cakrawarman the Warlord had several high-commanders and a significant number of soldiers assembled from the territories under his influence, his armies were eventually defeated by the Indraprahasta’s troops after a heavy battle. After that, Wisnuwarman married the princes Dewi Suklawati of Indraprahasta, as his first empress had already died before. |

The scene of the battle was vividly written to tell us how the battle at that age was like. They had not only war-horses but also war-elephants. A lot of blood was shed in the battlefield and all houses around there were burnt. Cakrawarman and his commanders were killed during the battle.

(10) Books edited by Purnawarman

As an achievement of Purnawarman, it was mentioned that he composed various books, such as below, and many others.

|

• |

Nitipustaka Rājya Tarumanagara (Policybook of the King of Tarumanagara), |

|

• |

Nitipustaka ning Aksohini (Policybook of Battle Formation), |

|

• |

Nitipustaka Yuddhawarnana (Policybook of Warfare Description), |

|

• |

Nitipustaka Desantara i Bhumi Jawa Kulwan (Policybook Foreign Countries on the Soil of Java – One) |

|

• |

Pustaka Warmanwamsatilaka (Policybook of Warrior Society Tilaka*) |

|

• |

Pustaka Ghosanājñārājya (The book of Gosha-Anja-King?) |

| *) Marks placed on the forehead among Vaisya class people to show their sect. |

It is remarkable that many books were composed around the end of the fourth century to the early fifth century. As far as the present author knows, this fact has not been written in any publication other than PPBJ 1-1.

Among the list of materials used for the preparation of PPBJ 1-1 [79] are found books, Pustaka Tarumarajyaparwawarnana (The Book of .Descriptions about Old Taruma Kings) and Pustaka mengenai Warmanwamsatilaka i Bhumi Dwipantara (The Book about Warrior Society Tilaka on the Soil of Dwipantara) , the title of which look similar to those ofNitipustaka Rājya Tarumanagara and Pustaka Warmanwamsatilaka in the list of Purnawarman’s books. This suggests that the copies of Purnawarman’s books might have been available in the library of the Court of Cirebon in the beginning of the seventeenth century when the Wangsakerta Manuscripts were composed.

(11) The history of Bakulapura

As mentioned above, the Wangsakerta Manuscripts told of Bakulapura in Tanjungnagara [Kalimantan] which was established by Aswawarman, the second son of King Dewawarman of Salakanagara, who had moved there and married to the daughter of local chief, Kudungga. Since the names of Aswawarman and Kudungga appeared in the stone inscriptions called “Prasasti Mulawarman” (or Prasasti Kutai) [80] discovered in the lower basin of Mahakam River, Bakulapura was considered as the real name of Kutai Kingdom or Kutai Martapura Kingdom that was conventionally given after the Sultanate of Kutai Karta Negara in Martapura founded in the beginning of the fourteenth century. Figure 14 shows pictures of Prasasti Mulawarman.

| Figure 14 Two of the four Prasasti Mulawarman (photographed with permission at Museum Nasional Indonesia by. M. Iguchi, January 2019) |

Although the history of Bakulapura has no bearing on the subject of this book, let us en passanat discuss relevant passages in PPBJ 1-1 to verify the image of “Kutai Kingdom” obtained from the stone inscription.

With regard to the origin of the family, it was written that their ancestor arrived in Tanjungnagara [Kalimantan] from the Sungga dynasty in Magadha (in Bihar), India, when the dynasty was defeated by the Kusana [81] and fled scattered around the Archipelago. The village where their ancestor had settled was named Kuta (or Kutai). Kudungga was the son of Attwangga, and Attwangga, the son of Mitrongga Lughubhumi who was a contemporary of Dewawarman VI of Salakanagara (reigned 211-230 Saka/ 289-308 AD). The family in Kalimantan is said to have begun with Pusyamitra but the relationship between he and Mitrongga, whether the former was the father or grandfather of the latter, was not clear, as unfortunately the descriptions about Bakulapura did not give the year of the kings’ coronation and abdication, unlike those about Salakanagara and Tarumanagara. The kinship between Aswawarman and Kudungga was not clear from the Prasasti Mulawarman, but it is now evident that the former was not the real son but son-in-law of the latter, originally the second son of King Dewawarman of Salakanagara of West Java who married the daughter of the latter.

During the reign of Aswawarman Bakulapura became a great country, where people lived prosperously and peacefully. Thereby Aswawarman was regarded as the founder of the Bakulapura kingdom. After the throne was succeeded by Mulawarman, Bakulapura grew further into a bigger and more powerful country, so that kings in neighbouring countries were subjected to Bakulapura’s authority. With Tarumanagara, Bakulapura had maintained a good relationship. About the decline of the kingdom, no description is found in the Wangsakerta Manuscripts.

It should be remarked that a past view that “Kudungga is not a Sanskrit word, and seems to point to the Indonesian origin of the family” [82] seems to be inappropriate now with reference to the information from the Wangsakerta Manuscripts. The fact that the Bakulapura family worshiped Hinduism was already evident from the Mulawarman Inscriptions.

Concluding Remarks

|

(1) |

The previous assumption by the present author that the unidentified country, 呵羅單, recorded in The Book of Sung was the transliteration of Aruteun and that Aruteun Country was the alternative name of Tarumanagara represented by the name of the capital has been ascertained with detailed investigation of the Chinese text and reference to the Wangsakerta Manuscripts, viz. PPBJ 1-1. In particular, the dispatching of envoys to China by King Wisnuwarman (毗沙跋摩) has been confirmed by the corresponding descriptions in PPBJ 1-1. It has also been learnt that friendly relationships were established earlier during the reign of King Purnawarman and ambassadors were exchanged not only with China but also many other countries. |

|

(2) |

The origin of the family of Tarumanagara and Bakulapura (Kutai), which was formerly assumed as India from the Sanskrit script of stone inscriptions, is now clear and the kinship between the families of Salakanagara, Tarumanagara and Bakulapura has been learnt from PPBJ. |

|

(3) |

Descriptions corresponding to those in the epigraphs on the stone inscriptions of Tarumanagara Era were also found in PPBJ 1-1. It is especially remarkable that the year of riverworks at Candrabhaga and Ghomati Rivers which was not written in Prasasti Tugu was specified in PPBJ 1-1 and that “The king of kings” and “the Grand-father” in the same stone inscription were identified as Jayasinghawarman, the founder of Tarumanagara. According to PPBJ 1-1, Purnawarman conducted riverworks not only at the above two rivers but also at many other rivers in the territory of Tarumanagara and founded many cities including Sundapura, the nucleus of the later-time Sunda Kelapa, Jayakarta, Batavia and Jakarta. |

| (4) | The fact that Purnawarman had composed many books and that they would have remained in the court of Cirebon when the Wangsakerta Manuscripts were written is new to us, not found in other references. |

| (5) | The Arca Cibuaya I and II discovered at the Cibuaya Site and possibly similar ones erected at other places are considered to have been modelled after the armoured Sang Purnawarman, although this is no more than an imagination. |

Nevertheless, with respect to the location of Candrabhaga and Ghomati Rivers, whichever of the followings is right, remains still unclear.

|

(a) |

Around the present-day North Jakarta, where the Prasasti Tugu was unearthed, |

|

(b) |

The present-day Ciaruteun Ilir Village, where stone monuments, Prasasti Ciaruteun and Prasasti Kebon Kopi, were found, |

|

(c) |

Elsewhere. |

(“*” denotes Japanese and Chinese references)

[1] . Pararaton, a biography and genealogy of Ken Arok who founded the Singasari Kingdom, allegedly written in 1481-1600 by an anonymous author. The copy was found in Bali by J. L Brandes in 1890th (J. L. Brandes, Pararaton (Ken Arok): of het Boek der Koningen van Tumapĕl en van Majapahit , Bataviaasch Genootschap, 1920). Although in some books are written that Pararaton was found earlier by Stanford Raffles and published in his The History of Java (1817), it does not seem to be correct. Full English translation: I. Gusti Putu Phalgunadi, The Pararaton: A Study of the Southeast Asian Chronicle, Sundeep Prakashan, New Delhi, India, 1996.